Dänikenitis - Part One: Wheels Within Wheels

In the public imagination, there is nothing outrageous about the idea that extra-terrestrials visited Earth and made contact with human beings, or even created human beings, in the ancient past. Indeed, it is such a common notion that we see it saturating the entertainment industry. For the last ten years or so, superhero films based on comic books have dominated the box office, and I’m not criticizing these entertaining films. I enjoy them. What’s interesting is that so many of them play with the notion of ancient contact with extra-terrestrials. The depiction of the old Norse Gods as actually having been inter-dimensional space aliens in the Thor films comes to mind. As does the 2021 film The Eternals, which portrayed a species of giant ancient aliens, the Celestials, who actually created humanity through genetic experimentation. A similar story was explored just this year in the final season of Star Trek: Discovery, resurrecting from an obscure episode of the nineties series Star Trek: The Next Generation a species called the Progenitors, ancient aliens who had created all life and all alien species in the Milky Way galaxy. We see it also in the 2012 film Prometheus, which expanded Ridley Scott’s Alien films’ mythology to reveal that a gigantic humanoid alien seen only as a skeleton in the first film was actually a member of an ancient alien species that had seeded the primordial Earth with its own DNA. Meanwhile, this popular trope, long exclusive to the realm of science fiction, has bled into the public’s understanding of history. In the nineties, the History Channel was thought of as the “Hitler Channel” with its focus on World War II docuseries, but in the 2000s, chasing viewers, it began to diversify into reality television and docuseries on more sensational topics, and in 2010, it premiered Ancient Aliens, which has become their tentpole program. To most, the series is a joke, the origin of numerous memes, usually involving the wild-haired UFOlogist Giorgio Tsoukalos, asking if a thing could ever be possible and then excitedly answering yes. The ancient aliens concept is now so thoroughly wedged into the zeitgeist that it seems impossible to dislodge it, to examine its claims and demonstrate its fundamental weakness in such a way that it might change minds. Even those who think the History Channel program is a joke may still believe that there is reason to think its underlying propositions are valid or convincing, especially with the juggernaut podcaster Joe Rogan frequently platforming people who promote the idea, like David Grusch, the congressional whistleblower who in the last year has made countless world-shattering claims about extra-terrestrials, none with actual evidence, including that aliens created humankind. Despite its ubiquity today, the notion of ancient aliens really only took hold of our imaginations in the 1970s. It was certainly in the 1970s that Marvel Comics legend Jack Kirby began to weave the notion of ancient aliens throughout the Marvel Universe. And this came in the wake of a major motion picture, 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, with its iconic depiction of ancient alien contact with early humanity, as ape-like hominids learned the use of tools in the presence of a mysterious monolith. But it is not this film along that accounts for the vast popularity of this idea during the seventies. Rather, it can be traced back to the huge popularity of one book during that decade, and its author, who may himself have taken some inspiration from the Arthur C. Clarke short story “The Sentinel” that had inspired Kubrick’s film. In order to get to the root of the ancient astronaut theory that has become so entangled in modern thought, we must trace it back to its origin point, the primary vector for its propagation, and consider the actual arguments made in that book, Chariots of the Gods by Erich von Däniken.

