The Lost Colony and the Dare Stones, Part Two

Front and back of the original Dare Stone, via Brenau University

Welcome to Historical Blindness, the Odd Past Podcast. In this installment, we will continue our exploration of The Lost Colony of Roanoke with an examination of what may be the most outrageous archaeological find, or hoax, of the last century. If you did not read the previous installment, please do so before continuing to this, part two of The Lost Colony and the Dare Stones.

In 1937, nearly 350 years after John White’s discovery of the colony’s disappearance, the story of the Lost Colony jumped suddenly back into the national consciousness with the discovery of a remarkable artifact. This item, a rock, was brought to Emory University of Atlanta by one Louis E. Hammond, a man purporting to be a tourist from California. This stone, which carried a mysterious engraved message, immediately captured the interest of History Professor Haywood Pearce, for this stone’s inscription appeared to be a message from none other than Eleanor Dare. On its face, beneath a cross (significantly a Latin cross, with one arm longer than the other, rather than the Maltese cross, with arms of equal length, which had been the agreed upon signal to indicate the colony had gone inland), was carved the message “Ananias Dare & Virginia went hence vnto heaven 1591 Any Englishman Shew J·hn White G·vr Via.” On the reverse side of this stone, which you can view above, a longer message was carved in Elizabethan English, this one harder to make out for its Middle English orthography and the fact that both a’s and o’s seem to appear as rough-hewn dots: “Father s··ne After Y·v g·e f·r Engl·nde we c·m hither ·nlie mis·rie & W·rre T·w yeere Ab·ve h·lfe De·De ere T·w yeere m·re fr·m sickenes beine f·vre & Twentie s·lv·ge with mes·ge ·f shipp vnto vs sm·l sp·ce ·f time they ·ffrite of revenge r·nn ·l ·w·ye wee bleeve yt n·tt y·v s··ne ·fter ye s·lv·ges f·ine spirts ·ngrie suddi·ne mvrther ·l s·ve se·ven mine childe ·n·ni·s t· sl·ine wth mvch mis·rie bvrie ·l neere fovre myles e·ste this river vpp·n sm·l hil names writ ·l ther ·n r·cke pvtt this ther ·ls·e s·lv·ge shew this vnto y·v & hither wee pr·mise y·v to give gre·te plentie presents.” This message was signed “E W D,” presumably for Eleanor White Dare.

The stone told a clear enough story. Soon after White left them, the colonists came “hither,” presumably to the place the stone had been found, suffered misery and war for two years, losing more than half their number to illness within another two years. We are given the number 24, though it seems unclear whether that represents the number who expired or survived. It sounds as if it is the number dead, but this would not be “above half” the number left behind, so Pearce read it as the number who survived. Thereafter, a “savage,” or Native American, reported to the surviving colonists that a ship approached, and this caused some fear of revenge that drove the natives to flee, even though the colonists apparently did not believe the ship to belong to their countrymen. Afterward, supposedly driven by angry spirits or simply in an angry mood, the natives massacred the remaining colonists, leaving only seven alive. Eleanor reports that her child and husband were among those slain, whom they buried around four miles east of “this river”—presumably meaning the river near which the stone had been discovered—on a hill where they’d left another stone, this one a grave marker inscribed with the names of the dead. The message ends by explaining that this stone had been given to a native to give to White (or as the reverse side indicates, to give it unto any Englishman, who would then show it to White) on the promise that the native messenger would be rewarded with gifts upon delivering it—a problematic detail to which we shall return.

The find, if genuine, was a monumental discovery, but Pearce and his colleagues, wary of hoaxes, examined it and questioned its discoverer, Louis E. Hammond, closely. Hammond was a tourist out of California. By one report a seller of produce, Hammond claimed to have stopped along a newly built causeway in swamplands along the Chowan River in North Carolina to hunt for hickory nuts. These swamps had for many years been inaccessible, and even rumored to be a pirate haunt in days of yore; thus, when Hammond tripped over the 21-pound piece of quartz and saw its inscription, he thought perhaps it represented a clue to the resting place of buried treasure and took it with him. Two months later, he arrived at Emory University in Atlanta, seeking a translator. Pearce and his colleagues saw no evidence of fraud in the stone, noting that its inscription might have been made with tools available to colonists and that its message appeared consistent, idiomatically and orthographically, with Elizabethan English. Therefore, they followed this mysterious Hammond to the place where he claimed to have found the stone.

