Kaspar Hauser, Part One: Foundling

With this installment, we’ll begin a series exploring one of the most famous historical mysteries, one which gripped all of Europe with speculation and obsession for years and even today brings new fascination and astonishment to those who discover it. The story involves a mysterious character of unknown origins, suspicions of dynastic chicanery, accusations of imposture, and of course, tales of shadowy assassins. This is Kaspar Hauser, Part One: Foundling.

*

Even in the early nineteenth century, legends about wild foundlings were not new. The feral child was a concept that had long captured the interest of the public. Particularly prevalent was the concept of a lost or abandoned child who survived in the wilderness with help of animal benefactors. Tales of human children who were raised by wolves go all the way back to the Middle Ages. In the early 13th century, French chronicler Jacque de Vitry describes a she-wolf stealing and suckling human children and striking them with a paw when they tried to walk upright, teaching them, essentially, the posture of beasts. And in Caesarius of Heisterbach’s Dialogus Miraculorum, we hear of another youth kidnapped away from civilization and fostered by wolves, taught to go about on hands and feet—quadripedally, as it were—while howling wolfishly.

Then the 14th century brought stories of Hessian wolf children. In 1304, tales of a boy snatched from Hesse and living in primeval splendor, laying about the bases and trees and sharing in his wolf pack’s daily catch of game. It is said they ingeniously created crude shelter in winter for the youth, who had no pelt to protect him from the elements. Upon his return to human society, all were quite astonished by the facility with which he leapt and bounded upon all fours, and he proved splendid entertainment in the court of the Hessian prince. Nevertheless, his keepers felt it more seemly that the boy walk erect, which they accomplished by forcibly binding him to a piece of straight wood. The fame of this Wild Boy of Hesse surely colored the motived of hunters some 40 years later, in the Hessian region of Wetterau, when they reportedly discovered another boy who had been living with wolves for 12 years. Again, this feral Hessian child was reintegrated into human society, perhaps more successfully as he lived a recorded 80 years. Indeed these tales of feral children, which may today seem a bit too fabulous to be real, nevertheless inspired Carl Linnaeus, originator of the zoological classification system of binomial nomenclature, to indicate a separate sub-category of humanity designated Homo ferus.

And these stories of feral foundlings were fresh in the mind for Europeans in the early nineteenth century. In 1725, a naked, hairy, skittish child of about 12 was discovered in northern Germany, subsisting on grass and leaves in a forest near Hamelin. Unable to speak when he was captured, he was at first kept in a correctional facility before being brought to the court of King George at Herrenhausen as entertainment. He could not stomach bread, and the food he did take—vegetables and rare meat—he devoured messily, with no concept of manners. Thereafter taken to London, he became the toast of the town, serving as the philosophical inspiration of such luminaries as Jonathan Swift and Daniel Defoe and ending up as a kept creature of the Princess of Wales. Given the most respected educators, the Wild Boy of Hamelin, called Peter, made no progress in his letters, causing his tutors eventually to give up their efforts as pointless. Peter was eventually and quite literally put out to pasture, sent to live the rest of his ignominious days as a farmhand. He never learned to speak, but taking a final lesson from civilized people, he did learn to drink gin.

Peter the Wild Boy, via Wikimedia Commons

These stories of feral children, prominent in the zeitgeist of the 19th century, were not always to be trusted, however. Near the dawn of the 1800s, in southern France, some men exploring a forest found a wild boy who would come to be known as “Victor of Aveyron.” He is described as 11 or 12, his naked body dirty and heavily scarred. Much like Peter, Victor fled when approached but was treed by his pursuers and captured. In a neighboring village, where his captors gave him into the care of a widow, there were reports of having seen the child living in the woods for years. After escaping from the widow’s care, and being recaptured, Victor was sent to Paris to be analyzed as an untainted and pure example of human intellect in its most nascent state. Most doctors who examined him, however, agreed that he was not a feral child but rather a child with cognitive disabilities who had been abandoned by his parents. Indeed, this suggestion appears to offer a convincing explanation for Peter the Wild Boy of Hamelin as well, for modern experts suggest Peter may have suffered from the chromosomal condition known as Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. This idea actually tends to cast doubt on any stories of wild foundlings who showed a lack of intellectual development or failed to respond well to education in that, sadly, they may have been disabled youth callously deserted in the wilderness.

