Before Columbus - Part One: First Contact

Though schoolchildren used to be taught that Christopher Columbus had to convince the Catholic Monarchs of Spain that the Earth is actually round and not flat, and thus could be circumnavigated by a westward voyage across the Atlantic, we know this to be a myth. In fact, it had been known since antiquity that the Earth is spherical and that it was theoretically possible to sail west to reach the east. However, Columbus did indeed have his work cut out for him to convince the monarchs to finance his voyages, for it remained to be understood how long such a voyage might take and whether or not there may be some islands or continents blocking his path. Certainly there were legends of islands out there, the phantom and mythical islands of Antillia, Hy-Brasil, St. Brendan’s Island, and Frisland. Some suggest that Columbus had actually gathered intelligence about the lands beyond the seas before pitching his voyages to European monarchs. According to Bartolomé de las Casas, Columbus had firsthand knowledge of these lands, having sailed to the equally mythical northern land of Ultima Thule in 1477, which voyage some have argued took him past Greenland to somewhere on the North American coast near where the Norse had established their Vinland colony. In truth, the only record of this supposed early voyage of Columbus’s is a marginal note by de las Casas, which may have referred to a trip to Greenland or Iceland and may never have even occurred. Further rumor had it that Columbus learned of this route to the Americas from a Bristol sailor, and that the English had established a trade route to these new lands, a claim that the Spanish would not have liked to acknowledge, and which historians also refute. After Columbus’s contact with the “New World,” Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo would argued that, actually, he hadn’t really discovered anything that wasn’t already known. Oviedo’s account of Columbus’s voyages begins with the statement, “Some say that these lands were first known many centuries ago, and that their situation was written down and the exact latitudes noted in which they lay, but their geography and the sea routes by which they were to be reached were forgotten.” He then goes on to mention a rumor that would conveniently establish Spanish claim to the New World—the story that a Spanish caravel had been overwhelmed by winds and sent off course, eventually landing in the West Indies, where its crew made contact with native islanders. According to this legend, only a handful of the crew survived their arduous return to Europe, and even these were so sick that they passed away shortly after their arrival at Portugal. As the legend claims, Columbus knew or met the surviving pilot of this ill-fated voyage, collected information from him at his deathbed, and created a map that he used to find the Caribbean. De Oviedo seems to mention the tale only to qualify the claims about Columbus’s achievements, though he remarks himself on the extreme variation in the legend’s details and declares that it is probably a fiction. Many are the legends of Pre-Columbian Trans-Oceanic Contact like this. Some, as we have seen with the stories of medieval Scandinavian contact with the Americas, are upheld by evidence that supports their truth, even if they are also confounded by hoaxes and unreliable claims. But others lack such confirmatory support and should be questioned. As de Oviedo himself explained, “It is better to doubt what we do not know than to insist on facts that are not proven.”

