Circuit Riders, Midnight Appointments, and Packed Benches: A History of the Supreme Court

One ruler by which to measure the success of a given presidency is by its appointment of judges, as these appointments remain long after a president leaves office, allowing a lasting influence on law and public policy. In fact, according to Jay Sekulow of the American Center for Law and Justice, court appointments are “the lasting legacy of the President, for every conceivable issue.” By this benchmark, if you’ll excuse a pun, and perhaps by no others, Trump’s presidency can be considered a success by his party. For reference, over 4 years, he managed to nominate almost 300 federal judges, and got more than 240 confirmed, including three Supreme Court Justices. By comparison, over 8 years, Obama only got about 350 confirmed, including 2 Supreme Court seats. This means Trump was on track to appoint nearly double the number of judges as Obama had. Now, Trump claimed in his recent “debate” with Biden that this is because Obama negligently left him seats to fill. In point of fact, Obama had been obstructed throughout his presidency by Senate Republicans, even when they did not have control of the Senate. You see, there was a longstanding practice of senatorial courtesy that said a federal court nominee for any given state must get approval from both its Senators, which Republicans consistently refused to give. In 2013, Majority Leader Harry Reid exercised a “nuclear option” to circumvent their obstruction, limiting confirmation debate and requiring only a simple majority to confirm, which resulted in Obama’s judge confirmation rate soaring to 90%. However, Republicans took the Senate in 2014, and new Majority Leader Mitch McConnell took their obstruction to unheard of levels, reducing Obama’s confirmation rate to a dismal 28% over the next two years. This was why so many seats remained to be filled when Trump took office, and McConnell, already leveraging the Democrats’ own nuclear option against them, introduced a few tricks of his own: he extended the practice of requiring only a simple majority even to Supreme Court nominations, which Reid had excluded, AND he declared that they would not observe Senatorial courtesy, meaning essentially they would ignore a blue slip from a Senator objecting to a nominee in his or her state, a completely hypocritical flip flop from when he insisted that Republicans could use blue slips to veto any nominees. This paved the way for Trump to get judges confirmed far more easily than his Democratic predecessor. But I suppose, if we’re looking for who to credit or blame for the Trump administration’s appointment of a quarter of all active federal judges within 4 years, it seems more like McConnell’s legacy than Trump’s.

