The Beautiful Corpse of Helen Jewett

The New York City police force did not come to be until 1844, after a surge in population and poverty resulted in a significant increase in vice and crime. Before that, the city had employed a corps of 80 civilian patrolmen, the Nightwatch, who stood sentry on street corners every evening. One early Sunday morning in April, 1836, two of these watchmen, Dennis Brink and George Noble, had the final few quiet hours of their shift in lower Manhattan shattered by a sudden alarm being raised from a nearby brothel on Thomas Street. “Fire!” cried a woman from its doorway, prompting Brink and Noble to investigate. The woman, one Rosina Townsend, madam of the establishment, led the watchmen to the room of one resident, a prostitute named Helen Jewett, who was found murdered in her bed, three deep and bloody wounds on her head, and her bedclothes still smoldering from a fire that had presumably been set to conceal the crime. Brink and Noble questioned the madam and the other ladies in residence at the brothel. They discovered that the last visitor Helen Jewett had seen was a young regular of Jewett’s who went by the name Frank Rivers at the brothel. The madam indicated that she had seen Rivers in Jewett’s room late Saturday evening and did not believe he had left, and that shortly before discovering the fire in Jewett’s room, she had been awakened when someone left the house by its back door. Investigating the yard, the watchmen discovered a hatchet, and in an adjacent yard, they found a discarded cloak with a fringe that witnesses insisted belonged to the young man Frank Rivers. After some further investigation, the watchmen learned that Rivers’s real name was Richard Robinson, the 19-year-old son of a landed Connecticut state legislator. Robinson had been living in a boardinghouse and clerking for a local mercantile establishment. When it was suggested that the hatchet the watchmen had discovered belonged to the store where Robinson clerked, the watchmen determined to track down their young suspect and haul him back to the scene of the crime. The watchmen found Robinson still asleep; Robinson’s roommate, James Tew, answered and confirmed that he and Robinson had visited the brothel the night before, though Tew had departed earlier than his roommate. Rousing Robinson from his sleep, the watchmen accompanied the young men back to the Thomas Street brothel and confronted them with the crime. In their estimation, Richard Robinson was all too composed when receiving the news, denying his guilt in the murder but also not appearing surprised or upset. As was the custom at the time, a coroner’s jury was convened, composed of numerous random people who who happened to be present to weigh the facts as they were known and determine on the spot whether anyone should be accused. The jury declared that the deceased had come to her end by the hand of Richard Robinson, and the youth was immediately taken to jail to await a trial that would turn out to be one of the most notorious and sensational in American history.

In my last post, I mentioned in passing that James Gordon Bennett, the enterprising editor of the New York Herald penny paper, made something of a name for himself with his sensational coverage of the infamous Robinson-Jewett murder trial, actually pioneering the printing of extra editions in his zeal to publish more and more material about this scandalous crime. While this crime might not be so well known today, it was the most notorious criminal case of its time, perhaps only rivaled by the trial of Levi Weeks for the murder of Elma Sands, which I focused an episode on some years ago. In my discussion of Levi Weeks’s murder trial, I presented the notion of that trial and the many popular narrative accounts of its court proceedings representing the dawn of the popular true crime genre in America. If that is so, then this case, less than 40 years later, which was even more heavily written and read about, not just in published court records as in the Weeks trial but also in the cheap penny papers that were then becoming more and more popular, represents the full realization of the public’s thirst for salacious tales of sex and murder. This case has been written about in much detail in intersectional studies of gender and class in early 19th century America, and it has been picked apart as a seminal moment in the history of American journalism. But in these academic analyses, the tragic narratives of the victim and the accused and the newspaperman for whom the case became an obsession tend to get lost. Therefore, in retelling this legendary historical true crime tale, I hope to better emphasize the real human stories at its center as I further explore the mystery of this unsolved crime. And at the core of this mystery is a forgotten woman, remembered to posterity by an alias, which newspapers at the time didn’t even print correctly. The Helen Jewett of public imagination was the creation of an infatuated newspaperman, a fictional character constructed more to sell newspapers than to provide any real insight into the life taken that spring night.

James Gordon Bennett, editor of the New York Herald, who turned the Helen Jewett murder into a sensational press phenomenon. Public Domain image.