In my series Pyramidiocy, on the myths and misconceptions about the Pyramids and ancient Egypt, I spoke already about the ancient astronaut theory as it relates to nonsense about the Great Pyramid, and I spoke specifically about Erich von Däniken. More importantly, here at the beginning of this series, I spoke about the origin of the idea of ancient alien contact with Earth, as it originated from some of the same people as had made up nonsense about ancient Egypt and Atlantis: namely Helena Blavatsky and other Theosophists. As I spoke about in my episode on the Religious Dimension of UFO Belief, there was a circuitous throughline, from the Christian mysticism of Emanuel Swedenborg to the spirit channeling of mediums to Blavatsky’s Theosophy. Swedenborg claimed to take spiritual journeys to inhabited worlds, Spiritualists claimed to channel not just ghosts but also extra-terrestrial intelligences, and the medium Blavatsky, claiming to have been tutored by enlightened beings and to have mental access to the Akashic Record, a hidden history of everything, fleshed out a timeline in which ancient aliens from the Moon and Venus helped mankind develop on lost continents. And of course, there was an element of white supremacy in her work, which focused so much on root races and the superiority of Aryans. Aside from the very specific claims of Theosophists, the notion of ancient aliens was really only toyed with, such as by Charles Fort, a well-known compiler of reports on anomalous phenomena, or “Forteana,” who speculated on the possibility that stories about demons could actually reflect visitation from otherworldly beings who had tried to colonize the ancient Earth. Both the claims of Theosophists and the musings of Charles Fort were influential on the young science-fiction author H. P. Lovecraft, who transformed the inchoate ideas into a cohesive science-fiction legendarium involving a “pseudomythology” that featured ancient monstrous deities from outer space who had long lain dormant. It’s thought that Lovecraft also took inspiration from Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem “The Kraken,” which spoke of that sea monster’s “ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep,” as well as from The Gods of Pegana, a 1905 collection of fantasy stories in which the author, Lord Dunsany, invented a pantheon that included a chief god that had been lulled to sleep and was expected to wake again. But we know that Lovecraft read Theosophical works, and much as those same works grew in popularity in late 19th century Germany, contributing to notions of the German inheritance of Hyperborean Aryan superiority, so too they may have contributed to Lovecraft’s white supremacist views, which showed through clearly in his fiction, with his rejection of miscegenation as an abomination depicted in stories about humanity being corrupted by inhuman bloodlines. As I explained before, all ancient astronaut theories descend from these threads, from Theosophy and the scifi of Lovecraft, and thus derive from racist ideas.

19th century art of the Kraken by John Gibson. The poem by Alfred, Lord Tennyson about this legendary monster of the deep may have inspired Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos.

As is probably true of other widespread concepts and how they enter the cultural zeitgeist, the man credited with bringing the idea to the public’s attention, and who for most of his career has enthusiastically taken credit for originating the notion, really only repackaged the ideas of others who are now largely forgotten. In a very real way, Erich von Däniken is just a thief. He was born in 1935, in Switzerland. He was raised Catholic, but as a young man he rejected his father’s faith as he became more and more interested in UFOlogy. His willingness to resort to theft first showed in 1954, when he was convicted and given a four-month sentence for pilfering money from a camp where he worked as a counselor and from an innkeeper. His sentence was suspended, but a psychiatrist who examined him at the time declared that he showed a clear “tendency to lie.” His father pulled Erich out of school after his trouble with the law and apprenticed him to a Swiss hotelier, and von Däniken seems to have taken from his earlier brush with the law a sense that innkeepers were easy marks, for he was later convicted of embezzling money from his new hotel position, this time serving nine months for the crime. Somehow, he managed to continue his employment in the Swiss hotel industry after this, and eventually he worked his way up to becoming the manager of the Rosenhügel, a sports hotel in Davos. It was while employed in this position that he began to research and write the book that would eventually be published as Chariots of the Gods, under its original title Memories of the Future. More than a dozen publishers rejected his manuscript, but eventually, the publisher Econ-Vorlag took an interest in 1967. The publisher recognized that the book could potentially strike a chord with the public, tapping into modern ideas about extra-terrestrial life then being considered by great astronomers like Carl Sagan and reflecting the growing modern disbelief in God, which had become popular in the 1960s with the spread of the phrase “God is dead.”

