Curriculum Controversies in America

Over the last year, a conservative talking point has emerged that a new and dangerous kind of “woke racism,” originating from an arcane and supposedly nefarious ideological academic discipline called Critical Race Theory, is being taught to children in schools, amounting to a kind of un-American indoctrination. If you’ve paid attention, this view has garnered a lot of traction and become a favorite grievance on the right, resulting in many local school board meetings devolving into a venue for the breathless protests of ill-informed parents. The result has been recent legislation in states like Oklahoma, Tennessee, Iowa, and Idaho, with Republican-controlled legislatures, banning the discussion of Critical Race Theory, or CRT for short, in schools, a dreadful development indeed for free speech and academic freedom. As many have pointed out, though, CRT is not actually taught in public elementary or secondary schools. It’s an approach to legal scholarship that emerged in academia in the ‘70s and ‘80s, in which the inherent discrimination of public policies is analyzed with a view toward improving equity under the law. This scholarly subject has become the chief bogeyman to conservatives, who conflate it with all efforts to address systemic racism and cultivate anti-racist views and approaches in various fields, in both the public and private sector. In the wake of the George Floyd protests last year, many organizations began, admirably, to acknowledge the fact that the long history of racism in America may be present in their own administrations and bureaucracies, and to hold seminars and meetings to educate themselves about systemic racism and how they might be able to effect change within their domains. Of course, some fragile attendees at these meetings, when asked to examine the possibility that they may have benefited from privileges others are denied, balked and became defensive and suggested that such frank discussions of racism amounted to another kind of racism, one targeting them. Some even recorded their Zoom sessions, thinking of themselves as heroic whistleblowers on this new woke culture invading their safe spaces, and sent the footage to journalists to blow the whole thing wide open. Of course, one conservative journalist obliged. His name is Christopher Rufo, and he wrote a series of articles supposedly “exposing” these anti-bias seminars in Seattle, even though they were not closely held secrets or anything that the organizations who held them were embarrassed about. But Rufo believed he was uncovering a vast conspiracy. In the materials leaked to him, he unsurprisingly found references to some well-known books on anti-racism by authors like Ibram Kendi and others, and then, examining those books, he found further references to the legal scholarship of Kimberlé Crenshaw, who originated Critical Race Theory. Rufo shows his lack of experience in performing academic research in that, rather than understanding the nature of academic scholarship as a conversation between texts and authors over decades and centuries, in which supportive materials are cited to strengthen arguments, just as they would be by those who assert an opposing view, Rufo saw this as some kind of insidious conspiracy, fancying himself a kind of Robert Langdon, uncovering evil power structures through his rather cursory readings of a few works, all of whose points he seems to have missed entirely.

Christopher Rufo on Fox New, starting the CRT controversy. Image may be subject to Copyright.