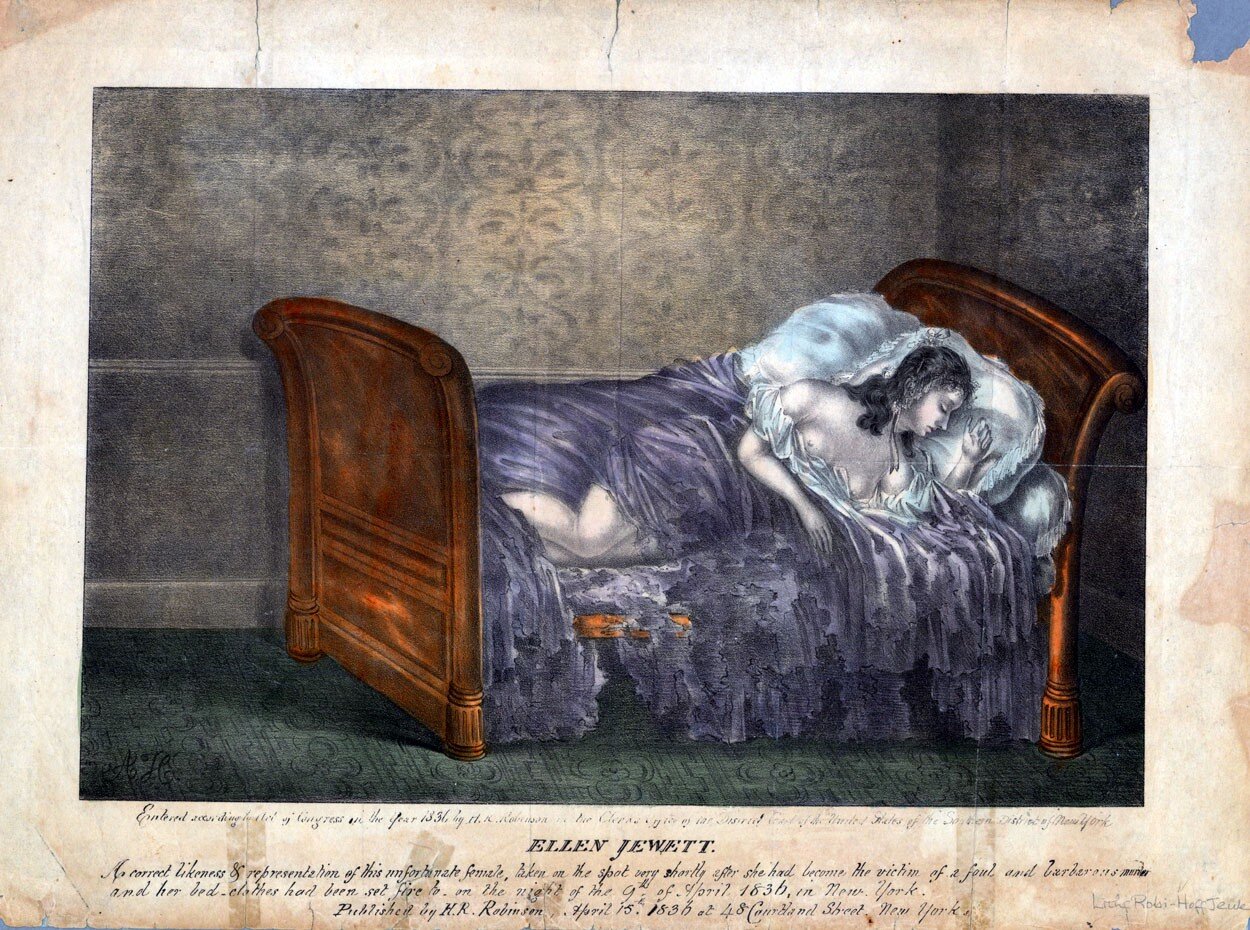

The sensational news coverage of the Helen Jewett murder began the very next morning, when James Gordon Bennett, the editor of the penny paper the New York Herald gained entrance to Jewett’s room and viewed her body. With him was an artist who would create lithographs of the scene for his newspaper, but the first-person account Bennett afterward wrote and published describing what he saw in her room gave a rather more vivid impression than could any illustration. It should be said that Bennett was something of an odd character, rather a joke to many in New York City. He had formerly been the editor of a partisan newspaper but had broken away to start a penny paper because he chafed under the editorial constraints of political subsidization and wanted independence. However, in order to break into the penny paper field, he found he could not focus on the kind of credible banking and political news on which he wanted to report, for the readers of the new penny papers wanted reports on robberies and murders. Nevertheless, he tried to have it both ways, reporting on crime as well as on Wall Street and printing political attacks on the editors of rival newspapers. These takedown pieces, criticizing the political affiliations and views of competitors, led to a series of physical assaults, when newspaper editors he had criticized actually beat him with their canes in the middle of Wall Street. It got to the point that one rival penny paper declared Bennett to be “[c]ommon flogging property.” It was at this low point in his career and life that Bennett entered Helen Jewett’s room and seemed to see in her some reflection of himself. He saw her expensive clothing and jewelry, so out of place in her brothel room, and he understood she was a high-priced prostitute who made a successful living. He saw that she was literate, with editions of several periodicals and volumes of Sir Walter Scott and Lord Byron on her shelves, and even a portrait of Byron upon her wall. To Bennett, she may have seemed like someone who was struggling for upward mobility in the rigid class structure of New York, much like himself, and also like him, she had been struck down for her audacity in trying to make something of herself. One volume among her books especially seemed to confirm this characterization: Flowers of Loveliness by Lady Blessington, about the author’s rise from a poor background and promiscuous lifestyle to become a countess through marriage to a nobleman. When the watchman at the scene removed the covering and showed her body to Bennett, he became oddly smitten. In his editorial, he made of it a strange Gothic scene, like a scene from a story by Edgar Allan Poe, in which he found her “beautiful female corpse” strikingly attractive. “’My God!’” he claims to have cried out. “’How like a statue! I can scarcely conceive that form to be a corpse.’” Three times in the article he compares her body to a polished marble statue, claiming he was “lost in admiration of this extraordinary sight.” The description seems less than forthright. It makes no mention of the blood from her wounds and describes the damage by the fire as providing only a bronzing effect to one side of this otherwise white marble sculpture. Whether or not his description was accurate or his reaction to the sight genuine, Bennett’s coverage of the murder resulted in a great increase in sales for his newspaper. Bennett’s tasteless exhibition of Jewett’s beautiful corpse turned out to be his path to success, and he had no intention of letting it go.

