A Very Historically Blind Christmas

I love Christmas: the family time, the music, the classic movies, the decorations, the aroma of evergreen trees and spice apple, the taste of gingerbread with my coffee and nutmeg in my eggnog. I am not, however, much of a churchgoer or man of faith; therefore, I have some ambivalence about this holiday which is so often and heatedly defended as a Christian tradition. We must remember the reason of the season, and we must keep Christ in Christmas, or so many remind us while lamenting a culture that does not encourage people to keep the nativity scene at the forefront of all thoughts throughout December. Recently, I saw an image being posted on social media with these statements: “Christmas is based on a pagan holiday. Jesus wasn’t born in December. Christmas trees are a Heathen tradition.” And of course, this wasn’t the first time I’d heard these claims. Being something of a know-it-all and a pedant who is only too happy to challenge preconceived notions about both history and religion, I have been known to make such statements myself. But of course, as I have learned in making this show, critical thought challenges all preconceived notions, not only the ones that you dislike and want to dispel. The claims of the agnostic, the atheist, and the anti-religious must be examined just as skeptically and fairly as any assertions made by the religious. So this holiday season, I’ve set out to explore the veracity of these claims and get to the bottom of just how pagan or Christian are Christmas’s origins and traditions.

Perhaps the first assertion we should examine is that Jesus Christ was not born on December 25th, as this is a frequent point used to undermine the entire Christian basis of the holiday. In truth, we don’t know when Jesus was born. The two gospels that depict the nativity, Matthew and Luke, fail to record a birthdate or even to identify the month or the season of his birth. We can, however, make some judgments based on details that are included. Both gospels indicate vaguely that the story of the Nativity took place during the reign of Herod the Great, King of Judea, but there are inconsistencies. Matthew says the Christ child was born during his reign, and goes on to tell the story of Herod’s Massacre of the Innocents, but Luke actually only mentions the reign of Herod as being the time when an angel foretold of the birth of John the Baptist and implies a significant passage of time between that and Mary’s angelic visitation. Rather, Luke explicitly places Christ’s birth during the Census of Quirinius, taken during the imposition of Roman rule, for which male landowners were required to return to their ancestral homes and be counted. Thus a problem arises with the timeline, as this census took place a decade after Herod’s death, which would make the two nativity narratives entirely contradictory. Moreover, it would not make sense for Joseph to take Mary on his journey while she was “great with child” if she need not be counted for the census when she could instead remain in the comfort of their home on whatever land Joseph presumably owned. And one detail stands out from Luke as evidence that whatever the month of Christ’s birth, it couldn’t be December, this being the verse that states there were shepherds watching over their flocks in the fields at night when Mary delivered the child. This would seem to place his birth during a warmer time of year. However, if these inconsistencies tell us anything, it is that we should not be looking to Matthew and Luke as accurate records of the past. The most likely explanation for all of these discrepancies is that, writing about events at a seventy to eighty year remove, the authors simply got things wrong or invented details to flesh out their stories. So why, a few hundred years later, did the church settle on December 25th as the Feast of the Nativity? Some have claimed that it was a simple matter of doing the math, that December 25th falls nine months after March 25th, when the Feast of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary is observed, celebrating Christ’s immaculate conception. One might then reasonably ask how they determined March 25th to be the anniversary of the annunciation, and the answer raises the odd notion that martyrs are predestined to be martyred on the anniversary of their conceptions. But there may be a simpler explanation. Records of the first Feast of the Nativity predate the first Feast of the Annunciation by about 100 years, so if simple math determined these dates, then if anything, that math was done in reverse, counting backward nine months from December 25th to be certain the date of the Annunciation lined up with the chosen date of the Nativity. So the question remains, why choose December 25th?

Our answer may indeed lie in pagan and secular traditions in the form of midwinter feasts and festivals that were common and popular in the Roman Empire during the time when Christianity was only just establishing its own traditions. The first record we have showing December 25th as the date of Christ’s birth comes from a calendar produced in Rome in 354 CE, an era when Christianity was vying for ascendancy against various pagan traditions. There is a quotation from a supposed 4th-century scribe called Scriptus Syrus that appeared as an annotation on another work, and it clearly makes the claim that the Christian Church simply adopted pagan traditions for its own purposes: “It was a custom of the pagans to celebrate on the same Dec. 25 the birthday of the sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity …Accordingly, when the church authorities perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnized on that day.” This is the heart of the contention, that the Christmas we know is simply a pagan celebration appropriated by Christianity out of either convenience or for the purpose of asserting religious dominance, which of course it succeeded in doing. The quote itself is suspect, though. The annotation actually appeared on an 18th-century edition of a 12th century work, and the name Scriptus Syrus only means “a Syrian writer.” Therefore, it doesn’t appear to be a claim made in the 4th century, but rather one made some 800 years later by an unknown writer. Still we may ask whether or not it is true. What was this festival of the birthday of the sun? This can easily be recognized as dies natalis solis invicti, or the birthday of the unconquered sun, a civil holiday timed to coincide with the winter solstice to honor the symbolic rebirth of the sun as days began once more to lengthen and the light, therefore, was seen to overcome the darkness. This festival was associated with the Cult of the Unconquered Sun, or Sol Invictus, a sun god that held a place of honor as a principal deity in the Roman Empire. But it is the roots of Sol Invictus in far older Mithraic traditions that raise further questions about how pagan influences have defined Christianity.