But here’s the thing. Judges are meant to be non-partisan. Of course, all people have political leanings, but judges are expected not to let their partisanship influence their interpretation of law. Therefore, clearly ideological nominees have always been controversial and even damaging to a President, especially when they are nominations to the Supreme Court of the United States. In 2009, when Obama nominated Sonia Sotomayor, Republicans objected that she was a liberal judicial activist, and 31 of them voted nay on her confirmation, but Dems still managed to get her confirmed with a supermajority of 67 votes, surpassing even the 60 votes needed. Then, in 2010, conscious of the Senate fight that might result from a controversial nominee, Obama nominated the moderate Elena Kagan and was criticized by his own party for it, since she would be replacing John Paul Stevens, who was considered by many the most liberal leaning justice on the bench. But despite this concession of nominating a moderate even while his party held the majority and he could have gotten a liberal-leaning justice confirmed, he faced an uphill battle with Senate Republicans, who seemed determined to object to any nominee, resulting in an even more hard-won confirmation with only 63 yea votes for Kagan. Come March 2016, a full 8 months before the election of a new president and ten months before the end of Obama’s final term, sitting conservative Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia passed away unexpectedly of natural causes in his sleep. Trying to avoid another controversy, Obama nominated another moderate, Merrick Garland. This time, McConnell had a firm stranglehold on the Senate, and he made the scandalous decision to simply ignore the nomination and not convene a confirmation hearing at all. He cited history to defend his decision, claiming that no Senate has confirmed a nominee from a President of an opposing party during the last year of their presidency since the 1880s. It’s unclear what example of such a confirmation he’s referring to in the 1880s, but it is clear that he was not telling the truth. In 1988, during the last year of Reagan’s presidency, a Democrat-controlled Senate confirmed Anthony Kennedy 97 to 0. McConnell might object that Dems confirmed Kennedy because the moderate Kennedy was a concession, but so was the moderate Merrick Garland. And here’s the thing, if we want to find an actual historical precedent for the obstruction of McConnell and his Republican Senate, we have to look much further back than the 1880s. You see, no Senate has simply refused to hold a confirmation hearing for this reason since 1853! Back then, when political parties held no resemblance to our party system today, Whig president Millard Fillmore nominated Edward Bradford in August of 1852, an election year, and the Senate, controlled by the opposing party, did nothing. Then, as a lame duck, Fillmore made two more nominations, George Badger and William Micou, and the Senate majority continued to do nothing, waiting it out until the inauguration of the new president, one of their own, so that they could give him the seat to fill. And if one is not troubled by the hypocrisy of McConnell’s justification for his inaction—claiming falsely that such a thing hadn’t been done since the 1880s when in fact what HE was doing hadn’t been done since the 1850s—then certainly one should be appalled at his subsequent flip-flop in 2020, when just days before an election his party’s president was polling to lose—and of course did, unequivocally, lose—he rammed through a conservative nominee to the Supreme Court to fill the seat of the recently passed liberal justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, against her dying wishes, just a week before election day. Since these events, there has been much talk among progressives of a need to expand the Supreme Court, which liberals may characterize as a balancing of the bench, and conservatives denounce as packing the bench. So it’s time to look to the history of the Supreme Court and its structure to determine what precedent there may be for its expansion and to evaluate what the case may be for doing it beyond partisan one-upsmanship.

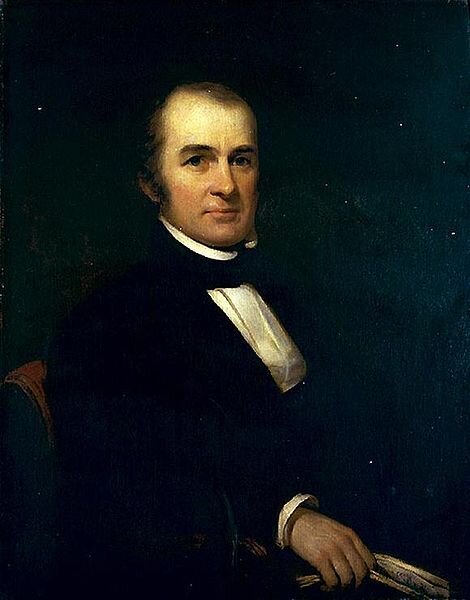

George Badger, a Supreme Court nominee denied a confirmation hearing like Merrick Garland way back in 1853. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In discussing the controversy over McConnell’s underhanded tactics to take a conservative majority of Supreme Court seats and the controversy over the prospect of a Democratic Congress expanding the court, we must first establish a baseline understanding of the formation of the Supreme Court, how its structure has changed throughout American history and why, as well as how those changes were effected. Recently, with some Democrats discussing their openness to judicial reforms like expanding the Supreme Court bench or establishing term limits for its justices, Marco Rubio, a Republican Senator from Florida, has proposed a Constitutional amendment to prevent more than nine seats from being added to the Supreme Court bench, which Rubio says would be “delegitimizing" and suggests would represent a “further destabilization of essential institutions,” though of course he doesn’t indicate how this would delegitimate or destabilize the highest court in the land. In fact, he himself admits that “[t]here is nothing magical about the number nine. It is not inherently right just because the number of seats on the Supreme Court remains unchanged since 1869.” So it seems apparent that by delegitimize and destabilize he only means that he wants to prevent the opposing party from offsetting of the ill-gotten majority that conservatives have seized… so really he wants to prevent it from being stabilized. But regardless, getting an amendment passed is unlikely, since it would require a supermajority vote in both houses OR two-thirds of states legislatures to approve—I think I said it requires both in my last post, but it’s either/or, and regardless, it’s unlikely to happen. But this just highlights the fact that the number of seats on the Supreme Court is not written into our Constitution. In fact, the Framers of the Constitution had little to say about the structure of the Supreme Court, preferring to leave that to the first Congress, who in the Judiciary Act of 1789 established three circuits and a Supreme Court of six justices who would preside over the circuits. Even then, though, Senators argued for more than six justices, suggesting that a deeper bench of justices would lend the court dignity, like England’s Exchequer chamber, and that having more critical minds at work would make for better considered verdicts. In the end, though, they settled on the six, reasoning that, as the country’s population grew, they could always add more. Since then, seven more times, by the passage or repeal of Judiciary Acts, it has fluctuated between 5 and 10 seats. So all it takes, all it has ever taken, is an act of Congress to add seats to the Supreme Court. What Rubio wants to do with an amendment is take away the ability of Congress to pass Judiciary Acts to alter the structure of the Supreme Court, which itself would be a “further destabilization of essential institutions.” But the question to be considered now is, what was the reasoning, historically, behind changes to the structure of the Supreme Court, and how does it reflect on the case for expanding the Supreme Court today?