The problem was that von Däniken’s manuscript was an unfocused mess. His publis’er thus brought on an editor, Wilhelm Roggersdorf, to improve it, and it was Roggersdorf who apparently rewrote the book and transformed it into the seminal work on ancient astronauts that it became. It is perhaps relevant to note here that Roggersdorf was a pen name, and this editor was actually Wilhelm Utermann, formerly a Nazi propagandist who had edited the Nazi Party’s mouthpiece newspaper. The connections between ancient astronauts theory and Nazi race ideology are many and various. But back to Erich von Däniken; it appears that while he had been managing the Davos hotel and working on the book, he took many an expensive trip to South America, for example, and to Egypt and elsewhere, seeing for himself some of the sites that he wrote about in the book. In late 1968, he was arrested for the third time, once again charged with fraud and embezzlement and also with forgery, for he had apparently been cooking the hotel’s books, stealing from the business and misrepresenting his finances in order to obtain loans to pay for his travels. His absurd defense was that he had meant no harm, that as a writer he could not help sacrificing his morals to pursue his obsessions, and that it was the job of the creditors he had defrauded to investigate his loan applications more thoroughly. Unsurprisingly, a psychiatrist appointed by the court declared him to be a criminal psychopath. But it mattered little. By this time, his ex-Nazi editor had turned his book into a sensation, and it had become the bestselling book in Germany. He was able to easily pay the court’s fines and his outstanding loans. Soon, “Dänikenitis” would sweep the world, as his book and the theories it promoted became a sensation, inspiring further books and documentaries, as well as the science fiction of comic books and films. According to German magazine Der Spiegel, who coined the term Dänikenitis, his success can be attributed mostly to “folly, fraud, and business acumen.”

Erich von Däniken in the 1980s.

Erich von Däniken has protested against the raising of his criminal record in the evaluation of his work. He argues first that he was innocent—all three times he was convicted of the same crimes—and second that his criminal record is not relevant to his theories. It is little more than an ad hominem attack, he complains, poisoning the well in order to unfairly put all of his arguments in doubt. I will grant this, but I raise his criminal past for historiological purposes, to demonstrate that his thievery (and I need not qualify that as alleged, since he was convicted of it every time), in order to draw a further parallel with his liberal borrowing of other people’s ideas. In the recent conclusion to my series on pyramid myths, I discuss the work of Jason Colavito, who traces the entire concept of ancient astronauts from Theosophy to von Däniken through Lovecraft by way of the French writers Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier, whose book Morning of the Magicians preceded von Däniken’s by nearly a decade. In it, Pauwels and Bergier suggest that “it is quite legitimate to imagine that ‘Strangers from Beyond’ have been to inspect our globe, and have even landed….” In a strikingly similar fashion to the Ancient Aliens meme, they write, “Have we already been visited by the inhabitants of Elsewhere?” and then immediately answer, “It is highly probable.” And indeed, since so many examples and supposed pieces of evidence that von Däniken raises for his thesis were raised also by Pauwels and Bergier, Von Däniken was forced to include a citation for their book in the bibliography of later editions. Nor was this the only instance of von Däniken stealing from other writers and being forced to document them as sources only under threat of lawsuit. Very much the same thing happened with the book One Hundred Thousand Years of Man’s Unknown History by Robert Charroux, another French author who had taken up the ancient astronaut theory in 1963, five years before von Däniken’s book came out. While Pauwels and Bergier’s work was focused largely on compiling every weird fringe claim they could, with only passing theorizing on alien visitation in the past, Charroux’s work came to this explicit conclusion. After numerous chapters touting supposed evidence of lost continents and ancient high technology, he builds up to a chapter actually called “Extraterrestrials Have Come to Our Planet,” and this becomes a central argument. And he too partakes of the same sorts of rhetoric, ridiculously presaging the Ancient Aliens meme. When listing unsupported claims of there being a space base on the Moon, he writes, “Are we to conclude that these lunar craters have been frequented by extraterrestrial astronauts?” and immediately answers his own question, stating with confidence, “The possibility cannot be rejected.” Interestingly, not only did Erich von Däniken steal his thesis from these books, and nearly all the supporting examples that he discusses, he also takes from them his rhetorical style, which touches on his supposed evidence only In brief outline, then launches into long series of questions and thereafter moves on and refers back to the questions he raised as if they were solid points he has already established.

