The Found Manuscript of Wilfrid Voynich

A page of the Voynich Manuscript, via Wikimedia Commons

In this installment, The Found Manuscript of Wilfrid Voynich, we blow the dust off an ancient tome, crack its brittle spine and open it to find… mystery.

There is something transcendent in discovery. It is a feeling unparalleled in its exhilaration, felt by a detective uncovering a clue or an archaeologist brushing soil off a momentous find. There is, though, some difference to be discerned here between a snoop discovering a telltale receipt in a pile of trash and a scholar lifting an intact and glittering artifact from earth in which it has lain unseen for ages. Discoveries of a historical nature tend to quicken the pulse perhaps more than others, for they have been overlooked or hidden for so long that their discoverer feels an even greater excitement and pride in bringing them to light.

Having experienced this to some degree, I can myself attest to the elation, after interminable hours in a quiet library staring at glowing yellow microfiche as it slides and blurs past, of finally glimpsing something that looks like it might be useful, reversing the spool and discovering just the old newspaper column I was seeking, just the piece of proof I needed. While my experience may pale in comparison to the real thing, I like to believe I can imagine what it is like to make a significant historical or literary discovery, to find a lost manuscript or a previously unknown document of tremendous academic worth. It would be akin to finding buried treasure.

The “found manuscript” has long been a trope in fiction, especially in stories with a Gothic sensibility. Consider Edgar Allen Poe’s short story, “Manuscript Found in a Bottle” as a handy example. The idea that the reader holds a true account of some terrible events, penned by the very protagonist of the story, has proven compelling ever since; one must only look to the modern popularity of “found footage” horror films for confirmation. As a result, one might be tempted to dismiss such framing of tales as a flourish of melodrama. Sometimes, though, life imitates art, and tropes such as these find their way into reality. Take, for example, Anne Frank’s diary, found and kept hidden by those who gave Frank’s family refuge.

Recent famous examples of found manuscripts have tended to be lost novels of famed artists rather than personal narratives of unknown individuals like Diary of a Young Girl. In 2004, the daughter of Ukrainian Jew and Parisian novelist Irene Nemirovsky discovered two novels from an unfinished series her mother had called Suite Française. The novels had been written in a miniscule script and had to be read using a magnifying glass. Nemirovsky’s daughter had long ago put the papers containing the novels in a drawer, for reading through her mother’s writings, most of which were personal, had been heartbreaking, as Nemirovsky had been murdered along with her husband at Auschwitz. Suite Française, upon its posthumous publication, was hailed as a masterpiece.

A young Walt Whitman, via The New York Times

Even just this year, in February, a found manuscript made headlines, this one discovered by a grad student at the University of Texas and originating from the great American poet, Walt Whitman. The discovery of this novel, which apparently Whitman disavowed entirely before shifting into the most prolific and masterful stage of his career as a writer, can be imagined much as I described the lonely scholar in the library. The grad student who found the book, Zachary Turpin, made his discovery only after years of poring over newspaper archives and digitized papers. Turpin describes his discovery as a slow and arduous process that culminated in the opening of a PDF and the uttering of some “unprincipled words.” Whitman’s novel, Life and Adventures of Jack Engle: An Autobiography, has been described as a rollicking city mystery in the tradition of Charles Dickens and has been made available in full for your reading pleasure by Walt Whitman Quarterly Review.

These stories of tragedy captured for the ages and literature snatched out of the jaws of obscurity for induction into the canon are touching and lovely to be sure, but what of the Gothic? What of the dark and mysterious tomes? What of the Necronomicon, bound in leather of dubious origin and clasped with cold, pitted iron? What of the anonymous grimoires found on disused shelves, the apocryphal scrolls hidden at the back of Dead Sea caves?

Of these, there is but one found manuscript that can be rightly considered the most mysterious book ever discovered: the Voynich Manuscript.

Round about 1911 or 1912, a London dealer of antiquarian books named Wilfrid Voynich came into possession of a most unusual manuscript. According to his own accounts of the acquisition, he discovered the manuscript in a southern European castle, in a chest where it had been hidden long ago, unbeknownst to its custodians. It caught his attention as an illuminated manuscript, meaning a handwritten document decorated with marginalia and brightly inked illustrations, which indicated great age and perhaps significant worth. Compared to the other manuscripts in the chests, Voynich called it an “ugly duckling,” small, nondescript… but further analysis showed it to be far more intriguing than the cover let on, for this book’s illustrations and style of script were unlike any other he had seen before. The content of this manuscript, indeed, was enciphered, and its illustrations mystifying.