The first of these changes to the structure of the Supreme Court came just after the contentious election of 1800, about which I spoke so much in my episode on Illuminati conspiracy theories in America, and the Judiciary Act of 1801 was extremely controversial then and even today. The act, passed by lame duck Federalists after their party’s power had essentially been obliterated with John Adams’s defeat in the recent election, was portrayed by Thomas Jefferson as a last ditch effort by Federalists to entrench their power institutionally in the judicial branch of government. It looked suspicious that it had been passed with such haste less than a month before Jefferson’s inauguration, creating with the stroke of a pen several new circuit courts and with them, more than 20 new judge seats, 18 of which Adams managed to fill with so-called “midnight appointments” made between February 20th and March 4th, literally the day before Jefferson took office. And not only did this act dramatically expand the federal court system and pack it with Federalists, it also made it more difficult for Jefferson to put any man of his own on the Supreme Court by establishing that, at the time of the next vacancy, the court would simply be reduced by one seat, bringing it from six to five justices. Adams refused to attend Jefferson’s inauguration, where Jefferson actually made a conciliatory plea to his opponents for national unity. Upon taking office, he found some of these midnight commissions signed and undelivered, and he refused to deliver them, instead appointing men of his own to some of these judgeships. Not only that, he immediately set about working with his party to repeal the Judiciary Act of 1801, which he succeeded in doing, reversing the expansion of the federal circuit courts and restoring the size of the Supreme Court. A few years later, when Federalist Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase publicly expressed his dissatisfaction with the act’s repeal, Jefferson called his remarks “seditious” and encouraged the House of Representatives to impeach him, which they did. This was the first and only time a sitting Supreme Court Justice was impeached.

Tiebout, Cornelius, Engraver, and Rembrandt Peale. Thomas Jefferson, President of the United States. [Philada. Philadelphia: Published by A. Day, No. 38 Chesnut Street, Philada., ?] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/96522974/>.