During the ensuing months before the trial began in June, Bennett published article after article about Jewett’s murder, and other papers, seeing his success, followed suit, although sometimes taking an alternative view of the crime. While Bennett would go on to raise a variety of alternative suspects to Robinson, even endorsing a widespread conspiracy theory that Robinson had been framed in order to protect the real killer, a more wealthy and powerful client of Jewett, other papers tended to favor Robinson’s guilt. While Bennett portrayed Jewett as a glamorous figure of great beauty who had often been seen on New York streets in her silk green dress and fine jewelry, others suggested she was actually rather ugly and overweight. Bennett portrayed her as a confident and intelligent young woman who had rejected a domestic life in favor of freedom both financial and sexual, but others described her as a depraved and manipulative harlot who had rejected morality and paid the price. One thing that most coverage agreed upon, though, was that Helen Jewett, whom many newspapers called Ellen through some error, had previously been on a more traditional path in life, with more socially acceptable opportunities, but had been seduced away into a life of vice, making the story of her murder a powerful cautionary tale. Among the numerous versions of her life appearing in newspapers and afterward in pamphlets sold on the streets, some sense of her true biography can be discerned. One version had it that her real name was Maria Benson, an orphan of Boston with a kind guardian who had sent her away to a boarding school where a lustful merchant’s son had taken her innocence. Rather than bring shame to her guardian, she left for New York, hoping to find work, but was taken advantage of again by a man who ended up installing her in a brothel. This story, though, turns out to have been a lie that Helen herself invented a couple years before her murder and told in court to elicit sympathy when pressing charges against a young man who had assaulted her. Nevertheless, there appear to have been some element of truth in it. Alternative accounts also tell us she was orphaned and raised in the family of a guardian before her unfortunate seduction while away at boarding school, but rather than being from Boston, she was from Maine, and her guardian was a Judge named Western. One of these accounts suggest her seducer had actually drugged her to take her innocence, and that she ran away to Boston thinking herself too befouled to remain a part of Judge Western’s family, though the good judge was said to have searched for her. Another claims she was engaged to be married, but when her betrothed left town, a young rake forged letters claiming her fiancée had died and, under the pretense of accompanying her to some distant family, abducted her, took her innocence, and left her in a brothel. In yet another version, she was not trafficked as a prostitute but rather sought out the vocation herself with enthusiasm and succeeded in establishing herself among a clientele of young men from wealthy families who became enamored of not only her beauty but also her wit and intelligence.

