Pyramidiocy - Part Four: Egyptomania

In 1798, as Napoleon Bonaparte bided his time, waiting for the right moment to seize power, he sought to win further military victories in the name of France, and knowing the strategic importance of Egypt, it seemed the best territory to take. As one official of the East India company had famously stated, “France, in possession of Egypt, would possess the master-key to all the trading nations of the earth…. England would hold her possession in India at the mercy of France.” This was just what Napoleon hoped to accomplish, to disrupt British overseas trade, as well as to burnish his own reputation. Though he could not hope to conquer the East, he did fancy making of himself a modern day Alexander the Great, whom in his memoirs he placed “in the first rank…on account of the conception, and above all the execution, of his campaign in Asia.” After eluding a British fleet, he captured Malta, landed 35,000 troops in Egypt, and captured Alexandria within a couple days. Across the desert then he marched them, and as they came within sight of the pyramids, they faced a battle against 10 thousand fierce Mamluk horsemen of the Ottoman Empire. Napoleon is said to have told his soldiers that “from the height of these pyramids, forty centuries look down on you,” and then he formed his army into five squares, in which his men knelt and fired their muskets up at the riders, decimating them. Perhaps thirty French were killed, compared the five or six thousand Mamluks killed. Napoleon took Cairo within days, imagining himself like Alexander the Great, or a new prophet: “I saw myself founding a new religion, marching into Asia riding an elephant, a turban on my head, and in my hand the new Koran.” But the reason for the French Revolutionary government’s sending of Napoleon to Egypt was not to make him into a grand conqueror. In fact, expansion overseas was not an approved policy, and they had no desire to go to war with the Ottoman Empire. They did hope to disrupt British commerce, but they also simply wanted to keep Napoleon busy and away from France, as his popularity was growing problematic. So they came up with a cover story for their invasion. Their Egyptian campaign, they claimed, was only a science mission, intended “to enlighten the world and to obtain new treasures for science,” a sign of Revolutionary France’s devotion to Enlightenment principles. Therefore, accompanying the invading troops were 167 scholars who studied the monuments and temples of Egypt and worked to produce a series of academic publications, the Description of Egypt, that would appear over the course of twenty years in the early 19th century and drive public interest in Egyptian history and the pyramids. During the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt, one scholar discovered the Rosetta Stone, and amidst the publication of the Description of Egypt, in 1822, the French philologist Jean-François Champollion deciphered it. It was the birth of modern Egyptology proper, an academic pursuit that had only been in its infancy since the myth-perpetuating work of Athanasius Kircher. But the great, concomitant public interest in Egypt was far from purely academic. It was called Egyptomania, and it would fire the imaginations of many an artist and occultist during the 19th century.

