Gun Violence in America

In Manhattan, in January of 1911, satirical novelist and muckraking journalist David Graham Phillips took his usual route from his Gramercy Park apartment to the Princeton Club, a private club for the Ivy League university’s alumni. Phillips cut a tall, impressive figure, wearing light summer suits in winter, handsome with striking pale eyes. When he arrived at the club, a man he did not know approached him, lifted a handgun, and fired several bullets into Phillips, crying out “Here you go!” before shooting himself in the head. As Phillips slowly died from his gunshot wounds, he expressed confusion about who his murderer had been, but police had little trouble determining the motive, remembering that Phillips had not long ago come to them about a series of threatening letters he’d received. His killer was Fitzhugh Goldsborough, the deranged son of a wealthy family whom he believed Phillips was lampooning his fiction, some of which satirized rich, entitled youth. The coroner who examined their corpses, who regularly corresponded with the press to offer them grisly statistics on New York deaths, afterward spearheaded a campaign against the easy acquisition and public carrying of concealable handguns, a campaign that was met with much public support. Just five months before the murder/suicide outside the Princeton Club, a dockworker had shot popular New York Mayor William Gaynor in the neck. Gaynor had survived, but the incident had touched off a robust debate about whether mental illness, or the media, or our national culture had contributed to the crime. After the Phillips murder, the debate shifted to focus on the fact that a disgruntled and violent individual had been so easily able to acquire a gun and carry it to the marina where the mayor was waiting to board a steamship. The push for gun legislation in 1911 was further championed by a State Senator named Timothy Sullivan, who framed the campaign as a solution to gang violence. The reign of terror of certain street gangs was very real to New Yorkers. Less than ten years earlier, the Jewish-American-dominated Eastman Gang of the Lower East Side had clashed with the Italian-American dominated Five Points Gang in a bloody shootout on Rivington and Allen Streets. When police arrived, the two gangs turned their guns on the officers. The streets had been transformed into a warzone, and in the intervening years, the gang wars had continued. Senator Sullivan introduced gun control legislation in 1911 that instituted licensing for the possession of any firearm and left the decision of whether to issue a carry license up to the licensing authority, the police, who rarely granted the privilege of carrying firearms in public. This gun control law has been criticized as a way for Tammany Hall politician Timothy Sullivan, portrayed by his rivals and critics as a crime lord himself, to have his adversaries arrested by having firearms planted on them. Indeed, it’s been said that some street toughs took to sewing their pockets shut so that police could not plant handguns on them. It has also been argued that police racially-profiled members of immigrant communities when enforcing the law, which certainly seems to be the case. The first man imprisoned under the law was an Italian, and in an editorial after his conviction, the New York Times praised the judge for the 1-year sentencing, saying that it “suitably impressed the minds of aliens in New York that the Sullivan law forbids their bearing arms of any kind,” while also, to their credit, asking, “would it not be well to ‘get after’ the notorious characters who are not aliens?” and conceding that “’frisking’ such persons is less common, perhaps, than it ought to be.” Regardless of such ulterior motives or corrupt enforcement policies, though, the Sullivan Law shows us that there was a time, before the rise of the powerful gun lobby, that gun violence could be responded to with reasonable gun control legislation. While there is evidence that this law greatly reduced suicide rates, there is no evidence that it reduced New York homicides, and certainly it did not prevent Payton Gendron from legally buying a Bushmaster XM-15 assault rifle at a gun shop in Endicott, New York, and opening fire on the patrons of a Buffalo supermarket in the recent racially-motivated massacre. I would argue, though, that it is difficult to quantify what heinous crimes by mentally ill individuals might have been prevented just because they were discouraged by the licensing process. But regardless, what the law shows us is that, a hundred years ago, it was not portrayed as un-American to consider gun control legislation in order to reduce gun violence. But as I sat down to write this, it was in the news that the conservative activist justices packed onto our Supreme Court, who also just overturned established precedent in order to reduce civil liberties and rescind reproductive rights, have also ruled this New York gun control legislation unconstitutional. And they have done this in the wake of the most heinous school shooting since the Sandy Hook Massacre, just one month after nineteen children and two teachers were shot dead at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. To put a little perspective on this, the same gun rights activists who protest the push for sane gun control measures in the wake of every mass shooting, arguing that it’s more appropriate to mourn quietly than to demand real social change after such a tragedy, are simultaneously applauding the erosion of established firearms legislation during a mass shooting’s aftermath. This is Historical Blindness. I’m Nathaniel Lloyd. And I don’t want to hear that “Now is not the time” evasion. It is long past time to talk about Gun Violence in America.

