Blind Spot: The Oberfohren Memorandum and the Ernst Confession

Thank you for reading Historical Blindness. We are now a fortnightly blog, alternating between our full-length installments and shorter bonus posts every two weeks. These Blind Spots serve as companion pieces, telling a separate but similar tale or further exploring the last installment's story by relating an aspect of it we didn’t have time to include. In this Blind Spot, we’ll do the latter, so if you haven’t read the last installment, Firebrand in the Reichstag!, please go back and do so before enjoying this Blind Spot.

*

The story of the Reichstag Fire and the legend of a conspiracy behind it is so far reaching and epic that we did not have time in our already oversized post on the topic to include some of the most interesting passages. Therefore, I proudly present here the stories of two men’s untimely deaths and the disturbing documents that cropped up afterward, linking them to the Reichstag Fire and suggesting a conspiracy to murder and silence them. This is an account of the Oberfohren Memorandum and the Ernst Confession.

Dr. Ernst Oberfohren, via Wikipedia

On April 26th, 1933, two months after the burning of the Reichstag and still several months before the publication of the Brown Book and the convening of the farcical London Counter-Trial, the first stirrings of the conspiracy theory that would come to dominate the Reichstag Fire narrative appeared. In a couple articles in an English newspaper, the Manchester Guardian, it was revealed that a manuscript was furtively circulating in Germany, written by a high-ranking official of the Nationalist party, which had until the recent seizure of power been allied with the Nazis, and it purported to tell the true story of the Reichstag arson, suggesting here for the first time in print that the Nazis themselves entered the Reichstag via the underground passage from Göring’s residence, setting the fire to create a Bolshevik scare and thereafter capitalize on the ensuing anarchy to establish a dictatorship. Appearing aghast at such an allegation in the foreign press, the German Legation in London lodged a protest against “so monstrous a vilification,” but soon enough the newspaper’s source surfaced, a memorandum attributed to former parliamentary leader of the German-National People’s Party, Dr. Ernst Oberfohren, recently deceased after an ostensible suicide on May 7th. According to the memorandum’s anonymous introduction, however, Oberfohren’s home had been raided by Brown Shirts, or soldiers of the S.A., the Nazi’s private army, who after finding a copy of the memo, allowed him to commit suicide as the only alternative to a much worse fate.

The Oberfohren Memorandum made a number of accusations, including that, during the raid of the Communist Party headquarters previous to the fire, Brown Shirts had planted guns and documents intended to create the false impression that a workers’ uprising was afoot. When this failed to elicit the uproar they desired, according to the memo, they instead resorted to the arson of the Reichstag. The act was accomplished by Brown Shirts, entering via the tunnel, and leaving behind their “creature,” Marinus van der Lubbe. And in the uproar that ensued, the Nazis planned an armed overthrow of the government in the early days of March that had only just been thwarted by unfavorable circumstances. As can be discerned from the memorandum, Dr. Oberfohren despaired over what the future might hold, and when Hitler’s swastika might usurp the place of the iron cross atop German flagpoles. Thus he had circulated the manuscript, which made its way outside of Germany and presaged the narrative of the Brown Book to come, as well as much historiography for the next three decades.

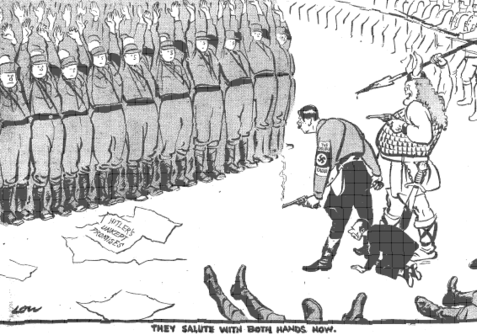

1934 British cartoon satirizing the Night of the Long Knives, via Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias

Oberfohren was not alone in having the circumstances surrounding his death questioned and having attributed to him a document that incriminated the Nazis in the Reichstag Fire affair. Around a year after the release of the Oberfohren Memorandum, and half a year after Marinus van der Lubbe had been decapitated for his crime, came the dark and bloody Night of the Long Knives. The popular name for this event hearkens back to the medieval legends of King Arthur, and specifically the murder of unarmed britons by Saxon mercenaries at a banquet in what was called the Treachery of the Long Knives, and indeed the name’s conjuring of violent betrayal is apt, for the Night of the Long Knives, or the Röhm Putsch as Germans know it, was a bloody purge of Hitler’s own private army, the S.A. You see, when Hitler rose to power, he gave a lot of lip service to socialist ideology—hence the National Socialist German Workers’ Party—but having seized power and now aiming for further military domination beyond Germany’s borders, he would need to focus on industry and feared that elements of his Brown Shirt army who had believed his talk of workers’ rights would turn on him and prove to be an impediment. Furthermore, some leaders of the Brown Shirts, including founder Ernst Röhm, his deputy Edmund Heines and Berlin chief Karl Ernst, were known homosexuals—remember that van der Lubbe was depicted in the Brown Book as a homosexual prostitute in service to Röhm—so some among the Nazi leadership, including Göring, found their lifestyle as well as their politics distasteful. These were all reasons enough to turn on some of their staunchest supporters; therefore, on the 30th of June, they launched operation Hummingbird with the force of the other wing of their private army, the S.S. or Black Shirts. That day they arrested and executed numerous Brown Shirt leaders—including Röhm, Heines and Ernst—along with various political figures they deemed problematic, all under the guise of removing immoral elements from their ranks.

