The Turin Shroud: Divine Likeness or Bogus Relic?

On the third day of the 1898 public exhibition of the Shroud of Turin, Secondo Pia was in his darkroom, developing the plates of the first photographs of the sacred object. The king himself had asked Pia, an amateur photographer and the mayor of a small town, to come and capture an image of the shroud during this commemoration of the Italian constitution’s signing. He had set up bright arc lights to illuminate the object, an ivory-colored linen 3.5 feet wide and 14.5 feet long with symmetrical patterns where it had been burned and water-stained while folded, like a Rorschach inkblot, and he had dutifully photographed it while clergymen looked suspiciously on, worried that somehow he would damage the fragile fabric. Now, in the red light of his darkroom, as he bathed the photo-sensitive printing plate of his photograph in developing solution and the image began to appear, he found himself shocked and elated, for there on the negative was a clear image of a man captured in the cloth.

Now, the image of a man was actually something he expected to see, something he had already seen with his naked eye, for the Shroud of Turin had long been venerated as the burial shroud of Christ because of that very image—a bearded, long-haired man, naked, his arms crossed in front of him, with what appeared to be dark bloodstains corresponding to the wounds of Christ. The history of the shroud and its veneration could be traced all the way back to Lirey, France, where in 1453 Margaret deCharny, who had been exhibiting it as a great relic that had come into her family’s possession, traded it to the House of Savoy in exchange for a castle. Thereafter, the cult of its veneration established itself in a chapel at Chambéry before it was transferred among several Italian and French cities for decades, exhibited occasionally around Easter. In 1532, a fire in the chapel at Chambéry damaged the shroud, which was doused with water to extinguish the flames, leaving the marks visible on it even today. Nuns made some repairs by patching sections, and after that, the shroud settled in Turin, where it had remained for most of its years, exhibited less and less frequently, until its 1898 exhibition.

What Secondo Pia discovered that year in photographing it, therefore, was not that the image was present in the cloth, but rather that, in his negative, it was far more distinct, with greater detail than any had previously imagined. The reason for this was that his negative showed the image as a positive, which meant the image in the cloth was itself a negative, something that thinkers of that era, and even those today, struggled to explain. At first, Pia and his development process came under scrutiny, with many suggesting that he had altered or touched up his photo, something he vehemently denied.

The image in the shroud (left), itself a negative, and a negative of the image (right), itself a positive, via Wikimedia Commons

With the discovery and the controversy, of course, came fame, and soon the whole world—including skeptics, agnostics, atheists, and scientists—were looking very closely at the shroud. One of these, an anatomist and zoologist faculty member of the Sorbonne, Yves Delage, encouraged a young staffer at his biology magazine to investigate the shroud. This staffer, a Catholic biologist and painter named Paul Vignon, threw himself into the work, closely examining the Pia negative and searching for some natural explanation of the image. What he found convinced many, including his boss, Delage, that this truly was the burial shroud of the historical Christ.

The image revealed in the negative depicted with far more exactitude wounds that agreed almost perfectly with biblical accounts of the crucifixion. The man showed wounds that might indicate being nailed to a cross, and though the feet were only visible on the second image, which offered a back view of the corpse, it could be seen that the feet were crossed as though they had been nailed together. Moreover, the expanded and raised rib cage, as well as other aspects of the anatomy, indicate a struggle to breathe because of arms being raised, and the blood stains from the hand wounds appear to have flowed from wrist to elbow, which can only be explained if the hands had been raised while bleeding and then afterward been forced down to their crossed position—which itself would have damaged the body once rigor mortis set it, and some have pointed to what seems to be a dislocation of one shoulder for confirmation of this. But the correspondence does not cease there. In Pia’s image, clear marks from lashes can be seen, as well as injuries on the back and shoulders as from carrying a large and heavy beam and on the knees from having fallen, all conforming to the story of his forced march to Golgotha carrying his cross, even down to the detail that the lash marks on his back appear less distinct than those on his front, indicating a garment had been thrown over his shoulders before he carried his burden and agreeing again with the details of the Bible. Then there was the swelling of his cheeks, which fit with the detail of his being struck in the face, and of course, the wound in his side. Really the only details that didn’t perfectly match were that the wounds, presumably from nails, were in his wrists rather than his palms, which at the time was where most believed Christ had been pierced, and the lacerations on his head as from thorns were not simply around his brow, but over his entire scalp, as though a whole hat of thorns had been employed. But these are details that others would eventually confirm as being even more historically accurate than a forger might have known, for a nail in the wrist, in what has come to be known as Destot’s Space between the tendons, would actually have been necessary to support the weight of those crucified, and a “crown” of thorns, in that region and era, would likely have been more of a full-headed cap than a wreath.