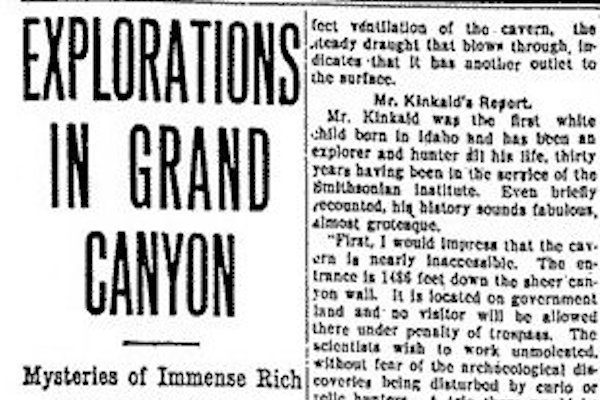

Von Däniken tries to preemptively address criticism of his arguments in his book by saying “Admittedly this speculation is still full of holes. I shall be told that proofs are lacking. The future will show how many of those holes can be filled in.” So let us look now at his supposed proofs and see how well holes have been filled in the 56 years since the book’s publication. One of the first pieces of “evidence” he raises is the Piri Re’is Map, which should by now be very familiar to my listeners. This map was actually only recently discovered, in 1929, when the old Imperial Palace of Constantinople was being turned into a museum. In the 1930s, it garnered scholarly attention, as it appeared relatively accurate for a 16th-century map, and the cartographer, Piri Re’is, an Ottoman navigator, makes mention in the marginalia of the map that he had based his map on a number of existing maps, Iing a now lost map created by Christopher Columbus. The entrance of the Piri Re’is Map into fringe pseudohistory came as the result of its depiction of a coastline that stretched both west and south of Africa. Clearly at least part of the landmass depicted is meant to represent South America, as Rio de Janeiro is unmistakably pictured. There are a variety of reasons why the South American coastline is thereafter depicted as sloping eastward, toward and beneath the African continent, the most obvious being that the rest of the continent had not yet been mapped. This, in conjunction with notions about terra australis and the hypothetical balancing of landmasses on the different hemispheres of the planet may have caused Piri Re’is to imagine the size and dimension of South America that way. Then there is the additional notion that, since the edge of the parchment used actually curves the same direction, he was actually just using the space available to him to depict the continuing coastline, without a real sense of its accuracy. But in the 1960s, a certain theory, championed by one Charles Hapgood, a New Hampshire state college history teacher, suggested that this was actually depicting Antarctica, and this false idea simply hasn’t been shaken. You hear Graham Hancock prattle on about it quite a bit, for example. Hapgood himself was more of a catastrophist, denying the science of continental drift and arguing that in the distant past, the Earth’s poles reversed, thus Antarctica was not always a frozen landmass. But like all the pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact theorists and ancient lost civilization theorists who rely on his theory, his argument rests on the idea that the Piri Re’is map was based on some lost ancient maps.

The Piri Re’is map.

Pre-Columbian Trans-Oceanic Contact theorists attribute Piri Re’is’s source maps to ancient mariners, and lost civilization theorists attribute them to, you guessed it, lost civilizations. Ancient astronauts theorists attribute them to, you’re right again, ancient aliens. What’s ridiculous is that Piri Re’is describes his source maps on the marginal notes of the map itself, identifying them not only as Columbus’s lost map but also as being Arabic and Portuguese maps, as well as mappae mundi, or medieval Christian world maps. But ancient astronauts theorists take their claims about the map much further, declaring that it could only have been drawn from an aerial view of the world. Pauwels and Bergier suggested it first in their customary series of questions, asking, “Were these copies of still earlier maps? Had they been traced from observations made on board a flying machine or space vessel of some kind? Notes taken by visitors from Beyond? We shall doubtless be criticized for asking these questions.” Then Charroux followed suit, claiming, “As for the means by which the surveys were made…they could only have been aerial.” Von Däniken merely repeats them, and repeats their mistake in referring to the singular Piri Re’is map as a set of maps (another sign of his plundering of their material), and taking their claim that the map is suspiciously accurate even further, claiming it is “absolutely accurate” and asserting that originals of Piri Reis’ maps must have been aerial photographs taken from a very great height.” The precision of the Piri Re’is map is a blatant lie that can be easily discerned by anyone comparing it to an accurate world atlas. But it’s quite apparent that these authors weren’t too concerned with accuracy. Pauwels and Bergier wrongly state that Piri Re’is himself presented his maps to the Library of Congress in the 19th century, which would have been quite a feat for a 16th-century Ottoman. Von Däniken claimed that the map (or maps, in his verbiage) were discovered in the 18th century, only about 2 centuries off the mark. The closest was Charroux, who very specifically said the map was discovered in July of 1957, when in fact it was discovered in October of 1929. These inaccuracies seem to indicate that all these guys were careless in their research and perfectly willing to misrepresent facts in order to create mystery where it otherwise does not exist.