For about a century, historians gobbled up Jefferson’s version of the Midnight Judges Act, vilifying Adams for abusing his power to embed Federalism in the courts, but in the 20th century, this view of the act has been questioned. In point of fact, the act had been written before the Federalists lost their power in the election, and all of its provisions were enacted to address the real concerns of Supreme Court Justices. The way the court system had been established in 1789, the Supreme Court was the highest appellate court, but some of its justices were also required to sit as trial judges in the circuit courts. This meant that justices had to “ride the circuit,” or travel sometimes great distances in inclement weather in order to judge cases in the various circuit courts, and it also meant that, when some of the same cases they had presided over on the circuit were appealed, they were appealing to the same judge who had already decided the case. While it was believed that Supreme Court Justices would become better judges by being out there, sitting in courtrooms all across the country, justices complained that the burden of constant travel prevented them from cultivating their knowledge of the law through study—basically time they spent on the road, they said, would be better spent in a library—and the fact that the process frequently resulted in them reviewing their own decisions shows it was poorly thought out. In practice, circuit courts often could not even be convened because the Supreme Court Justice who was supposed to preside did not show up. So, although the making of midnight appointments placing mostly his own loyal Federalists into judgeships remains questionable, the Judiciary Act of 1801 can be seen as a clear attempt to address these problems by creating the office of the circuit court judge, and since Supreme Court Justices would no longer need to ride the circuit, it stood to reason they also would not need so many justices. Thus the reduction in seats. Perhaps the most important lesson to take from this episode, however, can be found in a petition to Congress by the Supreme Court in 1792, asking for Congress to fix the court. In their appeal, they referred to the “general and well-founded opinion” that the Judiciary Act of 1789 that had created the court “was to be considered as introducing a temporary expedient rather than a permanent system and that it would be revised….” Here the first Supreme Court Justices themselves indicate that the structure of the Supreme Court was not set in stone at its creation. Rather, it was meant to be an evolving institution, changing with the needs of the country.

At first, the court expanded specifically because of the growth of the country. After the repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801, justices were once again required to ride the circuit, but as new circuit courts were added, so also were new Supreme Court Justices to ease the burden. With the Seventh Circuit Act of 1807, another circuit was added and thus another Supreme Court justice. Then during Andrew Jackson’s administration, the Eighth and Ninth Circuits Act of 1837 added a couple more, bringing the number of justices to nine. If we had continued to keep the number of seats on the bench proportional to the number of regional circuits, then we would have 12 or 13 justices now, but this did not remain the basis for the Supreme Court’s structure. A 10th Circuit and thus a 10th justice were added briefly during the Civil War, but in 1866, the Judicial Circuits Act reduced the number of circuits to nine and the number of Supreme Court seats to seven. This act was really a redistricting effort to minimize the influence of Southern slaveholding states, which because of the way circuits had been drawn had previously dominated the Supreme Court. Finally, in 1869, another Judiciary Act set the number of justices at nine and once more created circuit court judges who would sit with district court judges to hear appeals, thus greatly reducing the burden placed on Supreme Court justices of having to ride the circuit. One would think that, after this, all was well. Thus divorced from the circuit courts, nine justices should have been plenty to hear whatever higher appeal cases arose, especially since only 6 of those justices were needed to form a quorum, the minimum number assembled to be considered valid. But the country was growing still, and so was the court’s workload. By the late 19th century, with around 600 new cases being filed a year, they were running a backlog of nearly 2 thousand cases! Once again, the Court appealed to Congress, and many believed then that the Supreme Court should be expanded to eleven or even eighteen justices in order to handle their case load. One Senator Manning even proposed that it be expanded to 21 justices composed of three panels of seven justices each! In the end, though, instead of expanding the bench, Congress chose to reduce the case load first, in the Judiciary Act of 1891, by creating a court of appeals for every circuit, and then, in 1916, by giving the Supreme Court the right to decline to review cases. So rather than increase the ability of the highest court to take on more cases, they enabled it to simply refuse to consider cases. So the Supreme Court went from hearing arguments on nearly 100% of the cases brought before it to considering only around 1% of petitions.