A salacious depiction of Jewett’s exposed body in her burned bed. Public Domain image.

So obsessed with her was Bennett that it was he who ended up discovering the closest thing to the truth about Helen Jewett. Through one of her confidants, he learned that she was named Dorcas Dorrance, and she was from Augusta, Maine, where her parents had died when she was a baby. She had indeed been raised by a Judge Western like a sister to his daughters, and was thus well-educated. When she was sixteen, while on a trip to visit some distant family, she fell in love with a young bank cashier and gave up her innocence in a moment of passion. After the Judge’s family learned she had lost her virginity, she left in shame and became a prostitute, first in Portland, then Boston, and finally in New York. Bennett’s account was widely reprinted, and as it spread, so too did a rumor that the young man who took Helen’s, or rather Dorcas’s, virginity was actually one of Judge Western’s sons. This finally caused the true judge, Chief Justice Nathan Weston of the Maine State Supreme Court, to issue a statement, declaring he was the Judge Western of newspaper reports, and that his family had been slandered. Helen Jewett’s true name was Dorcas Doyen, he said, and after her mother died, he had not adopted her but rather taken her on as a servant, for her own father was a drunk. She had not been seduced, said Chief Justice Weston, but had chosen herself at age 17 to pursue a life of vice. But even this revelation does not make for a certain understanding of Jewett’s character, for others have suggested the judge chose to impugn her character in order to save face for his own family. It turns out that in 1830, the same year that the judge said Dorcas left them, one of his daughters discovered that her husband had been having an affair, a discovery that would later be used as grounds for their divorce. Was it possible that young Jewett’s seducer had been a son of the judge after all, a son-in-law? Had she been forced out of the household and driven into a life of prostitution at the insistence of the judge’s daughter, or by the judge himself, holding her to blame for the son-in-law’s infidelity? Or had she in fact seduced the husband of her employer’s daughter? What we find is that Helen Jewett, sometimes called Ellen Jewett, formerly alias Maria Benson, once an orphan named Dorcas Dorrance, or rather Dorcas Doyen, could be made into whatever the public wanted her to be: a hapless victim of male depravity, an intelligent woman who liberated herself from society’s expectations, or a wanton seductress who met an unsurprisingly grisly end as a result of the vicious life she had chosen. In this way, Helen Jewett became more legend than woman, and as typically happens with legends, she was scorned by many and revered by some.

The attention of the penny press to the Robinson-Jewett case and the crafting of a legendary Helen Jewett resulted in an early form of street demonstration and a kind of protest movement. Every day, crowds gathered at Bellevue jail, where Robinson was held, and at the Thomas Street brothel where Helen had been murdered and where, according to one of Bennett’s reports, her ghost could sometimes be glimpsed in a window. These crowds were divided into two groups, which could be discerned by their attire. Those who revered Jewett and wanted to see justice for her murder began wearing white fur hats with ribbons of black crepe, a style of headwear that came to be called a “Helen Jewett mourner.” Meanwhile, the young working-class men who believed Robinson was innocent and that, as Bennett’s Herald was known to suggest, the authorities were engaged in covering up for some more privileged and wealthy murderer, wore another style of hat called Robinson caps, as well as cloaks with a fringe like that which was being used as evidence against the young man they believed was innocent. Both of these were largely gangs of young men, just the sort that were blamed by moral reform societies, many of them female societies, for the kind of vice and violence that was corrupting the city and had led to the crime. In those years, many teen boys were sent to live without supervision in cities while they learned the ins and outs of some business as a clerk, just as young Richard Robinson had been. These numerous young men were often blamed for the vice and disorder in the city, whereas young women, who typically lived under supervision, were not. However, it was not just young men who were influenced by the story of Helen Jewett. Her story had been so sensationalized, her lifestyle so glorified as an alternative to domestic pursuits and factory work, that there were reports of girls running away from home at 15 years old and attempting to enter brothels, believing it was their ticket to a “fancy life.” In fact, so venerated had Helen Jewett become among some women that when her partially burned bedstead was finally hauled out of the Thomas Street brothel and left at the curb for junk, a mob of young women fell upon it, prizing away pieces of it to carry with them as if it were the True Cross.