Rufo believes that the perennial specter of Marxism lies at the root of Critical Race Theory and all anti-racist activism, mostly because of some anti-capitalist comments made by certain of the authors frequently cited, who recognize that discriminatory public policies are deeply enmeshed in our economic system, but he entirely disregards the more obvious cultural basis of these works in the Civil Rights Era struggles of Martin Luther King Jr. and others. He proposes that this activism started in academia and is now deeply embedded in our bureaucracies—again, taking a conspiratorial view, as if these anti-bias seminars were somehow foisted on unwilling organizations rather than sought out by administrators who may actually agree there are deeply entrenched problems in our society that they don’t want to be a part of. In Rufo’s view, anti-racist activism, and by extension CRT, which he paints as the evil puppet master, is simply about overturning the system by humiliating and shaming White people. If he had actually managed to grasp the message of Ibram Kendi’s work, though, he would understand that’s not what anti-racism is about. Perhaps it would have been better if Rufo had read Kendi’s simplification of anti-racism in the form of his children’s book, Anti-Racist Baby, which spells out for still developing minds the fact that anti-racism is not “reverse racism,” a term which itself is wildly racist, in that it suggests racial discrimination and bias is meant to be directed at only non-White people. Instead, as Kendi’s children’s book states, anti-racism celebrates our differences and identifies policies rather than people as the problem. But it’s Kendi’s suggestion that we use our words to actually talk about racism that seems to be the problem for Rufo and others. The backlash against Critical Race Theory, which is actually a backlash against anti-racism activism generally, is at its heart a resistance to talking about racism at all. Think about it in terms of gun violence. In the aftermath of a mass shooting, there are calls to address the issue and talk about gun control, and there is always a resistance, suggesting, “Now is not the time,” when clearly there is no better time. After the George Floyd protests, now clearly is the time to talk about systemic racism, and the protests against teaching Critical Race Theory are a clear attempt to squelch such conversations. Rufo recognized that Critical Race Theory was the perfect term to spark conservative outrage. The word “critical” being inflammatory to defenders of the status quo, the word “race” being outrageous to those who refuse to recognize that they may have been born privileged because of the color of their skin, and the word “theory” suggesting that it is not fact and can therefore be vigorously refuted. Rufo and his views were welcomed onto Fox News Channel by Tucker Carlson, and his calls for the President to issue an executive order were answered by Trump, who signed an order coauthored by Rufo limiting speech about race in seminars delivered to federal employees. But this was just the beginning. Even though Critical Race Theory is not taught in public schools, Rufo’s activism has sparked a huge push from the right to ban it, and these laws, in effect, seem to outlaw the candid discussion of race in classrooms generally. The vague contours of some of these laws seem to suggest that classic literature that explicitly addresses racism, like Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man or Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird could be banned from English classrooms. Especially hard hit would be American history classes, for how can students and teachers honestly discuss colonialism, slavery, the decimation of Native American tribes, Jim Crow, the Civil Rights Era, or really any aspect of American history without acknowledging and openly discussing racism? This legislation is little more than a ban on ideas, and it is not the first time that the classroom has become a theater in which to wage the culture war.

To suggest that the current furor over discussing systemic racism with students in the classroom originated with Rufo’s conspiracist view of Critical Race Theory would be to turn a blind eye to the fact that he is capitalizing on long-standing sentiments among conservatives that liberals control academia (when in fact, perhaps, progressive ideas just stand up better to scholarly scrutiny), that the history of America is being distorted and falsified by the Left (when in fact historical revision to achieve better accuracy and understanding is a central tenet of historical research, without which we may today still believe falsehoods like that the women executed in 17th-century Salem really were Satan-worshipping sorceresses), and that changes to elementary and high school curricula represent indoctrination (when it actually represents efforts to improve education and prepare students for the academic rigor of college, which will in turn help them succeed in life and become better citizens generally). It is pretty hard to indoctrinate through the teaching of critical thinking, which is what lies at the core of historical revision and recent changes in curricula, and which serves as the foundation of all efforts to recognize the systemic racism that has been ignored or denied for so long. As I try to emphasize in this podcast, critical thinking encourages every individual to analyze and evaluate received information, to sift through it for falsehoods and errors in logic and reason, and to try to achieve a more perfect understanding of the truth, as far as it can be discerned. This is something that even conspiracy theorists and denialists claim to value. For example, take Glenn Beck, currently a vocal opponent of what he calls Critical Race Theory in schools (which again, seems to just be just be any acknowledgement of racism’s existence and the systemic preservation of privileges for some and not others). He likes to encourage critical thinking too! However, when he disagrees with where critical thinking leads students, he calls it indoctrination. In fact, back in 2012, ridiculously enough, the Republican Party of Texas actually made opposition to critical thinking a plank in their platform! When this resulted in controversy, they tried to claim that they actually only opposed a specific teaching approach called Outcome-Based Education which they argued was simply relabeled as higher order thinking and critical thinking. Here again, they rely on the argument that a relabeling has occurred, just as they say anti-bias training and anti-racism activism is actually repackaged Critical Race Theory, which is really Marxism, they’ll say. But the Texas GOP platform was clear about what they found offensive in critical and higher order thinking skills: that they “have the purpose of challenging the student’s fixed beliefs.” So already we see the aversion to having students exposed to what they view as ideas that may challenge the status quo.

Lynn Cheney on Charlie Rose amid the History Standards controversy. Image may be subject to copyright.

