Pyramidiocy - Part Six: Pyramid Schemes

The transcript of this episode is incomplete, as I use audio clips in the podcast episode. Listen to the episode to hear audio of some of the claims I attribute to certain individuals and programs.

Years before the discovery of the King Tut’s tomb, the world discovered the pharaoh believed to have been his father, Akhenaten, formerly Amenhotep IV. In the late 19th century, his capital city, Akhetaten, was discovered, and his tomb was uncovered in the Valley of Kings in 1907. What we learned about this previously unknown pharaoh was extraordinarily interesting. He has been called the “heretic pharaoh” because he rejected the gods of his forebears and instituted widespread religious reform. He founded his new capital city on the worship of Aten, an aspect of the sun god. One journalist with an interest in Egyptology, Arthur Weigall, wrote a book about Akhenaten, The Life and Times of Akhnaton, in 1910. Weigall saw Akhenaten’s religious reforms as a parallel to the development of Christianity, since he was leading the pagan Egyptians toward monotheism. To get a sense of how credible Weigall’s writing was, and how he leaned toward the sensational, we need only recognize that Weigall was present at the Tomb of King Tut more than a decade later, writing about the discovery, and upon the death of the Earl of Carnarvon, he seems to have started the Curse of the Pharaohs rumor, claiming he’d heard Carnarvon joking around before entering the tomb and saying he predicted that, “if he goes down in that spirit, I give him six weeks to live.” Like many a propagator of false ideas, Weigall actually claimed that he did not believe in the curse himself, even though he’s the one who seems to have gotten people started believing in it. This legend would eventually live longer than he did, and when he died, some claimed he himself had been a victim of the curse. His notions about Akhenaten too spawned false ideas that would live far longer than himself. First, Charles Spencer Lewis of the San Jose Rosicrucians latched onto Weigall’s writings about Akhenaten and imagined that the monotheist pharaoh had actually founded the Rosicrucian Order. So yet again, much like the Freemasons, an esoteric order that did not actually appear until the Renaissance Period—or in the case of Lewis’s San Jose branch, the early 1900s—falsely claimed to have first formed in ancient times. Then in 1939, Weigall’s ideas would inspire someone else, this time a far more influential thinker: Sigmund Freud. In his book Moses and Monotheism, Freud reimagined the story of Exodus through the lens of Weigall’s biography of Akhenaten, imagining that the heretic pharaoh was actually the unnamed pharaoh of Exodus, and that Moses was actually one of the chief priests of his new religion, who after Akhenaten died had actually led a group of those faithful to the sun god, Aten, out of Egypt, inspiring the story of Exodus. Freud draws his conclusions very confidently, assured that his science of psychoanalysis allowed him some deeper discernment than any Egyptologist or Bible scholar or archaeologist or historian actually trained and qualified to prove such things. Should anyone take his claims seriously, they would do well to recall that Freud also believed his psychoanalytical skills allowed him to discern that the works of Shakespeare had been written by someone else, and I’ve done my best to demonstrate how wrong that is. Freud’s ideas about Akhenaten would outlive him as well, with some later writers revising him to claim Akhenaten was Moses, and that Christianity was actually derived from a cult that worshipped Tutankhamun. But perhaps the most outrageous modern claims about Akhenaten come from astronomer and UFOlogist Jacques Vallée, who I believe was the first to suggest that Akhenaten was actually not worshipping the sun, but rather, a flying saucer. The confusion seems to have been borne out of the fact that Aten was a particular aspect of the sun god, namely the sun disk, as it has been translated. The simple word “disk” appears to have fired Vallée’s UFO-addled imagination, but in reality, the word could just as accurately be translated “circle,” and hieroglyphic depictions of Akhenaten’s worship of a bright yellow circle in the sky with rays emanating from it can only be interpreted as sun worship if one is honest with oneself and makes no leap in logic to a far less likely conclusion simply because one wants to believe it. But this is far from the only connection between Egypt and less than honest fringe ideas about alternative history and ancient aliens that still circulate today.