Thus the popularity of wild foundling narratives persisted in the early 19th century, even if it was occasionally dampened by suspicions that the child was not a true savage. It was in this cultural milieu that, on May 26th, 1828, a strange and awkward youth trudged into Nuremburg in what was then the Kingdom of Bavaria. As it was Whitsuntide, a religious holiday commemorating the Pentecost, few people were out roaming the streets, and the tottering figure drew the attention of a shoemaker who stood outside his home enjoying the day. The shoemaker watched as the boy, who looked about 16 years old and seemed healthy enough at a distance, with a strong and thickset frame, came wobbling toward him. Then the shoemaker noticed his unsteady gait, his ragged peasant’s clothes, his boots that were far too small for his feet, and, as the boy came nearer, the blank expression of the blue eyes beneath his wide-brimmed hat. The boy gave him an uncivilized greeting in an unfamiliar country dialect and indicated abruptly and vaguely his interest in finding New Gate Street. Despite the boy’s simple and broken communication, the kind citizen understood and led him across the Pegnitz River. It was then that the boy, who was clearly struggling to walk in a coordinated manner, produced a sealed envelope from his coat. Examining it, the shoemaker saw that it was addressed rather specifically to the captain of a light horse regiment, prompting the shoemaker to suggest that the boy did not want New Gate Street but rather the New Gate Tower itself, where the guardroom was located. The uncouth boy exclaimed that this tower must be a new structure, to which the shoemaker responded with confusion, for the New Gate was very old indeed. Curious, he asked where the boy had come from and the boy replied that he came from Regensburg. This was to be the only time that this remarkable and enigmatic foundling would ever name a place of origin, and indeed, when the shoemaker asked for news from Regensburg, the boy offered none, as if he knew little of the place from which he came.

Kaspar Hauser, via Wikimedia Commons

The shoemaker returned home once he had seen the boy to guardroom, where the boy removed his wide-brimmed hat and handed the letter to a corporal on duty. The corporal, for his part merely handed the letter back, telling the boy the location of the home of the addressee, the Captain of the Fourth Squadron of the Sixth Regiment of Light Horse. The boy left then, and surprisingly, without any guidance that was recorded, he managed to find his way to the captain’s house, where he gave the letter to a servant and announced in his unsophisticated way that he wanted to be a trooper, like his father before him. He knew not where he had come from, he said now, but it had been a long journey to Nuremberg, during which he had been forced to march ceaselessly. The servant showed him to the stable, where he would be permitted to wait for the captain, and before falling into the deep slumber of true exhaustion, he shared some details about himself with the captain’s man. Upon seeing the horses in the stable, he said, “There were five of those where I was before,” and he told the servant that he had learned his letters in this ambiguous former abode, traveling daily across borderlands to receive schooling. The boy was given beer to drink and meat to sustain him, but this did not please him, for he shrank from the victuals with revulsion. He was indeed extremely hungry and thirsty, but it turned out the only nourishment he could stomach were bread and water.

Eventually, the Captain of the Fourth Squadron arrived and went to the stable to see his visitor. The boy greeted him with delight, reaching out to fondle the shiny ornaments of his uniform and grasping at the sword on his hip, saying innocently, “I want to be such a one!” The captain asked the boy’s name, and the boy said, “I do not know, Your Honor.” Doffing his wide-brimmed hat then, he made reference to a mysterious foster father who had taught him the etiquette of removing his hat in the presence of others, and to address them with the honorific he had used in responding to the captain. The captain took the letter the boy offered and read the following:

From the Bavarian Frontier;

the place is not named.

1828.

High well-born Captain!

I send to you a boy, who might, as he wishes, serve faithfully the King; the boy was left with me, 1812, the 7th of October, and I am a poor day-labourer, with ten children, and have enough to do to take care of them, and his mother left the child with me to bring him up, but I have not been able to speak to her and I did not mention to the Justice that the child was left with me. I thought that I must consider him as a son, and have brought him up like a Christian; and have not, since 1812, let him go a step from the house, in order that nobody might know where he was brought up, and he himself does not know how my house is called, nor what the place is called; you may ask him, but he cannot mention it. I have already taught him to read and write: he can write my hand-writing like myself; and when we ask him what he will become, he says, he will be a light horseman, as his father was. If he had parents, which he has not, he would have been a learned lad. You need only shew him any thing, he can do it at once.

