The Myth of the Thuggee Cult

In American culture, the meaning of the term “thug” varies depending on your background and the cultural context. By its modern dictionary definition, the word refers to violent criminals, or some kind of vicious ruffian, but among many who identify with urban street life and Black hip-hop culture, the term has taken on a different meaning, reflecting the idea that systemic racism creates gang culture. This use of the term was championed by rapper Tupac Shakur, who touted a “Thug Life” as a kind of determined response to the setbacks and obstacles that the disadvantaged face. For Tupac, “Thug” was an acronym deriving from “The Hate U Give,” referring to the idea that so-called thugs are created by hate and inequality, and that their very existence is an inspiring show of resilience in the face of great adversity. Interestingly, the word “Thug” entered the English language from Hindi, where likewise it referred to a subculture of violent criminals viewed as a savage threat by English colonizers but viewed quite differently in many Indian villages. The Thug, those who perpetrated a class of crime called Thuggee, would become legendary, not just in India where, during the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th, their crimes were perpetrated, but across the Western world, where the word Thug could hardly be spoken without a shudder. The crimes of the Thuggee became well-known after English authorities in India undertook the task of wiping them out, when the world learned that they were not just bands of highway robbers, but actually a murderous sect that put to death every person they robbed, leaving none behind to witness against them, not even women or children. More than just ragtag gangs of bandits, they were an organized conspiracy that acted as one, it was said, controlled by some central authority. And not just thieves with a bloodlust, they were a cult, it was claimed, devoted to Kali, the goddess of destruction. It was explained that they strangled all their victims so as not to spill their blood but would afterward mutilate their corpses in their evil sacrificial rituals. On the lawless roads of India, it was said that Thuggee claimed the lives of 40,000 innocent travelers every year, until the 1830s, when British authorities began to stamp them out. But even after their suppression, the Thugs of India would loom large over European and American imaginations. They became the fabled villains of many a work of fiction, and their name entered the lexicon, such that even today we talk about “thuggery” as a class of criminal behavior. And just as today hip-hop culture suggests that thugs are misunderstood or misrepresented, so too revisionist historians have looked skeptically back on the idea of Thuggee in India and suggested that it may have been a colonial construction, an exaggeration or misrepresentation exploited by colonizers to seize greater control of India. This revisionist view even goes so far as to suggest, in some arguments, that Thugs did not really exist, that Thuggee was only ever a lie promoted by the British.