The plain cover of Voynich's "ugly duckling" manuscript, via Wikimedia Commons

Some conflicting accounts of the manuscript’s discovery have since arisen, suggesting that the manuscript was part of a collection owned by the Roman Catholic Church and kept by the Jesuits at Villa Mondragone in Frascati, Italy, and that the sale was made knowingly to Voynich as someone who knew how to keep a secret, presumably from the Vatican. This, however, does not necessarily change what seems to be the most important part of the story to me: that the keepers of the manuscript did not realize the significance of the document they held. So perhaps Voynich did still “discover” the manuscript in riffling through the contents of a chest and recognizing its unusual character, whether or not he found the chests or was invited to look through them.

One can better understand why the Jesuits considered Voynich to be a book dealer “whose discretion could be trusted” when one considers his checkered past. He was no stranger to adventure and intrigue and resisting authority. Born a Polish noble and educated as a chemist and pharmacist in Moscow, somewhere along the way he became radicalized and began to follow the anarchist Sergius Stepniak. In Warsaw, he conspired in the escape of fellow radicals from the Warsaw Citadel, a plot that was foiled, landing Voynich himself in the Citadel. After escaping himself, although not without contracting consumption and acquiring a perpetual hunch in his posture, he persisted in his anarchist activism and eventually found himself sentenced to labor in a Siberian salt mine. Managing to escape again, he journeyed westward, to Hamburg, where he sold the clothes off his back for passage to England, arriving in 1890 with little else besides a scrap of paper with the address of Sergius Stepniak, who had taken up residence there in exile. Among other political exiles, Voynich was involved in printing and distributing propaganda literature and remained active in politics until Stepniak’s untimely death, when he went into antiquarian book dealing. Yet even as a book dealer, he was known to show his battle scars and point out which had been the work of swords and which of firearms.

Voynich plying his trade, via Voynich.nu

A frequent visitor to monasteries and convents across Europe, Voynich was something of a fast talker and slippery character, talking credulous monks and nuns out of their valuable old collections in exchange for worthless modern texts.

Even previous to finding his cipher manuscript in Frascanti, Voynich had become known for including “Unknown, Lost or Undescribed books” in his catalogues, and he did a tidy business with the British Museum. Among the documents he sold to the museum, at least one was determined to be a forgery after his death. Despite the fact that as a dealer, the forgery had likely fooled his as well, rather than being perpetrated by him, this has led some to suggest that the cipher manuscript later known as the Voynich Manuscript may have been a hoax cooked up to earn him a tidy profit. However, the fact is that, after discovering the manuscript, Voynich made no attempt to sell it but rather exhibited it. Some years after finding it, in fact, he became obsessed with studying the book and for the rest of his life developed theories regarding its provenance, authorship and purpose. Such was the draw of this unusual manuscript that it became the prized possession of the dyed-in-wool wheeler-dealer Wilfrid Voynich.

So what made the manuscript so interesting? The illustrations were odd, certainly, but not as odd as some other illuminated medieval manuscripts, which depicted anthropomorphized animals committing various atrocities, a variety of cryptids and demons and even some archaic pornography to boot. The most commonly cited of these is the Smithfield Decretals, which the Voynich Manuscript doesn’t come close to in terms of bizarre illustrations. So it must have been the script in which the book was written that first drew Voynich’s interest, for upon closer examination, it was impossible to discern whether it was written in a cipher or in some unrecognizable language.

A mitred fox preacher ministers to flock both literal and figurative, from the Smithfield Decretals, circa 1300-1340, via Wikimedia Commons

The Voynich Manuscript is divided into distinct sections. These have been identified by scholars such as René Zandbergen, whose extensive work on the topic has been an indispensable resource for this episode, as herbal, astronomical/astrological, cosmological, biological and pharmaceutical in content, as well as a section with only text and stars drawn in the margins. These delineations, however, have been discerned based solely on the artwork, as the strange language or code in which the book is written has never been deciphered. The least mystifying are the astronomical and cosmological passages, which depict in circular and spiral diagrams the sun, moon and certain recognizable constellations, illustrations of zodiac degrees similar to those called paranatellonta, and a variety of geometrical diagrams. The biological illustrations prove odder, portraying naked women in baths and waterslides. The figures are sometimes called nymphs, or water spirits, and the sections sometimes alternatively labeled balneological, in reference to the depicted hydrotherapy. Lending more mystery to this sections are the theories that the baths and pipes through which these nymphs frolic actually represent internal human organs or that they might be a demonstration of alchemical processes.