In case I gave the impression that Egyptomania was a French phenomenon, it should be clarified that Egyptomania swept too through the English-speaking world. In the 1830s, Egyptomania drew Major General Richard Vyse to Egypt, where as I mentioned previously, he used gunpowder to gain entrance into previously inaccessible chambers beneath the Great Pyramid. Egyptology actually owes him something of a debt of gratitude for his discovery of Khufu’s name within the pyramid, which confirmed finally the association of the Great Pyramid with that pharaoh and not one of the many other candidates named in myth. However, in his published study, Operations Carried On at the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837, he also repeats Arab myths such as that the monument was built by Hermes or Surid, saying “ignorance and superstition so completely disguised tradition and facts, that it is scarcely possible to ascertain the foundations upon which they rest.” Egyptomania spread even as far as the United States, as evidenced by the Egyptian architecture and symbolism so prevalent in our iconography. Of course, this was already underway, likely because of the popularity of Freemasonry in America, but even during a period when Freemasonry was largely suppressed in the U.S. in the 1830s by the Anti-Masonic movement, we see the rise of Egyptian Revival architecture in many American buildings, and American preoccupation with Egyptian aesthetics reached their pinnacle, so to speak, with the obelisk design of the Washington Monument. Throughout the 19th century, we see myths about Egypt and scholarly Egyptology split and take separate paths, much as we saw that legitimate mathematics split from the number mysticism of Pythagoras and true chemistry diverged from alchemy, but it cannot be said that pseudoscience did not muddy the waters in those years too. And as we’ve seen time and time again, pseudoscience twists real science and fact to suit ideology. That was very much the case with Charles Piazzi Smyth, the popularizer of Pyramidology. As I described previously, his scientific seeming measurements were his way of supporting British Israelism, and also, his invention of the “pyramid inch” was part of his argument that the Imperial measurement system was superior to the metric system, since if Egyptians used something like it, it must have been better. Many of the 19th century pseudoscientists who perpetuated pyramid myths did so in order to argue in favor of biblical literalism, as we have already seen in claims that Hebrew slaves built the pyramids or that they were Joseph’s granaries or that they stood as evidence of certain Genesis traditions. One German writer, Carl von Rikart, for example, claimed Noah’s son Shem built the Pyramids, and perpetuated the idea that the shafts of the pyramid were meant to align with certain stars, like a telescope—a notion I erroneously attributed to William Herschel in the first episode, but which actually was the wrongheaded notion of his son John Herschel, right smack dab in the midst of Egyptomania. And perhaps the worst of all the pseudoscientific claims related to Egypt in this period were those related to race. Many were the ethnologists of the 19th century who speculated about racial hierarchy and measured the skulls of ancient Egyptian mummies in order to argue that modern whites must have had more in common with ancient Egyptians than did Black Africans, a racist claim that we can still see touted today. But the line between science and pseudoscience was not so well understood in those years, and even otherwise credible Egyptologists were known to reach inaccurate conclusions that would end up confusing the truth about ancient Egypt and encouraging the spread of false history.

The Inventory Stela

While excavating near the Sphinx in 1858, French archaeologist Auguste Mariette discovered a previously unknown temple dedicated to Isis. There, he discovered a tablet, or stela, on which is inscribed a list of statues, presumed to have once been housed within the temple. The tablet also states that this temple was discovered and rebuilt by Khufu. Mariette thus took the tablet to be evidence of some culture that had preceded that of the Egyptian dynasties. Since the Temple was next to the Sphinx, it appeared that this earlier people were capable of building great monuments. Other French scholars took it further. They gave this people a name, Shemsu Hor, the “Followers of Horus,” and since the tablet mentions Khufu finding the temple east of the Great Pyramid, but not his having built the pyramid, mentioning only his having afterward built one of the small Queens’ Pyramids, this once scholarly notion has contributed to claims that the major pyramids at Giza were only found by ancient Egyptians, but had been constructed by some earlier mystery culture. However, even right away the claims about the Inventory Stela, as it was called, were doubted by scholars outside of France. The name used on it to refer to Khufu does not follow known convention, and its reference to the goddess Isis appeared anachronistic, since no other references to Isis appear until a later dynasty. Today, Egyptologists recognize the Inventory Stela as a pious fraud. The temple was built in the ruins of a mortuary temple originally built with one of the Queens’ Pyramids, and the tablet appears to have been forged in order to create a false legend about the age of this later temple. Nevertheless, this fraud, which went unrecognized at first and was still stubbornly clung to by French Egyptologists for some years, would serve as what seemed to be scholarly evidence for the pseudohistorical theory that the Great Pyramid was not built by ancient Egyptians but rather by some even older mystery culture, which is a notion that stands at the heart of much pseudohistory, such as hyperdiffusionist claims about a precursor civilization that built pyramids all over the world, and identification of this theoretical civilization as Atlantis.

