The Diabolical Features of Spring-Heeled Jack

As we make our way through the dark nights of October, let us consider the disturbing and intriguing story of a Victorian-era bogeyman who has been portrayed variously as a mischievous spirit, a violent creature, a nefarious prankster, and an extraterrestrial being. Some commonalities with that far better known Victorian villain, Jack the Ripper, include that he was responsible for numerous violent assaults against women and that he was popularly given the same appellation, Jack, but this was certainly a different beast, as it were, entirely. From 1837 to the 1870s and on into the 20th century, London and its surrounding environs—as well as other English cities—were periodically haunted by an unsettlingly tall and dark figure who ambushed his victims in the dark of the night and was said to display various preternatural and even, perhaps, supernatural, abilities. Legends of this Jack were lost to history and not popularly known until the 1960s, when an editorial call for stories of extraterrestrial encounters prior to Kevin Arnold’s 1947 sightings were answered by one J. Vyner in an article called “The Mystery of Springheel Jack.” Vyner’s article focused on the various inconsistently reported details that indicated there was something weird about this figure, presenting a picture of a being with pointed ears and claws who could leap to great heights. In Vyner’s depiction, he wore a sparkling metallic helmet and tight-fitting suit, reminiscent of a spaceman, with a light affixed to his chest, as if it were Iron Man armor—and indeed it proved to be bulletproof! Moreover, his eyes glowed, and he fired a futuristic gas gun that sent his victims swooning. This is the image of the so-called “Spring-Heeled Jack” that became popular in modern times: that of an alien creature, likely stranded after a UFO crash, searching for refuge in 19th century England. But as researchers return to the original newspaper sources and other contemporaneous documents upon which all understanding of this figure must rest, they find that elements of Vyner’s depiction cannot be corroborated and likely were embellished to please his particular audience. One researcher, Mike Dash—whose work I relied on heavily in my episode on the disappearance of the Flannan Isles lighthouse keepers and whose thorough investigation into the Spring-Heeled Jack mystery will serve as my principal source in this episode—found no confirmation in contemporary sources for the cropped, animal-like ears or the sci-fi gas gun, and shows that the idea of a light attached to his chest was a simple misrepresentation of a report that he held a lantern up in front of his chest. Dash tracks all the different unnatural aspects attributed to this figure: superhuman leaping ability, slashing talons, a hide or suit of armor that proved impervious to bullets, and—far more disturbing than a gas gun—the reports that he spat fire! These attributes were not reported consistently in all of Spring-Heeled Jack’s appearances, but they appear consistently enough to warrant the consideration that this was no common attacker. So what was Spring-Heeled Jack? Is his a story of hoaxes in newsprint, as we have seen before, or of mass hysteria, as is a useful explanation of so many other phenomena? Or was he real? And if real, was he a creature out of nightmare or just a uniquely equipped human criminal? And if a mere man, who was this steampunk villain?

We’ll begin on a dark winter’s night in February 1838, east of London in the village of Old Ford, where what would become Spring-Heeled Jack’s most famous attack is about to occur outside the little cottage of the Alsop family. The hour approached 9 p.m. when 18-year-old Jane Alsop heard the bell at their gate ringing forcefully. She went to the door and looked out across the dooryard, seeing the figure of a man standing in the darkness at the gate. What’s the matter, she inquired and asked him to stop ringing the bell so violently. The figure identified himself as a policeman and said, “For God’s sake, bring me a light, for we have caught Spring-Heeled Jack here in the lane!” Jane rushed to fetch a lighted candle and hurried across the dooryard with it. When she handed the candle to the shadowy figure, she saw that he wore a long cloak, and instantly, he threw aside the cloak, revealing the garments beneath: a tight-fitting white suit of a material that appeared to be something like oilskin. He held the candle to his chest, illuminating himself for Jane to see: a hideous face, with diabolical features. He wore a helmet of some sort, his eyes shone like red fire, and he vomited blue-white flames from his mouth. Springing at her, he seized Jane by her dress and gripped the back of her neck. His fingers seemed to terminate in metal claws, and forcing her head under his arm, he proceeded to slash at her clothing. Jane shrieked and wrenched herself out of his grasp, dashing back toward the front door of her house. Just as she reached the front steps, though, Jack was on her again, ripping out her hair and slashing her arms, shoulders, and neck. Just then, her sister rushed out and pulled her from his clutches, and the alarm was raised in the house. The family rushed upstairs to shout for help from the police, and there they claimed to see the attacker fleeing across a field. Afterward, Jane’s father, having heard his daughter’s story, went out to his gate, expecting to find the cloak that the villain had thrown off still lying on the ground, but there was nothing there, leading him to suspect the attacker had not been alone.