FDR delivering a “fireside chat.” Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Then came the Great Depression and Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation, intended to aid in the country’s recovery. FDR could not contain his disappointment and reproval when the Supreme Court handed down a series of decisions in 1935 and ’36 that vitiated some key centerpieces of the New Deal, such as the Railroad Retirement Act, the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the National Industrial Recovery Act, and a minimum wage law for women and children. In one of his signature Fireside Chats in March of 1937, he characterized the court as working at counter purposes with the rest of the government. To FDR, the refusal of older justices to retire was something that had not been foreseen by those who had crafted the structure of the court, allowing a bench dominated by individuals who were out of touch with the current needs of the country and the political will of the people. He proposed the automatic addition of a younger justice whenever a sitting justice reached 70 and refused to retire. This proposal was dubbed “court packing,” a term you may have heard recently with the resurgent talk of expanding the bench. If such a policy were enacted through legislation today, it would automatically result in the addition of three new justices, one each for Stephen Breyer, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito, all of whom are 70 or older. The total number of justices would rise to 12 until some older justices retired. And if Sonia Sotomayor and John Roberts, both of whom are nearing seventy, didn’t retire in a few years, that number could climb higher. But no Democrats have specifically proposed FDR’s plan. Nevertheless, opponents of expanding the court still summon memories of this controversial proposal by calling any judicial reform “court packing.”

As a bit of an aside, I recently received a critical email from a listener suggesting that I have a case of historical blindness because in my last episode I referred to the current Supreme Court as “packed” and “conservative-packed,” after asserting that Trump had packed it with conservative justices. He, like some in that media, would accuse me of purposely misusing the term, and of projection, since in his view, I am saying conservatives are guilty of packing the court, when liberals are the one advocating “court packing” in the 1930’s sense of the term. First, I’ll say that I would never claim to be immune from historical blindness. I have many times during the course of making this podcast exploded myths that I myself have previously held as true or even mentioned on the show! Case in point: the midwife-witch and folk healer-as-witch myths that I believe I ignorantly spread before discovering they were dubious this October. However, in this case, I don’t believe that the word “packing” is or even historically was used only to refer to Supreme Court expansion. Who can forget the ribald jokes about “Bush packing” when George W. Bush was being accused of packing the courts. Indeed, if you look to the useful Google NGram tool, it’s rather easy to see how early the term was being used. While the specific phrase “court packing” does indeed first peak in the literature of 1937, the phrases “packed bench” and “packed court” (the latter of which was the term I used) were in fact far more commonly used in the 19th century. The terms “packed court” or “packed bench” were invariably used to refer to courts in which the judges were prejudiced, among whom a certain ideology dominated, coloring their decisions. An apt example of this usage can be found in the remarks of Ohio Representative Benjamin Wade regarding the Supreme Court decision on the Dred Scott case, when he called the justices “packed judges—for they were packed, and I have about as little respect for a packed court as I have for a packed jury.” To clarify, Wade was alleging a conflict of interest, a prejudice or bias, stating, “I believe, the majority who concurred in the opinion were all slaveholders, and, of course, if anybody was interested to give a favorable construction to the holders of that species of property, these men were interested in the question.” So, as it turns out, I would venture to assert that my usage of the term “packed court” as referring to a bench of justices dominated by ideologues was correct. Of course, that is a case that I’ll have to make, and I’ll attempt to do so, momentarily.

The Supreme Court bench that Benjamin Wade called “packed,” via supremecourthistory.org

FDR’s “court packing” proposal ended up fizzling out when the Supreme Court started reversing decisions and finding in favor of New Deal legislation. Some have portrayed this as the Supreme Court beating FDR at his own game, causing him to lose support for “court packing” because there was no longer a need for it. However, another view is that he put political pressure on the court and got what he wanted. A historical debate has since raged over whether or not the justices of the Supreme Court at the time were actually swayed by FDR’s pressure or whether they would have ended up coming to their favorable decisions regardless. This debate, between “externalists” arguing that external pressure made the difference, and “internalists” who assert that the justices did not allow themselves to be influenced by partisan politics, really gets at the heart of the debate surrounding both the Supreme Court’s partisanship and its role among the tripartite branches of government. One common view is that regardless of the personal views of the justices, the Supreme Court is inevitably a majoritarian force, if not bowing to the will of the party in power then at least leaning in the direction the wind seems to blow, which is sometimes in the direction of cross-partisan coalitions. The idea here is that the court must play politics to a certain degree and cannot make decisions that are unpopular with the majority or they may be viewed as illegitimate and risk congressional intervention. This view works well with the externalist idea that FDR made them reverse their decisions by appealing to the people and painting them as obstructive to the national recovery. Then there is the view that the Supreme Court justices truly are uninfluenced by politics, a perspective that somehow raises them up as superior to most people in their ability to disregard such matters, a view encouraged by the “internalist” interpretation of this so-called Constitutional Revolution of 1937. But then there is the view that the Supreme Court is a counter-majoritarian force, in that, through its power of judicial review, it can strike down legislation passed by the representatives elected by the people, and thus acts as a check on not just other branches of government but on the will of the majority. Although historians of the court consider this latter view of its role something of a myth, Roosevelt certainly seems to have held it, at least until the court turned his way. But what about today? Can this Supreme Court be considered a “packed court” dominated by partisan activists poised to act counter to the will of the people?

