Pyramidiocy - Part Five: The Curse of the Pharaohs

It is no surprise that fiction about Egyptian crypts and mummies would develop as tropes of the horror genre. On the surface, they are obviously related to death and burial, which was a common subject mined by horror authors in the 19th century. Think, for example, of Poe’s stories of being buried alive or Mary Shelley’s tale of grave robbery and resurrection or Stoker’s use of old folklore about revenants in his invention of the modern vampire story. But more is at work here. Egyptomania led to some exceedingly horrific phenomena in the Victorian era. These Victorian writers were influenced by the aesthetic of the Gothic literature that preceded their work, but they must also have been influenced by the macabre preoccupations of their time. Victorians in general developed a morbid fascination with death. Indeed, they have been compared with so-called “dark tourists” of today. With the progress of medical science and the technology of waxworks, medical museums became popular tourist attractions, where ladies and gentlemen paid the price of admission to see both wax models and preserved physical specimens that demonstrated a variety of diseases. In Paris, the morgue itself became a popular attraction, where people could view freshly executed criminals and the corpses of children tragically dead before their time. This interest in the macabre was not new. In the late 18th century, Madame Tussaud, famous for her waxworks, started her career by taking death masks of people just after their execution, such as she did with the guillotined head of Marie Antoinette. But it wasn’t until the 1830s and ‘40s that she made her fortune with exhibitions like her Chamber of Horrors. And Egyptomania had brought with it fresh fodder for the ghoulish interests of Victorians. This fascination with death makes it even more apparent why mummy-viewing was a popular roadshow, like the one that passed through Ohio and captured Joseph Smith’s attention in the 1830s. It turns out, Egyptian mummies were a tourist draw all over. At the Royal College of Surgeons in London, mummies were unwrapped and examined for anatomical study and craniometry, and much like the Paris Morgue, they charged admission. Indeed, mummy unwrapping parties became quite popular, even outside the confines of academia, as aristocracy purchased their own mummies and hosted their own private unwrappings. Much was made of the inhalation of “mummy dust” at these parties, as for centuries, the flesh of mummies was thought to have medicinal qualities. This goes back to notions about how they were embalmed. Indeed, the ingestion of mummy powder, or “mummia,” which was basically just ground up mummies, was long believed to be a panacea or cure-all, and today is remembered as a form of quackery likened to snake oil. So even as late as the 1800s, we see Egyptomania encouraging what was essentially cannibalism. So popular were mummies for road shows, unwrapping parties, and medicine that it is said mummies became very scarce in the Victorian era. When they had all been robbed from their tombs, the unscrupulous were apparently not above passing off any old desiccated corpse as a mummy. One report had it that a certain purveyor of mummies would get ahold of any corpses he could, stuff them full of bitumen and dry them out in the sun so he could sell them to European apothecaries. Anther story claimed that the Prince of Wales, on a visit to Aswan, was shown a mummy in a sarcophagus that was actually an Englishman who had died and dried out in the desert. Rumors abounded regarding the mass waste of these Egyptian antiquities. Mark Twain joked about mummies being burned as coal to run locomotives, but some believed him. Likewise, l9th century newspapers claimed that most American paper products, including postcards and even their own newsprint, were made out of mummy wrappings, of which there was a great overabundance because of the popular use of mummies. Some even framed it as a warning to “[p]eople who are in the habit of chewing paper,” suggesting they may not want to use mummy wrappings “for mastication purposes.” While it is true that printers in America, which produced more newspapers than any other country, had reached a crisis in the 1850s and had turned to importing rags from Egypt for paper manufacturing, linens were a major industry in 19th century Egypt. There is no evidence that the rages imported for American paper were actually mummy wrappings, and in all likelihood, this was a piece of sensationalist fake news. As it turns out, many were the false and exaggerated claims printed in 19th century newspapers that would contribute to the further spread of myths about Egypt and her pyramids.