Imagine that: a demagogue rouses the downtrodden and resentful to gain power and then promptly betrays their interests. What a surprise…

After the purge, another document surfaced, this one purporting to be a confession penned by recently executed Karl Ernst, in which he admits to conspiring with Nazi and S.A. leaders in firing the Reichstag. Foreseeing the betrayal of Göring and Goebbels, Ernst had written the confession as a safeguard, to keep himself from being assassinated lest it be released upon his death (a gambit that apparently had not succeeded). The Ernst Confession described the entire affair, even from its earliest planning stages, when Göring and Goebbels had felt compelled to scrap a different plan involving a supposedly Communist assassination attempt on Hitler in Breslau. After considering other targets, they settled on the Reichstag, since then they could appear as “champions of parliamentarianism.” Thinking at first they would hide within until it was empty, they feared being seen and recognized by Communists. According to the confession, it was Ernst himself who came up with the idea of using the underground tunnel, and while inspecting it and hiding their incendiary material, they had almost been caught by the watchman. In this version of events, one of the conspirators had met Marinus van der Lubbe, and thinking him a likely fellow of whom they “should be able to make good use,” convinced him that setting fire to the Reichstag was a grand idea. Thus, as Ernst and the real arsonists were escaping back through the tunnel, having set numerous fires in the Session Chamber, van der Lubbe’s handler was to see him to the Reichstag and ensure he broke into the restaurant to “blunder about conspicuously,” thinking himself the sole arsonist. This is the picture the Ernst Confession paints: calculated manipulation of the political situation, perfect execution of a false flag incident, and utter vindication of the allegations in the Oberfohren Memorandum and the Brown Book.

Karl Ernst, via Wikimedia Commons

Needless to say, this document did not look good for Hitler and his party, but at this point, the Nazis were beyond redemption in the eyes of the foreign press, and their power in Germany was quickly becoming impossible to challenge. By the end of the summer, President Hindenburg died and Hitler took for himself the position of Führer of Germany, the title meaning vaguely a guide but the role essentially that of a supreme despot. And thenceforth, history marched on in goosestep.

Not until the publication of Fritz Tobias’s groundbreaking work in Der Spiegel did anyone bother to examine the credibility of these documents, the Oberfohren Memorandum and the Ernst Confession. Rather than take them at face value, Tobias attempted to determine the true authors of the documents and to either corroborate or refute their contents. He began by examining the last days of Dr. Oberfohren and his suicide.

As Tobias shows, Oberfohren, a former professor of political science who had taken a position as chairman of the Nationalist deputies in the parliament under party leader Alfred Hugenberg, was increasingly disillusioned with his party, having openly opposed the Nationalists’ decision to give Hitler the chancellorship in an effort to forge a joint majority with the Nazis. Indeed, he had composed some pamphlets attacking Hugenberg and had been found out as the author, resulting in his resignation. Tobias demonstrates that because of his opposition to the Nationalist alliance with the Nazis, he would not have been privy to any secret operations at the time of the fire. Indeed, his suicide appears not to have been compelled by Nazi Storm Troopers but rather precipitated by a combination of emotions: guilt over betraying his party and depression over the direction his country’s government was taking. Visitors during his final days later testified to his hopelessness and, as his own wife put it, his “black despair” over the inevitable rise of a Nazi dictatorship and his powerlessness to oppose it. In fact, his suicide letter is actually addressed to Hugenberg as an apology, describing the “superhuman agonies” he was suffering and bemoaning the damage he had done to the Nationalists.

Thereafter, Tobias addresses the major theses of the memorandum, offering evidence that firearms and revolutionary literature were indeed seized at the Communist headquarters, rather than planted, and that the Nazi coup planned for March was wholly an invention of the real author of the memorandum, Wilhelm Münzenberg, the head of the Communist Agitation and Propaganda department, Agitprop, pointing out reports that forged orders had been circulated days after the fire in an effort to create a scare over a Nazi putsch. These were dismissed as fraudulent and commonly attributed to Münzenberg. Moreover, comparing the writing style of the memorandum to a pamphlet published by the Central Committee of the German Communist Party, Tobias comes to the conclusion that the Oberfohren Memorandum was also written by Münzenberg and later simply repurposed as a forgery thereafter attributed to Oberfohren following his suicide.

Propagandist Willi Münzenberg, via Wikimedia Commons

Likewise, Fritz Tobias casts doubt on the idea that Karl Ernst and others were executed on the Night of the Long Knives in order to eliminate loose ends and further cover up Nazi responsibility for the fire. Rather, he presents the more likely scenario that Ernst and his fellow Brown Shirt Storm Troopers were executed for all the obvious reasons: their political differences and the threat they posed to the National Socialist agenda. Then, as before, Willi Münzenberg seized on the opportunity to attribute a forgery to the fresh corpses that the Nazis had left in their wake. He points out that the two men named in the confession as accomplices in setting the fire had, embarrassingly, actually survived the S.A. purge and, with no reason to remain loyal to the Nazis, called the confession a fraud. And later, some of Münzenberg’s own fellow Communists named the “so-called Ernst testament” as an outright concoction edited by none other than Marinus van der Lubbe’s co-defendant, Georgi Dimitrov, the Communist leader lately acquitted of having had any part in the burning of the Reichstag.

In a world of political narratives handled so craftily by masters of public perception, our understanding of the past is not a matter of flat fact and hard documentation easily recalled. History was unreliable enough when it was written by the victors, but as can be seen in this story, now it can also be written by spin doctors, and the spotlight of truth can be purposely obscured by forgers and propagandists, leaving instead only blind spots.

*

Thanks for reading Historical Blindness. Review the podcast on iTunes if you can. Poke around the website to donate, read our blog entries and find links to our social media accounts and to my book on Amazon. And keep an eye out for our next full length episode, which will take you back to Germany, although about a century earlier…

Until next time... keep your eyes wide....