Any who are new to my content and unfamiliar with the topics I’ve covered in the past may find it informative to learn here, at the outset, that the topic of Pre-Colombian Trans-Oceanic Contact Theories has long fascinated me. I have covered such theories in passing or in part in a variety of episodes, including briefly in my episode on the Myth and Mystery of Columbus. Obviously just in the last episode I explored Norse contact with the Americas, which has been confirmed archaeologically in Newfoundland, while disputing claims of contact further inland, as supported by the Midwestern Runestones that evidence leads us to dismiss as hoaxes. Before that, in a series I highly recommend you check out between parts one and two of this series if you haven’t heard it already, I talk about the claims of the Hebraic origins of Native Americans in my series on the Lost Tribes of Israel, a series that led me to focus even more on the hoax artifacts that support such claims in an episode on The Archaeological Frauds of Pre-Columbian Trans-Oceanic Contact Theories. Perhaps the wildest of these theories that I’ve looked at, in an episode that I find continues to get a lot of downloads, is the conspiracy fantasy about a lost globe-spanning empire built by giants called Tartaria, which if you can believe it, claims that a lot of buildings with classical architecture right here in the U.S. are actually ancient remnants of a super-civilization, and this true history of the world is being erased by “elites.” Most of these can be confidently dismissed even with cursory analysis of their lack of evidence and, especially in the case of the Tartarian Empire nonsense, their ludicrous and ignorant assertions. However, even despite the hoaxes of the Midwestern Runestones, the fact that a medieval Norse presence has been proven beyond doubt in Newfoundland goes to show that not all of these theories can be confidently dismissed. The history of the Americas can only be pieced together through archaeological remains and other interdisciplinary approaches, as we will see, precisely because we lack a robust historical record from American antiquity. This is not only because few indigenous cultures developed their own writing systems, but also because, among those that did, the Spanish systematically burned all their written records. “Burn them all,” Diego de Landa, 16th-century Bishop of Yucatán, is quoted as saying, with the rationale that, “they are the works of the devil.” As the discovery at L’Anse aux Meadows proved, though, theories of Pre-Columbian trans-Atlantic contact can be confirmed even in the absence of any extensive indigenous historical record. And why could not some accidental traffic have occurred between the continents, such as the Spanish caravel said to have drifted to the New World, when the circular currents of the Atlantic are known to carry ships off-course and across the ocean. We must search for evidence of both purposeful and accidental crossings to determine what trans-oceanic contact may have preceded Columbus, and since we know from the Newfoundland find that Vinland, which I might point out was found accidentally according to the Saga of the Greenlanders, was no myth, then perhaps we should look at the claims of earlier crossings to determine first contact, as a Trekkie might call it.

Diego de Landa, Franciscan inquisitor notorious for burning Mayan codices.

Among the most popular of first contact theories out there is the argument that the first seafaring people to cross the Atlantic and encounter the indigenous peoples of the Americas came not from Europe at all, but rather from Africa. Indeed rumors of an African crossing go all the way back to Columbus’s time, again, according to Bartolomé de las Casas, who wrote that Columbus’s third voyage was actually undertaken to investigate a rumor heard by King John II of Portugal that the West Africans from Guinea were crossing the Atlantic in canoes and had established trade with the inhabitants of the New World. On this same voyage, de las Casas says that Columbus took interest in the claims of natives on the island he called Española, or Hispaniola, where today can be found the countries of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, that “a black people” had come to them “from the south and south-east.” Much has been made of this line, though it seems most likely that Columbus was interested in the rumor not because he believed West Africans had visited the Caribbean but rather because he had been told by the Majorcan explorer Jaume Ferrer that “gold was found most abundantly near the equator where people had dark skins and where the spin of the earth caused it to collect.” De las Casas would not have been the first to have used the term “black” to describe the color of darker skinned Native Americans, as a variety of other Spanish explorers, historians, and clergymen have written about seeing black-skinned natives in the Americas. Just how they differentiated and categorized the variety of skin colors they observed in the New World is unclear, and indeed, there may be an error in translation, as well, since the Spanish word for “black” can also be used to simply mean “dark.” These uncertain beginnings of the theory of African contact with the Americas, however, would expand when, in the mid-19th century, a massive carved stone head believed to have originated from the Olmec culture, an ancient precursor civilization to other Mesoamerican cultures like the Maya and Aztec peoples, was unearthed in Mexico and deemed by many to physically resemble Black African facial features. Thus began more in-depth research and the development of the theory of African Pre-Colombian Trans-Oceanic Contact by researchers such as Leo Wiener in the 1920s, with his work, Africa and the Discovery of America. Others followed, but the most recognized and influential of these theorists today is Ivan Van Sertima, whose 1976 work, They Came Before Columbus: The African Presence in Ancient America would take this otherwise fringe academic hypothesis into the mainstream, where it would be championed by Afrocentric critics who criticize Eurocentric academia for distorting and marginalizing the historical contributions of Africans to the world.