The political battle over how history is taught itself has a long history. Before the uproar over anti-racist approaches to education and so-called Critical Race Theory, there was outrage over the New York Times’ 1619 Project, which sought to place slavery and its effects at the center of our understanding of America’s founding and subsequent history. In response to this series of publications, the Trump administration even founded a commission to defend a more traditionalist view of American history, to denounce progressivism in education as indoctrination, and to promote “patriotic education,” despite the fact that it is not the federal government’s place to control instructional programs or curriculum. However, the controversy over the 1619 Project deserves an entire episode, or at least a minisode, in its own right, so suffice it to say here that Christopher Rufo was latching onto this controversy when he conjured the specter of CRT. This more recent controversy over approaches to the teaching of American history echoes the controversy over National History Standards in the mid-1990s. In the fall of 1994, former Vice President Dick Cheney’s wife Lynne Cheney, who served as the chair for the National Endowment of the Humanities, sparked a lengthy political controversy by writing a rebuke of the forthcoming national standards which her organization had funded, developed by the National Center for History in Schools at UCLA, which again her organization had chosen for the task. Her central complaints, which were thereafter parroted by conservative talk radio hosts, talking heads, and politicians, were that the new standards focused too much on injustices related to race and gender and not enough on the traditional hero worship of former textbooks. It was all so negative, she whined, and she even resorted to score-keeping, counting the number of times that McCarthyism and the Ku Klux Klan were mentioned and bemoaning that Alexander Graham Bell and the Wright Brothers didn’t receive equal page space. While critics derided the proposed standards as an example of political correctness run amok, historians defended them as rigorous and dismissed the backlash as a reactionary attack on modern historical scholarship, which had for some time sought to bring the marginalized and underrepresented further into focus and do away with insupportable myths about our country. In the end, though, since these were just voluntary standards, and since most of the complaints stemmed from the numerous teaching examples provided, which were confused for curriculum, and not from the actual standards themselves, whose criteria were universally praised, a few simple revisions sufficed to appease the detractors and dampen the fires of controversy.

