Blind Spot: The Loss of Theodosia Burr Alston

In the last installment, I told the story of the Trial of the Century at the dawn of the 1800s, a murder mystery with Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr at its heart, defending an innocent man against awful calumnies. Despite winning their client an acquittal that the public generally praised as justice, a myth has arisen around the trial suggesting that Burr and Hamilton set a guilty man free, a legend helped by the fictional account of the Quakeress boardinghouse-keeper’s wife, Mrs. Ring, confronting the men before the courthouse to curse them for their part in freeing the murderer of her cousin, Elma Sands. This is an apocryphal tale produced by a relative of the Rings in a novel years later, but it has done much to shape the memory of the event, and when one considers the subsequent hardships and tragedies suffered by the supposedly cursed men, the tale certainly gives one pause. The troubles of Aaron Burr, in particular, grew and compounded over the next decade until he was dealt his most grievous blow. This is the story of that misfortune: the Loss of Theodosia Burr Alston.

At first, following the Weeks Trial, things went splendidly for Burr. His gambit of forming a bank masquerading as a municipal Water project brought a lot of merchants and middle class voters into the Democratic Republican fold, and his tireless canvassing ended up getting his party’s slate of candidates elected. In turn, their man, Thomas Jefferson, took the presidency, and Burr himself took the Vice-Presidency. After that, however, it was all downhill. Jefferson shut him out, and four years later sought to replace him. Burr thought he would run an independent campaign and poach votes from both parties, but during the course of that bitter presidential election, his old nemesis, Alexander Hamilton, worked industriously to ruin him politically. Eventually, vague rumors of Hamilton disparaging him to a group of Federalists over dinner, with hints of “despicable” accusations being made, led Burr to challenge Hamilton to their famous and fateful duel. And the calculated letter Hamilton left behind indicating his intention to purposely fire into the trees because of his disapproval of dueling proved to be the mortal wound from which Burr would never recover. His chances in the election were ruined, and the authorities were actually considering murder charges, so Burr, though still the Vice President, fled New York like a common criminal.

Duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, via Wikimedia Commons.

He fled to South Carolina, where the apple of his eye, his daughter Theodosia, waited to take him in. Theirs had always been an exceedingly close relationship. Burr found his girl to be as intelligent and discerning as any man, and in a departure from common attitudes of the time toward women, he supported her in her education and all her intellectual pursuits, encouraging her to read the writings of early feminists such as Mary Wollstonecraft. Indeed, their relationship was so close that some believe3d it unseemly, and it has been suggested that the “despicable opinions” expressed by Hamilton may have been imputations that Burr’s relationship with his daughter was incestuous. Theodosia lived with her husband, Joseph Alston, a South Carolina state congressman, and when Aaron Burr fled New York to stay with them, her son, named for his grandfather, was a precocious two-year-old who brought great joy to the beleaguered Vice President.

When the charges against him had been dropped and his term of office ended, Burr went westward. Within a couple years, his Democratic Republican ticket mate, President Jefferson, brought him up on charges of treason, as it was alleged that Burr had planned to build an army and seize land in the Southwest and Mexico, forming his own country. The truth of these charges, however, is debatable, and the whole affair would perhaps require its own episode to do it justice. Suffice it to say that while Burr beat the charges, with Theodosia at his side supporting him through the entire affair, his reputation would never recover, and thereafter he chose to live in exile and poverty in Paris. While abroad, he had Theodosia act on his behalf in all matters, and Aaron Burr would not return until 1812, when he finally came back to New York to resume his practice of the law.

But Fortune was not through with Burr. That year, while his son-in-law was running for governor of South Carolina, his grandson died of a malarial fever. In great despair, with her health suffering from the grief and stress, Theodosia boarded a pilot-boat–built schooner called the Patriot, a former privateer that had stowed its guns below decks for this journey, making herself vulnerable to attack. On this vessel, Theodosia set sail for New York to seek the comfort of her father. Burr came to the waterfront to meet her upon her arrival, but her ship did not appear at the expected time. Day after day, he paced the docks, and night after night, he wrote increasingly desperate letters, corresponding with the equally distraught Joseph Alston. Eventually, Alston, who won the governorship, had to accept that his wife had been lost at sea, and in his grief, he grew ill and died himself. Aaron Burr would live almost another quarter of a century after Theodosia’s disappearance, and if one believed that a curse really had been placed on him after the Weeks Trial, one cannot really imagine it heaping more calamity and heartbreak on him than this. For the remainder of his life, he was forced to hear and contemplate many theories as to what befell his poor, grieving daughter.

Reproduction of original John Vanderlyn portrait of Theodosia, via Wikimedia Commons.

The thought of his daughter drowning when her ship was caught in rough weather or struck broadside by a wave was surely bad enough. Worse were the whisperings that the Patriot had been taken by pirates, as how, then, might his beloved Theo have spent her final moments? What certainly made the thought more unsettling was its plausibility. Burr had been told that along the coast of North Carolina there lurked bands of scavengers called Wreckers or Bankers because they preyed upon the wrecks of ships that foundered on the sandbanks, especially near Nag’s Head and Kitty Hawk. When no ships obliged them by running aground, they lured them to their doom by tying a lantern around the neck of an old nag, which bobbing light resembled the light of an anchored ship and fooled passing vessels into thinking it a safe anchorage. When they wrecked upon the bank, these wreckers salvaged what they could and murdered the passengers.