If we are looking for proof of a concerted effort to pack the bench of the Supreme Court and federal courts generally with justices who will take a conservative view in all their decisions, we need look no further than the Federalist Society. You may have heard of this organization before, but now, after my discussion of Adams’s midnight appointments, you know that their name could easily be interpreted as a reference to the original court-packers, the Federalists. Starting out during the Reagan Era as a group of conservative and libertarian law students mentored by Antonin Scalia, they bemoaned the atmosphere of liberal academia and advocated for a more originalist view of the Constitution. Since then, the organization has grown by leaps and bounds, mainly due to a vast influx of funding from donors with deep pockets, so that now it boasts several tens of thousands of members, law professors, politicians, pundits, and judges. In fact, many in the field see the Federalist Society as their best shot at securing a judgeship, because the organization has established itself as the go-to for any Republican President, providing a short-list of candidates who conform ideologically with their conservative principles. So you have lawyers and judges toeing this ideological line, kowtowing to the Federalist Society and their rubric in order to secure a better chance of advancement. At this point, the majority of the Supreme Court bench attained their lifetime appointments by meeting this de facto conservative requirement of membership in the Federalist Society: Chief Justice John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and now Amy Coney Barrett, who seems to have been groomed by the society to take her seat on this packed bench. An enlightened centrist might argue that both sides are guilty of such judge grooming, but in fact, the frequently cited liberal counterpart to the Federalist Society, the American Constitution Society, was only formed in 2001 when the growing influence of the Federalist Society became clear after the Supreme Court handed George W. Bush the presidency. The ACS, however, is still in its infancy, without the deep funding and membership that the Federalist Society enjoys.

Now, it may be hard to imagine anyone these days being wide- and dewy-eyed enough to argue that the Supreme Court really is the non-partisan institution that idealists would like it to be. But the mere fact that the Supreme Court bench is and always has been a partisan battleground doesn’t mean that taking back a majority for the other side is enough of a justification for expanding the court. In fact, such an argument should rightly be viewed as squalid and distasteful. Actually, I don’t shrink from suggesting that the ruthless tactics employed by conservatives like Mitch McConnell and the Federalist Society to take their majority might call for equally obdurate countermeasures, and that “balancing” the court would not be an unfair characterization of such measures. However, there is a far more virtuous case to be made for the expansion of the Supreme Court. Beyond a possibly pressing need to thwart a counter-majoritarian power grab, there is the fact, as made evident throughout this history of the Supreme Court, that having a deeper bench would allow the highest appeals court in the country to take on far more cases than it currently deigns to hear. More decisions would result in more consistency and clarity in American jurisprudence. More cases means more chances for judicial review and interpretation, which makes the Supreme Court a far more effective check on the executive and legislative branches of government as well. And more justices, able to rotate and interchange in differently structured quorums, would vastly reduce the influence of swing votes. Right now, just as swing states decide presidential elections, swing justices decide most important interpretations of the Constitution. Reducing the disproportionate power of the swing justice will then in turn reduce partisan activism on the court, or at least it will diminish the perception of its politicization. And that is just what the U.S. needs right now, to turn down the country’s partisanship generally. This might be a hot button partisan issue, but it represents a path to a little less division.