Hammond took them to the causeway and whipped out a crude map scrawled on a paper bag, but to their chagrin, November rains made it impossible for him to pinpoint the site where he had pulled it from the ground. Frustrated in his search, Hammond led them to a sand bar; there an old sunken barge marked the place where he had supposedly washed the stone—and not only washed it but scrubbed it with a wire brush and accentuated the lettering using a pencil! These misguided efforts of Hammond’s were later blamed for the inability to properly assess how long the stone had lain in the swamp.

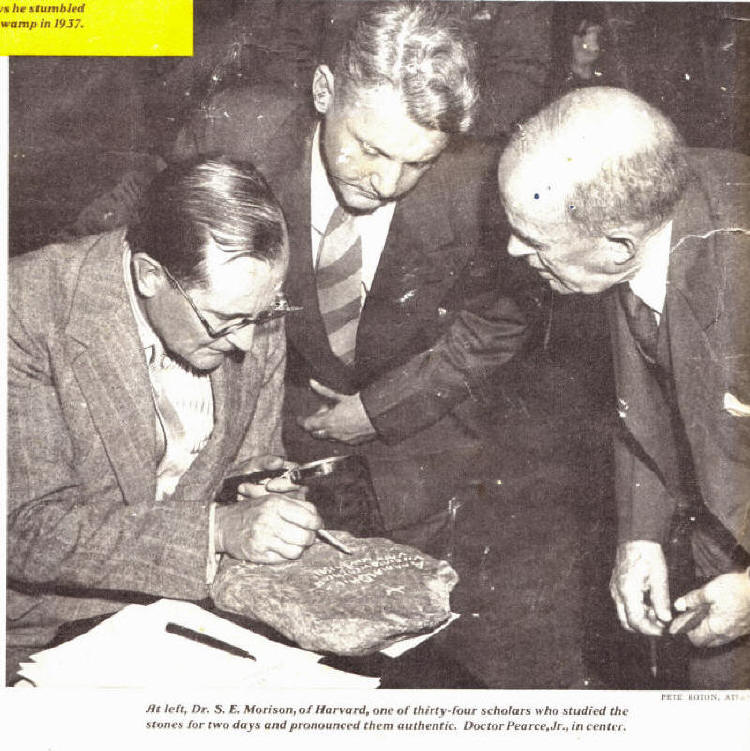

Dr. Haywood Pearce, examining stone with colleagues, via Brenau University

Pearce remained skeptical, but feeling that the stone warranted further investigation, he hoped to find the grave marker alluded to in its inscription as a verification of its authenticity. There is, however, at least to my understanding, an error in logic here. The stone referred to a grave “east this river,” as if the Dare Stone was meant to remain in one location, presumably there on the western side of the Chowan, and act as a guide to the grave marker on the hill. But then it says “put this there also,” which wouldn’t make sense with the previous statement, and then “savage show this unto you,” indicating the stone had been given to a native as a message to be given over to any Englishman. This appears wholly nonsensical. If it were meant to stay by the river and point any who came across it to the other side of the river and the grave, then it would defeat the purpose to place this stone also at the grave or to instruct natives to carry it away from that spot to an Englishman in exchange for gifts…

None of these inconsistencies appear to have occurred to Pearce, though, as he seems to have been far too excited over the prospect of finding the grave to consider such contradictions. Unfortunately, though, as he was embarking on his quest for the gravesite, rumors had already begun to swirl that he had actually already discovered Virginia Dare’s grave. In an effort to quash these reports, he published a translation of the stone in January of the next year. Thereafter, the former mayor of Edenton, a town near the purported discovery site of the stone, wrote Pearce with a tantalizing anecdote. As a young man, he had performed logging work in the swamps east of the Chowan, just where the Dare Stone claimed the grave marker could be found, and incredibly, he recalled a remarkable moss-covered stone upon a hilltop that might have been the very marker Pearce sought. Of course, Pearce set out to find this rock, and on finding it, very carefully removed the moss to find…nothing at all. Therefore, he began to excavate the hill, certain that he would find the resting place of the dead colonists, and in the process, he turned up…no indication of remains whatsoever.

Regardless of this dig’s failure, Pearce was undeterred, and since his first media promotion of the investigation had resulted in a promising lead, he might be forgiven for thinking that further advertisement of his search might provide a real breakthrough. In hindsight, however, he surely regretted his subsequent decision to offer a $500 reward for any who could find or lead them to the grave marker in question.