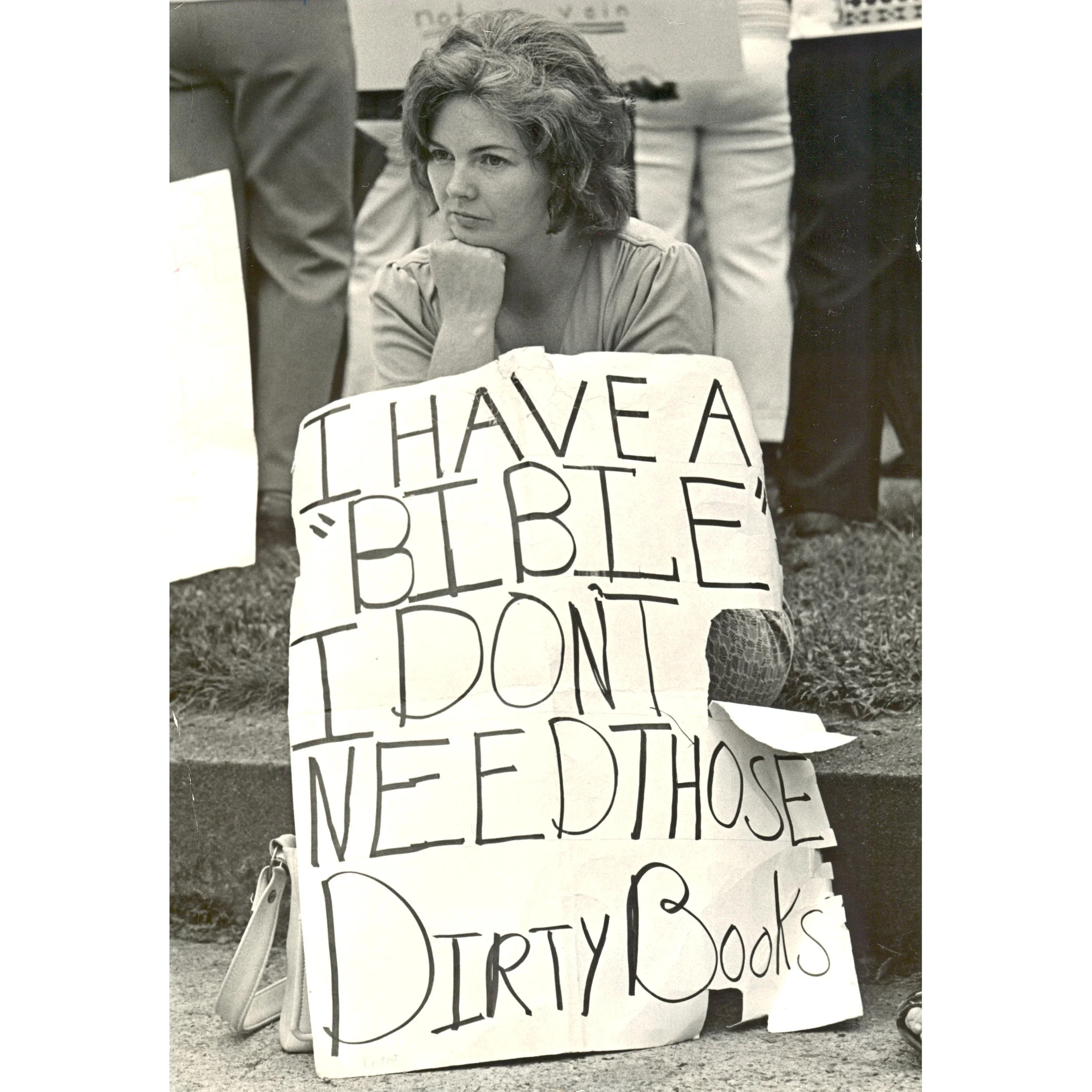

Woman protesting textbooks in Kanawha County, West Virginia. Via West Virginia Public Broadcasting

Curriculum controversies have not been exclusive to History, either. One of the most egregious examples of political scrimmage over teaching materials centered on literature reading lists. The story of the Kanawha County Textbook War sounds extremely similar to the protests seen this year in school board meetings. In April 1974, the Board of Education assembled in this West Virginia county to discuss how they would meet a mandate to include in their curriculum “multiethnic and multiracial literature.” One board member, Alice Moore, who had campaigned for her seat by protesting sex education, a curriculum controversy that has been consistent and ubiquitous in its own right. She seems to have seen in the new lit curriculum another opportunity for outrage. She found the poetry of e. e. cummings pornographic, the writings of Sigmund Freud atheistic, the Autobiography of Malcom X un-American, and generally complained that works by Black authors like James Baldwin were too depressing in their description of life in ghettoes. “[T]extbooks should show life as it should be,” she argued, “not life as it is.” Her rhetoric enflamed the resentments of parents, who boycotted county schools. Thousands marched in protest against these “dirty books.” They circulated pamphlets that claimed the new reading material contained sexually explicit passages, but these assertions proved to be false. In fact, unsurprisingly, neither Alice Moore nor any of her followers had read the literature they were railing against, which they openly admitted, claiming that they didn’t need to subject themselves to such radical propaganda to know it was harmful. The protests quickly turned violent. Property was destroyed as protesters shot firearms at empty school buses and firebombed an empty school building. They even set off dynamite at the district offices. Beatings and shootings occurred, board meeting broke out into riots, and people were arrested, and not only the violent protestors; Alice Moore managed to get other school board members arrested for contributing to the delinquency of a minor. Even though the violence eventually subsided and the books being protested were added to the curriculum, this conservative terrorism accomplished somewhat the outcome desired: it had a definite chilling effect on academic freedom and freedom of speech in the classroom, as for some time afterward, teachers censored themselves for fear of stoking controversy, avoiding potentially divisive books like 1984 and even skipping over biology lessons about animal reproduction for fear that it came too close to sex education. At the time, Alice Moore presented herself as just a concerned parent, but since, historians have suggested that she was more of a right-wing provocateur with connections to other organizations that had been protesting progressive curriculum since the 1960s, including the Christian Crusade, which focused on removing sex education from schools, and even that far-right anti-communist group who saw socialist conspiracies everywhere, including in curriculum that they believed was little more than Marxist indoctrination, our old friends, the John Birch Society.