Further Reading

Bomboy, Scott. “Packing the Supreme Court Explained.” Constitution Daily, 20 March 2019, constitutioncenter.org/blog/packing-the-supreme-court-explained.

Bridge, Dave. “The Supreme Court, Factions, and the Counter-Majoritarian Difficulty.” Polity, vol. 47, no. 4, 2015, pp. 420–460. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24540303.

Carney, Jordain. “Rubio to introduce legislation to keep Supreme Court at 9 seats.” The Hill, Capitol Hill Publishing, 20 March 2019, thehill.com/homenews/senate/434888-rubio-to-introduce-legislation-to-keep-supreme-court-at-nine-seats.

Carpenter, William S. “Repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801.” The American Political Science Review, vol. 9, no. 3, 1915, pp. 519–528. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1946064.

Farrand, Max. “The Judiciary Act of 1801.” The American Historical Review, vol. 5, no. 4, 1900, pp. 682–686. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1832774.

Gramlich, John. “How Trump compares with other recent presidents in appointing federal judges.” Pew Research Center, 15 July 2020, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/15/how-trump-compares-with-other-recent-presidents-in-appointing-federal-judges/.

Greenberg, Jon. “Fact-check: Why Barack Obama failed to fill over 100 judgeships.” Politifact, Poynter Institute, 2 Oct. 2020, www.politifact.com/factchecks/2020/oct/02/donald-trump/fact-check-why-barack-obama-failed-fill-over-100-j/.

Kalman, Laura. “The Constitution, the Supreme Court, and the New Deal.” The American Historical Review, vol. 110, no. 4, 2005, pp. 1052–1080. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/ahr.110.4.1052.

Kruse, Michael. “The Weekend at Yale That Changed American Politics.” Politico Magazine, Sep/Oct. 2018, www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/08/27/federalist-society-yale-history-conservative-law-court-219608.

Madonna, Anthony J., et al. “Confirmation Wars, Legislative Time, and Collateral Damage: The Impact of Supreme Court Nominations on Presidential Success in the U.S. Senate.” Political Research Quarterly, vol. 69, no. 4, 2016, pp. 746–759. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44018054.

Mandery, Evan. “Why There’s No Liberal Federalist Society.” Politico Magazine, 23 Jan. 2019, www.politico.com/magazine/story/2019/01/23/why-theres-no-liberal-federalist-society-224033.

Matthews, Dylan. “The incredible influence of the Federalist Society, explained.” Vox, 3 June 2019, www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/6/3/18632438/federalist-society-leonard-leo-brett-kavanaugh.

Robinson, Nick. “Structure Matters: The Impact of Court Structure on the Indian and U.S. Supreme Courts.” The American Journal of Comparative Law, vol. 61, no. 1, 2013, pp. 173–208. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41721718.

Surrency, Erwin C. “The Judiciary Act of 1801.” The American Journal of Legal History, vol. 2, no. 1, 1958, pp. 53–65. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/844302.

“What Is The Federalist Society And How Does It Affect Supreme Court Picks?” NPR, 28 June 2018, www.npr.org/2018/06/28/624416666/what-is-the-federalist-society-and-how-does-it-affect-supreme-court-picks

Williams, Joseph P. “McConnell to End Senate’s ‘Blue Slip’ Tradition.” U.S. News & World Report, 11 Oct. 2017, https://www.usnews.com/news/politics/articles/2017-10-11/mcconnell-to-end-senates-blue-slip-tradition.

![Tiebout, Cornelius, Engraver, and Rembrandt Peale. Thomas Jefferson, President of the United States. [Philada. Philadelphia: Published by A. Day, No. 38 Chesnut Street, Philada., ?] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57d0686e6b8f5b98e0543620/1606717713969-QJ3XT1V293D6G6K63459/image-asset.jpeg)