The story of the ancient astronauts theory and its connection to the pyramids can be traced back long before Vallée, but not that far back. In the late 19th century, the very first ancient astronaut grifter, Helena Blavatsky, made claims about aliens from Venus having been in contact with ancient peoples and having influenced the evolution of mankind. Later Theosophists, like Blavatsky’s successor as leader of the Theosophical Society, Annie Besant, would eventually claim even more specific knowledge about the development of extraterrestrial life and its intercourse with humanity. One theosophist, W. Scott-Elliott, expanded on the connection of these astral visitors with ancient lost civilizations, such as Atlantis, a key element of theosophical pseudohistory and of modern ancient aliens claims. The ideas of theosophists would inspire many during the 20th century. In my episode Technological Angels, about the religious dimension of UFO belief, I discuss how theosophical claims cropped up time and again in UFO religions. Well, these ideas also made a major impact on a certain fiction writer working in the early 1900s: H.P. Lovecraft. Lovecraft also had a long interest in myths about Egypt and the Pyramids. In 1924, during the Tutmania that ensued after the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb, he ghost-wrote a pulp fiction story for Harry Houdini about the celebrity becoming trapped in subterranean passages beneath the pyramid, confronting undead mummies and demonic gods. He also tried his hand at a vengeful mummy tale in 1935. But the influence of theosophical ideas and other myths about the pyramids become more prominent in his Cthulhu mythos, which featured ancient extraterrestrial gods that had previously been known to ancient peoples. Lovcraft featured all the same ideas about extraterrestrial contact with Atlantis, and Atlantis’s founding of Egypt before its destruction. Even his notion of the magical Necronomicon written by a “Mad Arab,” seems to have been inspired by medieval Islamic works that transmitted myths about the pyramids, as described in my principal source for this whole series, and just an all around great piece of research, The Legends of the Pyramids by Jason Colavito. It is because of the work of Lovecraft, likely moreso even than the occult works of theosophists, that the notion of ancient contact with aliens came to be so common in the public imagination. In the 1950s, they spawned many another pulp fiction tale like them, and some even masqueraded as non-fiction, like the so-called Shaver Mystery published by Ray Palmer in his pulp magazines. These bonkers stories by Richard Sharpe Shaver claimed knowledge of an ancient, technologically advanced civilization that resided underground. Palmer is often credited, as I’ve discussed before in a patron exclusive, with inventing the myth of extraterrestrial flying saucers because of his involvement in the very first saucer sighting incidents, the first involving Kenneth Arnold and the second the Maury Island hoax, which he latched onto as proof that the Shaver hoax he’d been profiting by, about underground creatures piloting spaceships, was real. The art that he commissioned for his magazines, featuring many a flying disk, certainly contributed to the craze. Another science fiction author who would be very influenced by all this pulp fiction about ancient astronauts was L. Ron Hubbard, who would go on to found his own religion based on a myth about ancient extraterrestrial contact with Earth. By the 1960s, the idea was so engrained in the American zeitgeist that it regularly cropped up in sci-fi television programs like Star Trek.

This science fiction story set in Egypt was attributed to Houdini but actually written by Lovecraft.

