Blind Spot: The Terrible within the Small; or, The Fabrication of the Learned Elders of Zion and the Forgery of Their Protocols

In this short companion piece to my previous post on the Blood Libel, it turns out I have a bit more to say about that topic, for unbeknownst to me while I wrote that piece, the ancient accusation that Jews engaged in ritual murder was actually in the news. For any who doubt that these grossly absurd and malicious myths could possibly be given any credence in the modern era, consider the fact that the Russian Orthodox Church, in conjunction with Vladimir Putin’s regime, have just revived the blood libel in the form of a claim that in 1918, Tsar Nicholas II and the rest of the Romanov family—including little Anastasia, despite persistent rumors—were not just executed but were ritually murdered. While they may not have named Jews as the ritual murderers, Russia’s long history of dubiously associating Jews with Bolshevism makes the subtext of the accusation clear, and Jewish organizations in Russia and abroad have expressed not only concern but outrage.

That the blood libel would rise again in Russia, of all places, is sadly not surprising, for Russia has a long history of brutally oppressing the Jews. Jews had been forbidden to enter Russia since the 15th century, but after 1772 and the first partition of Poland, they came under Russian rule regardless. Fearing the competition of Jewish merchants, Jews were restricted to living only in certain border territories, later called the Pale of Settlement. Tsars consistently struggled with the question of how to deal with this foreign element in their kingdom. Some made attempts to integrate them, such as Tsar Nicholas I, who did so by imposing forced conscription, requiring all Jews to serve 25 years in his armies on the assumption that this would acculturate them nicely. Nevertheless, Russian Jews preserved their cultural heritage and thus their “otherness.” By the 1860s, fears of Jewish plots began to arise, and by the 1880s, we see the first of the Russian pogroms, usually around Easter, when the story of Jews murdering Christ inevitably stirred ire and likely rekindled the blood accusation as well. Moreover, Jews who had built any measure of affluence for themselves despite the restrictions placed on them appear to have inspired envy and hostility among poor Russians, who invariably incited these targeted riots by starting brawls. After the pogroms of the 1880s, the Russian state increased its systemic repression of the Jews, limiting their economic privileges, restricting their further settlement, blocking their admission to higher education and eventually expelling them from Moscow. Russian Jews responded with a further diaspora, fleeing for friendlier lands, and among those who stayed, many joined the Zionist movement, justifiably yearning for a homeland all their own, while others became radicalized, swelling the ranks of revolutionary movements, which of course only exacerbated mischievous lies that all Jews conspired together to overthrow the Russian monarchy, or perhaps on an even grander scale, to conquer the world. This is the story of one such conspiracy theory and the documentary evidence supposed by many—even today, despite all evidence to the contrary—to prove it true, the story of what has proven to be a tenacious historical blind spot for many. Thank you for listening to The Terrible within the Small; or, The Fabrication of the Learned Elders of Zion and the Forgery of Their Protocols.

1905 map showing percentage of Jews in the Pale of Settlement, via Wikimedia Commons

