Demagoguery and Know-Nothing Native Americanism

Welcome to the first installment of Historical Blindness, a blog that will explore little known passages in history. As it is intended, this blog and its associated podcast will dredge up interesting and largely forgotten stories from our past, with a specific focus on demonstrating the inscrutability, the ineffability, the unknowability of the past by examining cases of outrageous hoaxes, mass hysteria, baffling mysteries and unreliable historiography, such as apocryphal accounts that contravene accepted history, thereby raising the question, “Can we trust history as we have received it?” However, with the purpose not only of calling attention to history’s untrustworthiness but also the fallibility of our own education and memory, we shall also occasionally examine stories from our past that reflect directly upon the events of modern day with the intention of raising the question, “Have we learned nothing from received history?”

With this larger purpose in mind, I would like to first thank you, the reader, for giving this initial post a chance and next assure you that our subject matter will not always be as inherently political as you may find this first entry to be. Indeed, I originally intended to take my time developing and producing the first several blog posts so that I might build a backlog and release entries with some semblance of regularity. However, I find myself today anxious to tell a story that seems tremendously pertinent to this political moment, and to do so during this important election cycle, before we cast our ballots for President in November. It is the story of one Lewis Charles Levin, a nineteenth-century American social activist and politician whose demagoguery mirrors in many ways the rise and rhetoric of one of today’s candidates and whose life, I believe, stands as a cautionary tale not only to a public who might consider empowering such an individual, for whatever reason, but also to that selfsame modern candidate , who may wish to avoid both the tragic end of this figure as well as the ignominy that is ever the legacy of the demagogue.

First, let us look a little more closely at the term “demagogue” to clarify its meaning. Etymologically, it means little more than “a leader of people,” but in connotation and common parlance it has come to mean something more along the lines of “a rabble-rouser.” The demagogue is a disingenuous leader who says whatever will more stir the ire and passions of the populace and thereby gather the most popular support. These agitators usually foment some kind of violence among their supporters. For example, in ancient Athens, the man many believe to be the first demagogue, Cleon, inflamed the public’s prejudices against the inhabitants of the rebel city Mytilene during the Peloponnesian War to such a degree that he convinced them to vote for the execution of every single male citizen and the enslavement of the remaining citizens—a decision that was thankfully mitigated thereafter to executing only the revolt’s leaders.

G.K. Chesterton calls the demagogue “the man who says nothing and says it loud.” Perhaps most articulately and precisely, James Fenimore Cooper, in The American Democrat, describes both the demagogue’s character and methods:

The peculiar office of a demagogue is to advance his own interests, by affecting a deep devotion to the interests of the people. Sometimes the object is to indulge malignancy, unprincipled and selfish men submitting but to two governing motives, that of doing good to themselves, and that of doing harm to others…. The demagogue always puts the people before the constitution and the laws, in face of the obvious truth that the people have placed the constitution and the laws before themselves…. The demagogue is usually sly, a detractor of others, a professor of humility and disinterestedness, a great stickler for equality as respects all above him, a man who acts in corners and avoids open and manly expositions of his course, calls blackguards gentlemen, and gentlemen folks, appeals to passions and prejudices rather than to reason, and is in all respects a man of intrigue and deception, of sly cunning and management, instead of manifesting the frank, fearless qualities of the democracy he so prodigally professes.

Thus, according to Cooper, the demagogue is a leader of little sincerity who harnesses the lowest of populist sentiments—fear and hatred—in order to place himself at the head of a constituency for which he possesses no real respect or loyalty, making them promises he never intends to keep for the sole purpose of establishing himself politically. If this characterization already seems to describe well a certain modern figure on the political stage, the specific person who serves as the subject of our study will seem an actual forerunner if not a very role-model, for Lewis Charles Levin was the original mouthpiece of American xenophobia. In the 1840s, he kindled the growing fear and resentment of immigrant communities in Philadelphia, resulting in devastation for that city but political gain for himself.