Spring-Heeled Jack, depicted making off with a young lady victim, via Wikimedia Commons

Hearing this tale, what stands out, aside from the terrifying aspect of the attack, is the fact that this attacker lured Jane out by saying he was a policeman and that he had caught Spring-Heeled Jack. Therefore, he must have assumed that the name was familiar to the Alsop girl. So where did this character make his first appearance and what legend had already grown up around him by the time of the Alsop attack? First mention of the attacker appears in London newspapers in December of 1837, and strangely, his first appearances bear little resemblance to the specter as he later became known. It was said that in September the previous year, he had appeared in the village of Barnes as a white bull, although it was believed he was a ghost or devil merely assuming that form. Over the course of a few months, when he appeared to attack people, both men and women, he was variously described as, once again, an animal, such as a bear, or as a ghost or devil. It is unclear whether these latter terms were used rather more figuratively than literally. Yet in some of these early appearances, elements of his eventual depiction emerge: He is described in some instances as wearing mail or armor, and in others as wielding iron claws. Even his ability to leap, which we don’t really see evidenced in the Alsop testimony, was well established by then, with accounts of the figure scaling the walls of Kensington Palace to dance on its lawns. His preternatural leaping ability was attributed to his having springs in his boots, leading the newspapers to dub him Spring Jack, a nickname that had evolved quickly to Spring-Heeled Jack. And Alsop was not even the first to associate a blue fire with this attacker, as one young woman of Dulwich had been accosted by a ghost in a white sheet enveloped in blue flame. With these reports multiplying in newspapers over the course of those several months, it is safe to say that by the time the shadowy figure approached the Alsops’ gate that February night, the idea of a devilish attacker named Spring-Heeled Jack lurking about in darkness to pounce on innocent young women was widespread and causing a veritable panic.

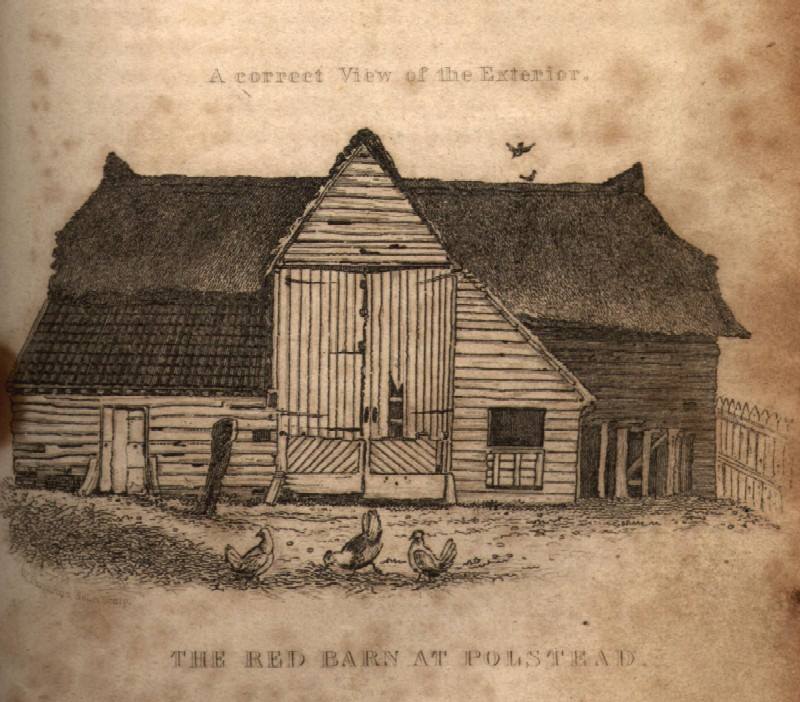

After the Alsop attack, Lambeth-street police office undertook an investigation headed by one James Lea, a renowned detective. Lea had found some fame ten years earlier while investigating the sensational Red Barn Murder. This case revolved around a young couple, William Corder and Maria Marten, who were much disgraced in their community—he for his philandering and swindlery, and she for her promiscuity and bearing of bastard children. They made plans to meet at a red barn and elope, but Maria’s family grew suspicious when she never wrote to them, despite the excuses William made in his letters. Then, perhaps on the basis of a dream his wife had, Maria’s father searched the red barn and found his daughter’s corpse. Detective James Lea had done the police work of tracking down Corder in London, confronting him with the charges, and searching his new residence, where he discovered some pistols that may have been the murder weapons and turned up some letters Corder had written claiming Maria was living with him and happy, evidence that helped to condemn William Corder to the gallows. Ten years later, and Lea found himself working another sensational case.