*

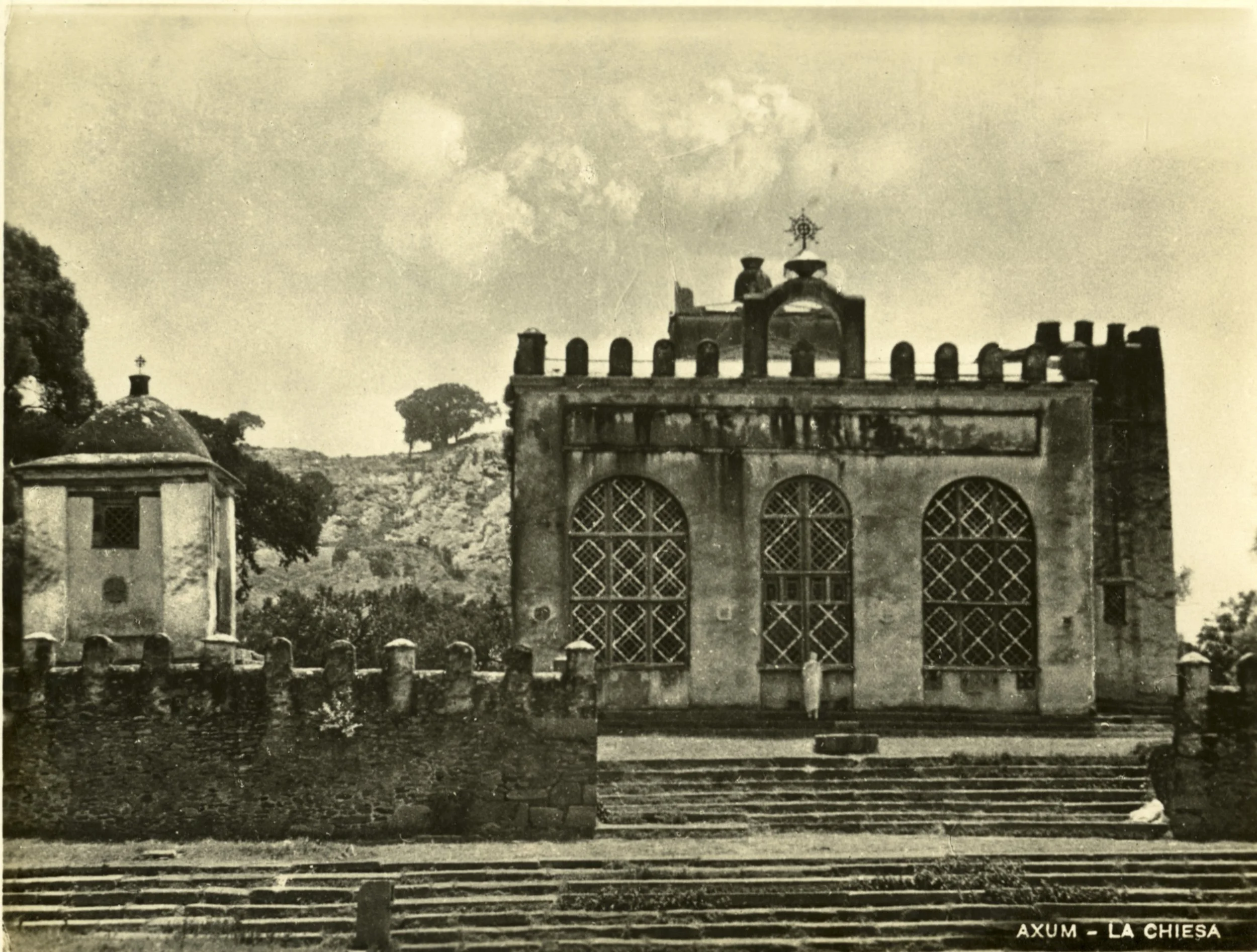

I am once again exploring a topic from the Indiana Jones film franchise in my quest to immerse myself in the real history and folklore behind the films ahead of what is likely the last film in the series this summer. When it comes to Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, the sequel to the 1981 film Raiders of the Lost Ark, which is actually a prequel, the macguffin itself, the Sankara Stones, are rather light on actual historical background, and at first I didn’t think I would make a full episode having to do with Temple of Doom, beyond perhaps a patron exclusive minisode. But that was before I started looking into depictions of India and Indian culture in the film. I was inspired to take a second look at the film because my wife, who is Indian by way of Fiji, has spoken more than once about how this film, which incidentally she loves, caused her some grief growing up in California because of its totally incorrect depiction of Indian culture. Specifically, she says that other kids would ask her if, because she is Indian, she eats monkey brains. This of course refers to the famous dinner scene in which Indy and his companions are disgusted by a dinner of live snakes and beetles, soup floating with eyeballs, and chilled monkey brains eaten directly out of the skull for dessert. Obviously the scene serves only as comic relief in the film, but a 2001 study conducted by the University of Texas does indicate that, as my wife experienced, a majority of Americans believed it to be an accurate portrayal of Indian cuisine. In fact, there is no historical evidence of such foods being eaten in India. Nor was my wife the only Indian to be troubled by this depiction, as the film was initially banned in India because of its misrepresentation of Indian culture, specifically because of the dinner scene. But as I looked further into the cultural representation in the film, a much larger problem revealed itself: that of the Thuggee cultists who served as the film’s villains. As indicated, there is historical debate over the very existence of such a group. I struggled a bit to access the research materials I needed to make this episode, but I was helped out by friend of the show Mike Dash, whose work on such topics as the missing lighthouse keepers of Eilean Mor, the Devil’s Footprints, and Spring-Heeled Jack I have relied on before, and whom I interviewed for the podcast some years ago. Mike Dash wrote an exhaustively researched book on this topic, Thug: the True Story of India’s Murderous Cult, and when I couldn’t get a copy in time, he generously sent me the galleys of the book. I really recommend listeners interested in this topic check it out for themselves. It is a fascinating read, and that is why it’s somewhat unsurprising that Steven Spielberg and George Lucas chose to feature the Thugs of India as the bogeymen of Indy’s second outing: they are and have long been a fascinating and terror-inducing group. Ever since the early 19th-century novel about them, Confessions of a Thug, appeared in 1839, they became a mainstay villain of literature. They appeared in the popular French novel, The Wandering Jew, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, even featured them in a story. Most notably, a series of swashbuckling stories by Italian novelist Emilio Salgari cemented them as apt villains for an adventure tale. Into the 20th century, they continued to crop up in novels and were featured in numerous films, including the 1939 adventure film Gunga Din, in which characters discovered that the Thugee cult was still active even long after its supposed suppression. It is this film that appears to have inspired their use as villains in Temple of Doom, but really, if the filmmakers were looking for a villain in India as iconic as the Nazis in Europe, then Thugs were the obvious choice. But to what degree were the filmmakers, knowingly or unknowingly, perpetuating a historical myth?