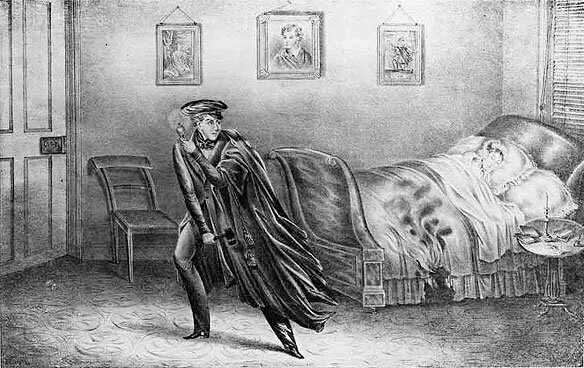

A depiction of a guilty Robinson fleeing the scene of the murder. Public Domain image.

The wearers of Robinson caps and cloaks showed themselves to be a true menace, proving the moral reform societies right about the dangers of lawless young men running amok in the city. While some ministers in the city preaching about the evils of prostitution suggested that Robinson had performed a public service by ridding the world of Jewett, the young Robinson-supporters on the street took that awful sentiment further and acted on it. During the months before the trial, violent assaults by young clerks on prostitutes and other young women increased sharply, and afterward, numerous copycat crimes were perpetrated, perhaps by young men who wanted to be like Robinson or who hoped to convince the public that he had been innocent all along, since the real killer was still out there murdering. To that end, an anonymous letter taking credit for the crime was sent to Bennett, who promptly published it in the Herald. According to this letter, the murderer was another young clerk who had been rejected by Jewett and made an enemy of Robinson, giving him motive both to murder her and frame him. Rival newspapers accused Bennett of forging the letter, which may have been the case, but Robinson supporters were writing letters a lot those days. They sent letters, for example, to Rosina Townsend, the brothel madam, threatening harm to her if she testified, for they believed she had been paid off by the conspiracy to frame Robinson. And they certainly weren’t all talk, either. They broke up a meeting of the New York Moral Reform Society that was convened to discuss the Robinson-Jewett case by throwing stones at the women who had gathered there. And on May 24th, a mob of several hundred young Robinson supporters attacked a group of prostitutes as they left the courthouse in an attempt to intimidate them so that they would not testify at trial. Even during the trial itself, young clerks wearing Robinson cloaks and caps filled the courtroom, making lewd comments about prostitutes who approached the bar to testify, booing and hissing any witnesses against Robinson, and cheering for any testimony that helped to exonerate him. It seems altogether to have been a circus of a trial, resulting in Richard Robinson’s acquittal. However, this disturbance by his rowdy young supporters was not the only reason that Robinson would be acquitted.

The case against Robinson was circumstantial. The madam, Rosina Townsend, testified that Robinson had arrived at the brothel before 9pm, and the roommate, James Tew, testified that he had returned home before 1am. To my mind, there is a problem with this timeline, though, since the fire was discovered by Townsend around 3am, and it had not consumed much of Jewett’s bed or done much damage to her corpse, suggesting it had only recently been set. If Robinson had indeed set the fire before returning home at 1am, it would have had to be a very slow smoldering one not to be detected for two whole hours. However, this does not seem to have been Robinson’s line of defense. Rather, his attorney concentrated on establishing a more ironclad but apparently bogus alibi. They were able to get a respected store owner, one Mr. Furlong, to swear that Robinson had been at his store downtown at around 10:30pm, which if true would disprove the testimony of the brothel madam that he was in Helen Jewett’s room at that time. In truth, Mr. Furlong’s testimony not only contradicted Rosina Townsend’s testimony but also the statements of James Tew to the nightwatchmen the morning after the murder, when he said they had indeed visited the brothel together the night before. However, the judge instructed the jury to base their decision on the fact that either Mr. Furlong or Ms. Townsend were lying and implored them to consider the reputation of each witness in their decision. As a result, the jury predictably chose to believe the upstanding store owner over the brothel madam and took only 15 minutes to acquit Robinson. After the trial, though, one Mr. Wilson published a letter swearing that he had been present in Furlong’s store that Saturday night when Robinson was present, and it had not been any later than 8pm, which made it no alibi at all since the timing would no longer contradict Madame Townsend’s testimony. So Robinson was acquitted on what appears to have been dubious testimony, and thus was believed by many to have gotten away with the murder.