Welcome to Historical Blindness. Whenever a gun rights proponent tells you that it’s not appropriate to discuss change or legislation in the wake of some gun violence, they are displaying a clear blindness to history. In modern America, that is the only time when significant gun control legislation has ever been passed, and it used to be that the Nation Rifle Association supported such legislation and even helped draft it. Among these reactive gun control measures were the 1934 National Firearms Act and the Federal Firearms Act of 1938. These measures were enacted in direct response to the gangland gun violence of the Prohibition Era and mass murders such as the St. Valentines Day Massacre of 1929, when seven Irish gangsters were stood against a garage wall and gunned down. The more direct impetus, though, was the attempt of a lone gunman on Franklin D. Roosevelt’s life in Miami in 1933, when he was President Elect. The attempt failed, though the Mayor of Chicago was killed in the hail of bullets fired by the assassin. Recently, a conspiracy theory emerged that the assassin was working for the mafia and that the mayor was his true target, but at the time, the fact that a lone fanatic with a revolver bought from a pawn shop could come so close to ending his life put a fire under Roosevelt to push for gun control legislation. At first, the National Firearms Act was intended to require the registration and prohibitive taxation of all firearms, including handguns like the one that had nearly killed Roosevelt, but in the end, it ended up only focusing on “gangster weapons,” including machine guns and short-barreled shotguns and rifles. The later firearms act of 1938 made licensing a further requirement of gun sellers, and prohibited the sale of firearms to certain persons, such as felons. The NRA again supported these measures. They were, after all, founded as a sporting and marksmanship club focused on promoting gun safety. In fact, the year after the 1938 legislation was passed, the President of the NRA, Karl Frederick, stated “I have never believed in the general practice of carrying weapons. I do not believe in the general promiscuous toting of guns. I think it should be sharply restricted and only under licenses.” 30 years later, in the wake of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, after learning that Lee Harvey Oswald had acquired the murder weapon through the mail on the cheap with an NRA coupon, the NRA agreed that the mail-order sale of guns must be prohibited. And again, after the further assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., the NRA was very involved with the drafting of the Gun Control Act of 1968, which replaced and updated the two existing firearms acts, introducing serial numbers, a minimum age for gun ownership, a restriction on sales across state lines, and the prohibition of sales to known drug addicts and the mentally ill. What those without historical blindness must see is that there is a long history of passing gun control measures in response to acts of gun violence, and that the NRA used to champion the gun control legislation that today they call unconstitutional.

The aftermath of the attempted assassination of Roosevelt in Miami, when Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak was shot.

Although the NRA supported and helped craft the Gun Control Act of 1968, we see the beginning of their transformation about this time, as they used their influence to block the most sweeping of the bill’s measures, including the licensing of all gun carriers and a national registry of all firearms. President Lyndon B. Johnson called them out for this in a speech, saying “The voices that blocked these safeguards were not the voices of an aroused nation. They were the voices of a powerful lobby, a gun lobby,” and within a couple years, the entire platform of the NRA would change after an ill-fated raid by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, during which an NRA member who was believed to be stockpiling weapons illegally, was shot and paralyzed. After that, the NRA began to oppose any federal enforcement of gun control legislation, and began to tout the Second Amendment as a protection of an individual’s right to keep and bear arms, which it was never intended to be. I’ll explain and support this further later in the episode, but suffice it to say that the argument of individual gun rights being protected by the Constitution never even came up in the debate over the sweeping gun control legislation of the 1930s, and such rhetoric had previously been the domain of militant groups like the Black Panthers, whom the NRA had vehemently opposed and whose supposed right to publicly carry firearms they refused to recognize when just a couple years earlier, in 1967, they had supported the Mulford Act in California, a bill to prohibit the carrying of loaded firearms publicly without a permit. Ever since this turn to the right in the 1970s, when new leadership set out to become the obstructive political force they remain today, the NRA defined and constructed gun ownership as a social identity, and for many gun owners, including some close family members of mine, it is one of the major pillars of their personal identity. They cultivated this notion of gun ownership as a social identity principally through their longstanding publication, American Rifleman, and thereafter politicized this social identity, such that support for gun rights has become a conservative Republican litmus test. Because of the NRA’s influence on their constituency, as well as because of their large campaign contributions, the major political figures and media apparatus of the right have further encouraged the notion of gun ownership as a distinct and legitimate social identity, one that Republicans claim as their own. Like the modern Republican Party generally, seemingly devastating scandals have arisen that should have caused the NRA’s dissolution entirely. After the 2016 election, it was revealed in a U.S. Senate Committee on Finance Minority Staff report that the NRA had become a Russian asset in its election meddling campaign, demonstrating that NRA officials sought out Russian money and facilitated the political access of known Kremlin agents, including Maria Butina. Republican apologists for the NRA argue that they were acting as individuals rather than on behalf of the NRA, but subsequent investigations by the New York Attorney General have revealed widespread fraud and cronyism in their organization. But the NRA simply left New York for Texas, declaring bankruptcy, and appears to be no less influential after these scandals. As one President who took money from them to further their agenda once said of himself, they could probably shoot somebody on Fifth Avenue and not lose supporters.