As I began to discuss in the last installment, there is a long history to the fictional tropes of stories involving resurrected mummy’s and curses. As indicated in the cold open, we might trace Victorian interest in the topic to Egyptomania and the general macabre preoccupations of the era. While they may have little to nothing in common with vampire stories, which derived from European folklore about revenants, itself evolving out of a poor understanding of the decomposition of corpses—for more on that, check out my series on vampire legends—they certainly do connect with tropes in the work of that other Shelley, not the poet Percy Bysshe, whose poem “Ozymandias” demonstrated his own preoccupation with Egypt, but that of his wife Mary, author of Frankenstein. The very first mummy story, which I mentioned previously and which appeared nearly a decade after Frankenstein, featured a mummy being reanimated with electricity, much like Frankenstein’s monster. Many a made-up mummy would likewise be revivified, such as the one in Poe’s Some Words with a Mummy, which was first unwrapped in a Victorian party and afterward shocked to life. Even the very first silent mummy horror movie in 1911 featured a mummy brought to life through the power of electricity. Of course, the idea of a resurrected mummy must have derived in part from the growing understanding of Egyptian mythology and the ancient belief that preparing their dead ensured their successful rebirth in the afterlife. But this idea of electricity bringing them to life came from the popularity of galvanism in the late 18th and early 19th century. Galvanism was named after Luigi Galvano, who discovered that dead frogs moved when electrified. Displays of galvanism, the shocking of dead animals and even dead people, was very popular for years, yet another example pre-Victorian interest in the macabre. People tended to think the electricity had actually resurrected the dead momentarily, rather than just artificially contracting their muscles, and some even swore that the dead spoke when thus reanimated. While the notion of the risen mummy may have been a Victorian spin on actual ancient Egyptian beliefs, the notion of a mummy’s curse, which became so prevalent in myths about ancient Egyptian tombs, was a bit older and seems to have derived from later legends that had no real connection to actual Egyptian beliefs. One of the earliest versions of a mummy’s curse tale also has mummies returning, but only as ghosts. At the dawn of the 17th century, a Polish royal claimed to have bought mummies in Alexandria and chopped them up in order to smuggle them past Ottoman officials, who were supposedly worried about mummies being used for magical purposes, when in reality they were probably only being ground into dust and ingested as medicine. According to this Polish prince’s report, their ship thereafter became troubled by storms and visions of the mummies’ ghosts led him to throw the mummy parts into the sea. So as far back as we can trace it, the curse of mummies was associated with vengeful spirits. The Hellenistic legend of Setna, with its tomb full of ghosts and cursed magical book that must not be taken out of the tomb, may have been an early forerunner of the mummy’s curse legend. Likewise, the medieval pyramid legend of Sūrīd, with its idols that struck dead any who entered the pyramid, may also have contributed to notions of the tombs themselves being magically protected or cursed. It has been speculated that this part of the legend may have been inspired by the superstitious fear that pierced the hearts of Arab tomb raiders when opening a tomb and finding statues there in the dark, staring at them. These legends were clearly rampant among Arab and Coptic Egyptians as well. Numerous European travelers in the 19th century wrote that residents of Cairo believed tombs were haunted by ifrits, which may have meant a kind of demon or djinn, but which Muslim Egyptians seem to have basically taken for ghosts. Legends about the pyramids being cursed or haunted by demons or ghosts were surely encouraged by the fact that, according to later Victorian reports, wild animals, specifically jackals, had taken up residence in the cramped passages and hollows of the pyramids. These legends were carried to the European and American public and transformed into horror tropes, and in the early 20th century, they became fodder for sensationalist newspaper articles that would promote anything to grab attention at the newsstands.

A 1909 Pearson’s Magazine cover. This edition featured a mummy story and used a picture of the mummy-board on the cover, and this may be the origin of its association with a curse.