Geertgen tot Sint Jans’s The Nativity at Night c. 1490, via Wikimedia Commons

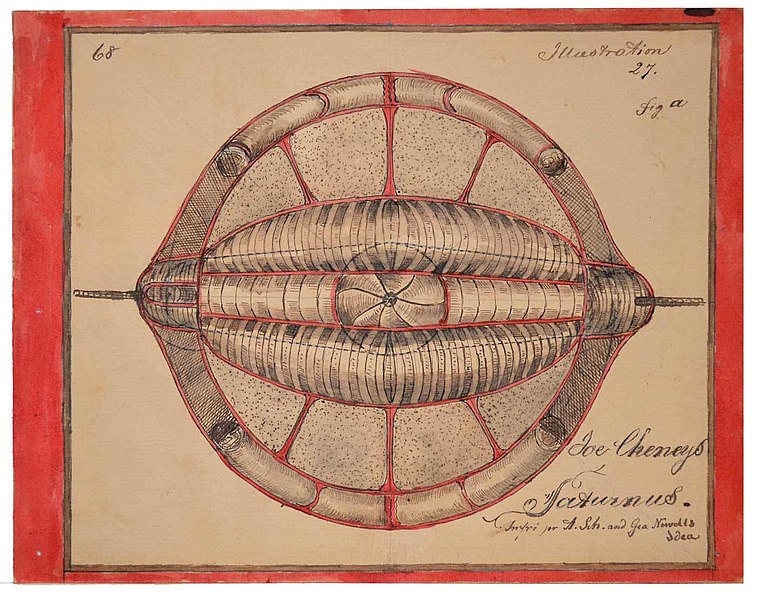

Stop me if you’ve heard this before. Pretty much everything about Christ and Christianity is actually derived from Mithraism and its central figure, Mithra. Born to a virgin on December 25th, Mithra too was visited by shepherds. In his life he traveled and taught and performed great miracles, gathering 12 followers before he sacrificed himself and ascended to heaven. Remembered as a messiah, his followers, who were baptized and observed a Eucharistic ritual meal, worshiped him on a day set aside as sacred: Sunday. Listening to this litany of similarities and knowing that Mithraism preceded Christianity by hundreds of years, many have been led to believe that Christianity was little more than a knockoff religion repackaging the Mithra narrative. Some suggest Jesus may have been an initiate of the Mithraic mysteries, and that his death and resurrection was nothing more than a reenactment of Mithra’s rebirth. Others go further and propose without evidence that there may not have been a real Jesus, as such, that his story was merely a retelling of Mithra’s. Are you still with me? Have you shut off skipped to another Christmas podcast? If you’re still listening, the truth of matter seems to lie somewhere in between the two extremes. Certainly Mithraic traditions predated Christianity. Indeed, they predated the Roman Empire. Long before his entrance into the Western world, the figure of Mithra appeared in India and Persia as Mitra, a marshal of peoples and binder of men in covenants and contracts (Laeuchli 74). Even in these earliest of iterations, he is associated with the sun, first as a kind of intercessor, mediating between the heavens and the earth, ensuring the rising of the sun and thus the success of agricultural endeavors. As the figure made his way into Persia and became Mithra and thereafter reached the West and became Mithras, he developed more martial qualities, and indeed his cult was eventually widely spread by soldiers (Hinnells). His association with the sun also developed to the point that, while he was depicted as a man, often killing a bull, he was also depicted as the very sun itself. Aside from any similarities, there are myriad pronounced differences from Christianity, and some have even argued—with no real support—that, rather than Christianity borrowing from Mithraism during the time of their competition for devotees, it was actually Mithraism that modeled itself after Christianity. While this is not well-supported, there is at least the possibility of it being true, for most of the similarities that are cited relate to the later Roman Mithraic traditions that developed contemporary to Christianity.

