A Defense of the 1619 Project

In the early 17th century, the port city of Luanda on the western shore of Africa, in what is today Angola, was a Portuguese colony established through the invasion and decades-long subjugation of the Kingdom of Ndongo. An estimated 50,000 Angolans, many of them captured as prisoners of war, were shipped to foreign ports as chattel slaves, often via the Middle Passage to the New World. One ship, the San Juan Bautista, carried 350 slaves bound for the Spanish colony of Veracruz, but along the way, two English privateers attacked the vessel and seized some of the Africans aboard. These two privateer ships, the White Lion and the Treasurer, landed, carrying “twenty and odd” of these enslaved Africans at the English settlement of Jamestown in Virginia in late August of 1619. Some of these men and women are recorded as having been sold to prominent settlers in Jamestown—including the colonial governor of Virginia, George Yeardley—and they are viewed as the first African slaves in the United States. Some may quibble, though. Their being the first African slaves must be specified, as some Native Americans had previously been enslaved by settlers. And some may point to African slaves in Spanish colonies in what is today Florida to argue that the slaves brought to Virginia in 1619 were not the first Africans enslaved on land that today is part of the continental United States, and this of course is true. Nevertheless, the date 1619 has long stood as the beginning of African slavery in English colonial America, and certainly as the beginning of the transatlantic slave trade in Virginia, which can be viewed as the birth of the Southern institution of slavery. Despite my caveats, recognition of 1619 as the beginning of American slavery is not controversial. Search any academic database—JSTOR, EBSCO, Gale—and you’ll see scholarly articles and books almost universally identifying 1619 as the birth of American slavery. In fact, you’ll see more disagreement about the end date, with some choosing 1862, the year of the Emancipation Proclamation, or 1865, the end of the Civil War, and some suggesting slavery did not truly end until as late as 1877, the end of Reconstruction. The point is, such milestones will always be matters of emphasis and interpretation. The only reason that the beginning date of 1619 is so quibbled over now is that 400 years later, in 2019, the New York Times Magazine published a special issue launching The 1619 Project, an initiative that sought to “reframe the country’s history” with a central focus on the lasting repercussions of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans, and it approached this simply by asking readers to consider “what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year.” Since then, the project earned its creator, journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, both a Pulitzer Prize and enough criticism that this series of articles and the educational resources it inspired are now buried beneath a stinking pile of controversy.

Whether or not you believe that our national narrative can be reasonably said to have begun in late August 1619, the beginning of this controversy undoubtedly began in late August 2019, when the Times launched The 1619 Project with the publication of numerous articles by journalists, legal scholars, and historians, as well as pieces by literary artists. Nikole Hannah-Jones’s introductory essay argues that the country’s founding principles about inalienable rights and equality were not genuine until Black Americans, to whom said equality was not extended and such rights were denied, struggled to make them real. Additional articles included sociologist Matthew Desmond’s argument that cruel labor practices representative of American capitalism had their start in the treatment of slaves on plantations, journalist Jamelle Bouie’s tracing of obstructionist partisan politics and counter-majoritarianism to the efforts of Southern politicians to preserve slavery, historian Kevin Kruse’s piece on segregation and its connection to white flight and suburban sprawl, and journalist Linda Villarosa’s discussion of some medical stereotypes and myths previously used to justify slavery that persist even today. There was significant fanfare at the time for the project’s launch, and it was viewed as an admirable undertaking by many scholars, even if they felt it wasn’t exactly breaking new ground with its claims. As Alex Lichtenstein, editor of the American Historical Review explained, it struck him “as laudable, if unexceptional.” Certainly the Times and the writers involved in the project must have expected some criticism and controversy, considering the provocative tone taken by Hannah-Jones and other contributors and the central conceit of the entire project, which suggests the popular view about our nation’s founders and their principles may be a myth and that something more distasteful lies rotting in our roots, poisoning the whole tree. However, building as they were on the sentiments of much modern historical scholarship and sociology, they likely expected opposition to arise from the Right, from conservative think tanks, whose talking points would filter out to politicians and Fox New talking heads. And certainly that opposition would come in time. But imagine their surprise when strong criticism arose first from the Left.

Leon Trotsky, modern followers of whom were the first to object to The 1619 Project on ideological grounds. Public Domain.