The story takes a careening turn then when William Eberhardt, an uneducated stoneworker, almost a year and a half after the arrival of the Dare Stone at Emory, approached Dr. Haywood Pearce with another find, this one purportedly found some 300 miles from the first, south and west and one state over, in South Carolina. The stone Eberhardt showed Pearce was inscribed with a much different style of script that at first blush seemed unreadable, although a date, 1589, could be discerned. Pearce dismissed it as a Spanish gravestone, telling Eberhardt they would keep the stone and translate it, but that the reward they had offered was only for a stone that would be found near the Chowan River in North Carolina. Eberhardt, undaunted, returned with two more stones bearing the same date and supposedly found in the same region. One might imagine this trying Pearce’s patience, as he explained to Eberhardt again that the stone he sought would not be found in South Carolina. Moreover, Pearce apparently explained to Eberhardt exactly what the date on the stone he sought would be, and therefore one might imagine that he very well could have shared some further details as to what would mark the Dare gravestone he wanted so desperately to find. Amazingly, then—or perhaps predictably—Eberhardt returned with exactly the stone Pearce pursued.

The aforementioned Eberhardt stone on display at Brenau University, via The Virginian-Pilot

The stone Eberhardt brought him bore the following legend: “Heyr laeth Ananias & Virginia Father Salvage mvrther Al save seaven names written heyr mai God hab mercye Eleanor Dare 1591.” On the reverse surface were inscribed 15 names, which in combination with Ananias and Virginia Dare was exactly the number of dead Pearce expected to be memorialized on the grave marker. A triumph of luck and archeology, it seemed. But what about the fact that Eberhardt still claimed to have found it so far from the first stone? Rationalization can scale any mountain, it seems, for Pearce simply changed his theory to accommodate, apparently reasoning that the first stone had been carried by its Indian bearer from South Carolina all the way to North Carolina in search of the promised Englishmen who would trade great gifts for it—never mind the “east this river” bit.

Eberhardt certainly had Pearce’s attention then. Upon interrogation, Eberhardt revealed his lack of education, which made him more trustworthy in Pearce’s eyes, and explained that, by pure chance while travelling, he had discovered a site with multiple engraved stones resting in a gully at the base of a hill. He had taken only one with him as a curio and had returned to recover others when Pearce had been uninterested in the first. Indeed, he claimed to have discovered thirteen more stones there, and he produced all of them for Pearce. Of course, Pearce asked to be shown this site, and Eberhardt obliged, leading him into a rural area near the Saluda River and showing him a depression in the ground where he said the stones had lain when he discovered them.

What remained was to test the authenticity of the stones, and to test the veracity of Eberhardt. The stones passed scrutiny, although whether or not that scrutiny might have been cursory or deficient is hard to surmise at this historical distance. Pearce and the experts he consulted found Eberhardt’s stones to bear what appeared to be authentically Elizabethan language. Moreover, their inscriptions, in most of their particulars, such as the names mentioned, appeared to correspond with extant accounts from John White and John Smith. And finally, chemical tests to examine oxidation and weathering seemed to indicate that the stones were old (although how old could not then be determined) and, more importantly, that the cut surface within the engraved letters appeared to be equally weathered. Further convincing was Pearce’s investigation of Eberhardt’s background, which confirmed his lack of education and therefore the likelihood of his inability to accurately approximate Elizabethan English and his lack of familiarity with relevant historical records that corroborated the names inscribed on the stones.

Eberhardt and Pearce on the Chattahoochee River, from the Saturday Evening Post, via Angelfire.com