The question of who plagiarized whom—if the syncretism of religious traditions can even be called plagiarism—becomes moot, however, if it turns out that the similarities themselves aren’t actually there. For example, the date December 25th, which I’ve already argued in unsupported in the birthdate of Christ, may not actually have been universally accepted as Mithra’s birthdate either, as archaeological evidence indicates Mithra and Sol Invictus may have been considered separate deities, perhaps closely connected or even a dualistic manifestation of one divine being but certainly possessing their own identities. As for the virgin birth, some versions of the Persian Mithra were born to a virgin water goddess called Anahita, conceived either by the “milky fountain of immortality” or by some kind of incestuous relationship between the two of them that simply doesn’t make sense in a purely chronological, chicken-before-the-egg way. However, the Roman Mithras was said to have sprung fully formed from a rock, witnessed by two torchbearers that have somehow been distorted into shepherds for the purpose of forcing the comparison to the nativity. And while it is true that some ancient versions of the nativity have Christ born in a cave, none have him born of stone. Moreover, Mithra was never said to be a man traveling the land and imparting his wisdom as was Christ, and while there are plenty of works of art in Mithraic temples that have been construed by scholars as depicting Mithra performing some wonder or another, there are no testimonial stories of him performing such miraculous works as we have of Christ. Some of that art also portrays Mithra surrounded by twelve other figures, but these weren’t disciples or even men; they were the signs of the Zodiac. Meanwhile, their supposed Eucharist was essentially just a ritual meal, common in religious ceremonies, comprised of more than just bread and wine, and lacking any suggestion of the consumption of Mithra’s flesh and blood, which would of course make it not Eucharistic at all. Indeed it does appear that the Mithraic mystery cult engaged in ceremonial washings and baptism, and Mithra did have Sunday, the day named for the unconquered sun, set aside for him, but as can be seen, the lion’s share of these claims are either demonstrably false or dubious.

Relief depicting Mithras slaying a bull, via Wikimedia Commons

Likewise, doubt can be cast upon the assertion that Christmas trees were a heathen tradition. Like many others, I have smugly pointed to the book of Jeremiah, Chapter 10, verse 3, to suggest that Christians were hypocrites for putting up and decorating Christmas trees. It reads, “Thus saith the Lord, Learn not the way of the heathen, and be not dismayed at the signs of heaven; for the heathen are dismayed at them. For the customs of the people are vain: for one cutteth a tree out of the forest, the work of the hands of the workman, with the axe. They deck it with silver and with gold; they fasten it with nails and with hammers, that it move not.” How upsetting these lines can be to a God-fearing Christian at Christmastime. And as Jeremiah was likely composed hundreds of years before the birth of Christ, it would seem to be a clear cut case of pagan traditions incorporated into Christmas. But in fairness, with the context of the following verses, it is clear that Jeremiah is talking about the creation of idols carved from the wood of trees and then covered in precious metals. And what we know of the history of Christmas trees does not support an origin so far back in antiquity.

The tradition of decorating homes and churches with greenery in the winter has a long history, and it is closely connected to other traditions in other seasonal festivals, such as the lighting of candles, as it observes the same theme of light, warmth, and life persisting amidst the darkness, the cold, and the death present all around us in winter. In London, as early as 1444, it is recorded that a proto-Christmas tree was erected outdoors in the form of a maypole that had been adorned with ivy and sprigs of holly. So we do indeed see a secular basis for this tradition, but for true Christmas trees, we must look to Germany, where in that same century two legends grew. One told of a saint Boniface who foiled a pagan human sacrifice to Thor by felling the oak tree on which it was to take place and putting up a fir in its stead, the evergreen serving as a metaphor for eternal life through Christ. The other legend told of an apple tree miraculously blooming on Christmas Eve, a miracle that inspired others to claim they also witnessed trees inexplicably flowering on Christmas. These stories may also have been inspired by the so-called paradise plays that were popular on Christmas Eve. The plays dramatized the events of the Garden of Eden in Genesis with an evergreen tree standing in for the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil and apples tied to its branches to represent the forbidden fruit. Imagine that for a moment. Isn’t it the perfect precursor to the Christmas trees of today, festooned with red sparkling bulbs? The people eventually stopped putting on their paradise plays, but they kept the decorated trees, displaying them in public squares and eventually bringing them into the home. The practice became so popular that some municipalities actually passed ordinances limiting the chopping of trees and the number of trees people could have in their houses. And this tradition, in which again we might see pagan, secular, and Christian influences, spread from Germany the world over.