Born a Jew in South Carolina, 1808, Levin seems to have searched most of his young life for a cause célèbre. He spent his peripatetic young manhood as a roving teacher studying to pass the bar. Drifting rootless through Maryland and Louisiana, marrying in Kentucky and again wandering on, he eventually found a cause to argue when in Mississippi he fought a duel and received a grievous wound. Now it is important to understand that in this era, the 1820s and ’30s, duels were fought quite frequently by gentlemen as well as the lower sort of men—it was indeed a standard resolution to quarrels and perceived slights and a common course of action when one felt the need to save face or preserve pride—but it was a practice that many in that age of reason considered barbaric and contended should be outlawed. Levin, perhaps out of some humiliation he suffered at being wounded in a duel, took pen to paper to argue against the practice. This was his first foray into political activism.

Eventually, he settled in Philadelphia, where in 1840 he passed the bar, but within two years he had abandoned the practice of the law, preferring to pursue a career as a prototypical pundit. He bought a newspaper, finding his next cause célèbre, named it the Temperance Advocate and wrote in high dudgeon against the sale and imbibing of alcohol. To Levin, the cause of temperance had extensive political implications; he associated the problem of intemperance with establishment power and fortune, asserting that the wealthy amassed their riches by offering only low wages, which in turn led to crime and vice, and that lawmakers and political parties, by licensing the sale of alcohol, were complicit in the corruption of society. In this way, Levin appealed to the prejudices of the lower classes against their employers and rulers in his crusade to banish drink from society.

Now, you may find his temperance argument sympathetic, if hyperbolic and somewhat irresponsible, but Levin’s greatest cause, which would become his raison d'être, would prove to be even more divisive and entirely sordid. Despite his familial background in Judaism, by 1843, he had embraced Christianity, perhaps because it agreed well with his campaign to correct dissolute and licentious behavior or perhaps in some earnest conversion; this we don’t know. What we do know, what the historical record does support, is that he saw something more than just personal edification and improvement in Christianity—and not just any Christianity, but specifically Protestantism, for he saw a new cause in opposing Catholicism, or more specifically, the spread of its influence in America.

*

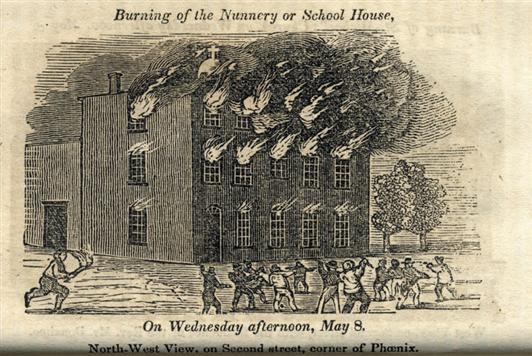

Now, Anti-Catholicism of this sort—tinged with paranoia and fear of the church’s political clout—was nothing new; it dated all the way back to the English Reformation when it was more commonly called antipapistry. And it was even on the rise during Levin’s time, in early nineteenth-century America, as Irish Catholic immigration increased. In 1834, for example, acting on rumors that women were being held against their will, an Ursuline convent was burned by Protestants in Charlestown, Massachusetts, and afterward, a former student in the convent wrote a sensational book about her time there, further inflaming the rumors. Thereafter, perhaps capitalizing on the aforementioned book’s success, one Maria Monk published a volume entitled The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, which told of forced sexual relations between nuns and priests in another convent, going so far as to allege that uncooperative sisters were chained in dungeons and the babies born of these illicit unions were murdered. Despite being later proven a libelous work of fiction, Awful Disclosures fanned the flames of anti-Catholicism and, in effect, anti-immigration as well.