Detail of the hands and forearms showing the wound in Destot's Space and the direction of the blood flow, via The Epistle

Regardless of the anatomical and historical accuracy of the wounds, though, Vignon wanted to find some explanation for how the image had been made, especially in its seemingly miraculous form as the negative of an image that would not be revealed in all its particulars until the development of photography. First, he ruled out paint, as that would have cracked and flaked off the often rolled and folded shroud long ago. Next, he ruled out a dye-job as dyes could not have produced the effect of a negative image and would appear the same whether as a negative or a positive. Therefore, it must have been formed by pressing the cloth directly to a body, a process he then tried to reproduce with a chalk impression. While this did produce a negative image, that image was distorted from the linen being pressed around a three-dimensional face; therefore this process was ruled out as well. Only one technique appeared to hold up in the end: that of a vaporograph, wherein the rising of vapors and a chemical reaction created a negative impression in the cloth. According to Vignon’s final theory, which bore out under experimentation, the shroud had been spread with a balm of aloes and myrrh mixed in olive oil, which became oxidized and stained the cloth brown when the body’s sweat, rich in urea after its torturous ordeal, fermented into an ammoniac vapor. A complicated explanation, but one that could be in some ways reproduced and at the very least did not rely on notions of holy radiance. Nevertheless, some hints at miraculous goings-on remained, for the body could not have long stayed in the shroud without its putrefaction staining the fabric, of which stains there were no signs. Furthermore, Vignon could not account for how the blood stains, which seemed so perfectly formed, had not been disturbed when the shroud had been removed. Did these remaining mysteries hint at resurrection?

Regardless of these persisting questions, Vignon’s employer, Delage, was so taken by the research that he presented it at the French Academy to much approval. However, the atheist secretary of the Academy worked against the theory for seemingly personal reasons, refusing a vote of confidence and censoring the paper to remove mention of Christ. Then a French priest and historian known for discrediting relics weighed in with a discovery of his own. He traced the shroud to its furthest historical appearance to debunk it. The shroud had first appeared in Lirey, France, in 1354 at the castle of a knight of the Crusades, one Geoffrey deCharny—forefather of the Margaret deCharny who would eventually sell it to the Savoys. This relic-debunking priest had come across a document from 1389, the D’Arcis Memorandum, in which a Bishop D’Arcis, upset about the Crusader knight’s son displaying the object as Christ’s burial shroud, claimed he had previously investigated it and “discovered the fraud and how the said cloth had been cunningly painted, the truth being attested by the artist who had painted it, to wit, that it was a work of human skill and not miraculously wrought or bestowed….” After this bombshell, for the veracity of which there was no further evidence, not even the name of the supposed forger, the Shroud of Turin was buried, as it were, in disrepute and obscurity.

The D'Arcis Memorandum, via the Turin Shroud Encyclopedia

In the 1930s it was exhibited again, and again it was photographed. This time, the pictures were taken by a professional photographer, though still with the darkroom help of Secondo Pia, who is said to have exclaimed, “It’s the same!” when the image appeared. This time, with advances in photography being what they were, the image was even clearer, and to avoid similar accusations of chicanery, they invited numerous professional photographers to examine their plates and attest that they’d not been retouched.

Thus one doubt was finally laid to rest, but then so was the shroud, and with the second world war and the dubious inquiries of Nazis to have access to the shroud, it became necessary to bury it even further. The shroud was spirited away to a Benedictine monastery south of Rome, where it was hidden beneath the altar and, if worse came to worst, the monks could secret it away in a cave.