A page from the "biological" section of the Voynich Manuscript, via Wikimedia Commons

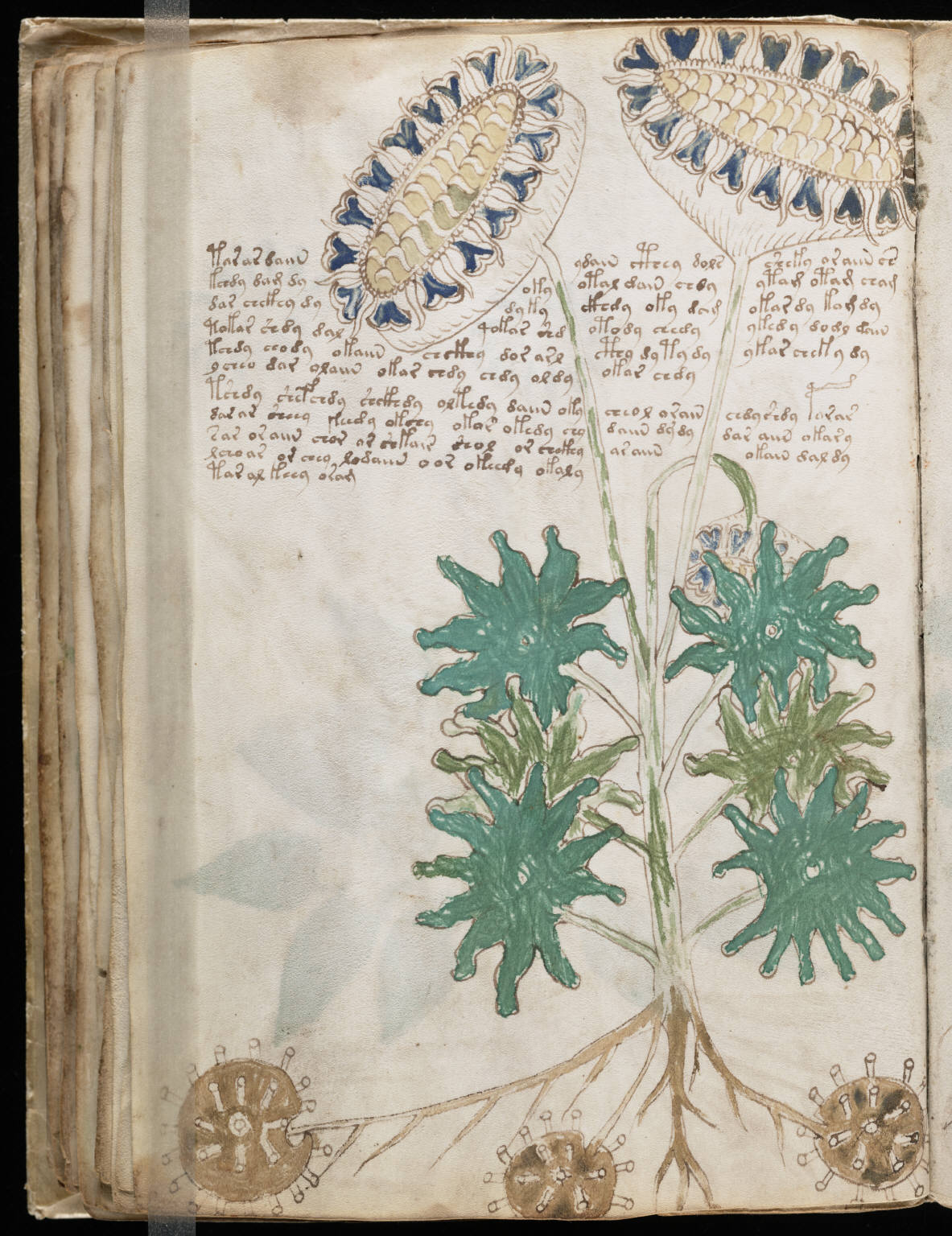

The majority of the manuscript is comprised of herbal illustrations showing entire plants in detail, from root to stem. The remarkable thing about these illustrations, though, which has fueled many of the wilder theories regarding the manuscript, is that the plants cannot be recognized as species that exist in nature! This has led, of course, to suggestions of otherworldly provenance and further cemented the Voynich Manuscript’s place in legend. Meanwhile, the more staid assessments of skeptical historians raise the valid points that some other well-known alchemical treatises also carry illustrations of entirely fantastical plants, and that herbal illustrations from antiquity were often hand copied from one manuscript to another, resulting in some abstraction and corruption as depictions became further and further caricatured and unrecognizable.