In fact, Samuel Morse, better known as a developer of telegraphy and inventor of Morse Code, even ran for Mayor of New York City in 1836 on a nativist platform that was pronouncedly anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic. In letters to the New York Observer that were collected and published in 1835, Morse expressed the fear and wrath of fellow nativists in clear though hyperbolic fashion, comparing Catholicism's presence in young America to that of a snake in a crib, writing,

Let no foreign Holy Alliance presume, or congratulate itself, upon the hitherto unsuspicious and generous toleration of its secret agents in this country. America may, for a time, sleep soundly, as innocence is wont to sleep, unsuspicious of hostile attack; but if any foreign power, jealous of the increasing strength of the embryo giant, sends its serpents to lurk within his cradle, let such presumption be assured that the waking energies of the infant are not to be despised, that once having grasped his foes, he will neither be tempted from his hold by admiration of their painted and gilded covering, nor by fear of the fatal embrace of their treacherous folds.

Where Morse failed in 1836, James Harper, one of the original publishers of Awful Disclosures, succeeded in 1844, being elected the Mayor of New York City as a representative of the emergent American Republican Party. Not to be confused with the more established National Republican Party, the American Republican Party was a newly formed nativist party founded to fight the spread of Catholicism and the perceived blight of Irish immigration.

Anti-Catholic cartoon circa 1855 via the Library of Congress

Closer to Levin’s home, this militant brand of Protestantism had been stirring in Philadelphia quite a while as well. In 1831, there had been a clash in the streets when Irish Protestants paraded past an Irish Catholic church in celebration of King William’s establishment of Protestant control of Ireland in 1690. More recently, in 1842, an assemblage of Philadelphia preachers named themselves the American Protestant Association, deemed “…the system of Popery to be, in its principles and tendency, subversive of civil and religious liberty, and destructive to the spiritual welfare of men…” and resolved to “…unite for the purpose of defending [their] Protestant interests against the great exertions…to propagate that system in the United States….”

Watching this divisive movement gain support and momentum, Levin launched another newspaper, the Daily Sun, to use as a mouthpiece for his own nativist sentiment. Levin approached nativism through the lens of temperance and his steadily increasing resentment of the established political parties, the Democrats and the Whigs. As Levin saw it, candidates for office were decided on not by the people but by party insiders, in “groggeries” over “segars,” precisely the equivalent of the perennial “smoke-filled room” where cabals of secretive power brokers are said to do the dark work of true governance. Levin believed party politics to be tied up in vice and corruption and asserted that only a third party would allow for true democracy; thus he attached himself to the new American Republican Party, lately victorious in the New York mayoral election. In its Philadelphian iteration, under the auspices of Levin and other proponents, this party called itself the Native American Party. While today the term "Native American" refers to indigenous peoples, then it was a term taken up with pride to distinguish those born stateside from the wretched, tempest-tossed refuse that huddled in masses on teeming foreign shores.

While only a secretary of this nascent party, Levin was perhaps the most vocal advocate of its cause and, as a publisher, the most capable of disseminating its message. In addition to regular editorials in the Daily Sun, Levin published a book expressing his feelings on the Irish Repeal Association’s campaign to dissolve Ireland’s union with Great Britain around this time. Predictably, he did not view it as a bid for freedom, for its leader, Daniel O’Connell, was a papist who would only make Ireland beholden to the Pope. And it was just this that he warned the predominately Catholic immigrants of Europe, and particularly the Irish Catholic, intended to do in America: stage a coup by voting as a block, raising up their own men to power and subverting American democracy in favor of monarchism and deference to the Catholic Church. Our only hope, as he represented it, was to stem the surging influx of indigents and criminals and papists and to defy the cronyism and corruption of the ruling parties: in short, to support Native Americanism.

*

Before we examine the most outrageous chapter of Levin’s life, I would like to pause for a moment to offer a caveat regarding my scholarship. I make no claims to being a rigorous historian. I am a storyteller first and foremost, an entertainer; therefore, I may sometimes give short shrift to elements of my subject matter that don’t serve well the narrative I am trying to dramatize. However, my promise is that, while attempting to shape and share an engaging story, I will also make my best efforts to present the story accurately and provide reliable sources.