The poster for Gunga Din

First, we must understand the context in which a Thuggee cult supposedly operated, which means a few words about India and the establishment of British imperial interests there. Before the rise of British power in India, the last great dynasty was that of the Mughals, Muslim rulers who built an empire of such wealth and grandeur that it grew to be too much for lesser rulers to handle. The last of the great Mughal emperors was Aurangzeb, and after his passing in 1707, the Mughal Empire disintegrated into a patchwork of rival princedoms, with the governors of rich provinces ruling as independent monarchs, paying only lip service to later Mughal emperors. This chaotic state of affairs was further complicated by the conquests of bellicose Hindu tribes from Central India called Marathas who began seizing territories for themselves. At this time, the merchants of the British East India Company, who had established themselves over the preceding centuries as buyers of spices and other goods and had establishecd a network of warehouses and forts across India, began to view all these recent civil wars as bad for business. With muskets and artillery at their command, they realized they could subdue the subcontinent and improve their bottom line, which they set about doing, taking possession of city after city and establishing themselves as an imperial power. In 1784, parliament passed the India Act, placing company directors under government supervision, and thereby nationalizing the entire colonial venture. Thus the British came to rule numerous cities and regions of India, collecting taxes and charging exorbitant rents of area villagers and essentially monetizing the populace. It was in one such town in northern India, Etawah, about 300 kilometers southeast of Delhi, that the British first caught wind of the dreaded Thug menace. Thomas Perry, a British Magistrate struggling to bring order to the lawless area, began to receive reports of corpses being discovered in wells and roadside pits. It was a mystery that he seemed unable to solve. He knew that there were highway robbers in the area, as there were on the roads throughout India, but this was unprecedented. These murderers seemed to be mutilating and hiding corpses, and leaving no one alive, for no witnesses could ever be found, and the bodies themselves, assumed to be those of travelers, could not be identified locally. The horrifying conclusion was that some band of prolific killers resided nearby, or even among them.

Perry and other British, as well as the Indian people they had essentially conquered, were perfectly familiar with the threat of banditry. As Mike Dash points out in his book, some of the earliest of Indian texts, such as the Sanskrit hymns the Vedas, which are some 3000 years old at least, portray a certain Hindu deity, Rudra, as the lord of all highway robbers. And in one of the first accounts written by a foreign visitor to India, that of the 7th-century Buddhist monk Xuanzang, we see a traveler nearly being killed by pirates who haunt the rivers. British merchants reported in the 1600s that they could not travel with their goods on the roads without a large contingent of armed men because the country was “so full of outlaws and thieves that a man cannot stir out of doors without great forces.” The kinds of highwaymen that they were accustomed to, however, did not murder entire parties and hide the bodies like this. There were, though, organized bands of thieves who would not shrink from murder called dacoits. These gangs of robbers typically attacked their victims in town, however. They would target a rich man and fall upon his house without warning, invading his home and terrorizing all the residents and servants within. Indeed, dacoits were active in the area around Etawah, and an increase in banditry could be blamed on the British themselves. There was a region nearby, the Chambal, a maze of ravines that was difficult to navigate unless you were native to the area, and the men of the Chambal had long worked as soldiers for hire because the land of the Chambal did not support much agriculture. With the coming of East India Company, though, who refused to hire them as mercenary soldiers, they had little choice but to turn to highway robbery and to join dacoit gangs to support their families. But like most highwaymen, these dacoits did not typically set out to murder. They used fear, and when they were forced to attack those who did not cooperate with their robbery, they aimed to injure rather than kill. Indeed, dacoity was considered an honest profession by many, as dacoits served as a kind of informal militia for some villages, and they tended to rob the rich and share with the poor. As Thomas Perry looked into the murders occurring in his territory, he was quite certain that they were not being committed by run-of-the-mill highwaymen or dacoit gangs. And eventually, he confirmed this conviction when some of the murderers were arrested and confessed, identifying themselves not as dacoits but as Thugs.