Lovecraft’s influence on the nascent theory of ancient extraterrestrial contact was more than is more than just speculative, as Colavito has pointed out in more than one. The first major “non-fiction” work to seriously put forward the thesis outside of theosophy was 1960’s The Morning of the Magicians, a French work by journalists Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier. This book blends alchemical lore, New Age spiritual philosophy, legends about Naxi occultism and the Hollow Earth, and UFOlogy. One entire section is devoted to “vanished civilizations,” which they connect to Egypt. They recycle myths about biblical giants, they rely on the Atlantis nonsense of Ignatius Donnelly, they recycle the pyramidology of Piazzi Smyth to claim some advanced technology must have been involved in the pyramids’ construction, and they point to the Sūrīd legend’s tidbit about magic spells that make stone blocks fly into place to suggest they possessed some sort of extra-terrestrial levitation technology. And they were intentionally nebulous about the reliability of their sources and the accuracy of their claims and conclusions. In the preface, Pauwels states trickily, “This book is not a romance, although its intention may well be romantic. It is not science fiction, although it cites myths on which that literary form has fed. Nor is it a collection of bizarre facts, though the Angel of the Bizarre might well find himself at home in it. It is not a scientific contribution, a vehicle for an exotic teaching, a testament, a document, a fable. It is simply an account—at times figurative, at times factual—of a first excursion into some as yet scarcely explored realms of consciousness. In this book as in the diaries of Renaissance navigators, legend and fact, conjecture and accurate observation intermingle.” He says, at least in this English translation, that it’s not a document; ponder that for a moment. And to further confuse what might be fact and what conjecture, he says, “so as not to weigh down the book too much, we have avoided a multiplicity of references, footnotes, and bibliographies,” which is very unhelpful. If they had documented their sources more diligently, they likely would have made further mention of Lovecraft, who is only mentioned once, his science-fiction writings praised as “a sort of Iliad and Odyssey of a forward-marching civilization.” The fact is, the authors were great fans of Lovecraft and were even responsible for translating his work for French readers. And taking it a step further, one of the authors, Jacques Bergier, in his 1970 book Extraterrestrial Visitations from Prehistoric Times to the Present, insinuated that Lovecraft based his fiction on obscure but factual sources. Nor was he the first to have claimed that Lovecraft’s work was secretly accurate in its depictions of ancient alien gods. But by this time, the ancient astronauts myth had spread, and its most effective proponent, Erich von Däniken, had appeared. So heavily did he draw from The Morning of the Magicians that Pauwels and Bergier threatened to sue him if he didn’t give them source credit, which he eventually did.

There is much I’d like to say about Erich von Däniken, much that deserves to be said about the claims in his 1968 book, Chariots of the Gods? As well as all its follow-ups, which did away with the question mark in the title and the caveat that it represented. A thorough reckoning of von Däniken’s claims about, for example, ancient civilizations in the Americas, is beyond the scope of this series, so let us only look at his misunderstandings or misrepresentations about Egyptian history and the pyramids, as well as his propagation of old myths and legends. Of course he relies on the idea that there is no way Egyptians themselves built the pyramids, presuming they’re the work of some precursor culture. That’s the old falsehood about the Followers of Horus borne out of the Inventory Stela, which as I discussed, was a pious fraud. Also, in claiming that in Cheops’s or Khufu’s time there was no such engineering technology, he not only ignores the evidence of the Great pyramid itself, but he also ignores or purposely omits the entire archaeological record of the development of pyramids, from mounds to mastabas to step pyramids, which show the gradual development of this engineering, including the imperfect pyramids built by Khufu’s father, Sneferu, such as the Bent Pyramid, sometimes called Sneferu’s Snafu. He then relies on Arab legends, specifically the Sūrīd legend, for an alternative story of its construction. What he does not emphasize, however, is that this legend did not appear until the Middle Ages, thousands of years after the pyramids’ construction, among the conquerors of the region, not among native Copts. It becomes exceedingly clear, however, that von Däniken is mostly interested in these Arab legends because of his notion that Sūrīd was identified with Enoch. Now, there is a basic problem with this, in that Enoch is identified with Hermes Trismegistus, who in turn was a Hellenization of Thoth and Hermes. In Islamic legend, there was a prophet named Idris who was conflated with Enoch/Hermes, and while it’s true that some early versions of the Sūrīd story present him more like a priest than a king and may have been inspired by stories of Enoch foretelling the flood, it is not an explicit connection in the Arab literature von Däniken cites. Rather it is a later connection suggested because of the names Sūrīd and Idris sharing the same consonants. Regardless, the real problem is that von Däniken piles legend on conjecture, presenting dubious claims as if they are evidence. For example, he says Enoch was abducted by aliens and was taught the engineering needed to build the pyramids, and this is pure fantasy inspired by the single line that God “took” Enoch, a verse in Genesis that would later be taken to mean that he was translated to heaven while still alive, and that would be expanded on in rabbinic literature and apocrypha as stories about his becoming an angel or even a kind of second God. You can hear all about it in my episode the Secrets of Enoch. In making of the story a tale of alien abduction, von Däniken is writing his own fictional version of an already apocryphal legend. And then he leans into the myth of Enochian Pillars, by way of a Hidden Book legend and that pesky legend of the secret Hall of Records that would one day be revealed. And to top it off, he invents a massive conspiracy, involving all archaeologists ever, to suppress the truth. As we will see, for such nonsense to be spread today, much like denialist claims, it has to rely on untenable massive conspiracy claims.