So it’s not such a cut and dry affair as some loudmouth atheists might present it. Yes, elements of Christmas may have derived from Mithraic traditions, but clearly some prominent mainstays—the nativity narrative, the Christmas tree—have decidedly Christian origins. And if the theme at the heart of the evergreen tree being displayed in the dead of winter owes something to more ancient and non-Christian traditions in the form of decorating with greenery, it shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise. The same can be said of the Mithraic celebration of dies natalis solis invicti, for neither was theirs the first midwinter celebration to mark the solstice, or solstitium, when the sun stood still. For an even more ancient forerunner, we must look to the celebration of Saturnalia in primitive Rome. Since at least the first century, and likely even longer, a festival was held by farmers to observe the conclusion of the planting season. Starting as a 2-day event honoring the god Saturn, the sower of seeds, as its popularity grew with the Roman Empire, it expanded, and like the Advent began earlier in the month and concluded in late December, near the solstice. Saturnalia appears to be the origin of the season’s merrymaking, for it was a time of great feasts, lavish banquets when social order was relaxed. In fact, the excesses of Saturnalia were so great that the notoriously extravagant and libertine Emperor Caligula even felt it needed to be reined in. So there appears to be a long and storied history to our Christmastime wassailing and inebriety. Other connections include, of course, decorating buildings with greenery, lighting candles, and even giving gifts, usually of candles, wax dolls, and caged birds. And Saturnalia is not alone as a precursor or contemporary midwinter festival with similar elements to Christmas. Other secular and pagan festivities include the Kalends, a civic celebration of the New Year during which people feasted, decorated buildings with greenery, gave gifts and even enjoyed the spectacle of parades. Then there is the decidedly Christmas Germanic celebration of Yule, an ancient name for the month of January that was synonymous with “festivities.” This celebration appears to have been related to Norse mythology, as Odin, the Yulefather, was said during this time to lead an army of the dead on a hunt, riding across the sky on an eight-legged horse. A more realistic but no less fun explanation is that Yule marked the end of harvest and therefore the beginning of the season for brewing beer, and so was a time for carousal, when in addition to feasting and burning a yule log in the hearth, many were known to “drink yule.”

Peter Nicolai Arbo’s The Wild Hunt of Odin, 1868, via Wikimedia Commons

So what we are talking about here is not plagiarism, as I so clumsily put it before, but a well-known phenomenon known as syncretism: defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “The amalgamation or attempted amalgamation of different religions, cultures, or schools of thought.” If Christmas, the Christian Christ Mass, blended purposely or organically with religious and cultural forms that preceded it, it is nothing that all its predecessors had not already done. As the Kalends grew in prominence, they adopted the traditions of Saturnalia, and even if we do not know the means of their transmission to other regions, we certainly see their similarities in the Yule festivities as well. And of course, we see them further appropriated by the Mithraic cult of Sol Invictus, and Mithraism is a serial offender in this regard. It has been called “wildly syncretistic… a bizarre mixture of primitive and more advanced cultural elements” (Laeuchli 77-78). In fact, some suggest that Mithraism’s success in spreading so far across the ancient world is owed specifically to the fact that people of other cultures, when exposed to his myth, were easily able to conflate him with other deities, solar and otherwise. He was identified with the Babylonian Shamash and Marduk as well as the Mesopotamian Bel, and then his cult folded in nicely with that of the Roman sun god, Sol Invictus. Then we have Christianity, which shared prominent commonalities with other so-called mystery religions, including the celebration of god’s birth, death, rebirth and ascension, and an emphasis on initiation in the form of baptism and, for a long time, secrecy, using the ichthus, or Christ fish as a kind of secret password or signal. Should anyone be surprised then that in the melting pot of religion that was Rome some blending took place? And should Christians be defensive at the suggestion or deny its truth? The answer to both should be no, in my opinion. If anything, a better understanding of the robust and many-faceted history of Christmas traditions just shows that this most wonderful of holidays belongs to Christian and non-Christian alike, that all of us can see in it a history and a theme of great value: the bravery of making light in the darkest time of the year, the hope of renewal, of the return of the sunshine and life springing forth again from a cold earth, a belief in resurrection in every sense. So rather than quibble over how each tradition started, instead of mocking others for what they see and value in the holiday, let us all take what merriment we can from it and kindle a fire of fellow-feeling in every breast. Merry Christmas to all!

Further Reading

Flanders, Judith. Christmas: A Biography. St. Martin’s, 2017.

Laeuchli, Samuel. “Urban Mithraism.” The Biblical Archaeologist, vol. 31, no. 3, 1968, pp. 73–99. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3210985.

Lincoln, Bruce. “Mitra, Mithra, Mithras: Problems of a Multiform Diety.” History of Religions, vol. 17, no. 2, 1977, pp. 200–208. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1062362.