A family of dacoits

Through Perry’s investigation and the confession of captured Thugs, as well as through the numerous East India Company records of later prosecutions, we can know a great deal about the practices of the Thugs. Unlike dacoits or other highway robbers, they worked in absolute secrecy. As already established, they left no one alive to witness against them, but they did not fall on their prey like a raiding party. Rather, they insinuated themselves, just a few at a time, into the travelling parties they targeted, convincing their marks that they were friendly and trustworthy fellow travelers and that it would be best for them to travel together to reduce the chances of highway robbery. This is one part of the horrific practices of the Thug, that they befriended and traveled with their victims, sometimes for days and weeks, always intending to murder them all when they could steer them toward an out-of-the-way location, at which time the rest of their band, which might be trailing behind on the road or even riding in advance, would converge to share the spoils. First, however, came their other horrible practice, the murder itself. Thuggee bands distinguished themselves again from other bandits in the methods of their violence, which were equally as intimate as their inveigling of targets: they strangled their victims to death. There were men among them whose specific job it was to do the strangling, cold-blooded killers who sometimes used nooses or special garrotes, but as these could easily identify a strangler, most instead began using scarves with a knot tied in it that could be used to mercilessly tighten it around a victims throat with a twist. Some wrapped a coin in their scarves that proved effective at crushing windpipes. These stranglers were callous executioners, murdering entire retinues and convoys full of people, whole families, men, women, and children, though sometimes a child would be kept alive and raised to become a Thug themselves. Strangely, they did not shrink from stabbing and cutting open their victims before burying them, but they only did this after they had strangled them to death, and this practice would be the cause of some myths about Thuggee, as will be seen. But the Thuggee were already, even among themselves, it seems, surrounded by myth. It became clear during the earliest investigations that Thuggee gangs had been operating beneath the nose of the East India Company for many years without their even being aware of the group’s existence. According to the oral traditions of the Thugs themselves, given under interrogation in later campaigns against them when many turned King’s evidence against their fellows, Thuggee tribes had existed since great antiquity, all the way back to the time of Alexander the Great, and they claimed to be descended from Muslim families of a high caste. However, the word “thug” does not appear to have been used to refer to murderers before the 1600s, and other traditions trace Thug tribes to 16th-century Delhi, when a clan was exiled by the Mughal Emperor for killing one of his slaves. Other ideas were that the practice of Thuggee started among destitute Mughal army soldiers, or among poor herdsmen driving cattle on the roads. In short, Thugs did not themselves agree on the origin of their way of life, but some of their boasts about their ancient heritage, and some of the consistent practices among even distant bands, such as their secret communication by coded phrases and signs, and their very particular murder rituals, fed into later claims that they were an ancient secret society, a murderous cult operating as one, its crimes coordinated by some sinister overseer.