A page from the "herbal" section of the Voynich Manuscript, via Wikimedia Commons

Nevertheless, it was surely the unusual character of the illustrations and the secrecy implicit in the text’s encipherment that piqued Voynich’s interest and led to his years of scrutiny and theorizing. And he had a stroke of luck in discerning some of the manuscript’s early history in the form of a letter found inside the manuscript from one Johannes Marcus Marci, a scientist of Prague, which establishes that the book was gifted to Jesuits in Rome in 1665. In the letter, Marci indicates that the manuscript once belonged to Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II. This letter and the clues contained therein provided the basis for Voynich’s theories regarding its authorship and early history prior to showing up in Prague in the 1600s. Marci indicates that “[t]he former owner of this book…devoted unflagging toil [to its deciphering]…and he relinquished hope only with his life.” The letter further revealed that, when it arrived to the court of Rudolph II, “…he presented the bearer who brought him the book 600 ducats. He believed the author was Roger Bacon, the Englishman.” Thus one of the longest lasting theories of the manuscript’s origins was perpetuated.

Voynich made a presentation of what he called the Roger Bacon manuscript at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 1921, promoting his belief that the manuscript had been authored and encoded in the latter half of the 13th century by one of the fathers of experimental science, Roger Bacon, a theory that has persisted among some fringes even after radiocarbon testing dated it to the 15th century, taking on more and more outlandish character, such as that in the manuscript Bacon describes galaxies he viewed through an anachronistic telescope or that Bacon was preserving secret knowledge of alien technology.

Based on the letter, Voynich appears to have taken it as a given that Roger Bacon was behind the manuscript, and perhaps more interesting is his theory of who owned the manuscript prior to Rudolph II. Voynich came to the conclusion that the “former owner” referred to in Marci’s letter was none other than John Dee. If you are not familiar with Dee, he was a notorious English polymath, an advisor to Queen Elizabeth, and an all-around fascinating individual deserving perhaps of his very own episode—and indeed I may return to him in the future. Suffice to say here that in addition to his knowledge of mathematics and astronomy, his reputation as an occultist and magician was unparalleled. Indeed, he may be responsible for our modern image of wizards as long-bearded, robe-wearing crystal ball wielders with funny hats.

"John Dee performing an experiment before Queen Elizabeth I," Oil painting by Henry Gillard Glindoni, via Wikimedia Commons

The theory of Dee’s ownership of the manuscript maintains traction even today, where on Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library’s webpage for the manuscript, Dee is still included as part of its history. Actually, there is plenty of support for this theory. John Dee did indeed present himself at the court of Rudolph II. He and his dubious cohort Edward Kelley, on a mission they believed had been assigned to them by an angel of God with whom they had made contact through invocation magic, went to the Holy Roman Emperor to tell him he was possessed by demonic forces and to recruit him in their efforts to establish a unified world religion through direct communication with God and His angels.

Their journey proved fruitless, but regardless of their failure in this endeavor, some surviving accounts from John Dee’s son note that, while in Bohemia, Dee held in his possession “a booke...containing nothing butt Hieroglyphicks, which booke his father bestowed much time upon: but I could not heare that hee could make it out.” It is also shown in Dee’s own journal, in October of 1586, that he had 630 ducats, a sum comparable to the price the Marci letter states was paid for the cipher manuscript.

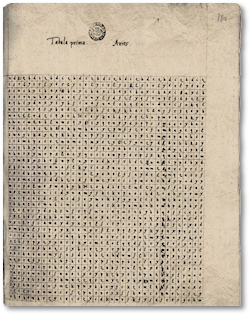

However, these pieces of evidence have not stood up under scrutiny, for John Dee was known to have had another cipher manuscript in his possession at the time: The Book of Soyga. Indeed, it was this manuscript that so vexed Dee in its impenetrability, such that when Edward Kelley first claimed to have made contact with an angel, one of Dee’s first questions was whether or not the book held anything of value and whether the angel could help him read it. The Book of Soyga remained a legendary grimoire, known only by reputation and from the few allusions made in Dee’s writings, until, in another astounding discovery of a lost manuscript, historian Deborah Harkness stumbled upon the book catalogued under an alternate title in the British Library in 1994. It is now deciphered, translated and available for the public to read online, a treatise on astrology and magic and thus by its very nature mystical, to be sure, though now no longer a complete mystery.