The final indication to Pearce that Eberhardt was on the level came when the man passed a tricky test. Trying to catch Eberhardt out, Pearce suggested that, rather than accepting the promised $500 reward, Eberhardt take only $100 and a 50% stake in the property on which he had found all the stones, a piece of land that, if the stones proved authentic, would surely be worth far more in time. Eberhardt’s decision to take the stake in the property seemed to confirm to Pearce that Eberhardt himself believed the stones to be genuine. He therefore made the deal, feeling more confident in the discovery, and subsequently sent Eberhardt out to find further stones in the South Carolina area and into Georgia. Since the stone with the colonists’ names had a further message along the edge that read, “Father wee goe sw,” or southwest—which to me seems a clear effort by a forger to explain why the Eberhardt stones had been found hundreds of miles southwest of where Pearce expected to find them—Pearce hoped more stones would be found to the southwest of Eberhardt’s hill. The next stone to be found, however, was not turned up by Eberhardt but by a resident of Atlanta named I.A. Turner who claimed to have found the stone along the Chattahoochee southwest of the hill while hunting, contacting Pearce because of an Atlanta newspaper piece on the other stones. Turner’s stone matched all of Eberhardt’s in its script. Signed again by Eleanor, it appeared to indicate that more stones would be found by the same river. And sure enough, Eberhardt thereafter discovered nine more stones along the Chattahoochee. And in the next year, as dozens of new stones were lugged in by various different people for scrutiny, the last vestiges of Pearce’s skepticism were finally obliterated when an assemblage of Georgian farmers reported that they had seen such stones, inscribed with what they had always believed were the writings of Native Americans, up to fifty years earlier. One farmer, T.R. Jett, who had lived throughout his childhood in the area where these latest stones had been discovered, claimed to have seen two such stones in his youth, one of which had been displayed in his family’s mill and widely remarked upon. While he could not recall what had become of those stones, the aforementioned I.A. Turner (the first to find a stone in Georgia besides Eberhardt), another local, claimed to recall where the stone had been discarded after its exhibition in the mill and, fantastically, managed after so many years to find it for Pearce. The second stone from Jett’s memory had apparently been hauled out of the river and split into two pieces, one of which had reportedly been used as part of a stone construction in a barn that no longer stood. Surely this fragmented stone could no longer be found… but no, with a little encouragement, Jett managed to find one half in a ditch and the other in an old tool chest. The pieces fitted together perfectly, and one might imagine this moment like a pivotal scene from a historical mystery thriller, when the music swells and the outlandish theory is proven factual.

In all, 48 Dare Stones were discovered after the first, and 42 of them by Eberhardt! Always the stones were picked up with no witnesses around to confirm their discovery, but sometimes Eberhardt was able to show indentations in the ground that fit his finds. The inscribed story beyond the first stone was predictable at first and then, before its conclusion, sensational. The stones indicated that some so-called “savages” had shown the colonists much mercy, whereas others, from the east, had massacred them. Talk of burying the dead was common. All the while, some effort was made to look for Governor White’s return (a dubious claim considering how far inland these stones had supposedly been found). Thereafter, talk of a native king taking the surviving colonists in and taking Eleanor to wife, seemed to take the narrative in a decidedly romantic direction. This narrative was not unfolded to Pearce in any linear fashion, as stones were found out of the chronological order of the story they had to tell, but eventually, all was pieced together. If the stones were to be believed, Eleanor Dare, after losing her husband and daughter to murder, married a native chieftain, lived with him, possibly in a cave, in “primeval splendor,” and eventually bore her new husband a child, another daughter whom, according to one stone, she named Agnes and whom, according to another, she hoped her father would find take back to England. Eventually, some conflict arose among the natives owing to the birth of the girl, but before that could be further explicated, the narrative resolved with an ominous remark upon Eleanor’s sudden illness. This story in stones concluded with a date of 1599, when it might be presumed that Eleanor expired from some naturally arising ailment, although it might also be speculated that she was poisoned by those of the tribe who were upset over the birth of her daughter.

Cover of the Saturday Evening Post issue in which Sparkes's article appeared, via Angelfire.com

Regardless of any conjecture this story might inspire, however, all theories arising from it were soon proven moot, for consensus regarding the authenticity of the Dare Stones was about to shift rather dramatically. After further study and corroboration by visiting professors hailing from institutions as storied as Harvard, Pearce wrote to the Saturday Evening Post regarding the stones, and the Post sent journalist Boyden Sparkes down to Georgia to look into the matter. According to the article that Sparkes eventually published in the spring of 1941, which has been quite useful in composing my own account of the affair, Sparkes immediately found Pearce wary and even hostile—specifically when Sparkes suggested that it stretched the imagination to believe a Native American might have been prevailed upon to lug a 21-pound stone around on the off-chance he might be able to exchange it for goods sometime in the unforeseeable future.