Von Däniken’s book, which popularized the ancient astronauts theory, promises “amazing facts” about the pyramids on its cover.

The publication of von Däniken’s book created something of a sensation, dubbed “Dänikenitis.” It was serialized in the National Enquirer in 1970, and in 1973, his work was adapted into a documentary titled In Search of Ancient Astronauts, hosted by Rod Serling, of Twilight Zone fame. In it, they emphasized some of the false pyramidology of Charles Piazzi Smyth that von Däniken had dutifully included in his book. This documentary was nominated for an Oscar and would eventually be turned into the ongoing television series In Search Of…, hosted by Leonard Nimoy. Eventually, Dänikenitis waned in the face of irrefutable debunking by archaeologists, but in the 1990s, after a 25-part German docuseries revived his claims, von Däniken started writing again after a lull of more than a decade, and then the History Channel got in on the nonsense, premiering Ancient Aliens in 2010. In my series on Oak Island, I marveled at the long-running History Channel series on that topic, but Ancient Aliens has it beat by far. Its 21st season premiered just last week, and the previous season started in January and wrapped up in March. They are pushing out nonstop episodes. Not all of the series is about Egypt, of course, but what is follows much of the same old baloney, a lot of it just the long disregarded claims of Charles Piazzi Smyth, repeated ad nauseum since the 19th century. They talk about the orientation of the pyramids in relation to the cardinal directions as if building something with a mind toward how the morning or evening light will strike it is unthinkable. They take an old Piazzi Smyth claim about the Great Pyramid’s latitude and longitude lines crossing the most landmasses, making it somehow the “center” of all landmasses, which already was both untrue and nonsensical, and which von Däniken misquoted as meaning the pyramids had been built on the world’s “center of gravity,” which makes even less sense, and they take it further, drawing lines not from latitude and longitude, which of course wasn’t even invented until Eratosthenes in the 3rd century BCE, to instead using lines drawn from its faces and corners, which of course pass through a lot of landmasses, since they’re basically going in all directions around the world. They repeat many of the same measurement claims that go all the way back to Piazzi Smyth, about side lengths and height corresponding to the world’s dimensions, without acknowledging where these ideas came from or the fact that Smyth had to invent a new measurement unit, the pyramid inch, for the math to work. And they add some additional but no less bonkers claims about the coordinates of the pyramid corresponding to the speed of light, our system of which was only developed in the 17th century by René Descartes. Not only is it a major assumption that aliens would think in terms of latitude and longitude and Cartesian coordinates, it also doesn’t quite work. The number they take to correspond to the speed of light is only a latitude that passes through the Great Pyramid. Without the other half of the coordinates, it does not give us a precise location, and according to Snopes, that latitude does not even pass through the center of the pyramid but rather just intersects a portion of it.