The Red Barn, scene of the crime, via Wikimedia Commons

Upon interviewing the residents of Old Ford, Lea found that this figure, or someone matching his description, had been haunting the area for a month, wearing a cloak and springing out at passersby in the lanes to frighten them, and some reports do indeed remark upon his agility in fleeing from those who had pursued him. Over the course of Lea’s investigation, he would come to the conclusion that this assailant need not necessarily have been a demon out of hell, as he inquired at the London Hospital and observed experiments that showed a man could reproduce the fire vomiting effects that Jane Alsop had described by blowing alcohol and perhaps other ingredients, such as Sulphur, into a flame, which of course the Alsop girl provided for her attacker. Moreover, he had suspects. When the Alsops cried for help from their windows, a trio of men from a nearby pub answered their call and reported encountering a cloaked man who told them a policeman was needed at the Alsop’s cottage. Another witness, James Smith, a wheelwright who at the time of the Alsops’ cries for help had been carrying a wheel up the lane, said he ran into two local men, Payne, a bricklayer, and Millbank, a carpenter. Smith described Millbank as being dressed all in white, white hat and shooting jacket, which could have been mistaken by Jane for the tight white oilskin and helmet she believed she had seen. What’s more, Smith asserted that, later that night, recognizing him as the man they had passed in the lane, Millbank asked him, “What have you to say to Spring Jack?” Then a shoemaker, Richardson, who had been on the same street and confirmed seeing Millbank and Payne there, claimed he had also seen two others, young men, one in a cloak, joking about Spring-Heeled Jack being in the lane.

So we have contradictory testimony from three sources--and indeed, because of this uncertainty, no one was ever charged with the crime—but all of these witnesses would seem to agree that the Spring-Heeled Jack in Old Ford that night was nothing more than a man or boy who thought the violent assault on Jane Alsop little more than a jest. This agrees well with Detective Lea’s assessment that this was a local criminal, for he had been reported in the area and apparently, as Lea pointed out, the perpetrator knew the family, as he seems to have called out to Mr. Alsop at some point, perhaps while at the gate. If this Spring-Heeled Jack were a resident of Old Ford, could he possibly have been the same assailant troubling so many villages in the previous months, ranging all over Isleworth, St. John’s Wood, Brixton, Stockwell, Vauxhall, Camberwell, and elsewhere? And was he the same Spring-Heeled Jack who, only five days after appearing at Jane Alsop’s gate, knocked on a door in Whitechapel and dropped his cloak to scare the wits out of a servant boy? And three days after that, could it have been the same man who waylaid the Scales sisters in an alley in Limehouse, once again wearing a cloak and some kind of headgear—described as a bonnet here rather than a helmet—throwing off his outer garment, lifting a lantern before him and spitting blue fire from his mouth into Lucy Scales’s face? Perhaps… perhaps it was simple recklessness to perpetrate his crimes not only in surrounding villages but also in his own neighborhood. But it may be impossible to tell, for already there were confirmed reports of copycats, so all of these must be considered dubious. In March, a man attacked the proprietress of a public house with a club, announcing he was Spring-Heeled Jack; a cloaked man assaulted a woman in Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields, slapping her face; and two cloaked men, who had blackened their faces, frightened a child. A young man in Kentish Town was let off with a warning after running around with a mask and blue paper in his mouth to approximate the fire of other reports, and another man was fined for going about in a mask and sheet. Meanwhile, a blacksmith in Islington saw in this panic a perfect opportunity for sexual assault and was charged with crimes against several women. And though most of these have little or nothing in common with the previous attacks, newspapers did not hesitate to print headlines announcing that Spring-Heeled Jack was out and about in their neck of the woods. So the name became a catch-all for any person going about in costume to scare pedestrians and grope young women.