The first major criticism of The 1619 Project came from the International Committee of the Fourth International, on their website, the Word Socialist Web Site. If you are not familiar with the ICFI and their website, they are an organization of Trotskyists, that is, a movement that follows the Marxist philosophy of Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. In their first attack on the project, they called it “a politically motivated falsification of history.” In their view, it was an effort to further leverage “identity politics” and forge an exclusive political alliance between voters of color and the Democratic Party. This accusation really reeks of conspiracy theory, since the Democratic Party was not an official sponsor of the project and the writers who contributed to it, while liberal and progressive, are not explicitly affiliated with the party and may indeed lean farther left than many Democrats or may even have some sympathy for certain Trotskyist views and share some of their criticisms of the Democratic Party. It’s hard to tell, since journalists and historians typically try to steer clear of working directly for any political party, since it could undermine their authority and/or credibility. Regardless, though, the accusation is pretty rich, considering the central criticism that the Trotskyists leveled at The 1619 Project was itself politically motivated. They took especial umbrage with Nikole Hannah-Jones’s characterization of racism being “in the DNA” of the United States. According to the Trotskyist criticism, The 1619 Project is too pessimistic, and it fallaciously suggests that racism is an inescapable part of the fabric of American culture. In other words, the Marxists think that the Times didn’t go far enough in advocating for a change in political or economic conditions, even though such advocacy is implicit throughout the Project. To the Trotskyists, drawing attention to the ubiquity of racism is akin to throwing up one’s arms and saying there’s nothing to be done about it, and by their reckoning, the Project is problematic because it did not seek to foment an overthrow of the entire economic order. And how did they further their argument? By publishing a series of interviews with historians who also criticized The 1619 Project, though none of them on the same ideological grounds.

Among the larger group of historians interviewed on the World Socialist Web Site, only four of them, James McPherson, Victoria Bynum, Gordon Wood, and James Oakes, signed a letter penned by Princeton historian Sean Wilentz that demanded corrections be made to the articles thus far published. The letter insisted that it was only a matter of keeping the Times accountable and seeing factual inaccuracies retracted and corrected. Their complaints mostly focused on Nikole Hannah-Jones’s introductory essay, and their biggest sticking point, the inaccuracy they have spent the most time rebutting is Hannah-Jones’s assertion that “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.” These historians, and many others, refute this notion, arguing that anti-slavery activism was not prominent enough in Britain at the time for it to seem like a threat to slave holders in America, and anti-slavery principles were actually very prominent in New England, where the Revolution began, and were even proclaimed by certain revolutionaries, like Thomas Paine and John Adams. However, others have pointed out the way that the Constitution made definite concessions to slave-holders in the Three-Fifths Compromise, the Slave Insurrection Clause, and the Fugitive Slave Clause, and actually ensured the continuation of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in America for another 20 years with the Importation Clause. This can be viewed two ways: as proof that the country was already moving swiftly toward the banning of slavery and thus is not racist at its roots, or as evidence that the slaveholders here saw the world swiftly moving toward abolition and by their participation in the founding of this new country, sought to negotiate the preservation of slavery. Certainly it had that effect, and the existence of slavery was ensured in America for a half a century longer than it would exist in Britain. So the argument of Wilentz and his co-signatories that this assertion was simply not true has been vigorously challenged as well, with concessions that while Nikole Hannah-Jones may have overstated anti-slavery sentiment in Britain at the time as well as pro-slavery sentiment in colonial America, it is otherwise a matter of interpretation and could be simply corrected by removing the word “primary” from the phrase “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain.” Likewise, the letter signers took issue with Hannah-Jones’s argument that Black Americans struggled for their freedom “largely alone,” suggesting that this erases the historical contributions of white abolitionist allies, but here Hannah-Jones’s modifier exonerates, for she did not claim that they struggled entirely alone, only “largely,” and certainly this too must be conceded as a matter of perspective and interpretation, since throughout the centuries of slavery and segregation, it certainly was a lonely struggle for most who endured it. A further objection the letter signers raise is Hannah-Jones’s focus on Abraham Lincoln’s support of colonization, or the removal of freed African Americans from the country, and that while he opposed slavery he also opposed black equality. But this is not so much a matter of factual inaccuracy as it is an argument that Hannah-Jones is making, and which she supports convincingly. Indeed, it is an argument that, as Alex Lichtenstein says in his American Historical Review editorial, “many historians will find…persuasive,” and one shared by Lincoln’s esteemed contemporary, Frederick Douglass, who asserted that Lincoln “shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen against the Negro.” So in the end, while these leading scholars claimed to be correcting factual errors, they were instead disagreeing with her interpretations and, at most, quibbling over some misstatements.