Afrocentric critics in many cases make a strong and admirable case about the myopia of academia and the legitimate existence of institutional racism and bias that permeates many disciplines, not only that of history and archaeology. Unfortunately, valid and important arguments such as these are sometimes undermined by the influence of hyperdiffusionist claims. Hyperdiffusionism is the pseudoarchaeological tendency to draw parallels between vastly different cultures and claim, without the necessary evidence to support the theory, that those cultures must therefore have originated from some common precursor culture. Whenever someone says that the construction of certain monuments in two disparate cultures must mean that there had been contact between those cultures, denying the possibility of parallel thinking and independent development, there may be a hyperdiffusionist argument being deployed. One of their most common arguments is that pyramids in both Egypt and the Americas shows that both cultures were related to some progenitor civilization, and often they will resort to unfounded claims about Atlantis or Lemuria. Since one of Van Sertima’s principle argument is that Mesoamerican step pyramids indicate some ancient influence by Egyptians, it seems fair to criticize his work as hyperdiffusionist. And when we examine the broad strokes of his theory further, the hyperdiffusionist rhetoric becomes even clearer. Van Sertima essentially claims that Egyptians, more specifically Black Egyptians, or the Nubians of southern Egypt and northern Sudan, whose dynasties preceded the first Egyptian dynasty, and who conquered Egypt again in the 8th century BCE to establish the 25th Egyptian dynasty, crossed the Atlantic and greatly influenced the Olmec, the “mother culture” that preceded the Maya, in Mexico and Guatemala, as evidenced by not only the Olmec colossal heads but also the Mesoamerican step pyramids. He also claims that Mandingo sailors from Mali returned to the New World in the 14th century, led by their very emperor, Abu-Bakari II, and that between the Egyptian and Malian transfusions of knowledge, much of the technological and cultural development of indigenous New World civilizations could be attributed to the influence of African explorers. One of the most cutting criticisms of Van Sertima’s hypothesis is that it negates the cultural identity of indigenous peoples, instead attributing their accomplishments to other cultures, much like the Myth of a Lost Mound-Builder Race, which I examined at length in what I consider a banner episode. Van Sertima and his proponents take great umbrage with this characterization, of course, pointing out passages in his work in which he explicitly rejects such views, asserting that his research “in no way presupposes the lack of native originality.” However, one cannot read his research without tallying the great many aspects of Mesoamerican native cultures that he attributes to outside influence. Indeed, he literally engages in a version of the Mound-Builder Myth when he asserts that the Olmec burial mounds of La Venta are proof of Egyptian influence. So despite Van Sertima’s insistence that he is not guilty of such cultural erasure, as his staunchest critics have pointed out, those who read his work are “left with the impression that all or most of the complex societies in the Americas were created or in some way influenced by African[s]…, and that Native Americans were incapable of creating any civilization or complex societies of their own.”

An Olmec colossal head.

Van Sertima’s critics do not only take issue with the “impression” his work gives, though. They also have serious concerns about his work’s scholarship, for the evidence he relies on is in several ways unreliable. First and foremost is the likeness of the carved Olmec heads to what Van Sertima and others consider to be typical Black African features. Van Sertima’s critics point out that this evaluation relies on racial stereotypes, and that indeed, the features identified, having to do with lip and nose shape, are commonly found in a variety of other peoples as well, including indigenous Americans. Moreover, if we were to read into the features of these works of art, we might be led alternatively to believe that they depict an East Asian figure, due to the apparent presence of an epicanthic fold on the upper eyelid. Indeed, as we shall see, a perceived likeness to Asians has also led to the Olmec heads being cited as evidence of ancient East Asian contact with the Americas. And as for his most popular “evidence,” about the presence of pyramids in the Americas, there are timeline problems with his claims. Van Sertima argues that Egyptians transmitted their practice of pyramid building to Mesoamerican cultures after 1200 BCE, when Egyptians of this period had not built large scale pyramids for more than 500 years. This issue with chronology troubles much of his research, as he makes claims linking aspects of distant Mesoamerican cultures, thousands of years apart, and does not attempt to or cannot demonstrate how they were transmitted from one place to another or why they were not present in the intervening centuries. Similarly, he claims that Egyptians taught the Olmec the technique of mummification, and that this was passed to the Maya, citing as evidence the sarcophagus of the Mayan king Pacal. However, Pacal was not mummified, and there are no such Olmec mummies or sarcophagi, and thus no evidence of the transmission of such a practice between the cultures.