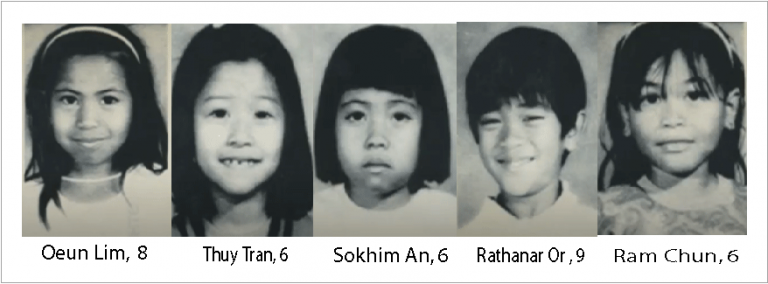

Despite the growing power of the NRA to kibosh any gun control legislation, they have been unable to stop certain major gun control legislation, especially when it is enacted on a wave of outrage after an infamous act of gun violence. Early on they even found themselves at odds with their Republican allies. After he was shot by John Hinckley, Jr., in 1981, Ronald Reagan supported the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, more commonly known as the Brady Bill, which mandated background checks and a waiting period. By the time the act was passed, the NRA was able to get the five-day waiting period replaced by an instant computer background check, and until such a system could be put in place, they sought to fight the mandate. They financed a series of lawsuits in an effort to take the bill to the Supreme Court, which they succeeded in doing in 1997, winning an opinion that compelling law enforcement to run background checks was unconstitutional. The decision had little effect, though, since state and local law enforcement mostly chose to continue running the background checks of their own accord, and soon the background check database was in place. By this time, though, there was a much broader piece of gun control legislation for the NRA to fight, this one too passed in the wake of an act of gun violence that could not be ignored. On January 17th, 1989, a station wagon full of fireworks that had been parked behind Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton, California, not far from my own home town, was set on fire, creating something of a distraction as a deranged and suicidal drifter in a flak jacket named Patrick Purdy set foot on the school’s playground, took position behind a portable building with an AK-47 that he had acquired quite easily at a gun shop in Oregon, and started firing. He wounded more than thirty that day, and he murdered five children before taking his own life. The unthinkably heinous act resulted in numerous pieces of gun control legislation. In California, the Roberti-Roos Assault Weapons Control Act of 1989 prohibited the transfer and ownership of more than 50 different semi-automatic assault weapons, the George H. W. Bush administration banned the importation of assault weapons that the ATF determined had no “sporting purpose,” and in 1994, a Federal Assault Weapons Ban was passed along with the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of that year. The Assault Weapons Ban prohibited large capacity magazines and, much like the California law, banned the manufacture of specific semi-automatic assault weapons for use by civilians. Rather than restrictions on handguns, it is measures like these, meant specifically to fight mass public shootings, that gun control advocates have been urging after every mass shooting for the last 20 years. We have had them in place before, and it did not result in tyranny. The only reason we must advocate for these restrictions again is that the Assault Weapons Ban had an expiration date, and in 2004, it was not renewed.

Portraits of the children murdered by Patrick Purdy, from clevelandschoolremembers.org