A cipher table from the Book of Soyga, via Mariano Tomatis's Blog of Wonders

The existence of the Book of Soyga certainly casts doubt on Voynich’s assertion that his cipher manuscript was the one in Dee’s possession in Bohemia, but perhaps more suspect is the fact that Voynich appears to have based his theory of Dee’s having owned the manuscript entirely on a 1904 work of embellished historical fiction by Henry Carrington Bolton masquerading as a scholarly work entitled The Follies of Science at the Court of Rudolph II.

Even today, the theories of the Voynich Manuscript’s origins and contents remain contested. Among them persists the idea that it is a hoax. Certainly the dating of the manuscript to the 1400s did much to assuage the notion that Voynich himself forged the book, but nevertheless doubt remained, mostly suggesting that the indecipherable language must not really be a language or code at all, but rather a kind of artful gibberish, for surely a real language would have been translated, a real cipher decrypted after so much time and analysis. One theory in this vein that I find entertaining is the idea that it is not a real book at all but rather a prop created by Francis Bacon for a stage production, thus making the “code” in which it’s written a simple mock language meant only to fool audiences from afar, with illustrations that needed only be convincing at a distance.

This idea of the manuscript as a work of art puts one in mind of another mysterious book with bizarre artwork and indecipherable text. In 1981, artist Luigi Serafini published his Codex Serafinianus, which also featured illustrations of imaginary plants and captions in an unreadable script. The difference here, however, is that the artist forthrightly admits the language to be wholly invented and meaningless, and the artwork goes far beyond depictions of herbs, with strange machinery and creatures, often showing things fused together in troubling and fantastical ways, like the famous image of a couple that transforms into a crocodile while performing coitus. Serafini admits to having worked on the Codex while under the influence of the hallucinogen mescaline, and he says his intention was to instill the feeling of bemusement that children experience when looking at books they cannot comprehend.

A page from the Codex Serafinianus, via Wired

While the notion that the Voynich manuscript is nothing more than a work of art intended to mystify is certainly pleasing, especially since, if that were its purpose, it has accomplished it remarkably, the fact is that recent scholarship suggests the book may be decipherable after all. In 2013, a study approached the problem of deciphering the text using information theory and concluded that the text indeed contains linguistic patterns, indicating there is some meaning to be found in its pages. And the following year, University of Bedfordshire linguistics professor Stephen Bax claimed to have finally deciphered words in the text, including names of plants in the herbal sections—juniper and coriander—and the name of a constellation in the astronomical section: Taurus.

If these advancements in the study of the manuscript are to be taken as signs of progress to come, then we may eventually know the content of the book. Nevertheless, even then, its origins may remain forever shrouded in mystery, lost among competing theories, such as that it was written by the heretical gnostic Cathars of Southern Europe, that it was an Aztec medical text, or that it was penned by Leonardo Da Vinci using his non-dominant hand.

Indeed, one has the impression that mystery will surround Wilfrid Voynich’s found manuscript no matter what we learn about it. And perhaps some books are destined to remain unread, some chapters of the past meant to remain blank. Still, one does hope that, with enough time and study, our historical blindness might be cured, at least in this regard, enough to bring the manuscript’s words into focus.

*

Thank you for reading Historical Blindness. If you enjoy these explorations into the blind spots of history, you may be interested in an exciting new project I'm launching.

Tying in with this installment’s theme of found manuscripts, I am publishing one of my own. After long years of research and composition and revision, I am finally publishing my debut historical novel. The book makes use of the found manuscript trope I discussed earlier, and at its center is a very famous story of a supposedly found manuscript, for the novel explores the beginning of Mormonism from a skeptical perspective. In fact, the novel’s title is Manuscript Found!, the first in a trilogy. The following is the dust jacket synopsis:

In early nineteenth-century Western New York, a world of mobs and secret societies where belief in visions and magic is still commonplace, two men compose manuscripts that will leave indelible marks on society, and one woman finds among the religious and political turmoil a pretext to exert an influence outside her appointed sphere. In this debut novel exploring the beginnings of Mormonism and the rise of America's first third-party political movement in opposition to Freemasonry, Nathaniel Lloyd delineates the intersections of religion and politics and the power of secrets and falsehoods. The first volume of a trilogy, Manuscript Found! establishes compelling characters and follows as they become embroiled in the political and religious affairs of their age, unaware that fate will eventually bring them together on the western frontier.

You can find links to the book here on the website; go check it out if you’re a reader!