16th U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, claims about whose persistent prejudices, made in The 1619 Project, some historians have argued against. Public Domain.

While Wilentz and his co-signatories are certainly well-respected historians, the fact is that Wilentz approached far more than four other historians to join his crusade against The 1619 Project, but everyone else refused to be a part of such an attack, and some have gone on record to explain that, while they may have had similar objections to specific claims made in the Project, they declined to sign Wilentz’s letter because its tone, seeming more like an attempt to discredit the entire undertaking rather than a good faith correction of facts, was unwarranted and its approach unprofessional. Nikole Hannah-Jones agrees that the letter was not a good-faith suggestion for corrections. She has herself conceded that the revision of some overstatements could improve her essay and address genuine concerns, but she points out that neither she nor the Times were approached about these concerns by the historians before or during their efforts to find other historians to sign on to the letter, which makes it seem like these critics were not interested in having a real conversation about corrections but rather were engaged in a campaign to discredit the project. And this is certainly strange, since if we take these historians at their word, they actually admire the purpose behind the project. According to Sean Wilentz, speaking to The Atlantic, “Each of us, all of us, think that the idea of the 1619 Project is fantastic. I mean, it's just urgently needed. The idea of bringing to light not only scholarship but all sorts of things that have to do with the centrality of slavery and of racism to American history is a wonderful idea.” If that is the case, and as Wilentz also said, “Far from an attempt to discredit the 1619 Project, our letter is intended to help it,” then why has it been almost universally regarded as discrediting? Probably because of its tone, identified as problematic by Thavolia Glymph, one of several black historians that Sean Wilentz failed to convince to sign his letter, among others. And why is its tone so dismissive? It has been suggested that these historians are gatekeeping, protesting the mere idea of journalists spearheading a reframing of American history. Is has been further suggested that their criticisms all boil down to the central complaint that they would have written the articles differently, the perpetual grievance of the toxic nerd. As Lichtenstein points out, Gordon Wood, in his criticism of the project, “seems affronted mostly by the failure of the 1619 Project to solicit his advice.” And according to the aforementioned Thavolia Glymph, “They think they're trying to fix the project, the way that only they know how.” Furthermore, Nell Irvin Painter, another Black historian who refused to sign the letter, has stated that “For Sean and his colleagues, true history is how they would write it.” These historian critics cannot really object that no true historians were consulted in the making of the project, though, as numerous respected historians contributed to it, including Mary Elliott, the curator of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture; Tiya Miles, a History professor at The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University; Khalil Gibran Muhammad, the Ford Foundation Professor of History, Race and Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School; and New York Times bestselling historian Kevin Kruse. And perhaps the prominence of Kruse and his Twitter celebrity can explain the intensity of principal opponent Sean Wilentz’s criticism, for Wilentz and Kruse both teach in the same department at Princeton. Could jealousy that the Times asked Kruse to contribute and not Wilentz lay at the heart of this debacle?