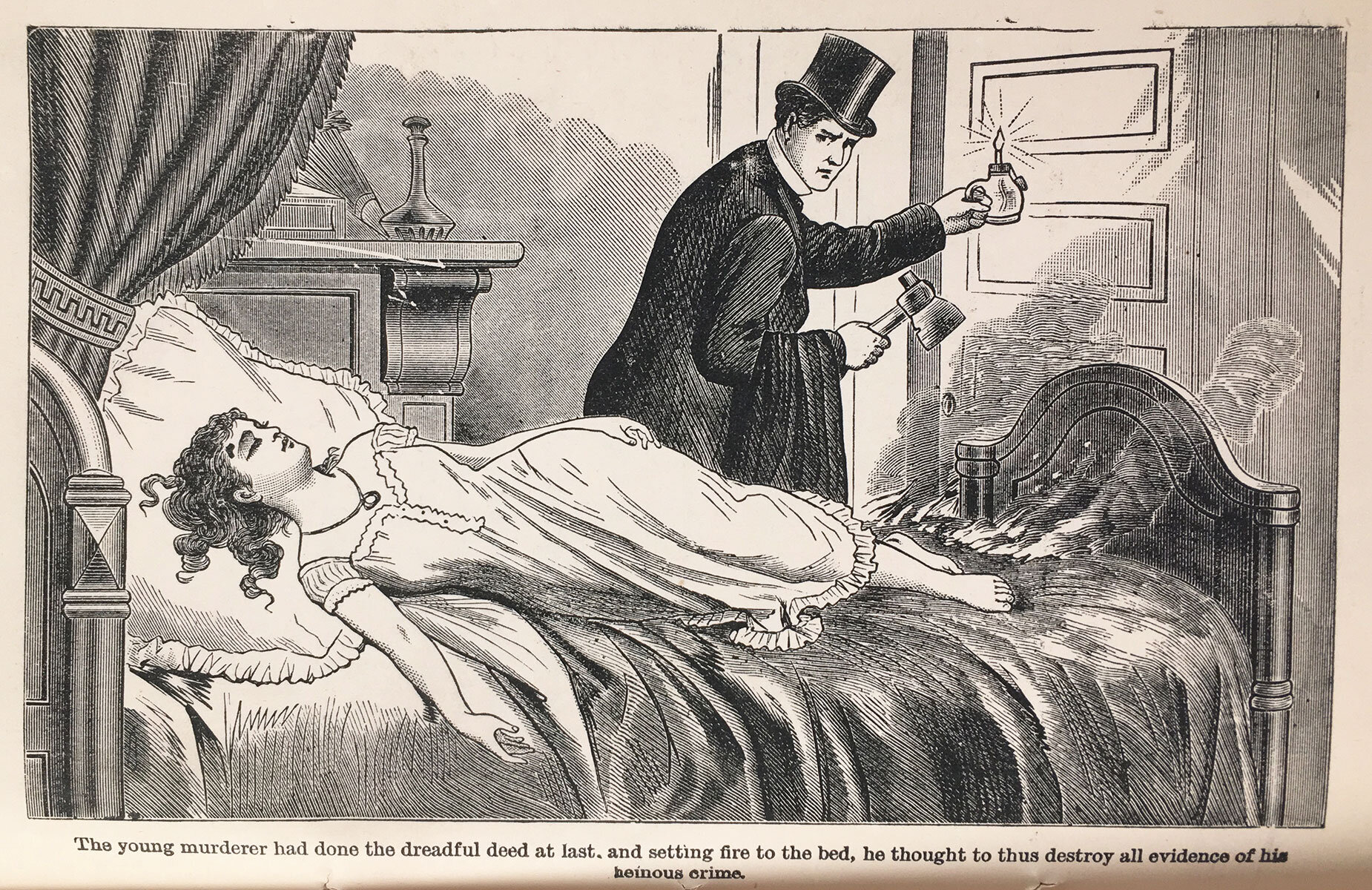

A depiction of Robinson looming over Jewett with the murder weapon. Public Domain image.