Let us look further at the ten years 1994 to 2004, when the Federal Assault Weapons Ban was in place. Perhaps this seems rather a recent time period for a history podcast to be discussing, but since gun rights proponents act like banning assault weapons would spell out certain doom for our democracy, it seems memories are so short that we must remind many that less than 20 years ago we had such a federal law and it wasn’t the end of the world. In fact, it appears to have had a measurable effect on gun violence. The entire rationale behind the ban was that violent incidents involving assault weapons and high-capacity magazines typically involve more shots, more victims, and more wounds, and statistics support this assertion. Rather ridiculously, assault weapon apologists argue that the recoil of these weapons means worse aim and thus we cannot assume assault weapons are better able to strike more people. If that were the case, of course, it just makes them even more useless for sport or home defense, rendering them suitable only for spraying rounds into crowds. In other words, it just proves they are unsuitable for civilian use and especially dangerous in the hands of a mass murderer. Critics of the Assault Weapons Ban also claim it had little to no effect on crime, but the hard data disputes this. According to a 2001 study of the impacts of the ban in the Journal of Quantitative Criminology, not only did criminal use of assault weapons decline in the years after the passage of the Assault Weapons Ban, but gun murders generally declined around 10%. Critics contend there is no proof of causation, that this reduction in gun homicides may have been due to other factors or the cyclical nature of crime stats, but since the ban’s expiration, the share of crimes involving high-capacity semiautomatics has increased from 33% to 112%, according to a 2018 study in the Journal of Urban Health. Still, mass shootings continued to occur during the years of the ban, including one of the worst school shootings in our history, the Columbine High School Massacre of 1999, whose perpetrators used weapons that remained unbanned, including a variant of the banned semiautomatic TEC-9 pistol that because of its slightly different name, the TEC-DC9, remained legal. Rather than proving that the 1994 Assault Weapons Ban was pointless, though, this instead proves that it was, if flawed, still working, and rather than abandoning it, such a ban should be improved, and such loopholes closed. Looking closely at data on mass shootings collected by Mother Jones, we can see that 18 mass public shootings occurred during the decade before the ban, while 15 mass shootings occurred during the ban. The difference between these decades may not appear striking, but let’s look at the decades since the ban’s expiration. During the ten years after its expiration, mass public shootings more than doubled, to 36, including the devastating Viginia Tech and Sandy Hook Massacres. And in the following 8 years, up to today, 61 mass shootings have occurred, and actually more, since Mother Jones’s data ceases in mid-June and these horrific crimes seem to be perpetrated weekly at this point. (In fact, as I was editing this podcast episode, I was compelled to record this insert to acknowledge that on Independence Day, a shooter in Highland Park, IL, injured 47 and killed 7 by firing at parade-goers with a high-powered rifle from a nearby rooftop. During the aftermath, a Republican state senator urged everyone to “move on.”) It is certainly true that not all of these mass shootings were committed using assault weapons, but almost all are committed using semiautomatic weapons with removable high-capacity magazines. As of 2017, according to the aforementioned study published by the Journal of Urban Health, “Assault weapons and other high-capacity semiautomatics appear to be used in a higher share of firearm mass murders (up to 57% in total).” Furthermore, a 2019 comparative study in the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery found that during the decade of the federal ban on assault weapons, mass shootings were 70% less likely to occur. But even if we were to discover that banning assault weapons and high-capacity magazines did not reduce the growing number of these mass shooting incidents, perhaps it would at least make a difference in the average number of victims, making such incidents far less deadly. There is no logical reason that I can see not to update, improve, and renew the Federal Assault Weapons Ban. Only conservative ideology and an entrenched, uniquely American gun culture stand in the way.

What makes America different from other Western democracies, and other nations generally, that we have developed this deep-rooted gun culture? Make no mistake, we are different. Among the top 10 countries that tolerate civilian gun ownership, we simply own more, at an estimated 120 guns per 100 residents, more than twice that of the next highest country in gun ownership, Yemen, according to the 2018 Small Arms Survey. When we look at gun murders as a percentage of all homicides in 2020, as reported by the BBC, it appears one is far more likely to be shot to death in America than in any other democracy of comparable size. In the UK, gun homicides made up only 4% of gun-related killings, unsurprisingly, considering the UK’s ban on military style weapons and handguns. In Australia, which passed sweeping gun control legislation after a series of mass shootings in the ’80s and ’90s, gun murders stood at only 13% of 2020 murders. In Canada, which generally ensures gun accessibility but maintains stricter controls of the same kind as the US, 2020 saw gun murders comprise 37% of the total. But here in the good ol’ U.S. of A., a whopping 79% of murders were gun-related. And probably because of our spotty and lax laws and the sheer number of guns in hands here, 73% of all mass shootings worldwide between 1998 and 2019 occurred here in America, as determined by a study in the International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice. Our reluctance to address this problem with strong legislation is also pretty unique. Take New Zealand’s response to the 2019 mosque shootings in Christchurch as an example. Within a month, the government had passed legislation banning semiautomatics and magazines, and within a few more months, they created a national firearms register and tightened restrictions on gun licensing. Their quick action to address the problem should make Americans feel ashamed of our own government response. We may be tempted to blame the NRA for this gun culture entirely, but that would be inaccurate. The connection between Americans and guns stretches back a long time before the NRA was ever formed in 1871 as a marksmanship club. Some have suggested that gun culture originated in the Wild West, when it is thought that every man must go about armed, and good guys with guns stood down bad guys with guns on a daily basis, but much of the tales of the American West are exaggerated. In fact, an opposing argument could be made that the Wild West was actually the origin place of American gun control laws, as Western towns nearly universally decreed that no one within town could carry a firearm, according to gun policy scholar Adam Winkler, and these “blanket ordinances” resulted in actually very low crime rates in such notorious towns as Deadwood, Dodge City, and Tombstone. Others might see the origin of American gun culture being related to the carrying of pistols by gentlemen, replacing the rapier around 1750 as the symbols of their masculinity, which they wielded in duels over perceived slights, but this fashion originated in Europe rather than the Americas. Certainly guns remain the phallic symbol of many an American male’s sense of manhood today, but in France and Britain, for example, where the most recognizable pistol dueling methods were established, the masculinity of men is no longer dependent on their gun ownership. So what makes American gun culture different?