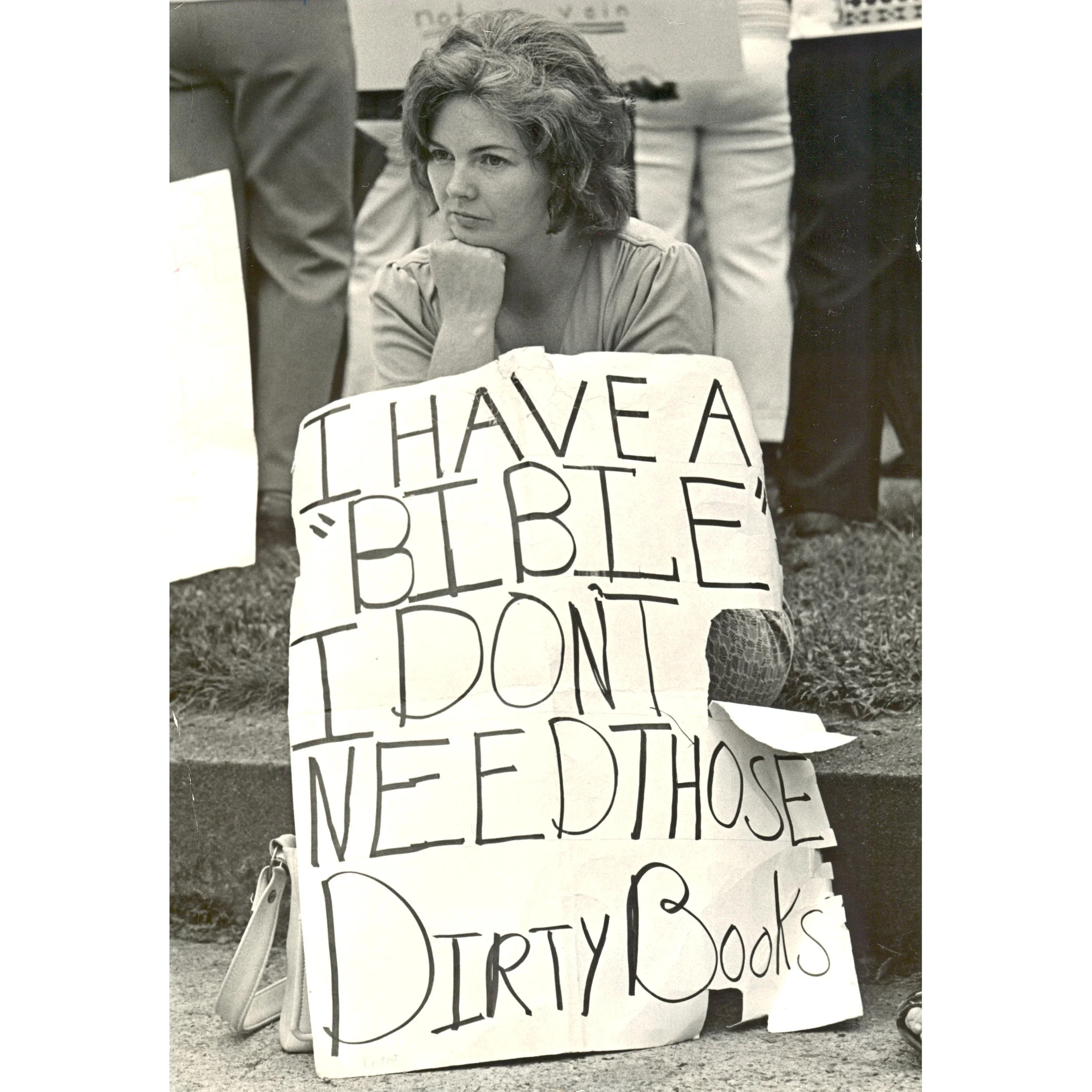

Ironically, Wilentz has expressed fear that not correcting these few errors could provide fodder to conservative critics. “One of the things I’m worried about,” Wilentz said, “is…people on the other side, politically, I suppose, who are going to use this as an event to show how corrupt the left is. Unfortunately, you’re giving them the sword to kill you with.” As true as this might have been, Wilentz’s letter did worse than handing a sword to the project’s opponents; it gave them a cannon. As would always have happened, conservative commentators and politicians criticized The 1619 Project, but with the added ammunition of well-respected historians calling the Project a distortion, they turned it into a major Republican strategy, which dovetailed with the misplaced outrage over Critical Race Theory and has further evolved into the reactionary movement to censor discussion of racial inequity in the classroom. So let’s address some of the less intellectual arguments originating from rather more expected precincts. One of the most vociferous critics actually sounds rather academic, the National Association of Scholars. If you look further into this organization, though, they are an explicitly conservative advocacy group bent on combating what it sees as a liberal bias in academia, with especial focus on opposing affirmative action and multiculturalism. Not really surprising that this group would dislike The 1619 Project, especially after Nikole Hannah-Jones was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for her work on it and the Pulitzer Center rolled out its 1619 Project Curriculum. In its eagerness to counter the project and find their own alternative anniversary to suggest was the true birth of the nation, they started the 1620 Project, memorializing the signing of the Mayflower Compact as a more appropriate true beginning of the country. What’s ironic is that, far from discrediting The 1619 Project, this impulse to find an alternative early 17th century origin of the country only legitimizes what the Times was doing, showing that it’s all simply a matter of interpretation and argument. I, for example, would argue that while it’s useful to point to the Mayflower Compact as an indication of the growing tendency toward democratic self-government, holding up the radical Puritans that we have come to call the Pilgrims and the document they drew up, permeated as it is by Christian imagery and language, does not really stand as a good representation of the birth of America for any who are not Christian. Moreover, to view the Puritans of Plymouth Colony as the true exemplars of America, rather than the settlers in Jamestown, is rather selective. Plymouth was a decidedly unusual colony among early settlements. If you view extreme piety as an American ideal, they’re you’re go-to, but their religious devotion was unusual compared to most early settlers. And of course, they did not murder women accused of witchcraft like some other Puritan settlements, but whether that makes them more representative of America and its entire history really depends on how pessimistic or optimistic your view of the country is. And more to the point of The 1619 Project, the fact that the Puritans of Plymouth colony did not keep slaves certainly stands as a counterpoint to the settlers in Virginia, but the sad fact is that, in 1614, 6 years prior to the arrival of the Puritans there, an Englishman abducted dozens of Native Americans from the area, including the man who would later serve as the Pilgrims’ own interpreter, Tisquantum, or Squanto, and sold them into slavery in Spain. So, search as we might for some sunnier and less squalid idea of our nation’s beginnings, perhaps, as The 1619 Project asserts, slavery is always there, rearing its ugly head.