Spring-Heeled Jack, leaping a gate, via Wikimedia Commons

After 1838, the specter of Spring-Heeled Jack disappeared for more than thirty years. Therefore, it is surpassingly unexpected that the figure would reappear over the course of multiple flaps in the 1870s and beyond. In early October 1872, the so-called “Peckham ghost” made his first appearance in that village. The term likely used in the metaphorical sense of a phantom figure, but perhaps also in reference to the ghostly appearance of this white-clad figure, this “ghost” made a habit of jumping out at women in roadways and rising up menacingly from behind fences to startle unsuspecting passersby. This figure’s costume was decidedly less sophisticated, a dark cloak lined in white so that he need only throw his cloak open for the desired effect. But still, some reports suggested the presence of fire around his face and the ability to leap high fences in a single bound, leading to the old speculation that his boots were rigged with springs or perhaps had soles of India rubber, which I suppose in English imaginations of the time had properties akin to flubber. A man was accused and held on charges of being the Peckham ghost, but appearances continued while he was in custody, so again, no one suspect proved a believable culprit for all the incidences. Then at the end of that year, another “ghost” scare has been subsequently linked with the legend of Spring-Heeled Jack, this time in Sheffield, the farthest flap from London at the time at some 227 kilometers to the northwest. This appears to have been a tall man in a classic ghost costume: a simple white sheet. But the fact that he is described as being swifter and more agile than a normal man and was reported to have jumped over walls and gates has led to his being linked with old Jack. It seems to be, however, that he, and perhaps many others tenuously identified as Spring-Heeled Jack, may have only been an early practitioner of free-running, the sport now called Parkour.

Perhaps the boldest iteration of Spring-Heeled Jack sprang up in 1877 at a British Army camp at Aldershot to bound around sentry boxes and powder magazines, dodging bullets and slapping guards. It’s said that this Jack made no answer when the sentries saw him approaching and demanded he identify himself. With astonishing speed, he came close enough to slap some of the sentries’ faces with a hand that felt cold, like that of a corpse, and then hopped off toward a nearby cemetery. The guards in more than one instance gave chase and fired their weapons after him, to no avail. This has added to the legend that Jack was bulletproof, though the original reports could actually just be indicating that the guards missed their mark. That same year, Spring-Heeled Jack was reported by certain publications to have appeared numerous times, once climbing the Newport Arch, an ancient Roman landmark, with bullets fired by locals bouncing off the strange hides he wore. But ’77 was not his last hurrah, for 11 years later, during the Ripper murders, he showed up in Everton, in Liverpool some 288 kilometers from London, crouching in church steeples. Then into the 20th century he ventured, showing up again in Everton in 1904, leaping over rooftops in front of hundreds of witnesses. This last appearance, however, came with something of an explanation. It seemed that this scare actually originated with a supposed haunted house known to have poltergeist activity. The place was so famous in those parts that crowds of Liverpudlians used to gather outside in fearful expectation of seeing the ghost within. Add to this the presence of a local man who suffered from some mental imbalance who used to run around rooftops shouting about his wife being a devil, knocking bricks and mortar down on baffled onlookers, and you had a perfect recipe for a leaping ghost scare. With such an explanation in this flap, one wonders whether all the previous flaps might be similarly explained.

Spring-Heeled Jack among the headstones in a cemetery, via Wikimedia Commons

Certainly there appears to have been some hysteria involved in many of the reports. Newspaper reporters themselves were skeptical at first, back in 1837, suggesting these were just the kinds of chilling tall tales passed around by servant girls, and in the few instances in which they did any real investigation, there seemed a dearth of first-hand witnesses. On some occasions, the ghostly beasts that had been reported lurking on the streets were simple cases of misidentification: a pale-faced cow or a white police horse became a ghastly demonic bull or bear or a hoary devil. Even the report of Jack dancing on the lawns of Kensington Palace was actually a re-imagining of something far less nefarious that happened 15 years earlier. And during the thick of the panic in January 1838, The Morning Herald’s investigation turned up plenty of people repeating the stories of Spring-Heeled Jack, but no one who had actually seen him firsthand. The reporter found himself chasing after empty leads, tracking down people who were said to have been injured by the phantom attacker only to have them say it hadn’t happened to them personally and send him on looking for someone else to whom it had happened. As Mike Dash has pointed out, this is a textbook example of an urban legend.

However, there do appear to be verifiable reports of some attacks, such as in the Alsop case, where we also have some very human suspects, and years later at Aldershot, where again it seems a human man may have perpetrated the attacks on sentries as a prank. It was reported that an unknown individual had earlier been stopped entering the camp carrying a carpet bag that could have contained a costume but that he was allowed to enter when he claimed to be a soldier. And there is some indication that the Aldershot Jack may have indeed been a soldier, for after being shot at, he ceased his nocturnal games until such time as the soldiers had been ordered not to waste any more ammunition firing at him, at which time he resumed his escapades. Only a soldier stationed there would have been aware that there was no further risk of being gunned down. And while of course the Alsop attack was a serious act of violence, as were all the sexual attacks associated with Spring-Heeled Jack, there is plenty of precedent for the notion that many attacks may have just been undertaken as pranks, as in Aldershot. All the way back in 1803, a ghost was said to be haunting the lanes of Hammersmith. His clothing, if nothing else, was described in terms quite similar to Jack’s, as white like a sheet and sometimes similar to an animal’s hide. Eventually a man encountered him, shot him, and was tried for his murder when beneath his costume he turned out to be a respected member of the community just out scaring people for a laugh. And the idea that Spring-Heeled Jack may just be a prankster, or several pranksters, was considered even in early 1838, as several newspapers reported on rumors that a group of bored noblemen were behind the attacks, performing them as part of a wager. One particular young nobleman, The Marquess of Waterford, Henry Beresford, known to drink heavily and enjoy a practical joke, was among those suspected of being involved in the wager, but there is no concrete evidence to support this speculation.