The first of the campaigns against Thuggee gangs began in the Chambal ravine country, as British forces commanded by Magistrate Perry’s assistant followed some leads to that area, where they ended up being first poisoned by local villagers and then ambushed by Thugs in the ravines. Concerned about an all-out rebellion against their government, the British returned with artillery and leveled the Thug stronghold in the area. For several years, then, the British approach to Thugs was just to pursue them if they plied their grisly trade too close to British-controlled towns and cities. This seemed amenable to Thugs, who were travelers by nature and simply began murdering farther afield, on roads where it was safe to operate without rousing the ire of the British. However, the view of the threat they posed changed over the next several years as British citizens more and more became the victims of these highway killers, and as Thugs chose to target many soldiers-for-hire who had sold their service to the British, not so much because of who they served as because they were a perfect target when they took their leave and traveled home with all their back pay on their person. And when the Thugs began robbing the treasure parties of powerful Indian bankers, all tides finally turned against them. British Company men began pursuing and trying Thugs regardless of where they were operating, and one officer, William Sleeman, an ambitious man, saw in the hunt for Thugs the cause of a lifetime. He felt strongly about the evil of Thuggee and believed wiping them out entirely would be a boon to the Indian people, but he also saw that he could make a name for himself doing it and earn a comfortable political position. He threw himself into the campaign with religious fervor, greatly relying on a tactic he had seen was working elsewhere, that of turning captured Thugs into informers, or what were called “approvers.” This was somewhat necessary, since by the very nature of their crimes, Thugs did not leave witnesses alive. By promising that Thugs who turned King’s evidence could keep their lives, he found many eager to cooperate in identifying other Thugs. As he developed his tactics in 1829 and 1830, Sleeman jailed hundreds of alleged Thugs, but his suppression of Thuggee did not kick into high gear until he pursued and captured an influential young Thug leader named Feringeea, who had been raised a Thug and knew everything about how they worked. With Feringeea as his principal approver, Sleeman was able to identify and arrest more than 700 Thugs in 1831 and 1832, and more than that, Feringeea was able to predict the movements of Thug gangs like no other informant before him. By the mid-1830s, with Feringeea’s help, Sleeman had produced charts marking known Thug routes as well as their favorite places to dump bodies. And more than that, he had mapped the homes of all identified Thugs and, believing based on the confessions of Feringeea and other approvers that Thuggee was a hereditary profession, he compiled genealogies in order to identify and arrest Thugs simply for familial association. We begin to see here the potential for egregious miscarriages of justice.

An 1857 drawing in the Illustrated London News depicting Thugs and other classes of Indian criminals

It is easy to take the side of the British in this story, as on the surface, they are pursuing and bringing to justice bands of brutal murderers. But of course, we should also look at the entire imperial presence of the British in India as morally and philosophically wrong, and thus any law enforcement campaign of theirs, administered as it was on their unwilling subjects, as being inherently unethical. And that is the lure of historical revisionist views of the Thuggee, some of which deny Thuggee’s existence altogether and see it as a kind of witch hunt used as an excuse by the British to brutally crack down on those they had imperially dominated. From a postcolonial view, it is a tempting position to take, and it certainly illustrates well the true evils of imperialism. Indeed, revisionist historians are not even the originators of this view, as in the beginning of anti-Thug campaigns, even many British in India were skeptical, finding it hard to believe that such a mighty evil as Thuggee could possibly have been at work right beneath their noses for years without them knowing it. And just as historical revisionists focus on Sleeman’s reliance on the testimony of approvers, approver testimony was viewed as unreliable hearsay by many even at the time, and in the beginning, Thugs were usually acquitted simply because they categorically denied what approvers said about them. Much of what critics point out is absolutely accurate. The motives of approvers should be questioned. They turned King’s evidence to save their own necks, and they knew that, to receive clemency, they would need to provide what Sleeman was looking for, and that might have meant telling him what he wanted to hear. Moreover, there certainly were miscarriages of justice. Innocent and guilty alike were arrested in the sweeping anti-Thug campaigns of the 1830s. Sleeman’s genealogies of Thug families included men who had chosen not to become Thugs like others in their families, so certainly many innocents were detained. And he served warrants and prosecuted suspected Thugs based on hearsay evidence from known criminals with reliability problems. There is the clear possibility that approvers simply accused innocents of Thuggee because they had some personal ax to grind with them, much as in a witch hunt. All of this is true, but it does not amount to the British inventing the entire phenomenon.