Image of al old frontier town with the gun control ordinance clearly posted: “The Carrying of Fire Arms Strictly Prohibited.” Courtesy Saint Joseph’s University

Americans’ love affair with deadly weapons can be traced all the way back to our independence, and even earlier. Much can be attributed to the fact that early Americans were colonizers and frontiersmen. By frontiersmen, I don’t mean gunslingers. I mean settlers—farmers, hunters, trappers. Those who sought to tame the wilderness relied on firearms for survival and subsistence. Wild game was a major part of their diet, and occasionally they had need of a firearm for defense against not only some human aggressor, but a dangerous wild predator. Farmers too relied on varmint guns to dispatch vermin that threatened their crops and predators that threatened their livestock. During the many conflicts and skirmishes that can loosely be called part of the American Indian Wars, the average settler’s firearms were used to maintain possession of land they had taken in their encroachments on Native American territories, viewing themselves as acting in self-defense against marauding savages. Therefore, it was not uncommon for young boys to be given rifles as a symbol of their passage into manhood. The frontier and its dangers are long gone now, though, and have been for more than a hundred years, and other nations that began in recent history as a colonial settlement of wilderness, such as Australia, have proven better able to put down the wild gun culture that helped them tame their frontiers. No, America remains different, and this difference can be attributed to our Founding Fathers’ insistence that a right to bear arms is a God-given, inalienable human right—a right not recognized by any other Western democracy. How did gun ownership come to be viewed as a human right here and nowhere else? It all boils down to the politics of the American Revolution. In colonial America, English Whiggery was a popular political force, and the radical Whigs’ distaste for militarism contributed to revolutionary sentiment in America. According to this political position, “standing armies” represented the greatest threat and evil to man’s liberties. To American Whigs, George III’s stationing of troops in the American Colonies was an act of tyranny. After the Boston Massacre, when British soldiers shot five Americans in a crowd that was hurling insults, snowballs, and stones at them, John Adams called it “the strongest proof of the danger of standing armies.” This Whiggish aversion to standing armies, or to George III’s army in particular, is further reflected in the Declaration of Independence, which bemoans the fact that the King “has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures,” and can be seen to have still been on the minds of legislators years after the ratification of our Constitution, when they amended the Constitution to prohibit the quartering of soldiers in civilian houses. To radical English Whigs and American Whigs, or Patriots as they’re sometimes called, the solution to the evils of standing armies was a well-armed citizen militia, members of which could be trusted to act according to civic virtue. George Washington himself saw the folly of this early on, as he found the citizen militiamen under his command “incapable of making or sustaining a serious attack.” A historical myth has been perpetuated that America’s independence was won by the heroism of armed civilians, but in truth, militia troops performed quite poorly compared to Washington’s Continental Army. And after the Revolution, in their effort to bolster their citizen militia, our Founding Fathers endorsed gun laws that today would probably chafe even the most dyed-in-wool gun rights advocates: a 1792 law required all eligible men to buy a gun, report for muster, and register their weapons with the federal government.

It would not be long before the inadequacy of militia forces became apparent to all. In the War of 1812, when undisciplined militiamen embarrassed the country in failed stands against British troops, it became clear we needed to expand our own standing armies and could not rely on a militia. But by that time, the Constitution had already been amended with the Second Amendment, which states, “A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” I think most people know the argument in favor of gun control pointing out that this amendment only protects the rights of “the people,” meaning the country generally, to bear arms as part of “a well-regulated militia.” That much is apparent in the text. This “right” appears intended only to ensure the existence of a militia, not a well-armed general populace. What I don’t think many citizens realize is that this amendment, like the third amendment about quartering troops, is an artifact of an obsolete political view that America should rely more on militia forces than on a standing army. The fact that the U.S. promptly course-corrected after the War of 1812 and now has one of the largest militaries, and arguably the best equipped military, in the world, means this amendment is logically obsolete and should be subject to repeal and replacement. But even if one refuses to acknowledge that this amendment is only focused on strengthening and safeguarding militia forces, it actually explicitly urges regulation and in no way suggests that such regulation would infringe on the right being described. And it should be emphasized that this is not only the interpretation of modern gun control advocates. Until the latter half of the 20th century, it was the interpretation of legislators and the Supreme Court. In 1886, in their landmark decision on Presser v. Illinois, the Supreme Court held that “state legislatures may enact statutes to control and regulate all organizations, drilling, and parading of military bodies and associations except those which are authorized by the militia laws of the United States [emphasis mine],” clearly finding that the Second Amendment only applied to official national militias. In 1934, when Congress worked to restrict gangster weapons, the Second Amendment was not raised once during congressional testimony, clearly indicating that it wasn’t seen as relevant to such legislation intended to restrict individual access to firearms, and in 1939, when the law was finally challenged under the Second Amendment in the case of the United States v. Miller, the Supreme Court again ruled that the Firearms Act’s restriction of certain guns was entirely Constitutional, in that its provisions did not have any “reasonable relationship to the prevention, preservation, or efficiency of a well-regulated militia.” So there was strong judicial precedent here for the interpretation that the Second Amendment is not even about the individual rights of gunowners and therefore has no bearing on either state or federal gun control legislation. But just as today’s Supreme Court is bent on overturning established precedent based on ideology, conservative justices recently managed to overturn this decision as well. In the 2008 case of District of Columbia v. Heller, the Supreme Court decided in favor of the interpretation that the amendment protects an individual’s gun ownership rights, independent of militia affiliation—but even that ideologically split opinion, misguided as it may have been, confirms that “the Second Amendment right is not unlimited” and specifically seeks to preserve longstanding prohibitions on gun possession by felons and the mentally ill, and even suggests that the only firearms protected at those that were in common use at the time of the amendment’s ratification, leaving the door open for the banning of “dangerous and unusual weapons.”