To that end, I should mention some other contemporary circumstances that likely contributed to the anti-immigrant sentiments of the times as well as to the general desire for a change in the status quo of party politics. All of these factors are clearly outlined in John A. Forman’s “Lewis Charles Levin: Portrait of an American Demagogue,” a comprehensive source that I have relied on heavily.

Two important dynamics beyond anti-Catholicism that exacerbated this political climate in Philadelphia were a loss of status on the national political stage and a descent into economic depression. In 1836, the most important Philadelphian in the country, Nicholas Biddle, President of the Second Bank of the United States, was stymied in his attempt to recharter the institution by President Andrew Jackson. The Bank War, as it was called, had been a prominent issue in the Presidential campaigns of 1832, and after Jackson successfully blocked the bank’s recertification in ’36, Philadelphia and her people took it as a personal defeat. No longer the central hub of the American economy, Philadelphia lost some of its eminence, and Philadelphians became disillusioned with their political leaders and open to outsider politicians that suggested the established parties were corrupt and/or ineffectual.

Then, in 1837, an economic crisis occurred that led to years of recession. In the absence of the national bank in Philadelphia, federal capital was placed in a variety of “pet banks,” relocating money from the large banks that relied on it to smaller banks that certainly benefitted from it. The practical effect, however, was panic, as major banks, now carrying far less capital, could not extend credit or offer loans as they had before. In Philadelphia, as well as elsewhere, the Panic of 1837 meant hard times, and as is almost always the case when Americans suffer economic hardship, the poor immigrant, who will often work for lower pay, is blamed for the privations of by natural-born citizens.

While the loss of their national bank and the ensuing recession certainly added to the atmosphere, one issue in particular allowed Lewis Charles Levin to really rile up his audience, and this one, again, Americans will recognize: religion in schools. The debate here, however, was not about its presence but rather about what form it would take. Catholics in the Kensington district protested that the Bible used as a reader in schools was a Protestant King James Bible and contended that Catholic students should be allowed to use a Catholic text. Levin and his Native Americans misconstrued their position, perhaps willfully misrepresenting their complaint, and warned the public that the Irish Catholics of Kensington wanted to have the Bible removed from schools, which, if it were allowed, Levin argued would lead to a new generation of idle, profligate, dissolute youth. In short, the evil immigrant papists were hell bent on undermining the very moral fabric of society.

This was the background and the political narrative when, in May of 1844, Levin’s incitements finally erupted into violence.

*

The Native Americans rallied first in Independence Square, holding forth to crowds of supporters about the Bible issue. But perhaps that wasn’t provocative enough, for next they moved their rally right into the heart if Kensington district so that the Irish Catholics themselves could hear their disparaging speeches. The first of these rallies disbanded when Irish Catholics, predictably, gathered to face their deriders. However, in the spirit of authentic agitation, Levin and the Native Americans were not discouraged from holding their rallies in the very dooryards of Irish Catholic Kensington residents but rather determined to do so again, likely hoping that violence would break out and somehow prove their dispersions against the Irish to be true.

On a stormy Monday in May, Lewis Charles Levin ascended a stage to address his audience. As if on cue, the heavens opened up with a rumble, and a downpour began—this perhaps a gesture toward divine intervention. But Levin was undeterred. Taking shelter in a nearby marketplace, he resumed his remarks, which have ever been described as passionate and incendiary.

It must have begun as a murmur at the crowd’s periphery—a confrontation between a nativist and an Irishman. Very quickly, then, it came to blows and graduated to full-scale rioting, as men brandished bricks and cudgels. When gunfire boomed in the marketplace, the first struck was a constable, shot in the face. Others received gunshot wounds in their sides, their hips, their legs. Stones and bricks filled the air, crashing down upon those gathered and battering the walls and windows of businesses and houses in the area. With the report of pistols, many dispersed, and others gave chase. Residents’ homes received barrages of rocks for no other reason than that men had fled into an adjacent alley or fallen against their doors. The damage to property was enormous, and the violence unrestrained.