The signing of the Mayflower Compact, 1620, proposed as an alternative foundational event for American history by critics of the 1619 Project. Public domain.

Predictably, amid the continuing George Floyd protests, the 45th President decided not to seek any redress for the demonstrators’ very real grievances, and instead promoted further division, latching onto The 1619 Project as an issue to run on in his reelection campaign. On September 17th, he convened the first so-called White House History Conference at the National Archives, and he laid the responsibility for recent unrest not on police violence or systemic injustice but rather on progressive indoctrination in schools, explicitly blaming the 1619 Project, which by that time, a year after its publication, had seen some use in classrooms. His solution was to establish by executive order a 1776 Commission to promote “patriotic education.” The irony abounds with this commission. Trump and the GOP attack the 1619 Project for being a distortion of history and liberal propaganda, yet to correct the historical record, he established a commission whose membership is completely devoid of actual historians and instead is filled rank and file with conservative activists and politicians and even some of Trump’s own policy advisers. Of course, Trump then went on to lose the election and rushed the release of the report only a month after assembling the commission, on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, making one of his final acts in office the release of a report on history scholarship that lacks any scholarly source documentation and doesn’t even properly credit any of its own authors. Without any apparent struggle with the cognitive dissonance, this report decries progressive propaganda while simultaneously propagandizing by likening progressivism to fascism and listing it alongside slavery as one of the “challenges to America’s principles.” It warns of the dangers of progressive indoctrination in schools while recommending a kind of government-sponsored indoctrination program to ensure traditional hero worship of the country’s founders, seeking to regress history education back to the myth-making curriculum of the 19th century. While Sean Wilentz could only find 4 other respectable historians to put their names on his letter censuring The 1619 Project, the American Historical Association’s condemnation of the 1776 Commission’s report has been endorsed by 47 highly credible historical and scholarly organizations. On his first day in office, just a couple days after the report’s release, President Biden saw fit to disband the commission and take down its report’s official webpage.