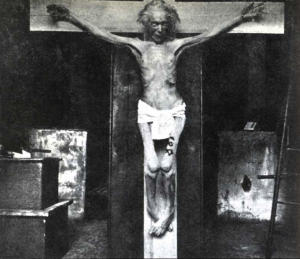

Eventually, it would be brought home to Turin, but during its long absence, it remained at the forefront of many people’s minds. Through these decades, researchers into the shroud remained actively investigating, now using the new and better photographs, which included close-ups of specific portions of the shroud. The study of the relic became a scholarly field unto itself, with a noun coined: sindonology, from the Greek sindon, meaning linen or linen covering. These sindonologists came from almost every field of research and ranged from staunch believers to cynical doubters and every position in between. In 1950, these seekers held the first of many congresses, international conferences at which all kinds of new theories might be put forward and old theories revisited and revised. To give an idea of the kind of work a sindonologist might perform, consider Dr. Pierre Barbet, who, intrigued by the anatomical accuracy discernible in the new photos of the shroud, used his access to cadavers to experiment with crucifixion and its effects. It was Barbet who discovered, during the course of his many morbid experiments, literally crucifying corpses in his laboratory, that driving nails through the Destot’s Space, between the tendons at the wrist, was not only feasible as a means of suspending men on the cross, but was actually necessary to support their weight as victims remained up there, pulling themselves upward by those nails in order to breathe. Moreover, he discovered that driving a nail into that place caused the thumb to draw inward, which just so happened to be another detail of the image on the shroud.

A cadaver crucified by Dr. Barbet, via Mad Scientist Blog

One major project of sindonologists has always been to put together a more complete history of the shroud, for if its passage through time could be confirmed all the way back to Christ, then there would be little more to argue about. The problem was that no history existed before its appearance in France in the 1350s, and even then there existed a variety of cloths venerated as the burial shrouds of Jesus. Sindonologists made a striking connection when they began to notice that many famous depictions of Christ appeared to match the face in the shroud, such that it seemed many were copies of it. Tracing these similar icons led Paul Vignon, the original sindonologist, to a very early supposed image of Christ called the Mandylion, or the Image of Edessa, as it had been discovered in Edessa, in Mesopotamia, in 544 CE. The image, supposed in legend to have been given to a king Abgar V by Jesus himself, was only of Christ’s face. As the legend went, a gravely ill King Abgar sent for the miracle-worker Jesus, and Jesus, instead of coming in person, wiped his face on a cloth, leaving a miraculous image, and sent that to Abgar, a gift that healed him. The Mandylion, a Greek word for veil or cloth, ended up in Constantinople by 944 CE, where it was revered until Crusaders sacked the city in 1204. Now sindonologists have pored over ancient manuscripts listing the city’s treasures and contemporary descriptions of the Mandylion itself to suggest that, in fact, it was the shroud that would eventually turn up in Lirey. They point to some accounts that call it a shroud, and others that indicate it might have had an image of Christ’s entire body, not just his face, and still others that point out it had been “doubled in four,” which if one were to do to the Shroud of Turin, one would end up with just the image of the face on top. Critics of this theory point out, however, that in many of these documents, a shroud of Christ is mentioned as a separate treasure from the Mandylion.

And there remains the question of where this Mandylion or shroud had been in the hundred and fifty years between the sack of Constantinople and its appearance in France. The explanation, for some sindonologists, was the Knights Templar, present at the taking of Constantinople and known for hoarding treasures and relics. Indeed, one of the last Templars burned at the stake was one Geoffrey deCharnay, a name close enough to deCharny that it seems reasonable to assume he was a progenitor of the family that formerly owned the shroud. And some have even suggested that the idol the Templars were accused of worshiping, an image sometimes described as a bearded man and called Baphomet, which I discussed at some length in episode 13, was actually the shroud of Christ. But this is all conjecture, of course. Further scientific advancements in the study of the shroud would not arrive until that wonderful decade, the 1980s.