I have brought him only as far as Neumark, from thence he must go to you. I have said to him, that when he is once a soldier I will come immediately and visit him, otherwise it would cost me my neck.

Best of Captains, you need not trouble him at all, he does not know the place where I am, I brought him away during the night, he does not know the way home.

I am your obedient; I do not make my name known as I could be punished.

And he has not a farthing of money with him, because I have none myself, if you do not keep him, you may kill him, or hang up in the chimney.

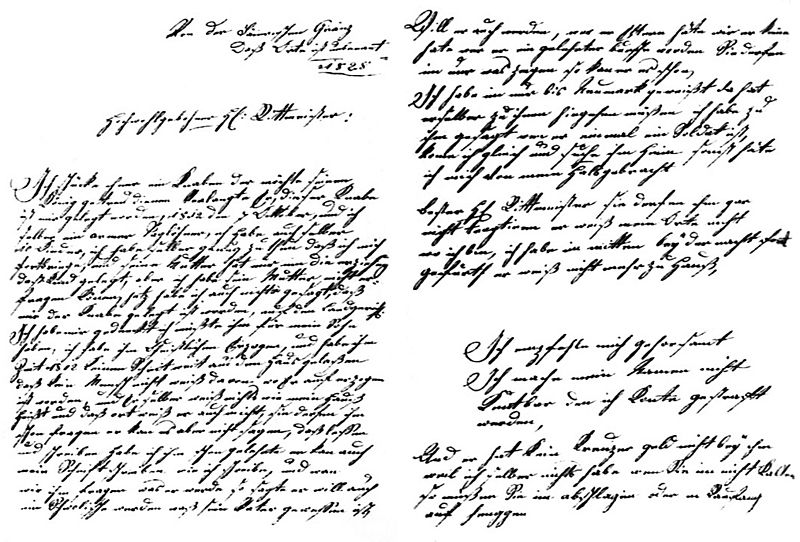

Old facsimile of Kaspar's Letter, via Wikimedia Commons

Enclosed with this letter was a note on a scrap of paper, seemingly written in the same hand and with the same ink but in Latin. This note read:

The child is already christened, is called Kaspar; you must yourself give him a surname, and bring him up; his father was a light horseman; when he is seventeen years old, send him to Nuremberg, to the 6th regiment of light horse, in which his father also served. I beg you to bring him up till seventeen years old. He was born on the 30th of April, 1812. I am a poor girl; I cannot support the child; his father is dead.

Understandably, the Captain was at a loss as to what he should do with the strange boy named Kaspar. Eventually he decided that it was a police matter and took the child to the police station, where the timid Kaspar was subjected to a rough interrogation. When asked his name, he wrote down “Kaspar Hauser,” which seems like it might have been a name used to mock the boy, if the letter’s indication that he had never been let out of the house is to be believed, as “hauser” could be construed to mean a person who is never allowed outdoors, or a “house-er.” When asked where he was from, Kaspar answered, “I dare not say…because I do not know.” Indeed, he replied to most questions with similar, repetitive answers, pleading ignorance and again reminding everyone that he wanted to follow his father’s footsteps as a soldier. One police officer threatened to abandon him in the woods if he didn’t admit where he was from, and Kaspar panicked and wept like a child: “Not the forest,” he pleaded, “not the forest!” Despite his apparent distress, Kaspar offered them no further insight into his origins, and he was thereafter locked up as a vagrant in the watchtower of the imperial castle.

Before imprisoning him, the police searched his person for some hints to his identity. His trousers appeared designed for riding horses, and his ragged jacket and handkerchief both had been embroidered with the letter “K.” In his pockets, he carried some interesting items: a key, a rosary, a prayer book, some religious tracts…and a small envelope containing a bit of gold dust! So much for the letter’s assurance that searching him would be pointless as he carried no money. And poignantly, considering the narrative offered by the letter and the tale that this “Hauser” was soon to tell, one of the tracts on his person bore the title, “Art of Recovering Lost Time and Ill Spent Years.”