Keeping this in mind, let us move on to Erich von Däniken’s further claims in Chariots, which look much further back than 16th century maps, finding the presence of aliens in the Bible. Here he raises ideas that I have addressed ad nauseum in the past, such as that the Genesis story about the “sons of God” who fathered “Nephilim,” typically translated as giants, with human women is really a story about genetic engineering and hybrid species. If you want to hear all the reasons for us to doubt that “sons of God” even referred to angels, or that “Nephilim” even meant giants, or that any giants ever actually existed, I did a whole series about it a couple years ago called “No Bones About It.” Check it out. He also raises the idea that the Ark of the Covenant was a high-tech device, something I have touched on a few times. You can hear a great deal more about the legends surrounding the Ark in my episode The Whereabouts of the Lost Ark of the Covenant. He spreads the further interpretation that, the pillars of fire and cloud that led the Israelites out of Egypt were actually alien craft, and when God descended on Mount Sinai, it wasn’t just a thunderstorm, as the text would suggest, but rather the arrival of a spacecraft, all notions I have again discussed before, in my episode on the Religious Dimension of UFO belief as well as in my recent episode on the Bible Code. In putting forth these claims, he moves away from his most obvious French sources, and instead borrows from the works of UFOlogists who had already raised the notion of certain Bible stories actually referring to aliens, such as Brinsley Le Poer Trench, who in his book The Sky People asserted that not only were the Nephilim a hybrid offspring of aliens and humanity, the creation of Adam and Eve was also just an experiment conducted by extra-terrestrials. Perhaps more influential overall on the ancient astronaut theory was Morris K. Jessup, whose 1956 book UFO and the Bible was the first to suggest that “There is a causal common denominator for many of the Biblical wonders; and …this common cause is related to the phenomena of the UFO.” You may remember me mentioning Jessup in regards to the connection made between his tragic suicide and the Philadelphia Experiment hoax. In his prolific writings, Jessup was one who anticipated the Dänikenitis to come. Another was M.M. Agrest, a Russian mathematician who wrote extensively on the prospect of “paleocontact,” specifically suggesting that the destruction of Sodom and Gommorah was actually the result of a nuclear detonation, as ancient aliens wanted to destroy their nuclear stockpile and thus warned the inhabitants of the cities to flee the coming atomic destruction. This claim came to von Däniken by way of Charroux, who repeats much of Agrest’s claims without question. What both should have asked is why these aliens wouldn’t just detonate their nukes somewhere uninhabited. They might also have asked why the destruction was described as fire and brimstone raining down, when a nuclear detonation would appear to be a rising cloud of fire. Many have been the theories about the historicity of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, but this one is just ridiculous. A more rational one, published a few years ago in Nature, suggests that it may have been the result of a meteor strike, or more specifically, a cosmic airburst as is thought to have happened over Tunguska in the early 20th century. But of course, von Däniken and his French predecessors think the Tunguska Event was also the result of alien nuclear technology.

A late 16th-century depiction of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah

Perhaps most telling of Erich von Däniken’s desire to see extraterrestrials in Bible stories are his tortuous twisting of scriptures to fit his interpretation. It has been noted before, by Richter Jonas in a 2012 scholarly article entitled “Traces of the Gods: Ancient Astronauts as a Vision of Our Future,” that just as Greeks remade Egyptian and other mythology through their own lens, nterpretation graeca, and the Romans then reinterpreted Greek mythology to suit their own culture, nterpretation Romana, what Däniken seems to be doing could be called nterpretation technologica, reinterpreting myths to suit his own worldview. For example, he scours the scriptures for passages that might refer to spacecraft, and some are a real reach. His title, Chariots of the Gods, seems to derive from his creative interpretation of a couple Bible passages. One is Elijah’s translation into heaven, saying that he was taken up by a “chariot of fire.” In fact, what it says in 2 Kings is that a chariot of fire, driven by horses of fire, came between Elijah and his son, and then Elijah is actually carried into heaven “by a whirlwind.” Von Däniken keeps the chariot of fire image and does away with the whirlwind, because one seems to work with his argument and the other doesn’t. And more than that, he then inserts the chariot of fire image into other stories that never included it. For example, Enoch, whom the Bible only says “was no more, because God took him away,” but von Däniken, either in error or through purposeful transposition claims that “according to tradition, [Enoch] disappeared forever in a fiery heavenly chariot.” Likewise, von Däniken saw in Ezekiel’s vision of God a detailed description of an alien spacecraft, described as a “wheel within a wheel,” able to move “in any of the four directions without veering.” Having spoken about this vision before, in my episode on UFO religions, you may already realize that this description in Ezekiel’s inaugural vision was of God on his throne, carried aloft by angels. Nine chapters later, when again Ezekiel sees these living creatures beside the wheels, he explicitly says these were cherubim. More than that, these flaming wheels within wheels, which are covered in eyes, came to be identified with the Throne itself, a class of angels called ophanim. What makes Von Däniken’s discussion of this vision less than honest is that he again omits whatever doesn’t work well with his interpretation. For example, he only partially quotes Ezekiel 1:1, including “the heavens were opened,” but omitting “and I saw visions of God.” He is misrepresenting his sources, cherry-picking only what makes his claims sound convincing, and this is characteristic of all his work, as we will see in Part Two of this series. What’s curious to me is that, though he renounced his religious background and his efforts to undermine the religious views of his father are clear in his work, he nevertheless seems to understand his ancient astronaut theory as a kind of religious view. He has said that the basis of his theories first came to him in visions during his incarceration. And though he claims to be challenging orthodox science with legitimate scientific evidence, when he defends his claims against criticism, he tends to refer to it as if it is religious belief and therefore unassailable. “[W]hen I compare it with the theories enabling many religions to live unassailed in the shelter of their taboos, I should like to attribute a minimal percentage of probability to my hypothesis,” he says, which is just a convoluted way of saying his ideas may not hold water, but they’re at least as believable as religion. And when, in an interview, he was directly confronted about his cherry picking, he said, “It’s true that I accept what I like and reject what I don’t like, but every theologian does the same.” It almost seems like von Däniken never really believed his claims about ancient astronauts and only expressed them as a kind of satire of religious belief. Were it not for the fact that he has led so many to believe in his theories, I might actually appreciate them as an elaborate refutation of religion.

Until next time, remember, whenever someone like von Däniken or Hancock tells you that they are unfairly criticized by “orthodox” academics simply for “asking questions,” that means their ideas have been disproven and they’re resorting to claims of being victimized just to save face. Von Däniken did not write Chariots of the Gods in good faith. He knew before its publication that it would be refuted. That’s why in the first paragraph of his introduction, he says “scholars will call it nonsense” but sets up himself and those who will believe him as somehow better than all experts, saying in his first sentence, “It took courage to write this book, and it will take courage to read it.” And I guess it does take a kind of misplaced courage to be insistently wrong in the face of all contrary evidence. Or maybe we call that obstinacy, not courage.

Further Reading

Gershon, Livia. “Ancient City’s Destruction by Exploding Space Rock May Have Inspired Biblical Story of Sodom.” Smithsonian Magazine, 22 Sep. 2021.

Colavito, Jason. “The Origins of the Space Gods: Ancient Astronauts and the Cthulhu Mythos in Fiction and Fact.” 2011, www.jasoncolavito.com/uploads/3/7/5/9/3759274/the_origins_of_the_space_gods.pdf

Richter, Jonas. “Traces of the Gods: Ancient Astronauts as a Vision of Our Future.” Numen, vol. 59, no. 2/3, 2012, pp. 222–48. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23244960. Accessed 12 July 2024.

Story, Ronald. The Space-Gods Revealed: A Close Look at the Theories of Erich von Däniken. Harper & Row, 1976.