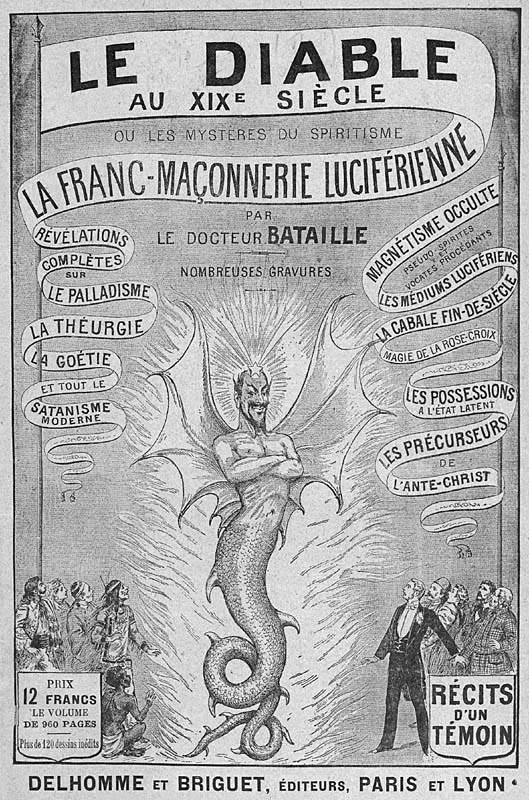

Conspiracy theories claiming that all Jews worked together internationally to advance some nefarious agenda were not new. As I mentioned at the end of my episode on the Blood Libel, the idea was present in medieval Norwich in Thomas of Monmouth’s claim that the converted Jew Theobald had revealed to him a great council of Jewish royalty and leaders who convened in France to decide which country would host their annual ritual murder. And in 1348, the very same year that the Black Plague appeared, so did accusations that the disease had been spread by Jews poisoning wells as a means to destroy Christians. However, the 19th century saw a transformation of the conspiracy theories about the Jews. Rather than depicting them merely as anti-Christians, they began to be seen as a secret cabal hell-bent on world domination. Now this was a role traditionally played by Templar Freemasons and the Bavarian Illuminati in transnational conspiracy theories, but after the Revolution of 1848, in which Jews were active, these conspiracies to overthrow the status quo and supplant it with something different, and therefore frightening, began to be blamed on Jews as well as Freemasons. In the 1860s, a number of books appeared that promulgated these myths. Posing as an English aristocrat, Hermann Goedsche published a novel called Biarritz in 1868 in which he has a cabal of powerful Jews meeting secretly in a Prague cemetery to discuss their vast scheme to subvert the governments and religions of the world to their eventual gain. This scene, it turns out, was baldly plagiarized from an Alexandre Dumas novel depicting Cagliostro meeting with the Illuminati to discuss the Affair of the Necklace, but it clearly indicates the kind of intrigue attributed to Jews in those years.

In Russia the next year, we see Iakov Brafman’s Book of the Kahal, published in Minsk, that set forth the claims that following the much maligned Talmud, Russian Jews had learned to hate Russia’s culture and people and were actively conspiring to topple the Orthodox Church. Then the religious enmities and the lust for secular power attributed to the Jews finally came together in one especially vitriolic accusation. One Sergei Nilus published a book in 1903 entitled The Great within the Small. Due to his role in the bringing forth of a monstrous and seemingly immortal conspiracy, Nilus has to posterity become a much mythologized character, a monk and a séance-leading mystic—which considering the preoccupation with occultism and spiritualism at the tsar’s court would not itself be absurd if it were accurate. In truth, Nilus was from a noble family and had practiced law for a time, but after retiring, he became enamored of the apocalyptic strain of the Orthodox faith, and eventually established his own brand of visionary religion. He gained some fame for himself when, in the first edition of The Great within the Small, he claimed to find and translate the writings of a famous Russian saint. However, it is in the second edition of The Great within the Small, which bore the subtitle The Advent of the Antichrist and the Approaching Rule of the Devil on Earth, that his anti-Semitic conspiracy theory takes clearer shape. In it, he outright asserts the existence of a worldwide Judeo-Masonic conspiracy not only to overthrow Christian states and establish their own global dominion but also to raise up a Jewish world leader, a tyrant who would be the Antichrist. And as proof of their machinations, he offered as an appendix another document that had somewhat mysteriously come into his possession: The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, which purported to be the minutes of a secret meeting among the masterminds of a vast Jewish conspiracy. In brief, the Protocols reveal that Jews the world over have been colluding a long time to depose all monarchs, overthrow all governments, and corrupt all religions. Commanding the absolute loyalty of all Jews and marshalling the secret forces of the Freemasons and other secret societies, they bring about their goals by inciting populist revolutions and advancing liberalism, which leads invariably to socialism, and thence to communism before finally descending into anarchy and the complete destruction of civilization.

Sergei Nilus, via Wikipedia

Nilus offered little help in the way of determining the origin of this manuscript, offering a variety of contradictory stories. First, he asserted that a friend in the Okhrana, or Russian secret police, took it from a whole book of protocols found in a Zionist stronghold in France. In a later edition, he clarified that they had been stolen by the wife or lover of a Masonic leader in Alsace from his iron chest. Then in the 1917 edition, Nilus further explains that these were essentially the minutes of the first Zionist Congress in Switzerland in 1897, but of course, that was not a secret meeting, but rather a very public one, and the Protocols were certainly not items on the agenda there. As the story progressed, then, Nilus adjusted his story to assert that the Protocols had been stolen from the home of Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism. Regardless of which of these stories Nilus actually believed, if any, we do know that the document had been in circulation before he got his hands on it, as it was published in part by a Russian newspaper in 1903, to little notice. Such was certainly not the case after the publication of Nilus’s The Great within the Small. There is reason to think that Tsar Nicholas II himself was swayed by the Protocols. Previous to their advent, he had shown some inclination to give in to liberalism and modernization, for in 1905, with the October Manifesto, he limited his powers and established a parliament and a constitution, but afterward, he thwarted it by constantly dissolving it and enacted a broad program of anti-Jewish propaganda in conjunction with the Orthodox Church. Pogroms in that year, as the Protocols became widely read, ran rampant, claiming the lives of 3,000 Jews. Most of these pogroms were incited by the state itself through its provocateurs, the Black Hundreds, a proto-fascist group that stirred the rumor that the revolution was a Jewish conspiracy to overthrow the tsar. And after the Bolsheviks had seized control and executed the Romanov family in 1918, a new edition of the Protocols was widely distributed among the tsarist counterrevolutionary White Army. It was essentially their bible, proof that those they fought were pawns of evil Jews hell-bent on the overthrow of the world. White Army soldiers went so far as to read the Protocols aloud to any illiterates who needed indoctrination, and during the course of the next couple years, they massacred somewhere around 120,000 Jews.