But Van Sertima’s argument does not rest solely on the colossal heads and pyramids. He also marshals botanical and linguistic evidence, yet errors litter his work in these areas as well. Though the reading public who devour sensational historical revisionist books like these—the Graham Hancock readership, if you will—are thoroughly overawed, experts are not, and they have the knowledge to recognize where such authors are pulling one over on readers. One of Van Sertima’s principal botanical proofs is that purple dye was used in the Americas, and that the process for making it could only have been brought here by Egyptians, who used purple ritually in royal garments. However, despite his assertions, it has been proven that purple dyes were created in an entirely different way in the Pre-Colombian Americas, and there is no evidence that the Olmec attached the same cultural meaning to the color. And as with his claims about the practices of pyramid-building and mummification, he provides no evidence that such practices were transmitted between Mesoamerican cultures over thousands of years. The same flaw can be found his linguistic arguments. As we have seen in our examination of many historical myths, they often rely on armchair etymology, and this one is no exception. Van Sertima makes a detailed case that words in Maya and Nahuatl were derived from a variety of African languages, including Arabic, Manding, and Middle Egyptian. However, while the sources he cites to support the claims are other hyperdiffusionists sympathetic to his conclusions, more qualified linguists have pointed out that, not only does Van Sertima fail to provide evidence for the transmission and changing forms of these words through the centuries, as would be typical of a more credible etymological argument, his Nahuatl words sometimes do not even exist or they have an entirely different meaning from what he claims, and even his understanding of Egyptian words is frequently in error.

Pacal’s tombstone at the time of its discovery. Unlike Egyptian sarcophagi, which are carved of wood and person-shaped, we can see that this is more of a standard engraved tomb lid.

Issues of unreliable source material are in fact prevalent in Van Sertima’s work. He tends to rely, as his critics have shown, on outdated and since refuted sources. He does not avail himself of the most recent and most in-depth scholarship or available primary source material, it seems, because it does not serve his preconceptions, and instead he finds support in the work of amateur writers from the 1920s, like the thoroughly discredited Leo Wiener. And he amplifies conspiracy claims as well, such as those surrounding the Piri Reis Map. This map, created by an Ottoman cartographer, features an unidentified coastline across the Atlantic from Africa. The map was compiled in 1513, and it features a representation of the West Indies derived from Christopher Columbus’s voyages, but as the landmass on the left of the map extends downward, and even across the bottom of the page, it has been a lightning rod for conspiracy speculation, with some suggesting it depicts the entire coastline of South America and Antarctica. To give an idea of how this artifact has been misused by fantasists, Erich Von Daniken, the ancient astronauts theorist, has suggested that it must have been drawn by aliens, as he imagines it contains data only plausibly collected from aerial observation. Although not going so far as claiming extraterrestrials made it, Charles Hapgood, a history lecturer at New England colleges in the 1950s and ‘60s who is now remembered for his pseudoscientific claims and out there takes on ancient history, argued that the Piri Reis map must have been drawn not in the 1500s by its known creator but rather in the Ice Age by some advanced civilization. Just to reiterate, he thought it was too accurate and contained too much knowledge of the world for Piri Reis to have made it in the 16th century, so…it must have been made thousands of years earlier, when it’s even less likely that anyone had the knowledge. Of course, Hapgood wasn’t known for his sound theories. He was a catastrophist who promoted the idea of a recent pole shit, claiming that Antarctica had thus been free of ice when the map had been drawn. Today it is recognized that the imaginary coastline Hapgood claimed was South America and Antarctica was more likely Terra Australis, a theoretical southern continent that had been imagined and drawn into maps since the time of Roman geographer Ptolemy, who suspected there just had to be land down there to balance out the landmasses of the known world in the northern hemisphere. Yet when Van Sertima went searching for support for his notion about Egyptian contact with the Americas, it was this crackpot, Hapgood, and his half-baked notions about pole shifts and ancient advanced civilizations that he chose to cite as support. The quality of Van Sertima’s sources alone, then, casts doubt on his reliability as a scholarly researcher and thus on the credibility of his thesis.