This must have been a private horror that Aaron Burr lived with every day for the rest of his time on earth, the thought of his daughter being dragged from the hulk of the wrecked Patriot and murdered, if she were lucky before she could be defiled. And these nightmares were surely only cemented when the confessions began. In 1820, a newspaper article claimed that two pirates who had recently been hanged for their crimes admitted to having been crewmen on the Patriot, led a mutiny and killed everyone aboard. And in 1833, just a few years before Burr finally succumbed to death, another newspaper reported that a man in Mobile, AL, made a deathbed confession to his physician that he had been among the pirates who had destroyed the Patriot. According to this report, when all the men aboard had been dealt with, only Theodosia remained, proud and brave in facing her doom. As she had not resisted them, the pirates did not wish to harm her, but as it had to be done, they drew lots, and this dying pirate in Mobile had been the one chosen to take her life. Thinking it a mercy, he set a loose plank half over the edge of the vessel, and Theodosia, refusing a blindfold, walked courageously into the sea.

After Aaron Burr died, the legend continued to grow. In the last decades of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, other pirate confessions appeared. In 1874, a Texas paper published a letter by someone claiming to have been a pirate aboard the brig that took the Patriot. In his story, Theodosia attacked the captain with a bottle and was subdued. After dying during the ship’s subsequent voyage to Galveston Bay, she was buried on Galveston Island. Thereafter, yet another deathbed admission, this time by one Benjamin F. Burdick in a poorhouse in Michigan, became a prominent element of the legend. His story followed the Mobile confession closely, but this time we get a lot more dramatic details. The pirate captain wants to keep her as a concubine, but she says she would prefer to die. Giving her some time to think about her decision, she retires to her cabin and reemerges dressed in white, clutching a bible to her chest. She kneels, prays, and walks the plank, but before plunging into the icy waters, she turns, lifts the scriptures and cries out: “Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord! I will repay!” Burdick’s details supposedly match the truth well enough to credit the tale, except that he got her name wrong, calling her Odessa Burr Alston, a discrepancy that some say makes his story rather more credible. However, the bigger issue with this late addition to the legend is that it appears to confirm a version of the story told in an 1872 novel by Charles Gayarré as Burdick claimed his pirate captain was none other Dominique Youx, the pirate that took the Patriot in Gayarré’s fictional account.

Dominique Youx, pictured with the Lafittes, via Historical New Orleans.

And this version of the tale does not alone strain credulity, for others have cropped up that are equally hard to credit. One asserts that it is she who lies interred in Alexandria, VA, in a grave marked for a “female stranger” who died there in 1816 of some illness while under the watchful eye of an Englishman posing as her husband. Another claims that the pirate Dominique Youx spared her, and she was thereafter taken captive by Jean Claude Lafitte and proved instrumental in convincing the pirate to help American forces win the Battle of New Orleans. And yet another suggested she had survived the passage to Galveston Bay, kept as a sex slave by her captors but was abandoned when the pirate ship was scuttled during a hurricane. There a Karankawan Indian found her, naked and chained to the deck. He took her to wife, but she soon passed away, leaving him with a locket engraved with her name, a piece of evidence that has, of course, not been preserved for the historical record.

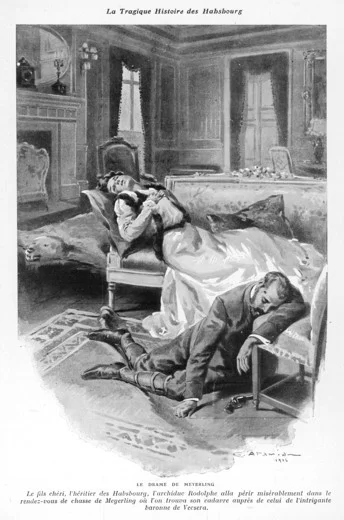

One piece of possible evidence that we do have is the so-called Nag’s Head portrait. In 1869, one Dr. Pool happened to notice a remarkable portrait in the home of a resident of Nag’s Head, NC. When he inquired about it, she explained that, many years earlier, her first husband, had been among the notorious wreckers of that coastal area and happened upon a scuttled pilot boat. Like a ghost ship, there was no one aboard, though a table was set for a meal. Believing the ship had been taken by pirates and everyone aboard forced to walk the plank, they began their salvage, and imagine their surprise when they discovered a cabin full of fine silken women’s clothing and a grand portrait. Dr. Pool, believing the portrait to be of Theodosia, began corresponding with various scions of the Burr family, and eventually, a distant cousin of Theodosia’s was interested enough to make the trip. Upon seeing the portrait, she was certain it was Theodosia because of a striking resemblance to her own sister.

The Nag's Head Portrait, via Wikimedia Commons. Compare with previous portrait.

For Aaron Burr’s part, he claimed that he never believed any of the pirate stories. “…my daughter is dead,” he insisted. “No prison on earth could keep Theodosia from me if she were alive.” But can the rest of us make claims to such certainty in this case? What do we really know beyond the fact that she was lost, plucked out of the pageant of history and hidden from the sight of the world, her fate a blind spot in the past.