Sparkes inquired about the university at Chapel Hill’s lack of interest in the stones, and Pearce suggested that Paul Green, faculty at Chapel Hill and author of a popular play about the Lost Colony, was angry because filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille, who had been sniffing around Green for source material, had now turned his attentions to Pearce. Sparkes very sharply pointed out that Hollywood’s optioning of historical source material had become a big business, especially there in Georgia after the success of Gone With the Wind, and suggested that this entire affair of the Dare Stones may have been a scheme to draw Hollywood’s attention, even going so far as suggesting that Hammond, the mysterious Californian, might have been a hoaxer on some Hollywood production company’s payroll. Indeed, it seemed that someone had tried to sell a stone at Manteo, where Green’s play was put on, long before Hammond ever showed up at Emory. According to Sparkes’s article, a local senator remembered some huckster who came through the area promoting a real estate project and a coastal highway and had outright suggested the creation of bogus relics using old ballast stones. Among the other schemes this out-of-towner had brainstormed were carving CROATOAN on a log and sinking it out where fishermen would pull it up in their nets or claiming to find one of Governor White’s buried chests. According to Sparkes, who says he tracked down records of this mysterious man kept by the administrators of that coastal highway, this stranger had even been caught filming Paul Green’s play with a handheld camera on opening night and been asked to cease and desist. But perhaps most discrediting is that Sparkes claims Pearce knew about this suspicious story yet still gave weight to Hammond and his stone.

A 1939 production of Paul Green's "The Lost Colony," via TheLostColony.org

Sparkes further debunks the notion that various unaffiliated farmers independently corroborated the existence of the stones found in Georgia. According to his article, Eberhardt was close friends with all the other finders of the Georgia stones, and the Jett family, who purported to remember the stones in their mill, was also acquainted with Eberhardt through his companions. In fact, while Pearce averred that Mr. Jett easily identified the stone from memory, Sparkes’s interview with Mr. Jett suggests that the man actually made the identification under rather strange circumstances and with no small amount of coaching. It seems Jett had shot his landlord with a shotgun, and it was while being held in jail that he was approached by Pearce and shown the stone through the bars of his cell. Jett did not identify it immediately, as Pearce indicated, but did so after getting out of jail, and Sparkes implies that Pearce may have helped him in some wise. Jett’s remembrances are further made dubious by his claims that he never could read the “Indian writing” on the stones in his youth, whereas the stones he identified are clearly inscribed with English lettering! Sparkes’s working theory was that the Jett stones were purposely inscribed with g’s carved to resemble the figure eights mentioned in some witness accounts of old stone relics that probably did at some point exist.

Moreover, Sparkes went himself to examine the tool chest in which Mrs. Jett reportedly found half a stone that fit perfectly with the other half a stone that had supposedly been part of an unmortared pillar. He makes a convincing case that any stones banging around among tools in a chest and surviving the ruin of a building would be chipped and not fit together, as he puts it, as neatly as a “freshly broken teacup.” Although there does appear to be corroboration for stones with “Indian writing” being stored in that tool chest, he suggests that, in pursuit of the reward money offered, Mrs. Jett could easily have replaced the remembered stones for one manufactured by Eberhardt and his cronies.

Sparkes not only cast doubt on Hammond and Eberhardt, but he also pointed out ways in which Pearce had essentially invited fraud and swindlery by offering monetary incentives and, even more damning, that he had seemingly exaggerated or misrepresented the details of his own investigations into the stones’ authenticity. To wit: one of the other finders of stones in Georgia, known friend of Eberhardt I. A. Turner, had apparently been promised some pay by Pearce and told Sparkes he planned to sue Pearce over the matter. Turner insinuated that, if the stones were hoaxes, Pearce knew all about it.

Sparkes also indicates that Pearce’s investigation of Eberhardt’s background actually turned up some suspect past behavior, such as the fact that he had actually sold bogus Indian relics to an antique dealer in the past! Pearce allegedly left this bit out of his writings to the Post, and when Sparkes finally met up with Eberhardt himself, finding the man in a shack, sick and intoxicated, he learned of another detail Pearce had glossed over. The way Pearce told it, the fact that Eberhardt had taken an interest in the hill where his stones were discovered rather than the full $500 reward proved he was on the level. However, in 1940, Eberhardt had sold his share of the hill back to Brenau University for $1400, which along with other remuneration for stone-hunting amounted to far more than the original reward. It would seem Eberhardt was a savvier businessman than Pearce represented him to be. Moreover, while Pearce had characterized the hill as uncultivated, Sparkes reports that a local farmer grew cotton on it and, when shown photos of the stones, asserted he’d never seen them there before.