Other hyperdiffusionist theories trace the origin of Mesoamerican cultures east of Africa, coming from Asia. Indeed, as already mentioned, the Olmec colossal heads have likewise been used as support for this theory, which unlike Van Sertima’s more developed argument, seems to rest almost entirely on resemblances. For example, Betty Meggers, an archaeologist whose work focused on South America, published numerous articles on her claims that the Olmec culture was actually begun by visitors from Shang dynasty era China. Her argument rests solely on her perception of similarities in art, including, laughably, the presence of jade in both cultures and the frequent depictions of cats in art, as if it is not perfectly natural for two entirely distinct cultures to both think jade was beautiful and to both like cats. She also cites the work of Mike Xu, who claimed to have recognize glyphs on Olmec artifacts as actual Chinese characters, though Olmec language experts view any similarity as coincidental. There was, long before the discovery of the Olmec heads and the discovery of these resemblances, some previous theorizing about ancient Chinese contact with the Americas, owing to a certain tale from Chinese mythology. According to some versions of the tale, there was a tree of life, called Fusang, known to grow far to the east of China. Legend has it that the founder of the Qin dynasty believed the myth to be true and sent one of his men, Xufu, on a voyage to find Fusang, which he believed to be an Island of Immortals, tasking him with bringing back an elixir of immortality. Xufu claimed then to have successfully discovered Fusang, and a few hundred years later, when a missionary named Huì Shēn returned from his travels to tell his emperor tall tales about the lands he had visited, then the idea of Fusang as a strange land was cemented. This Fusang, Isle of Immortals, was sometimes said to be on the Asian Pacific coast, and was even at times identified with Japan, but in some later maps, the term was applied to North America. Though this was not proof of ancient Chinese travel to North America, and likely both Xufu and Huì Shēn were fabulists telling false tales to their emperors, this led, in the 19th century, to a notion that the Chinese had once, long ago, discovered California. And in 1882, during a gold rush in British Columbia, in Western Canada, a string of Chinese gold coins was unearthed, said to have been found 25 feet below the surface in packed earth. Some thought this proof of Chinese contact with the Americas, and the coins drew a great deal of attention. They were, however, eventually exposed as 19th-century charms cast by a Buddhist temple, and one can imagine that they might have been found not 25 feet below ground at all, that this might have been the prank of a gold miner trickster akin to the members of E Clampus Vitus, the Clampers, who loved to claim that their order could be traced all the way back to Chinese explorers who had discovered America. Listen to my episode The Unbelievable History of the Ancient and Honorable E Clampus Vitus, for more on that myth. Suffice it to say, there is little to any of these claims, just as there is even less to the more recent claim, made by former British submarine commander and autodidact Gavin Menzies that Ming dynasty admiral Zheng He discovered America and circumnavigated the globe in 1421, a claim for which, in the two books Menzies wrote on the topic, he failed to provide a shred of evidence.