On April 15th, 1912, the massive British ocean liner RMS Titanic struck an iceberg and began to sink. The event is etched in the public imagination of everyone the world over, especially since the global sensation over James Cameron’s film about the tragedy. We can all summon to mind images of Edwardian ladies and gentlemen woken from their sleep, stumbling out of their luxurious cabins only half dressed and facing their mortality. Many were the small dramatic moments among the passengers as they discovered there were not enough lifeboats. One moment was when W. T. Stead, the most famous newspaper editor in all the British Empire, helped women and children aboard the lifeboats and gave his life jacket to someone in need. Survivors of the Titanic’s sinking later told stories about Stead’s final days aboard the ship, and about his entertaining conversation during dinner the night before his drowning. Supposedly, he regaled those near him with stories about a certain wooden “mummy-board,” or sarcophagus lid, that had been donated to the British Museum in 1889. Stead claimed in dinner conversation, according to later reports that were printed in newspaper stories about his death, that this Egyptian artifact was cursed and brought misfortune and catastrophe to those who encountered it. Of course, there is no evidence that Stead actually made these claims beyond the reports about his last meal on the Titanic, but it wouldn’t have been out of character. Stead was both admired as an advocate for reform in his newspapers and also maligned as a sensationalist who would gladly stoop to printing entirely false stories if it sold his papers. He is viewed as a forerunner of British tabloid journalists. But whether or not he actually told such stories about the mummy-board, the humbug was already in print and would continue to be embellished in further newspaper stories. As the urban legend evolved, it was said that this lid was actually a complete sarcophagus, and it was rounded out to include an actual cursed mummy, called the Unlucky Mummy. And it was claimed that a certain journalist who had written about the mummy-board in 1904 had died because of its curse, even though he actually died three years after writing about the mummy-board from a typhoid fever caused by a Salmonella infection, an illness that commonly plagued many British living abroad, killing some 15,000 troops during the Boer War. As the legend expanded, it was claimed that the Unlucky Mummy was actually on board the Titanic when it sank, making the tragedy actually the result of the curse. And more than that, it was claimed that the artifact survived, perhaps used as a makeshift raft by some unlucky passenger who let go and succumbed to the waters when his feet were frozen, as had been the case with Stead, and astonishingly, the mummy could be traced to two other shipwrecks, having been onboard both the Empress of Ireland, which collided with a collier 2 years later, and the Lusitania, sunk by a German U-boat the year after that. But all of this was utterly fake news, as in 1934, with claims about the Unlucky Mummy still running amok, an Egyptologist felt compelled to point out that there was no mummy, nor even a whole sarcophagus, and that the mummy-board in question had never left the British Museum.

The urban legend of the Unlucky Mummy merely presaged the biggest fake news sensation relating to a cursed Egyptian tomb and mummy: that of King Tutankhamen. In 1922, Egyptologist Howard Carter made perhaps the greatest discovery of modern times, and one which helps to disprove many fringe claims about the pyramids. One common objection to the academic consensus that pyramids were pharaonic tombs is that nothing was found within, despite the fact that we know from medieval Arab sources that the pyramids were entered and robbed, and despite the further fact that almost every pharaoh’s tomb was likewise emptied. The discovery of King Tut’s tomb proved this, as it had only remained intact because it had been dug into the floor of the Valley of the Kings and had long ago been covered by materials from the construction of later pharaohs’ tombs. Stories about Carter’s discovery of the boy-king’s tomb, filled with gilded statues and other furniture that glittered by candlelight, threw new fuel on the fires of the waning Egyptomania of the 19th century, setting off a new craze called Tutmania. But when the bankroller of the excavation, the Earl of Carnarvon, died several months after the opening of the burial chamber, rumors of a mummy’s curse began to rumble. As the story of the Unlucky Mummy showed, real life mummy’s curse claims were not new, and they typically followed when anything unfortunate happened to anyone who had encountered a mummy. For example, in 1885, one Walter Herbert Ingram bought a mummy in Luxor and gifted it to a certain British noblewoman. When three years later he was trampled by an elephant that he was shooting at while hunting. This became a mummy’s curse story, even though he obviously brought it on himself by hunting elephants. In the case of King Tut, Carnarvon had long struggled with poor health, and he died because of a mosquito bite that became infected. He probably should not have been tramping around Egypt in his frail condition. But with the notion of a curse already in the public mind, any ensuing misfortune would be blamed on the curse. One visitor to the tomb would die the following month of pneumonia, but there were hundreds of visitors to the tomb daily as a result of Tutmania. One study has even shown that, statistically, visitors to the tomb were not more likely to suffer untimely deaths. And then it was claimed that the curse spread beyond those who actually visited the tomb to those connected to the tomb’s discoverers, like Carnarvon’s half-brother, who would die a few months later after having all of his teeth pulled on bad medical advice. Even many years later, whenever any of those involved would pass away of an illness, this very picky and slow-acting curse was blamed.