During his confinement in the tower, physicians examined him, and they determined his facial expression to be remarkably listless, comparing him to a caged and dispirited animal. His hands and feet, they noted, were surpassingly soft, betraying a life of little physical hardship, and indeed, his feet, which had been stuffed into boots far too small for him, were covered in blisters, as if they had gone long unused. Otherwise, he seemed hale enough, strong and well-fed, despite his finicky tastes. He refused to take anything but black bread and water, and this was not pickiness but rather an inability to digest anything else, for when anyone slipped any other fluids into his water—coffee or alcohol—or when they concealed meat inside the bread he ate, Kaspar suffered severe physical reactions: headaches, vomiting and diarrhea. Indeed, when word spread about the Wild Boy being kept in the tower, a great many curious visitors came to meet Kaspar, and some of these were not the kindest of callers. Some, having heard of his timidity and his violent reactions to food, would brandish swords before him and laugh at his fear or slip him food or drink that would disagree with him and delight in his ensuing sickness.

Judge Anselm von Feuerbach, via Wikimedia Commons

Others, however, were kind to him, offering him coins and children’s toys, his most prized being a hobby horse. His reaction to these gifts evinced an unusual childishness for his age. He appeared to love anything shiny, and when coins were held out to him and then snatched away, he bawled like an infant. When first his cell had been lit by candle, he reached innocently to touch the flame and recoiled in surprise at the pain of being burned. When presented with his own image in a mirror, like a baby, he reached out to touch the image and circled the looking glass in an attempt to find the child on the other side. These convincing reactions caused many who visited him to believe his story utterly, including the turnkey at the tower, who brought his two-year-old to the tower and watched as Kaspar somewhat ridiculously flinched and withdrew, afraid that the toddler would strike him. Another visitor, Paul Johann Anselm von Feuerbach, a judge of the appeals court, took a great interest in Kaspar after he visited the tower and offered Kaspar two coins, one a shiny coin of lesser value and another a dirty coin of higher value, and was surprised when Kaspar preferred the less valuable one simply because of its luster, even after the Judge explained that it was worth far less. Judge Feuerbach would write a book about Kaspar Hauser that he would publish in 1832, and from the very start, he was certain that the Foundling of Nuremberg was an honest and innocent child, and more than that, as the boy’s vocabulary and ability to communicate grew at leaps and bounds, he began to suspect that Kaspar was a child of great potential and perhaps magnificent origins. When Kaspar finally imparted the story of his origins, the Judge’s suspicions only increased.

Kaspar told of a lifetime of imprisonment in a far smaller cell than he currently enjoyed at the castle tower. The room that was the only world he knew for all his life had been of such small dimensions that most of his years he had spent on his knees or seated. This dungeon had two small windows, but these were kept shuttered or boarded up, so that Kaspar had known only shadow and pitch darkness. The trousers he found himself always wearing had no seat so that he could move his bowels without disrobing, and this he did in a hole in the floor of his miserable cell. His only companions in that place were hobby horses—hence his favor for such toys—and he never saw his captors. Whenever he woke, there was bread and water for him, and occasionally, after noticing his water had a strange taste, he grew drowsy, and upon waking found his nails pared and his clothing changed. This was the nature of his young life, day upon week upon month upon year, until such time as his captor decided he must learn to speak and write and walk like a man. This was somehow, improbably, accomplished in the darkness of his cell by a still unseen jailer who spoke to him until Kaspar could repeat some useful sentences and reached inside to guide Kaspar’s hand in writing his name. Only then had Kaspar been taken outside and taught to take a few wobbly steps before being carted off to Nuremberg and dumped inside the city gates with his letter of introduction.

The story became a sensation in Nuremberg. The very fact that anyone could treat a child so heartlessly, like an animal, created justified outrage, as such terrible tales of child neglect and abuse have tended rightly to do ever since. With the general goodwill of the city extended to him, Kaspar Hauser became an object of pity and love, adopted by Nuremberg as the city’s own child, with many swearing that he would never want for care or comfort. Charitable donations poured in, such that Kaspar Hauser would no longer need to worry about food, clothing, or lodging and would be able to receive a respectable education.

Kaspar's imprisonment, from a contemporary engraving, via LiFo

Enter Georg Friedrich Daumer, retired schoolmaster. Like so many others, Daumer had taken an interest in Kaspar and offered not only to put up the boy in the house he shared with his mother and sister but also to educate him. Thus a new chapter of Kaspar Hauser’s life began, and Kaspar took up residence with the Daumers. During this new life, he made excellent headway in learning to read and write as well as in his other studies, and true to his love of horses and his dreams of becoming an equestrian, he took easily to horsemanship, a fact that Daumer attributed to his having sat for most of his life, creating a bottom perfect for the saddle.