And as perhaps the most ridiculous aspect of Eberhardt’s story, Sparkes points out the overwhelming coincidence that only Eberhardt had found stones even when other, more learned men were searching the same areas, and that by the end, Eberhardt was finding them conveniently quite near his own home!

Pearce and Harvard scholars examining Dare Stone, from the Saturday Evening Post, via Angelfire.com

Turning his attention back to discrediting Pearce himself, Sparkes dug through reports on scientific testing and found that Pearce had even ignored some findings by his own experts, who had pointed out that letters had been carved to purposely avoid disturbing lichen and some even appeared to have been carved as recently as a few days or weeks earlier! Moreover, Pearce appeared to have purposely misrepresented expert evaluations of the stones to say they could not be reproduced through short-cut methods, when in fact it seems any stone-cutter might have accomplished the same engraving using a variety of modern methods. Furthermore, Pearce’s claims that the language on the stone was altogether consistent with Elizabethan English conveniently ignored the exceptions made by linguists that a few words, including “primeval,” appeared wholly anachronistic.

Perhaps most damning was Sparkes’s uncovering of Pearce’s correspondence with the film director Cecil B. DeMille, which indicated that he did indeed seek to sell his new history to the filmmaker in the form of the rights to a different play from Green’s, one he had co-written himself based on the story related by the Eberhardt stones.

After Sparkes’s Saturday Evening Post article, titled “Writ on Rocke,” was published, Bill Eberhardt contacted Pearce’s mother, wife of Brenau University’s president, and requested a meeting, which she agreed to, thinking Eberhardt wanted to show her a new stone. And lo and behold, he did have a new stone to show her, but this one was inscribed with a threat. “Pearce and Dare Historical Hoaxes,” it read. “We Dare Anything.” Eberhardt informed Mrs. Pearce that he would release the stone to the Post as proof of forgery unless the Pearces gave him $200. Pearce received this message from his mother, and whether or not the fact that Eberhardt had indeed forged his stones came as a shock to him, it undoubtedly was received with despondency, for the jig was up. Pearce went to confront Eberhardt with a witness, and Eberhardt reportedly received them with a rifle laid casually and menacingly across his lap, bidding Pearce to keep his distance. Pearce demanded something in writing before he would surrender the money, but Eberhardt would sign nothing incriminating. Afterward, with only the corroboration of his witness to validate his claim, Pearce went to the press and made the front page of the Atlanta Journal on May 15, 1941, with the headline, “Hoax Claimed By ‘Dare Stones’ Finder in Extortion Scheme, Dr. Pearce Charges.”

The effect of the Post and Journal articles was to turn the Dare Stones into a nationwide laughingstock and destroy Pearce’s academic reputation and career. Although Eberhardt denied Pearce’s allegations, saying that he’d never forged any stones but rather found them where Pearce had told him to look, the matter of the Dare Stones was laid to rest in the court of public opinion. For the next 70 years, the Dare Stones were all dismissed as hoaxes.

However, recent interest in the original Dare Stone, the one presented to Pearce at Emory by Hammond, has once again cast doubt on accepted history and weakened these certainties for some. These doubts were raised by, of all things, a History channel docudrama released in 2015. The program follows a couple of stonemasons, the Vieira brothers, who are best known for a previous History channel special attempting to prove the existence of an extinct race of giants, a conspiracy theory previously covered by one of the Vieiras in a TED Talk that was subsequently removed by its Youtube curator as pseudoscience. In their special on the Dare Stones, they investigate on behalf of the Lost Colony Center for Science and Research, a rather sensationalist society that pursues a variety of theories in regard to the colony’s fate, some more outlandish than others, such as that the colonists relocated as part of a secret operation to harvest sassafras, a crop valued as a curative for such ailments as syphilis. The film goes into detail telling the story and has the brothers examining the stones. Of course, they find that Eberhardt’s stones were likely engraved using a drill press, while the first stone’s lettering is, they suggest, more consistent with chisel work. More interesting, though, is the claim of one Dr. Kevin Quarmby, presented as an expert linguist in the program (and indeed his credentials seem appropriately impressive although his background appears to be more in the area of Shakespeare and Early Modern Drama rather than linguistics, per se) that the word “ye” with a superscripted e, which has long been taken as a second-person personal pronoun (as in “you”), is actually representative of the written form of the definite article “the,” which would seem to indicate either authenticity or a counterfeit of such genius that the forger was actually better versed in Elizabethan writing than the Harvard professors who evaluated his work. This assertion has led Brenau University, which remains the keeper of the stones, to call for renewed academic examination of the first Dare Stone, which in turn necessitates a closer study of its purported discoverer, the enigmatic Louis E. Hammond.