The next day, the Native American convened again, no longer in Kensington, to counsel restraint. Many among their audience called for Levin, to hear what the chief instigator had to say about curbing their retaliation against the Irish rioters. Levin kept his silence, and the rioting continued for another two days. The militia had to be deployed to bring an end to it, but by then, numerous rioters on both sides as well as bystanders had been wounded, and seven were dead. When the smoke literally cleared, a seminary and two Catholic churches had been destroyed by arson, as well as some thirty private residences.

In the aftermath, Levin attempted to defend the acts of rioters, inflating the number of deaths Native Americans suffered at the hands of Irish Catholics, depicting their rally as an innocent demonstration that had done nothing to elicit the barbarities with which Irish Catholics had responded. He lashed out at rival newspapers, claiming they had incited the Catholics to lynch mobbery, and argued that the response of nativists was a natural reaction to being attacked—even the burning down of homes and churches!

Meanwhile, the rest of Philadelphia, even most of his fellow Native Americans, could not likewise defend the rioters or Levin’s increasingly outrageous rhetoric. However, public disapprobation has never been enough to sway the kind of men who do violence in the streets, and in July, the rioting resumed, this time in Southwark district, where Levin himself lived. Although the violence in this round was chiefly between nativists and the troops the governor had dispatched to keep peace, Levin characterized it differently in the Daily Sun, claiming it to be an honest struggle between native-born patriots and papist invaders. With every proclamation the governor made, Levin responded in his paper in such a way that only further incited the rioters, comparing the governor to Napoleon and claiming that his sole intent in sending the military was to revoke the people’s liberty.

Indeed, before it was over, Levin himself appears to have participated in the rioting. Levin, of course, claimed to have been present only to convince the rioters not to raze another church, but his presence among a mob during the riots—this man who had only ever encouraged their exploits—does indeed give one pause.

*

After the Philadelphia Bible Riots, Levin was running for Congress and at the same time under indictment for inciting a riot. As is often the case with a demagogue whose appeal to his supporters derives from the very fact that he encourages their prejudice, his indictment did not hurt him at the polls. He served in House of Representatives for six years, proved a belligerent firebrand in presidential politics throughout that period and was instrumental in the creation of another third party: the appropriately named Know-Nothing Party, whose platform was again strongly anti-immigration and anti-Catholicism. He became something of an annoyance to his fellow Congressmen, seem to have gone about their business dreading the times when he would monopolize the floor, holding forth on the dangers of immigration, the conspiracies of the Jesuits, and the evils of the Pope. His theories of Popish insinuations into American government—that the Catholic Church was the power behind the President!—earned him little support even if his calls for amending the naturalization process did.

By the end of his career, detractors who had always thought him somewhat unhinged were vindicated when, in an especially passionate diatribe against a Presidential candidate, he comported himself like an utter madman. In the following years, he was hospitalized for insanity. Upon his death, in a final series of indignities, the money his wife paid to procure a monument for his grave was stolen, leaving his resting place unmarked, and his family went on to convert, joining the Catholic Church he for so long had feared and despised.

*

If any part of this story rings a bell—an agitating politician, an appeal to prejudice, encouragement of violence for political ends—then think carefully about the parallels and choose sensibly in the ballot box this November.

I thank you for reading the first installment of Historical Blindness. Again, as this blog is just starting out, and I am no veteran blogger, I beg your patience as I work on establishing a consistent schedule. As I explained, I wanted to get this post, which you might consider a preview or a pilot, out to you before the election. If you enjoyed this first installment, please subscribe using the RSS feed linked at the bottom of the page, and in the future, poke around more in this website to dig further into each upcoming story and find other products, such as links to my forthcoming novel, Manuscript Found! At the bottom of the page, you’ll find links to follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram as well, where I promise we'll soon be more active. And if you feel moved to support this endeavor and make it possible for us to release installments of the blog and podcast more frequently, you’ll also find a button there that links to our Patreon page, where you can donate and hopefully in the future earn rewards. Keep an eye out for our next installment, which is already in the planning!