Hyperdiffusionist ideas have abounded for a long time and are reached by the strangest and most circuitous routes. We saw how the growth of Pythagorean number mysticism evolved into numerology and then into the idea that Pythagoreans had long ago traveled the world and designed megalithic monuments with telltale numerical puzzles built into their measurements. Numerological, or rather pyramidological claims like those of Charles Piazzi Smyth would do likewise. In the 18th century, one Jean-Pierre Paucton would try to connect pyramid measurements to longitude, and thus to the size of the Earth, and during the Egyptomania that gripped the French in the wake of the Napoleonic campaign, one member of the Egyptian Scientific Institute that Napoleon established in Cairo, named Dufeu, believed, according to my principal source for this series, Jason Colavito’s The Legends of the Pyramids, that by taking the measurements of the Great Pyramid’s interior chambers, one could find there encoded the coordinates of the places the ancient builders of the pyramid had visited, which included, surprisingly enough, the State of Oregon on the U.S. West Coast. But hyperdiffusionists need not depend on such arcane numerological arguments, for all they needed to argue that the builders of the pyramids had been to the Americas was the perfect evidence of Mesoamerican pyramids. One of the most influential early proponents of this claim was the French priest Charles-Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg, who in his 1868 book, Four Letters about Mexico, speculates about similarities between Mayan and Egyptian hieroglyphs, pantheons, and cosmologies and argues that both cultures originated in Atlantis, which was submerged due to a catastrophic pole reversal some 12,000 years ago. While no scholar of his era took de Bourbourg seriously, he had an influence on the fringe. For example, another Frenchman, Augustus le Plongeon, a photographer, together with his wife, dedicated his life to fleshing out this fake mythology, weaving the history of Freemasonry into it, and even totally making up stories, rewriting the Egyptian myth of Isis and Osiris, for example, with names of his own invention, Queen Moo and Prince Coh. And he cried vast scholarly conspiracy to cover up the truth when his claims were rejected as fictional by legitimate Egyptologists and experts on the Mayan reliefs that he claimed were his sources. But the fact that de Bourbourg and le Plongeon were recognized as cranks in their own day doesn’t mean squat in the world of pseudohistory and fringe belief. Their claims spawned the New Age beliefs of Mayanism as well as sundry other false ideas about Atlantis and ancient astronauts that continue to capture the attention of the credulous today.

Augustus le Plongeon

Of course, belief in ancient transoceanic contact with the Americas was not new. Long had there been claims about the Hebraic origins of Native Americans. And since the late 1820s, Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, had been making claims connecting the Americas and Mound Builder culture with Egyptians. He claimed they were the Lost Tribes of Israel, but their scriptures, which he claimed to translate from some golden plates an angel had revealed to him, and which he conveniently was not allowed to show others, was inscribed in what he described as “reformed Egyptian.” When a transcription of these supposed plates was shown to classical scholar Charles Anthon by one of Smith’s adherents, Anthon said he counseled the fellow not to give Smith any money, though the Mormon version of the meeting has it that Anthon confirmed the characters were Egyptian and signed a statement to that effect, only to afterward tear it up upon hearing more about their provenance. So an expert says he saw right through them, and the believers claim, conveniently without evidence, that he actually believed them genuine hieroglyphs. But why a lost Tribe of Israel would be writing in Egyptian hieroglyphs was never adequately explained. Smith would continue in his Egyptomania throughout his lifetime. When during the height of Egyptomania a travelling show came through the Mormon Mecca of Kirtland, Ohio, exhibiting a mummy and some papyri, Smith bought the manuscripts and claimed once again to have magically translated them, revealing that they were actually the writings of Abraham and Joseph. It is from this Book of Abraham that the Mormon cosmology was promulgated, which involved a slowly rotating planet near to the throne of God called Kolob. This is given as an Egyptian cosmology, again presenting Egyptians as ancient astronomers, though of course, no Egyptian hieroglyphs anywhere have ever corroborated this strange cosmology. Eventually, when legitimate Egyptologists were able to examine these papyri, they proved to be rather typical funerary texts. Nevertheless, as the basis of their religion relied on the notion of ancient transoceanic contact from the Near East, the Mormon Church would continue to amplify pseudohistory like that of de Bourbourg and le Plongeon whenever it appeared, as would others promoting alternative world histories, like the man sometimes credited as the father of modern catastrophism and alternative history, or pseudohistory as it should rightly be called: Ignatius Donnelly.