It was after all of this carnage, and after White Army emissaries had distributed the Protocols abroad at the Versailles Peace Conference, thereby commencing the long history of the Protocols’ publication outside of Russia, that voices of reason began to cast doubt on the document. In May of 1920, Dr. J. Stanjek published an analysis of the text of the Protocols that proved it was plagiarized in part directly from Hermann Goedsche’s Biarritz, who, if you recall, had himself plagiarized Dumas, making the Protocols essentially a plagiarism of a plagiarism. And shrewdly, Stanjek also predicted that other portions of the text were likely plagiarized from a French source, as they seemed a direct criticism of Napoleon III. However, this exposé was not enough to halt the spread of the Protocols, which continued to terrify and convince such memorable personages as Henry Ford in America and Winston Churchill in England.

Then, sure enough, in 1921, a foreign correspondent for the Times of London stationed in Constantinople was approached by a former operative of the Okhrana in exile with a copy of a French book published in the 1860s. This book, Dialogue between Machiavelli and Montesquieu in Hell by Maurice Joly, was a thinly veiled satire of the policies and schemes of Napoleon III, and as Stanjek predicted, proved to be the source for most of the rest of the Protocols, indicating that the destructive little pamphlet was just a patchwork, a palimpsest of previous works, all fiction, that originally had nothing to do with the Jews.

Maurice Joly, via Wikimedia Commons

As scholars have since theorized, reactionary conservative members of Tsar Nicholas II’s court with connections to the Okhrana secret police—Pyotr Rachkovsky, head of the secret police, has been named—likely conceived of the Protocols as a means of turning the Tsar against the liberal influences in his court. Thus they turned to their propagandists in France, and some have identified the forger Mathieu Golovinski as a likely candidate for the Protocols’ plagiarism. Golovinski started his career manufacturing evidence for the state police and continued with the Orthodox Church’s Holy Synod, producing fake news articles for that organization’s propaganda campaign against modernization, liberalism, socialism, and, of course, what many already saw as Jewish influence on Russian society. And later in his career, while in exile in Paris, writing false stories to be planted in the foreign press, it is theorized that Rachkovsky or some conservative member of the Tsar’s court, or perhaps one of their representatives in the Okhrana, tasked him with creating a document that would appear to be proof of a Jewish plot to modernize and liberalize Russia to terrible ends, all for the sole purpose of scaring the Tsar into a firmer and more conservative rule.

With the exposure of the Protocols as nothing more than a plagiarized forgery as early as 1920, one would think that the distribution and influence of the document would cease, but on the contrary, The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion has become one of the most widely translated and distributed texts in the world. In Germany, Joseph Goebbels saw it as a useful tool of propaganda, and Adolph Hitler, seeming to genuinely believe it, used it extensively as the basis for his whole worldview during his rise to power, thus eventually providing a pretext for the Holocaust. Even after a Swiss court declared the Protocols false in 1935 and the U.S. Congress declared them fraudulent in 1964, they continued to be brought forth. The Ku Klux Klan, unsurprisingly, continued to distribute the document, and in 1968, an Islamic organization in Beirut published hundreds of thousands of copies in multiple languages. New editions appeared in Egypt and France in 1972, in India in 1974, in America in 1977, and in England in 1978. The late 80s saw its publication in Japan and as part of the charter of Hamas. The early 1990s saw the Protocols pop up in Mexico and Turkey and again, coming full circle, being published once more in Russia. And in the 2000s, they appeared in print in Lebanon and on Arab television in the form of a serial adaptation. And it is still touted and given credence today by white nationalist and neo-Nazi groups as well as by conspiracy theorists like David Icke. It seems that, for the powers of intolerance and fear, the Jews are simply too tempting a target of scapegoating, for not even empirical evidence and plain logic can dissuade the believers in ant-Semitic conspiracy. When it is pointed out to them that the Protocols have long been known to be a plagiarized forgery, these hateful believers reverse the logical conclusion and claim that, clearly, the Jews must have then taken their plans from this forgery, plagiarizing this plagiarism of a plagiarism. Why? Because it confirms their fear and resentment of Jews and therefore must be true. When the truths we’ve managed to find in the past are ignored by those who purposely wear blinders, then it comes as no surprise that blind spots such as these threaten to send us back to the Dark Ages.

Images from various editions of the Protocols, via University of California, Santa Barbara

Images from various editions of the Protocols, via University of California, Santa Barbara

Images from various editions of the Protocols, via University of California, Santa Barbara

*

My principal sources for this episode were A Lie and a Libel: The History of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion by Binjamin W. Segel and the graphic history The Plot by Will Eisner, which I highly recommend and which you can find a link to on the website’s reading list.