The focus of the Second Amendment on a “well regulated militia” specifically reflects Whig politics at the time and the distrust of “standing armies,” much of which goes back to the Boston Massacre, pictured.

Rather than really contend with this argument about the true intention and purpose of the Second Amendment, though, gun rights activists employ fallacious arguments to present gun control as itself an evil. They will claim, rather absurdly, that the problems of gun violence can only be resolved with more guns, using the “Good Guy with a Gun” argument that if only more people were packing in any given gun crime situation, then criminals could be better stopped before they commit their acts of violence. According to this logic, an increase in unregulated exchanges of gunfire between civilians is viewed as a best case scenario and a solution to violent crime, and a society in which firearms have become as common as cell phones is dreamed of as the safest of societies, despite the obvious additional increase in suicides and lethal gun accidents that such a society would inevitably see. Really clever sophists will even twist history to make gun control laws look evil. These “twistorians,” if you will, point out that the first gun control laws were racist, disarming slaves and free Blacks in order to enforce White Supremacy. There is truth to this argument, which makes it rather insidious. Think of my episodes on the Wilmington Insurrection, when White Supremacists acted to prevent Black citizens from arming themselves against the violence that they were openly planning. The South, and even some Northern states, had always disallowed gun ownership among slaves and free Blacks, for the obvious reason that they feared rebellion, and following the Civil War, many Southern states adopted Black Codes that continued denying firearms to Black citizens. Enforcing this disarmament were armed white posses, called Regulators, who ran roughshod through Black communities. Some of these went about their marauding masked and called themselves the Ku Klux Klan. In fact, in the 1860s, legislation like the Freedmen’s Bureau Act and the first Civil Rights Acts, as well as the Fourteenth Amendment, were indeed intended, at least in part, to guarantee freedmen the same rights to bear arms in self-defense that their white oppressors enjoyed. Yet still, Southern states remained intent on disarming Black communities under Jim Crow. In the 1880s, faced with the growing scourge of lynching, Southern Blacks armed themselves and in several cases fought off bands of murderers. Through the end of the 19th century and the early 20th century, Black communities continued their tradition of arming themselves to fight back during race massacres, like those in Colfax, Louisiana; Wilmington, North Carolina; and Tulsa, Oklahoma. Even during the Civil Rights Movement, passive resisters were aided by armed community defense organizations. And the Black Panthers, as previously mentioned, were the OG gun rights absolutists. All of this is absolutely true, and yet entirely irrelevant to the self-evident fact that stronger background checks and laws prohibiting the ownership of high-capacity assault weapons are necessary to reduce mass public shootings.

While statistics on gun ownership are lacking without instituting a comprehensive national system of gun registration, according to Pew Research Center, as of 2017, white men are twice as likely to report owning a gun as non-white men. And I’m willing to go out on a limb and predict, in the absence of firm data on the subject, that it’s white men by far who possess high capacity assault rifles of the sort that most gun control advocates today want to ban in order to reduce mass public shootings. However, Black Americans far more commonly report having been shot or threatened with a gun compared to white Americans. The simple fact that, today, gun violence disproportionately affects Black Americans, making them 10 times more likely to die by gun homicide, and making their children 14 times more likely to be shot and killed according to the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, certainly highlights the fact that any reduction in gun violence achieved through stronger gun control legislation will logically save Black American lives. Let us not forget that many recent mass shootings, like the recent massacre in Buffalo, the 2021 shooting in Winthrop, MA, the 2019 shooting at a Walmart in El Paso as well as the Dayton, Ohio, Entertainment District shooting literally hours later, the 2015 shooting at Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston, and the 1999 Independence Day weekend spree killings across the Midwest, were committed by white supremacists as hate crimes against one race group or another. Times change. Gun rights used to be a racial justice issue, but now gun control is. Gun rights proponents who raise the issue of the racist origins of gun control either haven’t thought out their argument or are deflecting with a bad faith argument. No legislation to disarm some races and not others is proposed by advocates of stricter gun control, nor would any such legislation ever be passed as long as the 14th Amendment remains in place. So if these gun rights advocates are worried about inequality before the law and selective enforcement, about gun laws disarming minorities unfairly because of discriminatory implementation by authorities, then they are essentially acknowledging the existence of systemic racism, which, at the risk of stereotyping, a lot of these guys don’t really want to do, as fixing that would mean restructuring society, especially when it comes to the justice system and urban planning. We don’t fight systemic racism by refusing to pass necessary laws for fear they will be inequitably imposed; rather, we fight it by exposing and correcting the inequities themselves.