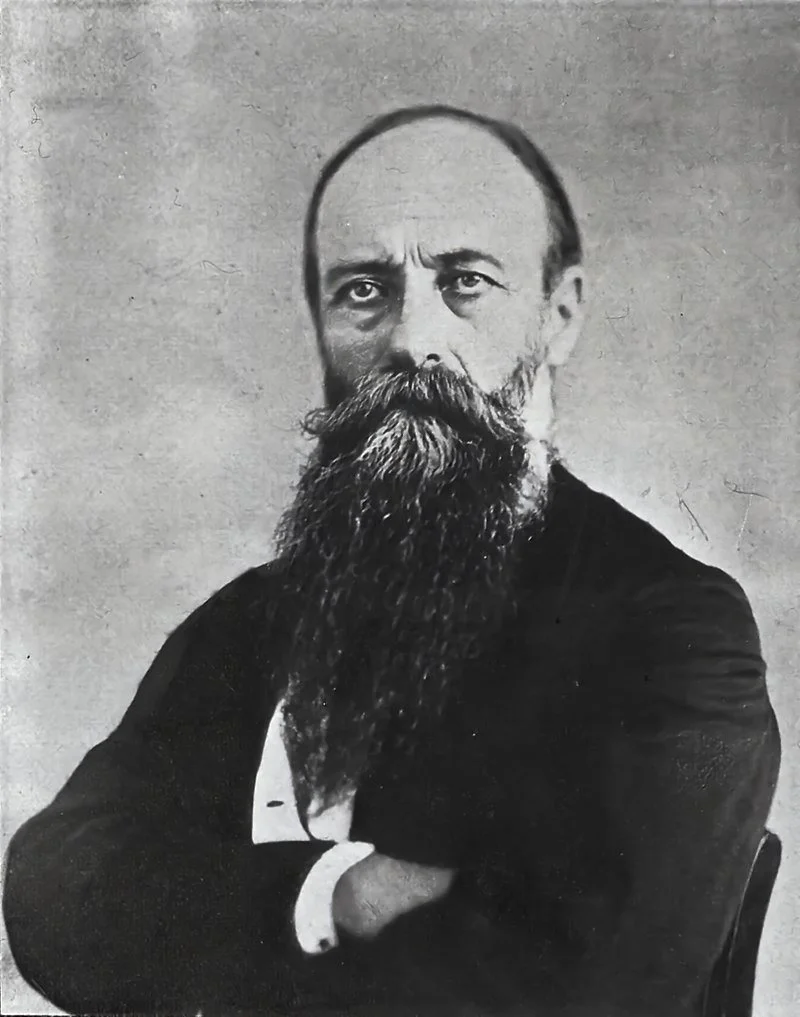

Donnelly has come up recently, in my series on Shakespeare denialism, because of his publication of The Great Cryptogram, arguing that Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare and left clues to prove it in the form of an elaborate cipher embedded within Shakespeare’s works. That wasn’t the only work of paranoid fantasy that Donnelly wrote and passed off to the world as scholarship. Not only credited as the father of fringe history, but also the father of American Populism, he’d had a long career railing against the corruption and decadence of the Gilded Age as a lieutenant governor in Minnesota, a three-term congressman, and a vice presidential candidate in the People’s Party. Already paranoiac in his politics, he saw political corruption everywhere and claimed that a “vast conspiracy against mankind has been organized on two continents and is taking possession of the world.” After leaving politics, he aimed that paranoia at historical research, but he had studied law, not history. He was an auto-didact, completely self-taught, and like many such people drawn to the field of history, he gravitated toward the most sensational subjects and used a simpleton’s logic to assert completely false claims. He would have been a great YouTuber and podcaster today. He took Plato’s allegory about Atlantis as fact, and he synthesized it with biblical literalism to create a mish mash legend that even today enthralls those who mistake his work for legitimate historical research. Rather than concluding the obvious, that Plato was mythmaking within the established tradition of flood narratives, Donnelly said that Atlantis had been the geographical setting of Genesis, the location of the Garden of Eden, and thus its sinking had been the very same event as the flood of Noah. He borrowed liberally from de Bourbourg and le Plongeon, claiming falsely that Mayan hieroglyphs contained elements of Egyptian hieroglyphs and even Greek, and arguing that there was no possible way that Mesoamerican cultures and ancient Egyptians could have imagined the same pyramidal structures independently, and so this unique architecture must have come from a progenitor culture, the Atlanteans. Of course, as Colavito points out convincingly, pyramidal structures arise naturally, such as when sand is poured into a pile, and really, before more advanced building techniques involving internal frame structures were developed, a tapering shape was the only possible way to build something tall like these monuments. Donnelly was just profoundly wrong, and would go on to be very wrong time and time again, such as when he invented catastrophism in his second book, Ragnarok, which would greatly influence the more modern catastrophist and chronological revisionist Immanuel Velikovsky in his own pseudohistorical, pseudoscientific wrongness.

Ignatius Donnelly in 1898.