1792 French world map that falsely identifies Fusang (“Fousang de Chinois”) as being located near British Columbia.

Chinese transoceanic contact was not to be the only such claim made by Betty Meggers and her fellow researchers, though. They have also argued strenuously for the idea that the Japanese made it across the Pacific and influenced native culture in Ecuador. As before, their evidence relied on subjective resemblances in art, specifically in the pottery of the Ecuadorian Valdivia culture, which they reckoned was a bit too similar to pottery produced during the contemporaneous Jōmon period in Japan. Not seeing precedents for such pottery before the Valdivia culture was active, between 4000 and 1500 BCE, but aware that similar pottery could be traced back another 10,000 years in Japan, they reasoned that the ancient Japanese had brought it to the Americas. To refute objections that there was no evidence of seaworthy conveyance at the time that might have made such a voyage possible, she raised evidence of Jōmon period contact between mainland Japan and Kozushima, a certain island about 35 miles offshore, as proof of ancient Japanese navigational capacity. However, 35 miles of open ocean is a lot easier to survive than a crossing of the entire Pacific. Nevertheless, arguments about the feasibility of an accidental drift voyage have encouraged the theory. In 1834, a Japanese merchant ship that had lost its mast and its rudder in a typhoon drifted 5,000 miles to run aground in Washington state. Three of its sailors survived the disaster only to be taken captive by a local Native American tribe. Around 1850, another Japanese ship drifted to the Pacific Northwest, and its survivors too made contact with a local native tribe. In 1890, these incidents led a judge, who just happened to also be involved in violent anti-Chinese mob action, to further research and theorize on the topic. He found numerous incidents of Japanese drift voyages to North America between the 17th and 19th centuries, all carried by the Kuroshio Currents, and concluded that it was not unreasonable to believe that such drift voyages may have been occurring for far longer. The fact of the matter is, though, that even rudderless and dismasted ships from these more modern eras would have been far more seaworthy than the crude ancient watercraft that Betty Meggers believed capable of surviving such a vast distance. And regardless of the feasibility of even a single such accidental voyage first surviving and second making such an impact on American cultures, the more pertinent and harder to answer criticism was that fired clay pottery was simply too rudimentary a technology to claim it could not have been independently invented, and the stylistic elements that she thought resembled Jōmon period pottery were too simple and obvious to be considered derivative… in other words, anyone could have come up with this stuff. Finally, fired clay pottery thousands of years older than that left behind by the Valdivia culture has since been discovered elsewhere, associated with other ancient American cultures, a fact that basically explodes her idea that no one in the Americas could have come up with it on their own.

It is not East Asia alone that has been proposed as one of the cultural contributors to New World civilizations. Additionally, there are some theories regarding contact between South Asia, and specifically India, and the Americas. In 1879, a British Army Engineer noticed in a stupa, which is a place for meditation, a carving dating to 200 BCE that appeared to depict a custard apple, a kind of fruit that originates from the Andes Mountains in South America and wasn’t introduced to India until Vasco de Gama’s arrival. Actually, it is very common for a transoceanic contact theory to arise from a work of art that seems to feature a plant or animal that shouldn’t be known in that part of the world. In the 1920s, a Mayan relief was discovered that seemed, to European eyes, to depict an Asian elephant, further supporting the idea of Indian contact with Mesoamerica, and in 1989, a 12th-century Indian sculpture was seen to feature what looked like an ear of maize, the quintessential New World crop. In fact, though, as further research revealed, what was originally seen as maize was actually Muktaphala, an imaginary fruit covered in pearls known to be depicted in Indian art. As for the Mayan elephant, it turned out to much more likely be a tapir, a rather common animal that, like the elephant, has a prehensile nose trunk. The custard apple, it turned out, is harder to explain away. We might suggest that such artwork was misconstrued, that perhaps it depicted Muktaphala as well, since like maize, the custard apple is a bumpy or noduled fruit. However, archaeologists recently discovered the carbonized remains of custard apple seeds at a dig site in India and dated them to 1520 BCE. This seems to be hard scientific evidence of the custard apple’s presence in ancient India, if not proof of ancient Indian contact with the Americas. If such evidence of transoceanic transmission of fruit were found in the New World, it might be argued that a drift voyage resulting in a shipwreck might have carried the fruit, which may have been found and then proliferated as an invasive species, but the likelihood of currents carrying a drifting vessel from the Americas to India seems near zero. With absolutely no further evidence of transoceanic contact between India and the Americas beyond the presence of the custard apple, though, then instead of leaping to the conclusion of ancient transoceanic contact, we might question whether the fruit could have been transmitted by some other means, such as by migrating birds, or question whether the same kind of plant might have evolved in different regions independently (as a recent study in Nature Ecology & Evolution has actually observed, in the form of similar leaves evolving independently), or simply question the accuracy of the recent archaeological findings about the custard apple seed remains.

Above, statue holding the mythical bejeweled muktaphala fruit sometimes mistaken for maize, and below that, the carving of fruit suspected to be custard apples.