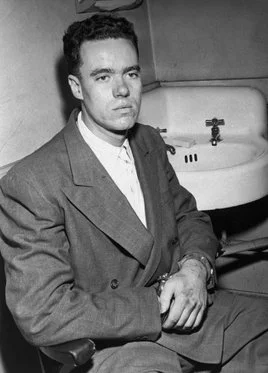

Howard Unruh, whose “Walk of Death” is widely regarded as the first mass public shooting of the modern sort.

The bare fact that mass public shootings have evolved since the time of our Founding Fathers, in ways they likely did not imagine, to become a unique societal evil today, stands as evidence that something must be done, and especially here, where it may not have begun, but where it is by far at its worst. The first mass shooting as we might define it today occurred in Hyderabad, in what is now Pakistan, in 1878, when an Iranian infantryman murdered his lover for her infidelity and then went on a shooting spree. However, the United States, shamefully, may be the origin of the mass school shooting. Some point to a massacre at a school during Pontiac’s War in 1764 as the first, but I would count that as a raid perpetrated by a band of Delaware during a time of war. Rather, the first genuine school shootings in U.S. history, according to our more modern understanding of such acts, occurred back to back in 1891, when one man attended a school exhibition in Liberty, Mississippi, and fired his shotgun into a crowd of students and teachers, and another man, only twelve days later, entered a parochial school in Newburgh, New York, and fired his shotgun at students on a playground. But it was not until the mid-20th century, 150 years after the ratification of the Bill of Rights, that the true horror of mass public shootings began to reveal itself, when Howard Unruh, a disturbed veteran, took his “Walk of Death” in 1949, strolling through his neighborhood and shooting thirteen men, women, and children dead. The 1960s saw mass shootings evolve to sniper attacks, when a California teen injured ten and killed three by taking potshots at vehicles on the highway with his father’s rifle before killing himself, and when a Marine sharpshooter perched in the University of Texas clock tower managed to murder fifteen people and wound thirty-one others before being killed by authorities. After a spate of mass shootings by deranged postal workers in the 1980s and ’90s, as well as since, the narrative around mass shootings was focused for a time on workplace shootings, and the term “going postal” was coined, referring to being driven to violence by anger and frustration related to one’s occupation. But today, mass public shootings have become so common, and have evolved with the weapons being used to become so much deadlier, that the old terms spree killing, postal killing, workplace shooting, sniper attack, and even mass murder, seem inadequate, either too narrow or too vague to really describe the problem. Mass public shootings are a national dilemma that the Founding Fathers just could not have anticipated. To use a frequently raised but I think apt analogy, the problem can be likened to automobile deaths. Because of the unsafe and sometimes reckless use of a technology that was not around at the framing of our Constitution or the ratification of our Bill of Rights, annual deaths in motor vehicle accidents were exceedingly high for a long time. Just as the gun lobby today resists regulation, automobile manufacturers then resisted vehicle safety legislation, but it was passed regardless, increasing safety standards for automobile manufacturers and requiring the installation of seat belts. Legislators recognized a uniquely modern public safety hazard and took legislative action to remedy it, resulting in a significant reduction of road fatalities. I guess we are just fortunate that, in that case, there was not some outmoded constitutional amendment about the freedom of saddle makers to decide on what safety straps to manufacture, or the rights of stagecoach drivers and carriage passengers to sit on their benches unencumbered by restraints.

To clarify my position, I am not urging total civilian disarmament. I firmly believe that the populace should have access to well-regulated firearms for home protection and sport. And I even have some sympathy for the central conviction of most gun rights advocates that the right to bear arms is an important safeguard against tyranny. But the threat of tyranny was far more imminent in the wake of American Independence, whereas today it only seems to fuel the baseless conspiracy fantasies of paramilitary militia men and seditionists. These gun rights advocates have feared an oppressive government declaring martial law for decades, imagining that every mass shooting is actually a staged “false flag” operation to be used as justification for a clampdown and a total disarmament of the populace that never actually occurs. For 8 years, the gun-toting right was certain that Obama intended to disarm the populace so he could establish some kind of socialist dictatorship. What really happened was that he urged the passage of sane gun legislation, which was killed by the Republican Senate minority through the abuse of the filibuster. In fact, the closest we’ve come to a President actually declaring martial law was when Obama’s successor, a gun rights advocate who took a lot of money from the NRA, looked into imposing martial law, not to take guns but rather to overturn lawful election results in a coup d’état. The hypocrisy of gun rights advocates who fear an oppressive government turning around and supporting a literal attempt to overthrow our government is profound. As is the hypocrisy of our conservative-packed activist Supreme Court bench, who defend the authority of state governments to interfere with women’s bodily autonomy but deny the authority of a state government to regulate firearms. The fact is, gun control must be viewed as a pro-life issue, as the Catholic Church has long argued. Those who believe themselves the moral champions of life need to start advocating for the protection of it after birth. The fact that we, as a country, did not come together to protect our children from mass shootings after Sandy Hook, and that now, after the recurrent horror that occurred at Uvalde many continue to resist, is a national shame. And it will only get worse if we don’t wake up and smell the blood of our children.