Egyptomania was not limited to scholars and pseudoscholars, however. It was also rampant among the literati. Among Romantic poets, Egypt was an especially favorite subject, as were the Arab legends about it that had been transmitted to them. The same year as Napoleon’s campaign, Walter Savage Landor reworked a legend about an Iberian invader falling in love with an Egyptian queen in the long poem Gebir, and this work would inspire many 19th century writers who would themselves write works with an “Orientalist” theme. Robert Southey in Thalaba the Destroyer, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge in “Kubla Khan” demonstrate this influence, but the most relevant to Egypt would again be Shelley’s “Ozymandias.” But Orientalism and Egyptomania emerged in fiction within a different genre: horror. While many of the staples of Egyptian horror tales can be traced back to the story of Setna, with its ghosts and curses, and the story of Surid, with its booby traps and monster haunted subterranean catacombs, the very first story involving a reanimated mummy appeared in 1827, in a science fiction novel called The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century, in which galvanic shock is used to revivify Khufu in very Frankenstein fashion, who then goes on to give sage advice. In the ensuing years, many very famous authors wrote mummy stories. Edgar Allan Poe wrote a satire called “Some Words with a Mummy,” and afterward mummy stories became horror stories, with Louisa May Alcott of Little Women fame writing the first story involving a mummy’s curse, called “Lost in a Pyramid,” and Jane Austen following suit with her own mummy’s revenge story, called “After Three Thousand Years.” Arthur Conan Doyle, inventor of Sherlock Holmes, would eventually get in on the trend too, as would Dracula creator Bram Stoker. But some artists of the era would move beyond the Orientalist themes of Egyptomania and take an interest in the old pyramid legends, which had carried over into the occult. For example, Éliphas Lévi, better known today as an occult magician than a poet, was a 19th century French esotericist and former Catholic seminary student. He devoted his life to writing about the occult, and within his can be found many pyramid myths as transmitted to him through the Hermetic traditions that he helped to spread to a new generation. Likewise, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle did not just write a simple mummy story; he wrote about a mummy preserved in a deathless sleep by an alchemical elixir, who was resurrected by the titular talisman, “The Ring of Thoth.” Doyle was also a convert to that other great 19th-century occult belief, spiritualism, the notion that the souls of the dead could communicate with the living through mediums in a séance. And there was one major spiritualist figure, Madame Blavatsky, who, inspired by the occult writings of Éliphas Lévi and others, would establish her own branch of occult “science,” called Theosophy, and would promote and reinvent numerous pyramid myths.