Abgar receiving the Mandylion, via WIkimedia Commons

In the 1970s, a secret commission formed to advise the church on matters of preserving the shroud and allowing for scientific testing. Under their auspices, scientists have had further access to the shroud, including samples for study. From one such sample, pollens specific to certain regions were extracted that proved the shroud had been exposed to air in Palestine, Turkey, and Europe, which veritably traces the path from Christ’s burial, to Constantinople, to France. In 1982, a group of scientists formed STURP, the Shroud of Turin Research Project, and using microscopy and computer image analysis, they confirmed that the dark marks on the shroud were indeed human blood.

Then the moment of truth: Carbon-14 dating. The test had long been proposed, but whether the church was concerned about damaging the shroud or revealing it as inauthentic, it had always been denied. In 1988, however, a small portion of the shroud from its bottom left corner, away from the image itself, was divided among scientists at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Oxford University, and the University of Arizona. With 95% certainty, each lab independently confirmed the age of the cloth to be between 728-608 years, which placed its origins squarely in the Middle Ages, between 1260 and 1380 CE. This effectively shut down the entire debate, making of the shroud a medieval forgery. Time magazine said it had been debunked. The New York Times called it a fraud. And one might think this to be the end of the Turin Shroud…but sindonologists are a resilient and ingenious bunch. That same year, they began to cast doubt on the Radio Carbon dating, protesting that the fire it had survived in the 1500s must have altered its carbon content, not to mention the fact of the likely chemical reactions that had originally taken place in the cloth to form the image. And besides, scientific analysis had proven that the image contained three-dimensional data, which had been modeled on computers, and therefore could not have been made by even the most talented of artists. What did that leave then? The idea that some medieval ascetic had reenacted the passion, including coincidentally historically accurate details they didn’t have at the time, such as the position of the nails in the wrist, and followed burial practices that inadvertently resulted in the vapography of the image? Or perhaps the sample that had been dated was itself suspect. One sindolonogist went so far as to claim, without evidence, that a secret carbon testing had been performed on an adjacent sample that had been dated to much earlier…so…obviously they had to test it again.

This undermining of the Carbon-14 results has continued to modern day, with accusations that the piece tested had actually been a patch added in the Middle Ages. Of course, there had been patches, after the fire, but those were clearly visible. These had been imperceptible, critics of the carbon dating claimed, because of a technique called “invisible reweaving.” Interestingly, one proponent of this theory published a paper in which he claimed to have tested the remnants of the sample used for carbon testing and had detected dye in it, proving the patch had been disguised to match the rest of the shroud. As noted skeptic Joe Nickell pointed out, it was odd to point to the presence of dyes as proof the shroud is authentic, since that proposition relies in large part on the cloth not containing pigments added by man, but regardless, the claims appeared to be wholly false, since the samples tested by the three laboratories in 1988 had been entirely destroyed in the dating process. And Nickell’s criticisms have since been proven sound in a publication of the same journal that had printed the spurious claims. Moreover, as for the notion of pigments having been added, testing has indeed revealed that iron oxide, an ingredient in ancient paints, is present on the cloth. However, sindonologists protest that these particles may actually be blood that has broken off and been spread around the cloth, or that, if it is indeed paint, then there has been cross-contamination from the paintings hung in the many cathedrals where the shroud has been exhibited over the years.

Even just last year, we had yet further developments, on both sides of the argument. First, although it has been proven that human blood is present in the dark stains, it has now also been proven that reddish pigments have been added, as though to touch up those stains, indicating that some form of artistry has been wrought upon the shroud. Then a development that seems more in favor of the notion that the Turin Shroud is the true shroud of Christ, or at least that it’s not a painting, came when a study claimed that the iron particles, rather than indicating paint, actually derive from the blood of an individual who endured great trauma.

So what are we to come away with? What are we to think? To say that it’s shrouded in mystery would be a bad pun and something of a cliché. But it is true. Here we see very clearly the age-old struggle between rationalism and faith writ large. What you see when you look at the Turin Shroud may depend entirely, in the end, on what you see when you close your eyes and think on the greatest mystery of life.