The program also makes much of the supposed star alignments of the Great Pyramid’s openings and shafts, which as I discussed earlier in this series has been an obsession of pyramidologists ever since John Herschell imagined its entrance passage was directed at Draco. Many are the claims about shafts in the pyramid being aligned with Sirius and Orion’s Belt. That last alignment should give you pause, as it is not a single star but rather a grouping of stars. How, you may ask, does an opening align with more than one star? The simple answer is that openings in stone are not telescopes. Think about this. John Herschel thought the entrance to the Great Pyramid had been oriented to align with Draco, but in a larger opening like a door, one can see an entire swathe of the night sky. And even through the smaller shafts, such alignment is not perfect. Also, spying out stars through long stone shafts doesn’t make stargazing easier. The equally false notion that the tip of the pyramid was used as a platform for stargazing would at least make some sense as an open-air observatory would work far better than peeping at a star through a 240-foot shaft. Pyramidologists and Ancient Aliens talking heads say that these shafts were created to observe the passage of stars, which we should also think a little harder about. Stars move. We observe them with the naked eye or with telescopes that can also move to follow them. A shaft in stone actually makes for the worst possible observation point for the passage of a star, since it only allows a view of that star at one position, at certain times, after which, you’d just have to leave the pyramid and look up to see it. Some versions of this claim assert that they were directed to observe specific “transit points,” which sounds good until you realize that transit points of stars are when they are occluded or obscured from view by other heavenly bodies. It is just nonsensical, and yet so many people believe that the star shaft claim is a given, a proven fact. Nor are these the only sort of stellar alignments that pyramidologists who appear on Ancient Aliens claim have been proven. They will also claim that the layout of the Giza pyramids, as seen from above, is an exact match with the stars of Orion’s Belt. This notion goes back, but not far back, to the 1980s, when writer Robert Bauval, picked up a certain work of pyramidology, The Sirius Mystery, in an airport, and inspired by its claims that the monuments of the Giza plateau corresponded with the star Sirius, thought he could one-up the idea. In his book, The Orion Mystery, influenced by Hermetic legend and the alchemical notion “As above, so below,” which was said to have been inscribed on the Emerald Tablet, he laid out his Orion correlation theory claiming that the pyramids were an exact match of the constellation above. Afterward, he was roundly refuted, not only because Zodiac constellations were known in Mesopotamia and not known in Egypt until the Graeco-Roman era, and not only because Bauval had inverted his diagram of the pyramids to make it fit the constellation, but also because it still did not quite match up. Despite his debunking, his ideas continue to be repeated, attributed only with vague phrases like “scholars claim,” on the History Channel, and he would later go on to repeat the same theory in a book he co-wrote with our next major spreader of misinformation, Graham Hancock.

A promotional image for the History Channel program features the pyramids, a favorite topic of the series, prominently.

In episode one I name dropped Hancock as a grifter, and immediately I received some tersely worded emails from Hancock fans, though this shouldn’t have come as a surprise to them if they really listened to the podcast, as I have called out Hancock in the past for his spreading of myths about the Ark of the Covenant at the beginning of his career, and for his propagation of the old racist myth of a lost mound builder race more recently. To his credit, he has not focused on ancient astronauts claims in his work, though he has appeared on 18 episodes of Ancient Aliens and did promote the idea that a sphinx and pyramids could be seen in photos of the Cydonia region of Mars, which I spoke about in my recent Patreon exclusive. Rather, he has gone the route of Ignatius Donnelly, using all the Victorian-era and early-20th-century pseudohistory and pseudoscience at his disposal to argue that monuments all over the world are evidence of a high-tech ancient civilization, which he identifies as Atlantis. There is just so much to address when it comes to the work of Graham Hancock that I won’t be mounting a complete examination of his arguments here. Instead I’ll limit myself to his misinformation on the pyramids. In one of his first books to discuss Egypt, The Message of the Sphinx, he not only promotes the claims of Rosicrucians and the psychic Edgar Cayce about secret records to be found beneath the Sphinx, as I mentioned in the last episode, but he also promotes the idea that evidence of Khufu having built the pyramids was fraudulent. I mentioned this previously as well. Howard Vyse, who dynamited the entrance of the pyramid in 1837, discovered the cartouche of Khufu within. This cartouche is part of the pyramid laborers’ graffiti I’ve discussed that indicates workers were not slaves and actually identified themselves as “friends of Khufu.” The notion that Vyse forged this cartouche actually originates in the work of ancient astronaut theorist Zechariah Sitchin, who has made a great many claims about a phantom planet peopled by Sumerian gods. Sitchin argued that the name in the cartouche was not quite right, not the name Khufu would have used, when actually, more than one cartouche was found within the Great Pyramid’s nooks and crannies, and more than one version of Khufu’s name is present, in abbreviated form and more formal forms. Moreover, the fact that some of these cartouches can be seen deep within the masonry, meaning that they must have been applied before the stones were set in place, proves they weren’t added in the 19th century. To his credit, Hancock quietly retracted the claims two years later, but if you look up the Vyse cartouche or Khufu cartouche today, Google gives you mostly a lot of conspiracist blogs still claiming it’s a fake.