Company records, which Mike Dash researched exhaustively, reflect that great care was actually taken to marshall convincing evidence due to the very fact that Sleeman had to overcome skepticism about Thuggee. His approvers must have been giving mostly reliable information, and there are a few indications. First, they viewed turning King’s evidence as a valid change in career path; just as previously they viewed Thuggee as a legitimate occupation, changing their allegiance to serve the British was viewed as just a change in profession, nothing dishonorable about it. Many, like Feringeea, appeared earnest and eager to serve Sleeman to the best of their abilities. And the threat of losing their privileges, or even losing their lives, hung over them if they were caught lying. Also, we know that they provided accurate information in most regards, as their depositions led to hard evidence. They routinely led Sleeman to the places where they and others had hidden bodies and helped exhume the remains of these victims to be identified. Likewise when they fingered fellow Thugs, stolen loot was frequently recovered from those they identified, confirming that they were indeed involved with Thug murders. Furthermore, as Mike Dash shows in his research, Sleeman and others did not trust approver accusations blindly; they pitted approvers against each other, cross-examining them to ensure their claims could be believed, and having each of them pick suspects out of line-ups, or identity parades as the British call them. And whatever we might say about the ethics and fairness of the British, their tactics certainly worked, for Thug murders plummeted amid the anti-Thug campaigns. Some historical revisionists who claim that there never were any Thugs, that the whole thing was made up as a cudgel to keep the Indian people down, might say the reduction of Thug crimes was a further lie, but their position is simply insupportable. Thuggee gangs certainly existed. The British were not alone in pursuing them, as Indian bankers had also undertaken anti-Thug campaigns. These bands of stranglers left a wake of bodies behind them, and the records of the East India Company attest to the discovery of these corpses even before the threat of Thuggee was properly identified. And early reports about and investigations into these highway murders demonstrate that this was no conspiratorial lie spread by the East India Company. The Thugs of the Chambal ravines were viewed as a local threat at first, but unbeknownst to Magistrate Perry at the time, about a thousand miles away to the south, near Madras or what is today Chennai situated on the Bay of Bengal, another Company administrator had been recording his own struggles to bring a tribe of highway murderers to justice, these called Phansigars, or “stranglers.” But while the existence of Thuggee stranglers cannot be denied, their nature was certainly misrepresented, and while Sleeman’s practices in bringing them to justice may have been effective, though unethical and imperfect, he certainly was responsible for the creation of the lasting myth of a Thuggee cult.

As William Sleeman waded through so many approver depositions and testimonies, learning all he could about Thuggee methods, including their customs and their beliefs, he latched onto frequent mentions of the goddess Kali as being protector of Thugs, and he developed a notion that Thug bands were not actually thieves, that their looting of corpses was an afterthought, and that in fact they were sacrificing their victims to Kali. In his mind, this explained why they did not shed blood until after they had strangled their victims, because they intended to offer that blood to Kali, thus the post-mortem stabbing and mutilation of corpses. This seed of an idea grew in his mind, added to with further speculation, until he imagined that all Thugs across the subcontinent served some central Thug priesthood, funneling money from their highway robberies to a certain temple that he believed was their headquarters. This notion was almost certainly engendered by the typical Christian British view of Hinduism as a barbaric religion. Many were the misconceptions about Hinduism among the British, who believed false claims that Hindu sacred texts actually encouraged some of the terrible things they heard about Indian customs, such as the murder of unwanted infant daughters, the sacrifice of children, and the practice of suttee, in which widows were thrown onto their husbands’ funeral pyres. In fact, these practices were uncommon, if they existed at all, and were forbidden by the tenets of the Hindu faith. But British could not get over their view of the Other as savage and backward. Every year they saw Hindus pushing massive wooden carts carrying gargantuan statues of Hindu deities to a temple in Puri on the Bay of Bengal dedicated to the god Jagganath, and often some faithful were crushed to death beneath the huge wheels of these wagons. Indeed these massive Jagganath wagons that rolled right over people are where we derive the English word “juggernaut.” The British learned of these deaths, and saw the sun-bleached bones that lined the roads to this temple, and believed that Hinduism encouraged a religious madness, murder, and suicide. In fact, the bones on the road were those of the terminally ill people who had died making pilgrimage to the temple, and crushing deaths beneath the wheels of juggernaut carts were rare and accidental. But the British came to view Hinduism as a death cult, and Kali, who is depicted with blood on her hands and a blood-drenched sword, wearing a necklace of severed heads, was the most horrifying aspect of the religion. Thus it is not that surprising that William Sleeman would latch onto mention of Kali by his approvers and invent this dark and horrifying backstory for the Thugs he pursued.