Helena Blavatsky, whom I’ve had occasion to talk about before in relation to the religious dimension of UFO belief, was a Ukrainian woman who, after leaving her aristocrat husband, apparently traveled a great deal in Europe and elsewhere. Many are the tales about her travels before she eventually settled in the US, with claims about her performing as a concert pianist and riding horses in a circus. Stories she told herself had her traveling much further afield, to Nepal, India, and Egypt. She would eventually claim that she had been tutored by so called “hidden masters,” interdimensional sages who schooled her in the secret histories of the world. In New York, she was a practicing medium, and she attracted the interest of one Henry Steel Olcott, a spiritualist with an interest in the occult. The two of them would go on to found the Theosophical Society, dedicated to establishing a universal brotherhood, to encouraging the comparative study of religion, philosophy, and science, and to investigating the unexplained and humanity’s supposed paranormal powers. She published her first book, Isis Unveiled, which presented itself as a “master-key” to all knowledge and mysteries, achieved through ancient wisdom. It is hard to overstate the influence of Blavatsky and Olcott and their Theosophical Society. They traveled to India and were extremely influential on Mahondas Gandhi and helped bring about a Buddhist revival throughout the Indian subcontinent. It is thanks to their journeys of religious and philosophical awakening that India became a place for pilgrims to go in search of enlightenment and Americans came to believe in the wisdom of Eastern gurus. But Blavatsky is widely remembered today as a total fraud. Her book, it turned out, was a patchwritten hodgepodge of occult texts she had plagiarized. Arthur Conan Doyle said it “was edited rather than written by her…that a hundred books were used for its production, and that when the unacknowledged quotations are taken out there is practically nothing left.” Moreover, she was revealed by the London Society for Psychical Research to be a fraud, engaging in fake parlor tricks as a medium, as indeed, most or all mediums did, and forging letters from her supposed “hidden masters” in order to fake their existence. Nevertheless, Theosophy survives today, and Blavatsky’s claims about progenitor civilizations remain as popular as ever. In Isis Unveiled and especially her later work, The Secret Doctrine, Blavatsky laid out her conception of the secret history of mankind, which she claimed extended back much further into the benighted past than historians allowed. She traced history back through several “Root Races,” beginning with beings of pure spirit. Subsequent, physical iterations of mankind had their time, each on some lost and mythical continent, beginning with Hyperborea, followed by Lemuria, and then Atlantis, and she claimed that vestiges of Atlantean monuments remained, in Stonehenge and the pyramids at Egypt. She imagined Atlanteans to be giants who mated with “she-animals” to produce primates—a weird reimagining of the story of the Watchers and the Nephilim. To buttress her claims, she made reference to the work of the pseudohistorian Augustus Le Plongeon, claiming against all contrary scholarship that the Mayan and Egyptian civilizations were one and the same, remnants of Atlantis. Later Theosophists would even claim that these Atlanteans were one and the same as the Followers of Horus, the Egyptian precursor culture that had been imagined because of the fraudulent Inventory Stela. Blavatsky was a grifter who took the myths and fake histories about the ancient past that came before her and remixed them as a new revelation, making of herself a sage master when she was little more than a liar and cult leader. And in doing so she set the stage for the final modern chapter of pyramid myths, when falsehoods are more and more purposely spread and grifters like her abound.

Helena Blavatsky, circa 1877.

Until next time, remember, all legitimate sciences and academic fields have some embarrassing episodes in their pasts, having developed in periods of backward thinking and prejudice. The sign of a true science is how successfully it has extricated itself from its own ignorant past.

Further Reading

Brier, Bob. Egyptomania: Our Three Thousand Year Obsession with the Land of the Pharaohs. St. Martin’s Press, 2013.

Colavito, Jason. The Legends of the Pyramids: Myths and Misconceptions about Ancient Egypt. Red Lightning Books, 2021.

El-Daly, Okasha. Egyptology: The Missing Millennium; Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings. Routledge, 2016.

Hornung, Erik. The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West. Translated by David Lorton, Cornell University Press, 2001.

Lehner, Mark, and Sahi Hawass. Giza and the Pyramids: The Definitive History. University Chicago Press, 2017.