More recently, with his books Fingerprints of the Gods and Magicians of the Gods, he has gone full bore pyramidologist in his commentary on the pyramids. In Fingerprints, he repeats all the claims I refuted back in episode one about pi and the Golden Ratio having been purposely encoded into the pyramid’s dimensions and about its correspondence with the Earth’s dimensions, yet he only cites the obvious source of these claims, Charles Piazzi Smyth, without naming him except in a footnote, instead generously referring to him as “a former astronomer royal of Scotland.” To his credit, though, he avoids Smyth’s reliance on “pyramid inches,” finding number correspondences instead in the metric system, which would have made Smyth roll over in his grave. In Magicians, he claims that the if the height of the pyramid is multiplied by 43,200, you get the polar radius, and if you divide the perimeter of its base by the same number, you get the equatorial circumference. In reality, the results he gets vary widely off the mark, with his equation using the base being about 273 kilometers short of the actual Earth circumference, and his equation using its height giving a result 763 kilometers short of the polar radius. More than that, though he acts as though it is so precise, he is working from imprecise estimates of the pyramid’s dimensions, since without its casing stones, we don’t know exactly what its height and side lengths originally were, a fact he himself admits. So what he does is tout the superhuman precision of this engineering, while handwaving any inconsistencies as the errors of its human builders. He can’t have it both ways. But of course, all of this is really to lead to his further smoking gun that the number 43,200, the factor that allows his equations to work, is actually a representation of the Earth’s axial precession, its wobble as it spins on its axis. If you trust Hancock, this demonstrates that ancient Egyptians had very advanced knowledge about the Earth’s rotation. But you should not trust Hancock. His claim derives from the cycle of precession in years, which he says takes 25,920 years. This is already off, since he’s taking an outmoded calculation that’s about 150 years longer than what modern astronomers calculate. Regardless, the number is far short of his 43,200, so how does it correspond? Here’s where Hancock really stretches things. The two numbers share some common factors. The two numbers are both multiples of 72 and 360. What he’s doing here is recycling yet again. The notion of certain numbers being “precessional,” and of the measurements of megalithic structures revealing that ancient cultures had knowledge of axial precession because these numbers are factors of the measurements, goes back to a long-discredited 1969 work on archaeoastronomy called Hamlet’s Mill. Not only did the book’s arguments rely on outdated etymology, its claims about the presence of precessional numbers were very simply refuted, because the factors they kept seeing were simply a result of the Sumerian counting system having a base of 60 and their having a calendar with 12 lunar months of around 30 days. But we need not even rely on this explanation to refute these claims about ancient Egypt, since the Law of Small Numbers, which I discussed in my episode on Pythagoras and Numerology, proves that simple coincidence can easily result in the finding of certain numbers when reducing any large number to its factors. Like most pyramidology, this is just numerology masquerading as Egyptology. But Hancock not only mistakes coincidence for ancient advanced knowledge. He also spreads outright myths and science fiction, presenting them as potential scientific truths. For example, ever eager to sow doubt in “orthodox” archaeology, he’ll claim that any rational explanations of how the pyramids were built are actually lies being purposely spread by academia. But then he will turn around and suggest the most outlandish explanation himself, that they were built by levitating stones into place. He calls these “ancient Egyptian traditions,” and I believe he knows better. He’s too clever and well-read to really believe that these are ancient Egyptian traditions. This idea about magically floating blocks into place originates, of course, from the Sūrīd legends I’ve already described, which did not arise until the Middle Ages, thousands of years after ancient Egyptians built the pyramids, written by Arab conquerors who could not read Egyptian hieroglyphs and who let their imaginations run wild in crafting a myth about the pyramids. This is why I call Hancock a grifter. I believe he knows when he is misrepresenting evidence or not being forthcoming about the sources of his ideas, and I don’t believe he really thinks archaeologists are all involved in a massive coverup. But to be very careful with our phrasing, since grift means small-scale swindling, I suppose he’s not a grifter, since he is swindling the public on a rather large scale.