Henry Beresford, 3rd Marquess of Waterford, via Wikimedia Commons

Hard evidence, however, is not something that 19th century newspapers always require before putting a story into print, as we have seen before, most recently in our examination of the phantom airships in America. London newspapers helped spread this panic by printing second hand accounts of the attacks, by calling him a ghost and a devil, and by dubbing him with the catchy name Spring-Heeled Jack. And some less scrupulous newspapers, such as the Illustrated Police News, which reported a number of sensational encounters with Spring-Heeled Jack in 1877 that no other sources corroborate, may have been fabricating incidents out of whole cloth. And the secondary literature also is rife with embellishment and falsification. Mike Dash has done the hard work of fact checking other writers who had researched the topic before him, and one of them, Peter Haining, seems to have manufactured stories for the specific purpose of confirming the theory that the Marquess of Waterford was behind the crimes. He tells of an attack on a servant girl named Polly Adams and has her describe her attacker as a laughing nobleman with protruding eyes like those of Henry Beresford, when no contemporary source has been turned up to confirm that such an attack ever occurred. Likewise, to one appearance of Jack that does appear in newspaper reports, he added the specific detail that a witness had identified a crest with a gold filigree “W” stitched into Spring-Heeled Jack’s cloak. This report is often repeated today as support for the notion that Waterford was behind the crimes, but there is no indication that it ever happened beyond Haining’s claim. And Dash has proven that Haining lacks all credibility, as he completely invented one encounter: the murder of a prostitute named Maria Davis that he attributes to Spring-Heeled Jack. Haining provided a woodcut illustration that he claims shows the recovery of Davis’s body from a ditch, but Mike Dash tracked down this woodcut to discover that it only depicts someone gathering water, not recovering a corpse. With distortions as shameless as these obscuring the truth here, it’s hard to tell what can be trusted.

The picture Haining misused, via Morgue of Intrigue

Nevertheless, while some of the attacks may have been contrived, and some may have been mere imitations, there must have been some original. A legend does not spring up from nothing, does it? And despite all the different variations on his appearance, the different modus operandi, far-flung settings and disparate time spans, one still sees similarities, a pattern that is hard to dismiss. Even outside of the UK, there have been other, similar encounters, and it is hard to imagine that the legend of Spring-Heeled Jack would have spread so far, especially since the newspapers there never made such a link. In Georgia, in 1841, a man dressed as the devil attacked and robbed a woman, and when confronted, he swelled and emitted smoke, pronouncing himself the Prince of Darkness before being shot to death. In Cape Cod, more than thirty years after his final appearance in England, a phantom called the Black Flash skulked around Provincetown with flaming eyes, spitting fire into his victims’ faces, laughing when shot at, and springing easily over 8-foot fences. In those same years, during World War Two, a “Spring Man” was known to hop down the darkened streets of Prague after the German-imposed curfew. Then the fifties saw a similar figure appear in Baltimore, clad in a black cloak and leaping onto rooftops. In fact, to a modern audience he might sound like a proto-Batman, and indeed, despite the terror he struck in many, he also appeared as a heroic figure in Victorian Penny Dreadfuls, terrifying villains with his preternatural leaps and acting the part of the outlaw hero, an anti-hero like Robin Hood. So one could certainly see Batman, the vigilante with acrobatic skills and a frightening persona, as being part of the same tradition as Spring-Heeled Jack. Is this then something universal, an archetype, a folkloric tradition like others we see appearing independently in different cultures? Or is it just testament to the eternal appeal of dressing up and leaping out to scare people? At this time of year, I lean toward the latter. Happy Halloween!

*

Further Reading

Dash, Mike. “Spring-Heeled Jack: To Victorian Bugaboo from Suburban Ghost.” Fortean Studies, vol. 3, 1996, pp. 7-125. mikedash.com, docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/7bb090_e0f718375aa54f789586c062f29dd204.pdf.