Tourists crowd around King Tutankhamun’s tomb. Most are just fine.

The myth of the curse of King Tut was created and spread by the press. Tutmania was already selling newspapers for them, and newspapers were only too happy to print wild speculation and legends when it would garner the reading public’s attention. In the midst of Tutmania, for example, William Randolph Hearst, the godfather of yellow journalism, syndicated an article that claimed the Great Pyramid was one and the same as Noah’s Ark, that the Ark was no boat but rather this building created to survive the flood, and on whose exterior can still be seen the high water mark. The article just regurgitated Arab-Egyptian legends from the Middle Ages, with the bold assertion that “science” had made this determination. When the additional aspect of a pharaoh’s curse became attached to the story of King Tut’s tomb, newspapermen couldn’t help themselves. They ran with it and sought out anyone willing to lend support to the claims. If they were going to lean into this occult angle on the story, then they thought they’d better get some occult experts to weigh in, so they contacted celebrities with some interest in the occult. One of them was Arthur Conan Doyle, author of Sherlock Holmes and spiritualist, who in the 1890s had written two stories about reanimated and vengeful mummies. Doyle obliged, giving the American press a juicy quote: "The Egyptians had powers that we know nothing of. They easily may have used those powers, occult and otherwise, to defend their graves.” He concluded by speculating that Egyptian priests had conjured “elementals” to attack tomb robbers, which is a far cry from the reality of an infected mosquito bite. One of the biggest purveyors of old myths who responded to the press was one Marie Corelli, a novelist who promoted fringe beliefs in her work. Corelli misquoted and incorrectly cited a number of medieval Arabic works whose legends we have already discussed, which originated legends like that of Sūrīd with its magical pyramid guardians and Hermetic legends about Egyptian tombs being full of alchemical elixirs, suggesting that perhaps those who died had actually come into contact with some ancient poison. This suggestion, though based on legends that arose far later than the construction of Egyptian tombs, nevertheless were used as a kind of rational version of the King Tut curse claims, thereby lengthening its life. As this urban legend took on a life of its own, kind of like an awakened mummy, it gathered other elements, such as that a literal curse was inscribed on the walls of the tomb—that pesky magical inscriptions myth. It was claimed that the inscription said something like “After any man who shall enter this tomb to usurp it, I will receive him like a wild fowl and he shall be judged for it by the great God,” and it morphed through endless retellings to become “Death shall come on swift wings to him that toucheth the tomb of the Pharaoh.” But no such inscribed curse has ever been documented on the tomb walls, or over its doorway, or on any of the objects discovered within. Nevertheless, this claim, and others about the “curse of Tutankhamun,” continue to be made even today. Their popularity in the press would last throughout the 20th century, as even decades later, when someone peripherally related to the digs happened to pass away, major newspapers would throw an insinuation into their obituaries that their demise, no matter the cause or how natural it had been, was caused by the mummy’s curse.