The fact is, though, that even without this false alibi on which Robinson’s lawyer had staked his fate, the case against Robinson was weak. The motive attributed to him was borne out of nothing but public rumor that Robinson was engaged to marry and had murdered Jewett because she had threatened to expose their relationship to embarrass him. Other, better corroborated rumors of how Robinson explained the entire scenario to close friends casts the entire affair in a different light. Robinson supposedly told confidants that he had resolved to stop visiting her, but Jewett, who had become enamored of him, begged him to visit her at least once more, on that Saturday, to which he agreed. A couple of days before their final assignation, Robinson had been working at the store where he clerked, opening boxes with the hatchet in question, which he remarked to a porter at the time was too dull to cut. He took the blunted hatchet with him, keeping it inside his cloak, meaning to have it sharpened that Saturday night, and on the way, he stopped at the brothel to keep his date with Helen Jewett. According to this story attributed to Robinson, he stayed with Helen until it was too late to get the hatchet sharpened. Helen begged him to come back for one more visit, pointing out a tear in his cloak that she said she could mend for him. Eventually, he acquiesced, leaving the cloak with her and the hatchet as well so that he would not have to carry it home and back again. Of course, this elaborate story, which his lawyer never had him tell in court and which appeared in a letter of uncertain authorship, could merely be a complex lie to allay the suspicions of those closest to him, if it were written by him at all, but according to a later New York Times article about the case, the porter at his store confirmed that he had indeed taken the hatchet to have it sharpened. Still, this may have been Robinson’s cover story for getting his hands on a weapon with which he could do away with Helen Jewett, but Robinson’s character and demeanor were a constant testament to his innocence. According to the nightwatchmen, he was emotionless upon seeing her body, yes, but also according to them, he appeared entirely unworried and when they came to his apartment that morning, appeared to have been sleeping soundly, coming with them without any apparent anxiety, seemingly entirely ignorant of the crime for which later that morning he would be arrested. Moreover, for the rest of his life, he consistently contended his innocence, even coming back to New York some twenty years after the trial and visiting the lawyer who had gotten him acquitted in order to reaffirm to his former counsel that he had indeed been innocent, though he said he did not expect to change the attorney’s opinion of him, whatever it might be. I’m no abnormal psychologist, but this doesn’t strike me as the behavior of a killer who narrowly escaped justice but rather as the behavior of an innocent man whose name had been permanently and unfairly maligned.

So the question must inevitably be addressed: if not Robinson, who had killed Helen Jewett and why? I won’t entertain the conspiracy theories that James Gordon Bennett printed about police coverups and witnesses being paid off to pin the crime on Robinson in order to protect another patron of Jewett’s, but I will consider the notion that Jewett received another visitor after Robinson had departed, a visitor of whose arrival Madame Townsend was perhaps not aware. As it turns out, another young clerk had also been investigated in the early morning hours after Jewett’s corpse had been discovered. This young man, whose false name at the brothel was Bill Easy, was the son of a Massachusetts judge. His name was George Marston, and he had a standing appointment with Helen Jewett on Saturday nights. However, it appears that Jewett had spurned him that Saturday night in favor of receiving Richard Robinson, whom she had begged to come see her on a night when perhaps they did not usually rendezvous, if his story was to be believed. Learning that Robinson had been the last to see her, the investigators Brink and Noble had focused on him, but what of Bill Easy? Is it not possible he had been angered by Jewett’s refusal to keep their appointment, that he may have come to see her later that evening, found in her room a cloak and hatchet belonging to a rival for her affections, and then committed the crime in a fit of jealous rage? It certainly seems feasible, and perhaps if more time had been spent looking into George Marston, aka Bill Easy, as a suspect, we would know better how believable it is. But the evidence at the scene led the watchmen to Robinson, perhaps purposely.

Another depiction of the murderer leaving Jewett’s bed ablaze. Public Domain image.

If we are to consider the possibility of a frame job, the suspect Rosina Townsend, madam of the brothel, comes better into focus. Bennett sometimes cast suspicion on Townsend in the New York Herald, suggesting Jewett owed her money. Putting aside the logic of murdering someone who owes you money and therefore never getting your money, and ignoring the lack of motive for framing Robinson beyond simply throwing suspicion away from herself, there is some reason to suspect Madame Townsend. According to her testimony, she woke around 3am and noticed light emanating from her back parlor, where she found a lamp near the back door, which was open. Recognizing the lamp as one of a pair kept in the adjoining rooms of Helen Jewett and another prostitute, Maria Stevens, she closed the door and went upstairs to return the lamp. Maria’s door was locked, so she tried Helen’s and found the room full of smoke, whereupon she shut the door, pounded on Maria’s door to rouse her, and went to the street door to call for help, her cries summoning the nightwatchmen Brink and Noble. However, according to the New-York Daily Times, she told the first watchman to arrive that there was “a girl murdered up stairs,” even though later her story was that she had only opened the door and seen the smoke inside. It was also she who led the watchmen to the back yard, she who pointed out the hatchet to investigators, and she who first looked over the fence and spied the discarded cloak. If there was any person on the scene trying to make sure Robinson was framed for the crime, the brothel madam certainly fits the bill.