Protest to progressive curriculum as Communist indoctrination was, unsurprisingly, common during the Second Red Scare, in the era of McCarthyism. Indeed, the House Unamerican Activities Committee, well known for its investigation of Hollywood, which resulted in so many careers ruined because of blacklisting, also went after teachers that they suspected of indoctrinating youth. In 1959, the HUAC planned to hold one of its dreaded hearings in San Francisco, California, where it subpoenaed dozens of teachers. In response, local college professors organized San Franciscans for Academic Freedom and Education, or SAFE, and solicited a broad base of bi-partisan support even among moderate and conservative organizations on the grounds that the federal government has no place in controlling local education. This public resistance led to the HUAC canceling its hearings for the first time, but they came back the next year with a new spate of subpoenas. They were met by thousands of demonstrators, representing a wide range of San Francisco society, including students, politicians, and other activists, in a significant protest movement that prefigured the anti-war protest movement of the 1960s. The response of authorities on the second day of the protest was much the same as would be encountered in later years as well, with truncheons and fire hoses wielded against the protestors. But on the third day, some 5,000 protestors marched in downtown San Francisco, and this display helped to encourage nationwide opposition to the HUAC, whose spell of fear over the country was finally breaking.

Anti-HUAC protesters at San Francisco City Hall, with seated Anti-HUAC protesters, after being doused with fire hoses. Via Zinn Education Group.

The absurdly paranoid John Birch Society and the witch-hunting HUAC were not the only groups to fear the creeping influence of Marxist thought into classrooms. One organization was the veterans association, the American Legion, which had for decades made it their mission to criticize and reject any textbooks they found to be “un-American.” One major target of the American Legion was the work of Harold Rugg, whose social studies textbook series, Man and His Changing Society, sought to highlight both the strengths and the weaknesses of America in order to demonstrate to younger generations where social change may be beneficial. The books sold widely and were adopted in many school districts, becoming a standard for years. However, the encouragement of change was viewed suspiciously, and the depiction of America as anything less than perfect was seen as unpatriotic. In the mid-1930s, some parents complained that they were communistic, and during World War II, the controversy expanded to the point that the books were being derided as treasonous propaganda. In fact, the books simply encouraged students to think critically about social problems and come to their own conclusions. Familiarly, protestors gleefully condemned the books without having bothered to read them, saying that they didn’t need to read them because they had heard all they needed to hear about the author. After enough sustained controversy, school administrators banned the texts in many districts despite their admiration for them simply because they did not want to deal with the anti-Communist crusaders, and not content to see Rugg’s books simply removed from the schools, the protestors, Nazi-like, held numerous public book burnings. This controversy did more than just remove and destroy Rugg’s books; it set back progressive education decades, as for years afterward, other textbook authors shied away from addressing social issues and avoided any implication that America could improve in any way.

This inclination among many on the right to desire a white-washing of America and our history finds its apotheosis in the efforts of the United Daughters of the Confederacy to recast the history of the South and promulgate the Lost Cause Myth that I spoke about in my episode Jubal Early’s Lost Cause. The United Daughters of the Confederacy are perhaps best known today for their efforts to erect monuments to white supremacists, monuments regularly targeted by racial justice advocates who continue working to get them removed. To those who might protest that Confederate monuments aren’t monuments to white supremacists, first I would point out that in 1926, the United Daughters of the Confederacy actually erected a monument to the Ku Klux Klan in Concord, North Carolina. But that blatant evidence aside, any who might protest that a monument to the Confederacy or its leaders does not itself represent a monument to white supremacy has accepted the false notion of the Lost Cause Myth that the South was fighting for anything other than a social order based entirely on the patrician rule of elite white families over the poor and their exploitation of Black chattel slaves as forced labor. I have refuted the Myth of the Lost Cause before and won’t retread the same ground here, but suffice it to say that the success of the Lost Cause Myth, the reason it is still so commonly repeated today, can be attributed to the efforts of the United Daughters of the Confederacy to remove textbooks they felt portrayed the Southern Cause in a negative light and install curriculum that exalted the South and distorted the truth about the war and about slavery.