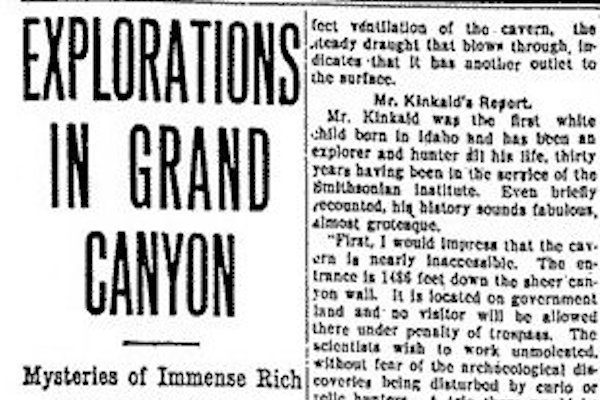

Not all of early 20th century fake news and hoaxes about Egyptian burial structures, like the pyramids, were related to the curse of the pharaohs myth. Some tied in to other myths we have discussed. For example, as Jason Colavito reveals in my principal source for this series, Legends of the Pyramids, which remains the best and most complete book providing an overview of these myths and misconceptions, in 1909, around the same time that the “mummy-board” in the British Museum was earning a reputation as a cursed artifact, a sensation occurred when grains were discovered in the Great Pyramid, seemingly providing evidence for the old myth that they were, in fact, Joseph’s granaries. However, when these discoveries went from dried grain native to Egypt to maize, a distinctly American crop, it was discovered that it was all a prank. Arab-Egyptians had placed these objects within the pyramid to make a mockery of European Christians who still clung to the long disproven notion that Joseph had built the structures. But there were those who would look at the maize planted in the pyramid and claim it was proof of prehistoric Egyptian contact with the Americas. Avid followers of the podcast will recall my recent series on Pre-Columbian Trans-Oceanic Contact myths. While this was long before Afrocentric Hyperdiffusionists like Ivan Van Sertima would make their claims, the notion was already circulating, having been proposed by Atlantis theorists like Ignatius Donnelly and his French predecessors. Also in 1909, when pranksters were leaving maize in the pyramids, here in the U.S., the Arizona Gazette printed a story claiming that two archaeologists from the Smithsonian had discovered a warren of tunnels beneath the Grand Canyon, within which they had discovered a massive cache of Egyptian artifacts, hieroglyphic inscriptions, and mummies! The fact that this was a hoax article should have been immediately apparent, simply from the way it identifies one of the Smithsonian archaeologists as “the first white child born in Idaho,” insisting that “his history sounds fabulous, even grotesque.” The character was clearly a fiction, as would later be confirmed, for none of the characters named had ever worked for the Smithsonian Institution, which the article called “Institute.” As it turns out, they seemed not to exist anywhere. The article further tips its hand when it insists that readers not go looking for this cavern, which the author assures “is nearly inaccessible.” And the confusion between Egyptian culture and Tibetan culture shown in the article’s description of the artifacts is enough to make apparent that it was not reporting an actual archaeological find. Most likely, it was written by famous newspaper hoaxer Joseph Mulhatton, the Liar Laureate, to whom I devoted an early episode of the podcast. Nevertheless, despite the clear falseness of this report, it continues to be touted by the fringe today as evidence of Pre-Columbian Trans-Oceanic Contact, or of some lost precursor civilization such as the mythical Atlantis, evidence of which, like that for giants, they claim the Smithsonian is actively covering up.

The hoax newspaper article itself

And so we enter the fringe. We dipped into the fringe already, throughout the series, with old pyramid legends entering occult beliefs, but as we approach the modern day, we find that is where all of these myths survive. Throughout the 20th century, occultists have more and more embraced misconceptions and misguided notions about the pyramids and created numerous branching belief systems with these myths at their heart. In the late 19th century, Charles Taze Russell embraced the pyramidology of Charles Piazzi Smyth, coming to believe that Hebrews built the Pyramids of Giza according to divine instruction, and that its measurements and dimensions could be used to foretell the future, making a series of predictions about end times occurrences coming in 1914, none of which actually took place, of course. Russell’s millenarian movement would become the Jehovah’s Witnesses today, who never seem to want to talk about this stuff with me and act offended when I bring it up, even though they’re the ones that knocked on my door. Henry Spencer Lewis, in 1915, repopularized the old 17th century esoteric beliefs of Rosicrucianism (a subject itself fit for another episode or series) when he founded the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis, or AMORC, in San Jose. Inspired by old Masonic iconography and lore, as well as Hermetic legends and even Pythagoreanism, Lewis made wild and unsupported claims that Rosicrucianism, and his little San Jose order in particular, had descended directly from the priests of an Egyptian mystery cult. He took out ads in major American magazines claiming that the Pyramids of Giza had been built by Atlanteans, and he asserted that a secret chamber beneath the Sphinx containing records proving all the things he claimed would one day be discovered. One can go and visit the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum in San Jose today, owned and operated by AMORC, where in 2015, on the anniversary of AMORC’s founding, they premiered an alchemy exhibit in which visitors are led in guided meditation. Inspired in part by the writings of AMORC’s Henry Spencer Lewis, as well as the Theosophical writings of Helena Blavatsky and others, the famous clairvoyant Edgar Cayce, the so-called “sleeping prophet,” who made his pronouncements while supposedly in a trance state, also spread such claims about Egypt and the pyramids. He claimed to have been an Egyptian priest in a past life, and that the wonders of ancient Egypt were the work of biblical giants. Besides this old myth, he repeated pyramidological claims about the openings of the Great Pyramid being meant to align with stars and that future events could be foretold by examining its measurements and dimensions. From Ignatius Donnelly he took the notion that the Pyramids were built by Atlanteans, and from Blavatsky, he took the notion that these giant Atlanteans were a “root race,” and from AMORC’s Henry Spencer Lewis he took the notion that these Atlanteans had hidden the evidence of their handiwork beneath the Sphinx in a “record house.” During the course of his trance, when he was supposedly channeling knowledge directly from what theosophists call the Akashic record, the repository of all knowledge, accessible only mentally, Cayce gave indications that he was only regurgitating ideas from his voracious occult reading, even letting slip the sources of his pronouncements by explicitly mentioning them, which should be enough to show that he was neither a prophet nor really asleep during these sessions.