Hammond—who claimed to have been traveling with his wife when he discovered the stone, though no one ever saw her—turned out to be something of a phantom. Due to their immediate suspicions of a hoax, Pearce and his associates at Emory had tried to tail him one night but were eluded. On another occasion, they tried to collect his fingerprints from a glass, but to no avail. Pearce even claimed to have hired Pinkerton detectives to investigate his background, and no evidence of the man’s existence was ever turned up. Likewise, the Vieira brothers of the History channel special hired their own investigator to track down proof of a Louis E. Hammond’s existence in California at that time. Tantalizingly, the investigator found proof of a Louis Hammond who served time in Folsom Prison around that time for forgery, but the age of this prisoner seems to be different from that of the Hammond who brought in the stone, according to descriptions, so the connection remains indefinite.

The Vieira Brothers, looking here for all the world like serious researchers, via New York Daily News

It appeared that at least in one regard Hammond told the truth, for the fact that he hailed from California seems to have been confirmed. After leaving Georgia for home, Hammond wrote from somewhere in Alameda, California—with a P.O. Box return address—suggesting that Pearce and Emory University charge 25 cents to view the stones. To Emory University administrators, this proved Hammond to be a fraud, so Pearce had thereafter been obliged to take the stone to Brenau University, where his father was president and various other family members served as administrators and faculty—a move that would further discredit him to Boyden Sparkes. It did appear, however, that Hammond just wanted some cash for his find, and after managing to obtain a weak reference from some jewelry store owner that confirmed little more than that, indeed, Louis Hammond existed, Pearce and Brenau University gave Hammond some money for the stone, and Hammond thereafter vanished.

But was it possible that Louis Hammond was in league with known forger Bill Eberhardt? One account suggests at least that this was not so. According to Boyden Sparkes, it appears that Hammond stuck around long enough to be aware of the Eberhardt stones, and Eberhardt’s co-conspirator Turner claimed to have been approached by Hammond and asked to find a stone with the word “Yahoo” on it. This apparently was an attempt to prove that Eberhardt and his friends would turn up a stone with any word asked for, thus demonstrating their stones to be hoaxes. However, Turner and Eberhardt did not take this bait, and Pearce, unfortunately, took this as further proof that Eberhardt was in earnest. So, I suppose it is still possible that Hammond and Eberhardt’s crew were working together to convince Pearce of the stones’ legitimacy, but such an elaborate con strains credulity.

Nevertheless, the questions remain. Was the first Dare Stone a fraud, as the ensuing stones turned out to be? Was Hammond that same huckster known to be planning similar pranks around the Manteo area during the premiere of Green’s play? Or was he perhaps a Hollywood henchman dispatched to drum up a marketable narrative for a future blockbuster?

If the first stone is genuine, then consider the implication of the inscription that it was both left as a marker pointing to a grave site AND as a message to be carried by natives to Englishmen who would reward them with gifts. Where is the logic in its message? Or even regardless of the confusing content of its inscription, if there is any doubt as to its authenticity, shouldn’t modern science be able to settle the matter one way or another? Until that time, this will remain a lapse in the clarity of history, a beshadowed corner of our historiography, an episode of historical blindness.

Detailed image of front of original Dare Stone, via The Wall Street Journal

Thanks for reading Historical Blindness! This installment was researched and written by me, Nathaniel Lloyd. If you enjoyed this post and would like to read more thought-provoking stories from our shared past, please listen to the podcast and spread the word by subscribing and leaving us a positive review on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher and by sharing the program with any friends you think might enjoy it. Explore this website to find previous installments and other products, such as a link to my forthcoming novel, Manuscript Found! At the bottom of the page, you’ll find links to stay up-to-date with our latest installments, products and recommendations by subscribing to our RSS feed or following us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. If you feel moved to support our program and make it possible for us to release installments more frequently, you can follow the navigation link at the top of the page to www.historicalblindness.com/donate, where you can contribute a one-time donation or pledge recurring support through Patreon. All donations contribute directly to the composition and production of the program, and with enough support, a more frequent release schedule would be more feasible. Keep an eye out for our next installment, and thanks again for reading!