As with Critical Race Theory, the central objection to The 1619 Project has been that it is being taught to our youth. Unlike CRT, though, which isn’t really being taught outside of academia, The 1619 Project actually has inspired a high school curriculum presented by the Pulitzer Center. However, as the editor-in-chief of the New York Times Magazine, Jake Silverstein, has observed, “[T]here is a misunderstanding that this curriculum is meant to replace all of U.S. history.” In fact, Silverstein points out, “It's being used as supplementary material for teaching American history." And as Alex Lichtenstein, the previously cited editor of the American Historical Review, has noted, “[N]o specific, detailed analysis of the proposed K-12 curriculum accompanying the 1619 Project has yet been offered by teachers or scholars of history-teaching,” calling this blind spot “puzzling and ultimately inadequate to the vigor of the objections.” What seems to be a universal assessment among scholars and teachers of American history is that The 1619 Project’s purpose is worthy because history education about slavery and its lasting effects is sorely lacking. The Southern Poverty Law Center found in its 2018 report “Teaching Hard History” that “[s]chools are not adequately teaching the history of American slavery, educators are not sufficiently prepared to teach it, textbooks do not have enough material about it, and – as a result – students lack a basic knowledge of the important role it played in shaping the United States and the impact it continues to have on race relations in America.” More specifically, they discovered that “few American high-school students know that slavery was the cause of the Civil War, that the Constitution protected slavery without explicitly mentioning it, or that ending slavery required a constitutional amendment.” Hofstra University’s director of social studies education Alan Singer, a historian of slavery in New York, has detailed how, in New York State, high school social studies curriculum “minimizes the role of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the sale of people, and the sale of slave-produced commodities in global and United States history.” Meanwhile, among the teachers who are actually choosing to use the Project in their classes, it is clear that the project’s chief merit is that it has started a sorely needed discussion, despite or even because of all the controversy surrounding it. As explained by John Duffy, faculty fellow of the University of Notre Dame’s Klau Center for Civil and Human Rights, when he teaches The 1619 Project in his English classes, he uses the controversy to encourage critical thinking: “While I encourage students to draw their own conclusions about the controversies, we do not attempt to decide collectively which perspectives are more accurate. Instead, we discuss reasons historians disagree, how such disagreements are argued and what this suggests about historical truths. We consider who gets to tell the story of a people and what is at stake in the telling.” And this is how the project should be used, and how I imagine any teacher worth anything would use it. So what does this tell us about Republican laws to cripple the discussion of race in the classroom, some of which mention The 1619 Project by name? Either that the legislators lack a fundamental understanding of modern pedagogy, or that they are simply afraid such frank and critical discussions will lead to students developing viewpoints opposed to theirs.

Further Reading

“The 1619 Project.” The New York Times Magazine, August 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html.

“The 1619 Project Curriculum.” Pulitzer Center, pulitzercenter.org/lesson-plan-grouping/1619-project-curriculum.

“AHA Condemns Report of Advisory 1776 Commission (January 2021).” American Historical Association, 20 January 2021, www.historians.org/news-and-advocacy/aha-advocacy/aha-statement-condemning-report-of-advisory-1776-commission-(january-2021).

Anderson, James. “U. professors send letter requesting corrections to 1619 Project.” The Princetonian, 6 Feb. 2020, www.dailyprincetonian.com/article/2020/02/u-professors-send-letter-requesting-corrections-to-1619-project.

Autry, Robin. “Trump's '1776 Commission' tried to rewrite U.S. history. Biden had other ideas.” NBC News, NBC Universal, 21 Jan. 2021, www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/trump-s-1776-commission-tried-rewrite-u-s-history-biden-ncna1255086.

Crowley, Michael, and Jennifer Schuessler. “Trump’s 1776 Commission Critiques Liberalism in Report Derided by Historians.” The New York Times, 18 Jan. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/01/18/us/politics/trump-1776-commission-report.html.

Kazin, Michael. “The 1776 Follies.” The New York Times, 1 Feb. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/02/01/opinion/trump-1776-commission-report.html.

Lichtenstein, Alex C. “From the Editor’s Desk: 1619 and All That.” American Historical Review, vol. 125, no. 1, Feb. 2020, pp. xv–xxi. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1093/ahr/rhaa041.

Serwer, Adam. “The Fight Over the 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts.” The Atlantic, 23 Dec. 2019, www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/12/historians-clash-1619-project/604093/.

Shuster, Kate. “Teaching Hard History.” Southern Poverty Law Center, 31 Jan. 2018, www.splcenter.org/20180131/teaching-hard-history.

Silverstein, Jake. “We Respond to the Historians Who Critiqued The 1619 Project.” The New York Times, 20 Dec. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/12/20/magazine/we-respond-to-the-historians-who-critiqued-the-1619-project.html.

Singer, Alan J. “Defending the 1619 Project in the Context of History Education Today.” History News Network, The George Washington University, 20 Dec. 2020, historynewsnetwork.org/article/178586.

Strauss, Valerie. “Professor: Why I teach the much-debated 1619 Project — despite its flaws.” The Washington Post, 14 June 2021, www.washingtonpost.com/education/2021/06/14/professor-why-i-teach-controversial-1619-project/.

Waxman, Olivia B. “The First Africans in Virginia Landed in 1619. It Was a Turning Point for Slavery in American History—But Not the Beginning.” TIME, 20 Aug. 2019, time.com/5653369/august-1619-jamestown-history/.

Wulf, Karin. “Why the Myths of Plymouth Dominate the American Imagination.” Smithsonian Magazine, 24 Nov. 2020, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/why-myths-plymouth-dominate-american-imagination-180976396/.