A North Carolina chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, via Encyclopedia Virginia.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy, or the UDC, took up their crusade to indoctrinate Southern youth with the Myth of the Lost Cause from other organizations, namely the United Confederate Veterans and the Sons of Confederate Veterans, who in the 1890s balked at the portrayal of Southern planters and the Confederacy in histories written by Northern writers, which understandably condemned their treatment of slaves and their entire economic and social system, and further blamed them for the war. Motivated by their desire to maintain the dominance of patrician families in the postbellum South, they undertook a campaign to systematically vindicate themselves through propaganda and indoctrination. They removed Northern textbooks from their schools, accusing even the Encyclopedia Britannica of malicious distortion, and then wrote, published, and installed their own history texts onto school bookshelves. Their books, and others afterward promoted by the UDC, maintained the idea that the Confederacy did not secede in order to preserve the slavery on which their economy and social hierarchy was built but rather because of dignified and honorable ideals about state sovereignty, and more than this, they perpetuated the even older lies that slave owners were “kind and lenient” to their slaves and that “[t]hey in turn loved their master.” They even went so far as to suggest that, without the guidance of an overseer, slaves would have turned to cannibalism, which they claimed was their natural tendency in Africa. Meanwhile, they glorified white Southerners, describing the idyllic mansions of the plantation system and calling it “a civilization that gave us brave and true men and pure and noble women.”

The taking up of the cause to indoctrinate Southern youth with these ideas was the natural evolution of the UDC’s efforts to memorialize the Confederacy. Rather than just inanimate statues, they sought to create “living monuments,” as historian Karen Cox puts it. And their campaign was extremely effective. Beyond expunging history textbooks they disliked and getting Confederate-friendly texts adopted, they went after teachers and administrators who resisted and drove them out of schools. They sponsored essay contests that required students to use their texts, they filled the schools with teachers from among their own ranks, and they composed lesson plans for the rest. They put up portraits of Confederate figures in the schools, hung Confederate battle flags in classrooms, and even petitioned to have schools named after Confederate “heroes.” Perhaps most disturbingly, like the formation of the Nazi youth, the UDC organized Children of the Confederacy auxiliaries, grooming the kids for later membership in the UDC and the Sons of Confederate Veterans, having the children themselves cut the cord to unveil each new monument. This is what we must fear when conservative voices protest progressive curriculum. They will cry “Indoctrination!” but true to their nature, it is just projection, for what they really object to is any challenge to the status quo. They recognize that a progressive curriculum prevents them from propagandizing in schools and brainwashing young minds.

Those who protest anti-racist approaches to education, or what they have been told is Critical Race Theory, inevitably resort to the criticism that progressive curriculum is itself biased, or even racist. However, the lessons they protest often involve just the simple acknowledgement of racism’s continued existence or any encouragement for students to openly discuss and analyze disparities in representation and the systems of privilege at work in the world. Any calls for fairness or teaching both sides may seem reasonable, but you must consider what they’re saying. Even the United Daughters of the Confederacy claimed to want “impartial” history, but how is it edifying or moral to give equal time and emphasis to a point of view that exonerates and exalts white supremacy? The entire notion of “teaching the controversy” is always only a demand that inarguable or harmful ideas be unduly recognized or accorded merit they do not possess. Take the idea of “creation science.” It was not taught in science classrooms because it is not science. There is not controversy about it among actual scientists. Christian fundamentalists only attempted to portray evolution as controversial in order to put religion in science classrooms. Likewise, today, opponents of CRT argue that equal time must be awarded to any opposing view when it comes to racism in society and history. This has led to suggestions that any lesson on the Holocaust, for example, may need to be balanced with equal time given to Holocaust denial. The simple fact is that not all controversies have two equal sides, and hate should not be presented to children as an acceptable view to take. And the entire notion that teaching about racism is biased doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Trends in progressive curriculum, which as I’ve shown are not new, actually are an effort to redress cultural bias and one-sidedness in education, acquainting students with the experiences of underrepresented and marginalized groups that have previously been excluded from textbooks. To claim this inclusion is biased or exclusionary is exactly the same as refusing to explicitly acknowledge that Black lives matter and instead insisting only on repeating that all lives do. It reveals a fundamental, racist aversion to recognizing the struggles of any group other than one’s own.