It seems, however, that William Sleeman was so steeped in the massive files and endless records he was keeping that he simply could not see the forest for the trees. Study of his own records, undertaken by scholars like Mike Dash and another academic whose work I’ve relied on, Kim Wagner, demonstrate that religious belief was not central to Thuggee culture. Certainly Thug approvers mentioned their belief that Kali protected them, but this was little more than common folklore. In fact, many Hindus thought of Kali as a protector, and that belief was especially common among criminals of all stripes. Nor was this the only kind of superstitious belief common among the Thugs, who put great stock in portents and omens that had nothing to do with Kali or Hinduism, such as believing that the movements or cries of certain wild animals, like owls, may mean bad luck, necessitating a change in plans. The Thugs had no official religious texts, no uniform ritual of worship; in fact, there was great religious variety among them, as some were Hindu but others were Muslim and Sikh. It is possible that some of Sleeman’s approvers emphasized the Thuggee connection to Kali as a kind of excuse for their murders, to suggest it was Kali who really killed, and not them, but the bulk of all testimony makes it abundantly clear that they killed in order to rob and leave no witnesses. There was even among the many confessions of Thugs a clear reason given for why they strangled and only afterward stabbed and mutilated corpses. In the Mughal empire, under Islamic law, murder by strangulation did not incur the death penalty, thus they likely strangled just so that they wouldn’t be put to death if caught. Afterward, they stabbed only to make sure their victims were dead, or in some cases, they disemboweled in order to minimize bloating during decomposition, which often caused the soil of the shallow mass graves they used to rise, revealing the hiding places of bodies. But even though Sleeman’s speculations about a Thuggee cult could be refuted by his own research, he became the mouth of the anti-Thug campaign and spread these rumors. He sent anonymous letters to the Calcutta Gazette, published as a series called “Conversations with Thugs,” and in it he promulgated his view of the Thugs as a vast secret religious society devoted to performing blood sacrifices to Kali. Soon his version of the criminal band was generally accepted among the British, and the 1839 novel Confessions of a Thug, inspired by Sleeman’s accounts and depicting Thugs as being somehow both Muslim and devotees of a Hindu goddess, became a bestseller in Britain. Thus the myth of the Thuggee blood cult, brought so vividly to life in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, was born.

Image falsely depicting Thuggee as a cult of Kali.

By 1840, the practice of Thuggee had effectively been wiped out by the aggressive policing and prosecution of William Sleeman and other Company administrators. But there would always be rumors that some Thug enclaves, perhaps in the foothills of the Himilayas, had evaded capture. This is what served as the core notion of adventure films like Gunga Din and Temple of Doom, the idea that, after its supposed suppression, the cult had survived and remained secretly active. It is not unlike fiction in which escaped Nazis scheme to bring about a Fourth Reich in the 1970s, like the novel and film The Boys from Brazil, or the current streaming series Hunters. In truth, there are records that indicate some Thugs escaped the anti-Thug campaigns, but since Thuggee was not a cult that might grow in secret and rise again but rather an occupation resorted to due to socio-political and economic circumstances, when it was no longer safe nor profitable to practice Thuggee, former Thugs just went into other work, becoming soldiers-for-hire or even merchants. The real mystery that remains is not whether they survived their suppression, but how many victims they claimed. William Sleeman’s grandson published a book about a hundred years after the anti-Thug campaigns called Thug, or a Million Murders, in which he asserted that Thuggee claimed in the neighborhood of 40,000 lives a year, and since he believed the claims that Thuggee had been practiced since the 13th century, he claimed it must have been responsible for something like 20 million murders. Mike Dash, however, is skeptical. Pointing out that Thugs may not have really existed, as such, so long before the British noticed their trail of dead, and further pointing out that their activities were seasonal, only undertaken in the cold season, and that Thug confessions were extremely inconsistent vis-à-vis the number of dead, that they were possibly inflating numbers out of braggadocio or to please their captors, Dash estimates a far more conservative fifty to one hundred thousand victims… and yet this too is staggering and stomach-turning. In the end, we find multiple layers of false history surrounding the Thugs of the Temple of Doom. They were misrepresented by the British at the time in such a way as to mischaracterize and defame Indian culture generally, representing it as a cesspool of evil pagan blood cults, and then the historical reality of Thuggee was erased by revisionist historians who sought to use them as an example of the evils of imperialism, which of course can be easily demonstrated without resorting to historical negationism. And in between, they were made into the nefarious villains of a blockbuster eighties adventure film whose depictions of Indian culture should rightly cause us to cringe today.

Further Reading

Dash, Mike. Thug: The True Story of India's Murderous Cult. Granta Books, 2005.

Wagner, Kim A. Thuggee: Banditry and the British in Early Nineteenth-Century India. Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.