Lastly, there is the other prostitute whose room adjoined Helen Jewett’s, Maria Stevens. It must be remembered that, according to Townsend, a lamp belonging either to Helen or Maria was found by the open back door, prompting Townsend to go up to their rooms. It is unclear whether Maria’s lamp was still in her room, or whether Helen’s was missing from hers, or whether this was ever investigated. It is somewhat suspicious, perhaps, that upon seeing the smoke in Helen’s room, when Madame Townsend knocked on Maria Stevens’s door, she apparently emerged immediately, as if she were not actually sleeping at all. According to the New York Times, Maria Stevens even had something of a motive. Richard Robinson had been a regular visitor of Maria’s before the enchanting Helen Jewett had arrived. According to this narrative, Richard Robinson was just an all-around heartbreaker, causing Maria Stevens to fall in love with him before he spurned her for Jewett and captured her heart as well. By this telling, Maria Stevens crept into Helen’s room late at night, butchered her where she lay with Robinson’s blunt hatchet, set her bed on fire, and then crept by lamplight downstairs to discard Robinson’s things in the back yard. Granted, it seems odd to then return back upstairs in the dark without the lamp and lie in wait next door to the fire she had set, hoping someone would notice the blaze and wake her. Then again, perhaps she did not start the fire until after she had gone downstairs to toss the hatchet and cloak. Either way, though, the end of Maria’s story does indeed make her a strong suspect. While Richard Robinson moved to Texas and became a successful business owner, and Rosina Townsend closed the brothel and retired to a small village near Albany for a quiet life with a carpenter husband and an active role in her local church, Maria Stevens committed suicide two weeks before the Robinson-Jewett murder trial began.

A depiction of Helen Jewett’s beauty published after she had become a legend in the public imagination. Public Domain image.

Among all these twisting intrigues and competing theories floats the apparition of Helen Jewett, looking down on all the ruckus in the New York City streets just as her ghost was said to peer from the brothel windows on the crowds below. And she remains to us today no less spectral than to the rowdy crowds that gathered in the summer of 1836 in their Jewett mourners and Robinson caps. She was variously idolized as a heroine, scorned as a Jezebel, and mourned as a martyr, but who was she really? The newspapers that mythologized her weren’t writing about the real her. They competed with each other to uncover her birth name, but they couldn’t even be bothered to get her chosen name right, calling her Ellen instead of what records show she called herself, Helen. We do know she was young, around 23 at the time of her murder. We know she had gone from living in the home of a Supreme Court Judge in Augusta, Maine, to living in a brothel in New York City. And we know that she had not only inspired desire in numerous young clerks working in the city, but also that she aroused a violent anger, for during the trial, the prosecution revealed the existence of some letters to Helen Jewett that explicitly threatened to murder her. The prosecutor failed to prove the handwriting was Robinson’s, and so was forbidden to read the letters aloud to the jury, but this fact paints a further picture of Helen Jewett’s life. Of modest birth, she had had a taste of comfort and wealth. Thereafter finding herself on the street, and whether forced into it or seeking it out, she saw a path up from the gutter through the sex trade. She navigated the class structures of New York City society by leveraging her body and exploiting the lust of unsupervised young men with money in their pockets, but along the way, she made enemies, perhaps because she inspired jealousy in those who wanted to keep her from rising above their level, or in those who resented her freedom and wanted her all to themselves. But now I am speculating, much as Bennet and other newspaper editors did in 1836. The beautiful corpse of Helen Jewett still seems to stir the imagination 185 years later.

Further Reading

Anthony, David. “The Helen Jewett Panic: Tabloids, Men, and the Sensational Public Sphere in Antebellum New York.” American Literature, vol. 69, no. 3, 1997, pp. 487–514. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2928212.

Cohen, Patricia Cline. “The Helen Jewett Murder: Violence, Gender, and Sexual Licentiousness in Antebellum America.” NWSA Journal, vol. 2, no. 3, 1990, pp. 374–389. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4316044.

“The Ellen Jewett Tragedy: Death of Richard P. Robinson—Reminiscences of the Ellen Jewett Murder.” The New-York Daily Times, vol. 4, no. 1231, 29 Aug. 1855, p. 1. The New York Times, www.nytimes.com/1855/08/29/archives/the-ellen-jewett-tragedy-death-of-richard-p-robinsonromints-the.html.