Further Reading

Appleby, Joyce. “Controversy over the National History Standards.” OAH Magazine of History, vol. 9, no. 3, [Oxford University Press, Organization of American Historians], 1995, pp. 4–4, www.jstor.org/stable/25163026.

Bailey, Fred Arthur. “The Textbooks of the ‘Lost Cause’: Censorship and the Creation of Southern State Histories.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 75, no. 3, Georgia Historical Society, 1991, pp. 507–33, www.jstor.org/stable/40582363.

Camera, Lauren. “Federal Lawsuit Poses First Challenge to Ban on Teaching Critical Race Theory.” U.S. News and World Report, 20 Oct. 2021, www.usnews.com/news/education-news/articles/2021-10-20/federal-lawsuit-poses-first-challenge-to-ban-on-teaching-critical-race-theory.

Carbone, Peter F. “The Other Side of Harold Rugg.” History of Education Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 3, [History of Education Society, Wiley], 1971, pp. 265–78, doi.org/10.2307/367293.

Cox, Karen L. “The Confederacy’s ‘Living Monuments.’” The New York Times, 6 Oct. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/10/06/opinion/the-confederacys-living-monuments.html.

Gershon, Livia. “How One Group of Teachers Defended Academic Freedom.” JSTOR Daily, 29 Dec. 2019, daily.jstor.org/how-one-group-of-teachers-defended-academic-freedom/.

Huffman, Greg. “The group behind Confederate monuments also built a memorial to the Klan.” Facing South, 8 June 2018. www.facingsouth.org/2018/06/group-behind-confederate-monuments-also-built-memorial-klan.

---. “TWISTED SOURCES: How Confederate propaganda ended up in the South's schoolbooks.” Facing South, 10 April 2019, www.facingsouth.org/2019/04/twisted-sources-how-confederate-propaganda-ended-souths-schoolbooks.

Paddison, Joshua. “Summers of Worry, Summers of Defiance: San Franciscans for Academic Freedom and Education and the Bay Area Opposition to HUAC, 1959-1960.” California History, vol. 78, no. 3, [University of California Press, California Historical Society], 1999, pp. 188–201, doi.org/10.2307/25462565.

Ravitch, Diane. “The Controversy over National History Standards.” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 51, no. 3, American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 1998, pp. 14–28, doi.org/10.2307/3824089.

Skinner, David. “A Battle over Books.” HUMANITIES, vol. 31, no. 5, Sep./Oct. 2010, www.neh.gov/humanities/2010/septemberoctober/statement/battle-over-books.

Stanley, William B. “Harold Rugg and Social Education: Another Look.” Journal of Thought, vol. 18, no. 4, Caddo Gap Press, 1983, pp. 68–72, www.jstor.org/stable/42589033.

Kay, Trey. “The Great Textbook War.” West Virginia Public Broadcasting, 17 Oct. 2013, www.wvpublic.org/radio/2013-10-17/the-great-textbook-war.

Wallace-Wells, Benjamin. “How a Conservative Activist Invented the Conflict Over Critical Race Theory.” The New Yorker, 18 June 2021, www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-inquiry/how-a-conservative-activist-invented-the-conflict-over-critical-race-theory.

Waxman, Olivia B. “Trump's Threat to Pull Funding from Schools Over How They Teach Slavery Is Part of a Long History of Politicizing American History Class.” Time, 16 Sep. 2020, time.com/5889051/history-curriculum-politics/?amp=true.

Winters, Elmer A., and Harold Rugg. “Man and His Changing Society: The Textbooks of Harold Rugg.” History of Education Quarterly, vol. 7, no. 4, [History of Education Society, Wiley], 1967, pp. 493–514, https://doi.org/10.2307/367465.