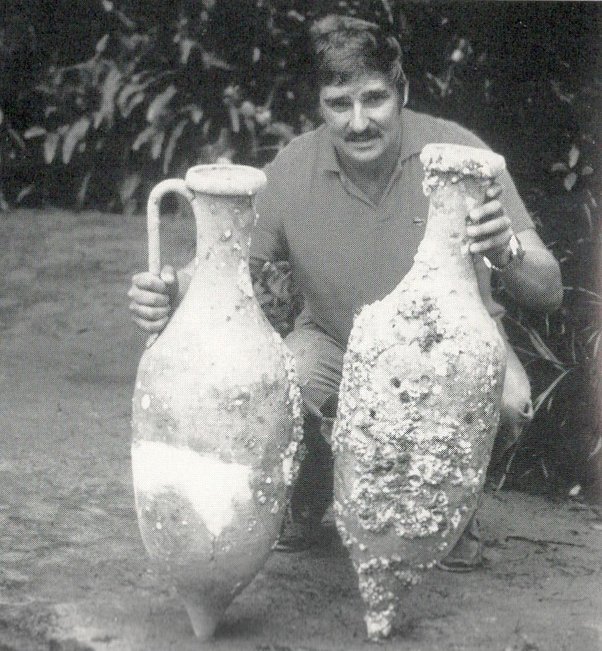

We likewise find similar evidence of ancient Roman contact with the Americas in the form of certain New World fruit believed to be recognized in artwork, as in certain mosaics can be found what appear to be pineapples. Though it is argued by skeptics that these are actually umbrella pine tree pinecones, the depiction of vertical leaves sprouting from the top of them makes this identification somewhat weak. Still, though, in this case, the artwork stands alone and can easily be dismissed as misconstrued. We have no physical, dated evidence of pineapples in the Roman Empire, as there appears to be of custard apples in India. But in the Americas, there have been discovered numerous artifacts that have been claimed to be of Roman origin. In 1924, in Tucson, Arizona, 31 lead artifacts, were found including swords and crosses and religious objects, which bore Roman numerals and Latin inscriptions. In Mexico City, a terracotta sculpture of a bearded head was discovered in 1933 that appears very similar to Roman artwork of the second century CE. And in 1982, in Guanabara Bay near Rio de Janeiro, a diver discovered what appeared to be numerous jars extraordinarily similar to Roman amphorae, vessels with a narrow neck and two handles. It should be conceded that the possibility of a drift event, of a single vessel being swept off course and carried as a derelict by currents between continents, is not impossible. And Romans did have seaworthy vessels. There is evidence that Romans ranged overseas as far as the Canary Islands, after all, and being lost at sea in those waters could indeed result in the Canary Current carrying a ship into the North Equatorial Current, which would take them out across the Atlantic toward Central America and the Gulf of Mexico. For these artifacts to have ended up where they were found, there only needed to be one shipwreck, and in the case of the Tucson artifacts, some survivors who carried them across a strange new land. But of course, all of these artifacts are likely hoaxes. Experts point out that the Tucson artifacts were crudely cast and that their Latin inscriptions are all of well-known works by Virgil and Cicero and thus easy for a forger to have faked. Skeptics have even fingered a likely culprit, a local sculptor known to work with lead and to collect books on foreign languages. As for the terracotta head of Mexico City, skeptics point out that it was discovered not in a 2nd century archaeological site, but rather in a site that was dated to the 15th century CE. Most likely the terracotta head was deposited there either by a modern hoaxer or by a 15th century European. And finally, the seemingly Roman amphorae that were found in the bay near Rio were promoted by an underwater archaeologist known for self-promotion who had run into trouble with the law for illegally selling antiquities. Though not widely reported in America, nothing every became of this discovery in the eighties because Brazilian authorities determined it to be a hoax after a businessman came forward to claim the jars as his property, explaining that he’d had the jars manufactured in Portugal and purposely sunk into Guanabara Bay twenty years earlier in order to increase their worth by making them appear aged.