Yet Edgar Cayce’s influence on fringe pseudohistory today is immense. Many notions about Atlantis, its location, its influence on other cultures, and its advanced technology, its crystal death rays and whatnot, came from this fake psychic grifter, and other grifters who make claims about Atlantis and ancient aliens today have relied heavily on this fraud. For example, in his recent Netflix series, Graham Hancock, perhaps the most prolific and influential of lost civilization theorists today, spent a great deal of time ginning up evidence for the existence of Atlantis in Bimini, in the Bahamas, the very place where Edgar Cayce claimed the tallest mountains of Atlantis could be found. And in his book The Message of the Sphinx, he devotes an entire part, three chapters and 46 pages, to the notion originating from the Rosicrucians and Edgar Cayce that a Hall of Records may be found in some as yet undiscovered subterranean chamber there. So widespread was the belief that beneath the Sphinx an ancient hall of records would be found that when a new subterranean chamber was indeed discovered, not actually under the Sphinx’s paw but nearby enough to whet the appetites of modern followers of Cayce and the Rosicrucians and Graham Hancocks of the world, that its opening was broadcast live on television in a program hosted by Maury Povich. It was no Hall of Records, but rather the Osiris Shaft, the watery chamber with stone coffins corresponding to some of the earliest claims about tombs beneath the pyramid, in the middle of a lake, going all the way back to the writings of Herodotus, as mentioned in Part One of this series. But disappointments like this would not slow down or deter people like Graham Hancock, who has built his career on claims that “orthodox” archaeology is suppressing the truth about Egypt and the Pyramids. I received an email recently from a listener who took issue with me suggesting Graham Hancock is a “grifter” in Part One. In the next installment, Part Six and definitely the final part of this series, I will give some further reason for why the arguments of Graham Hancock appear disingenuous and why I class him among the modern day grifters who have inherited the tradition of such fraudsters as Helena Blavatsky and Edgar Cayce, whose careers show us that the real Curse of the Pharaohs is misinformation.

Cayce at his desk

Further Reading

Bates, A.W. “Dr Kahn’s Museum: Obscene Anatomy in Victorian London.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 99, no. 12, 2006, pp. 618-624. doi:10.1177/014107680609901209

Brier, Bob. Egyptomania: Our Three Thousand Year Obsession with the Land of the Pharaohs. St. Martin’s Press, 2013.

Cavendish, Richard. “Tutankhamun’s Curse?” History Today, vol. 64, no. 3, March 2014

Colavito, Jason. The Legends of the Pyramids: Myths and Misconceptions about Ancient Egypt. Red Lightning Books, 2021.

Dawson, Warren R. “Mummy as a Drug.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 21, no. 1, Nov. 1927, pp. 34-39, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2101801/.

Dolan, Maria. “The Gruesome History of Eating Corpses as Medicine.” Smithsonian Magazine, 6 May 2012, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-gruesome-history-of-eating-corpses-as-medicine-82360284/.

El-Daly, Okasha. Egyptology: The Missing Millennium; Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings. Routledge, 2016.

Hornung, Erik. The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West. Translated by David Lorton, Cornell University Press, 2001.

Lehner, Mark, and Sahi Hawass. Giza and the Pyramids: The Definitive History. University Chicago Press, 2017.

Martens, Britta. “Death as Spectacle: The Paris Morgue in Dickens and Browning.” Dickens Studies Annual, vol. 39, 2008, pp. 223–48. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44372196.