Further Reading

“America’s Gun Culture – in Seven Charts.” BBC, 25 May 2022, www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-41488081.

Briggs, William. How America Got Its Guns : A History of the Gun Violence Crisis. University of New Mexico Press, 2017. EBSCOhost, https://search-ebscohost-com.libdbmjc.yosemite.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1423319&site=ehost-live.

Christopher S. Koper, and Jeffrey A. Roth. “The Impact of the 1994 Federal Assault Weapon Ban on Gun Violence Outcomes: An Assessment of Multiple Outcome Measures and Some Lessons for Policy Evaluation.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology, vol. 17, no. 1, 2001, pp. 33–74, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007522431219.

Clarke, Kevin, and James Martin. “A History of Violence: Gun Control in America.(VANTAGES Ql NT: 1967-2013).” America (New York, N.Y. : 1909), vol. 215, no. 2, 2016, p. 31–.

Coleman, Arica L. “When the NRA Supported Gun Control.” TIME, 29 July 2016, time.com/4431356/nra-gun-control-history/.

Depew, Briggs. “The Effect of Concealed-Carry and Handgun Restrictions on Gun-Related Deaths: Evidence from the Sullivan Act of 1911.” The Economic Journal, vol. 132, no. 646, August 2022, pp. 2118–2140, doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueac004.

DiMaggio, Charles et al. “Changes in US mass shooting deaths associated with the 1994-2004 federal assault weapons ban: Analysis of open-source data.” The journal of trauma and acute care surgery vol. 86,1 (2019): 11-19. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000002060.

Duwe, Grant, et al. “Forecasting the Severity of Mass Public Shootings in the United States.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology, vol. 38, no. 2, 2021, pp. 385–423, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09499-5.

Eddlem, Thomas R. “The Racist Origin of America’s Gun Control Laws.” The New American (Belmont, Mass.), vol. 30, no. 18, 2014, p. 35–.

Fortgang, Erika. “How They Got the Guns: A Look at How School Shooters Are Getting Weapons So Easily.” Rolling Stone, 10 June 1999, www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/how-they-got-the-guns-175676/.

“Gun Violence Is a Racial Justice Issue.” Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, 2019, www.bradyunited.org/issue/gun-violence-is-a-racial-justice-issue.

Hofstadter, Richard. “America as a Gun Culture.” American Heritage, vol. 21, no. 6, October 1970, www.americanheritage.com/america-gun-culture.

Kopel, David, and Joseph Greenlee. “The Racist Origin of Gun Control Laws.” The Hill, 22 Aug. 2017, thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/civil-rights/347324-the-racist-origin-of-gun-control-laws/.

Krajicek, David J. “How Author's Death Over 100 Years Ago Helped Shape New York's Gun Laws.” New York Daily News, 19 Jan. 2013, www.nydailynews.com/news/justice-story/1911-shooting-led-ny-gun-law-article-1.1240721.

Lopez, German. “How Gun Control Works in America, Compared with 4 Other Rich Countries.” Vox, 14 March 2018, www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2015/12/4/9850572/gun-control-us-japan-switzerland-uk-canada.

Lacombe, Matthew J. “The Political Weaponization of Gun Owners: The National Rifle Association’s Cultivation, Dissemination, and Use of a Group Social Identity.” The Journal of Politics, vol. 81, no. 4, 2019, pp. 1342–56, https://doi.org/10.1086/704329.

Platt, Daniel. “New York Banned Handguns 100 Years Ago ... Will We Ever See that Kind of Gun Control Again?” History News Network, https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/141708.

Silva, Jason R. “Global Mass Shootings: Comparing the United States Against Developed and Developing Countries.” International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 21 March 2022. Taylor & Francis Online, doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2022.2052126.

Spitzer, Robert. “How the NRA Evolved from Backing a 1934 Ban on Machine Guns to Blocking Nearly All Firearm Restrictions Today.” The Conversation, 25 May 2022, theconversation.com/how-the-nra-evolved-from-backing-a-1934-ban-on-machine-guns-to-blocking-nearly-all-firearm-restrictions-today-183880.

Winkler, Adam. “The Secret History of Guns.” The Atlantic, Sep. 2011, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2011/09/the-secret-history-of-guns/308608/.