Though all of these intriguing theories inevitably disappoint under scrutiny, leaving us with only the meager evidence of an ancient fruit seed in India, there is actually more reliable and convincing evidence that indeed at least one other Pre-Colombian Transoceanic Contact Theory besides that of Norse contact with the Americas might actually be true. It seems Lin-Manuel Miranda got it right when, in the animated film Moana, he depicted Polynesian cultures as explorers who “set a course to find / a brand new island everywhere [they roamed].” Theories about Polynesian contact with the Americas developed from the late 19th-century to today, based largely on the similarities between Polynesian watercraft and the unique sewn-plank canoes used by native peoples of the Santa Barbara coastal area of California. Additionally, similarities between bone and shell fish hooks used in both Polynesia and California were considered an additional telltale sign of cultural diffusion. Then there is the diffusion of the sweet potato, which can be seen to have spread from Polynesia across all the Pacific islands, including the very distant Hawaii and Easter Island, all the way to the coasts of Central and South America. Such eastward expansion was long deemed impossible due to the prevailing westward winds, which led Thor Heyerdahl, a Norwegian ethnographer and adventurer, to theorize in the 1940s and ‘50s that the civilizations of South America, specifically the Inca, had made contact and colonized Polynesia by crossing the Pacific in a westerly direction on rafts. Indeed, he even attempted to prove his thesis by undertaking a dramatic crossing of the Pacific on a raft in 1947. However, Polynesian scholars have proven that the area was actually settled from the west, and that Polynesian peoples certainly did expand eastward by sailing against the wind in search of new islands, knowing that prevailing winds would always carry them home. Linguistic evidence also favors this model, with a more convincing etymological case being made that the forms of the same words for plank-sewn canoes and sweet potatoes were in use across the Pacific Basin. Finally, just a few years ago in 2020, a genetic study appeared in the scholarly journal Nature that examined genome variation to determine Polynesian – Native American admixture, finding “conclusive evidence for prehistoric contact of Polynesians with Native Americans.” Thus it seems, as with the theory of Pre-Columbian Scandinavian contact with the Americas, this theory too stands up to scrutiny. And unlike hyperdiffusionist claims, this theory does not erase Native American cultural identities or give credit for their greatest achievements to another culture. So far as I can discern, it doesn’t appear to be a bid to take credit for the accomplishments of New World inhabitants or to lay claim by rights of discovery to New World lands, unlike many other transoceanic contact theories, as we will see in Part Two of this series.

The self-promoting “archaeologist” who publicized his discovery of some fake Roman Jars near Rio.

Until next time, remember the words of St. Augustine, as quoted by Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo to rationalize his suspicion of myths about Pre-Columbian Trans-Oceanic Contact Theories: “When the facts are obscure, it is better to exercise doubt than to argue an uncertain case.”

Further Reading

de Montellano, Bernard Ortiz, et al. “They Were NOT Here before Columbus: Afrocentric Hyperdiffusionism in the 1990s.” Ethnohistory, vol. 44, no. 2, 1997, pp. 199–234. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/483368.

Haslip‐Viera, Gabriel, et al. “Robbing Native American Cultures: Van Sertima’s Afrocentricity and the Olmecs.” Current Anthropology, vol. 38, no. 3, 1997, pp. 419–41, https://doi.org/10.1086/204626.

Ioannidis, Alexander G., et al. “Native American gene flow into Polynesia predating Easter Island settlement.” Nature, vol. 583, no. 7817, 8 July 2020, pp.572-577. PubMed Central, doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2487-2.

Jones, Terry L., and Kathryn A. Klar. “Diffusionism Reconsidered: Linguistic and Archaeological Evidence for Prehistoric Polynesian Contact with Southern California.” American Antiquity, vol. 70, no. 3, 2005, pp. 457–84. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/40035309.

Kamugisha, Aaron K. "The Early Peoples of Pre-Columbian America: Ivan Van Sertima and His Critics." The Journal of Caribbean History 35.2 (2001): 234-VII. ProQuest. Web. 18 Feb. 2024.

Kumar Pokharia, Anil, et al. “Possible Evidence of Pre-Columbian Transoceanic Voyages Based on Conventional LSC and AMS 14C Dating of Associated Charcoal and a Carbonized Seed of Custard Apple (Annona squamosa L.).” Radiocarbon, vol. 51, no.3, 2009, pp. 923-930. Cambridge Core, doi:10.1017/S0033822200033993.

Meggers, Betty J. “Archaeological Evidence for Transpacific Voyages from Asia since 6000 BP.” Estudios Atacameños, no. 15, 1998, pp. 107–24. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25674708.