Daumer, however, was motivated by other interests beyond charity in his stewardship of Kaspar Hauser. Considering himself a man of science, he saw in Kaspar Hauser a perfect opportunity to study a pure example of humanity, a blank slate of a man who had not yet been corrupted by society, this being a common attraction for those who studied feral children. Indeed, Daumer was interested in the burgeoning alternative medicine system known as homeopathy, which proposed natural, herbal remedies administered in tinctures diluted to such a degree as to seem wholly ineffective. Daumer and an associate homeopath, Dr. Paul Sigmund Preu, performed unending experiments on Kaspar, spiking Kaspar’s water with a variety of herbal concoctions. To their delight, their experiments produced gas, vomit, and diarrhea in their subject, even in extremely diluted form, which they believed to be hard evidence proving the tenets of homeopathy.

Moreover, Daumer and Preu attributed preternatural abilities to Kaspar, claiming that they observed in him the ability to hear and smell at greater distances than most humans and the faculty of seeing even in pitch black darkness. And perhaps the most astonishing of their findings, they claimed that Kaspar was somehow sensitive to magnetic fields, able to find hidden metal objects like a pig sniffing out truffles. Daumer also observed that Kaspar felt some unusual sensations when touching animals and appeared to have some kind of supernatural connection to animals, feeling a kind of sympathetic agitation when animals he was near became distressed or excited. This, Daumer believed, was an example of “animal magnetism,” a concept proposed by mesmerists.

These, of course, seem to be dubious claims, and indeed, when one looks into Daumer’s background, one finds a great deal of eccentricity. Daumer adhered to a variety of pseudo-scientific ideas, including spiritualism and alternative history, some of which was decidedly anti-Semitic. For example, he believed that ancient Jews cannibalized their firstborn in sacrificial rites, and in a less anti-Semitic and more just absurd belief, he traced the path of Jews escaping Egypt all the way across the Asian continent to the New World, suggesting that the parting of the seas was actually a crossing of the Bering Strait, which promptly melted behind them to drown Pharaoh’s armies.

Georg Friedrich Daumer, via Wikimedia Commons

Nevertheless, Daumer did appear to care for Kaspar, for his well-being and education. While under Daumer’s care, much of the city and the world beyond, thinking him well taken care of, lost interest in the story, but not Judge Feuerbach, who had begun to formulate outlandish theories about Kaspar’s origins. The fact that Kaspar showed such a natural predilection toward learning and that, apparently, so much effort had been made to conceal his existence as a child led Feuerbach and many others to hypothesize that Kaspar was actually the descendant of a royal family, and perhaps the heir to a throne, kidnapped and hidden away in order to manipulate a dynasty. Others, however, would point out the inconsistencies in Kaspar’s story to suggest he was a liar and a fraud, for had he not said there were horses where he was from? Had he not been wearing riding breeches? Would not this explain how he took so well to horseback riding? And had he not said that he used to cross borders to go to school? This certainly didn’t jibe with his story of imprisonment in the dark and would certainly help to explain how he was learning so easily, for could he not have simply been pretending to learn things he already knew well?

These are the questions that have lasted from then even until today, when we look back on what we know of Kaspar Hauser and try to come to some conclusion that satisfies. But at this historical distance, we are like a child groping about in the dark, blind to what may be a simple and obvious truth.

*

Thank you for reading Historical Blindness. Join us again in two weeks when we’ll look at another case of a foundling that was taken by many to be royalty, an incredible case of charlatanism and staggering credulity that easily may have colored the public’s perceptions of the Wild Boy of Bavaria. Then we’ll be back in four weeks for the conclusion of this dumbfounding tale: Kaspar Hauser, Part Two—Princeling.

In addition to the work of Judge Anselm von Feuerbach, to which I’ve linked throughout as source material, I am indebted to the work of Dr. Jan Bondeson, whose book, The Great Pretenders: The True Stories behind Famous Historical Mysteries, has been an indispensable resource in composing this installment.

Tell people about the blog! Let them know how much you like it and why you think they’ll like it too. Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter, and you can share and retweet our posts there to tell even more people about us. And you can directly support the blog and podcast by purchasing my book, Manuscript Found!, on Amazon, a historical novel about the dubious origins of Mormonism and a Masonic murder mystery that helped shape American party politics.

Until next time... keep your eyes wide...