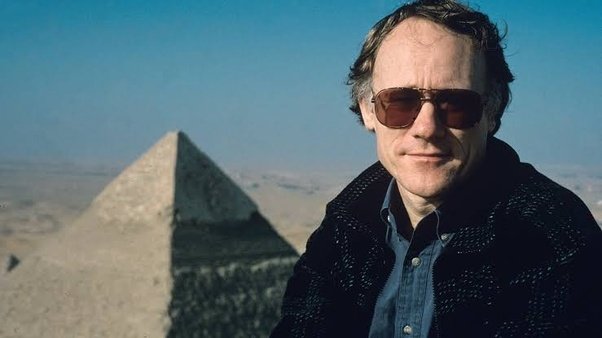

Graham Hancock posing with one of his favorite topics: the Giza pyramids.

I think that some take umbrage with me calling Hancock a grifter because, on the spectrum of fringe pseudohistorian grift, his brand is convincingly earnest. Many think that he really believes what he promotes. The same cannot be said for the other pyramid myth grifter that I mentioned in the same breath in the first part of this series: Billy Carson. In some ways, Billy Carson is one of the reasons I felt compelled to finally tackle this huge topic. Because I seek out pseudoarcheology and pseudohistory on social media in an effort to learn what kind of misinformation is trending, I frequently find Billy Carson showing up in my feed. He is a prolific podcast guest, and having appeared on Joe Rogan recently, he has achieved some fame and reach. Here at the end of my series, it seems very difficult to adequately address all of Carson’s wild claims, but I’ll give it a shot. He recycles the claims of that original grifter, Madame Blavatsky, about the existence of the Akashic field. He claims it was written about in the Emerald Tablets, which he says really existed. He refers to the tablet, singular, and the tablets, plural, claiming both were engraved in stone and originate in antiquity, acting like actual tablets can be viewed in the Cambridge Library. As we know, there is no tablet in existence. The tablet is legendary, and the text supposed to have been on it only appeared in the Hellenistic Period at the earliest, and maybe as late as the fifth century CE—nowhere near the antiquity supposed. The other, plural tablets he refers to are a hoax perpetrated by an occultist in the 1920s who claimed he found emerald tablets in the Great Pyramid and translated them, but much like Joseph Smith, couldn’t show anyone the actual tablets. So we have Carson here referring to a certified grifter’s hoax to support his claims about the Emerald Tablet, which he has written whole books about, making of them a kind of self-help text, selling them to the public. As for his claims about the pyramids, they are astonishing and seemingly never-ending. He recycles the old Piazzi Smyth nonsense so widely repeated on the History Channel that they are located at the center of Earth’s landmasses. He also repeats the claim about the pyramids matching up with Orion, but also that structures on the Giza Plateau somehow represent a map of the solar system, “down to the millimeter,” even. I’m sure Billy has the proof of that… but how would that even work since planets do not remain immobile to be mapped? Well, like everything Billy says, he is just repeating someone else’s claim, which is a fringe claim not that it maps the solar system, but rather that it predicts some future date when planets will align in similar positions. But Carson doesn’t stop to expand or support any of these claims.

His style of argument is the Gish gallop, overwhelming those who listen with excessive claims without regard to their strength or accuracy. He’ll claim that the pyramids are on the 33rd parallel, repeating the claims about a mystery circle at that latitude, on which many megalithic structures were built. No matter that the pyramids are actually on the 29th parallel; he’s already on to the next claim, that the height of the Great Pyramid represents the average of all mountain heights on Earth. Well, this doesn’t seem possible, since it’s only about 147 meters tall and many mountain peaks are thousands of meters high, but how are we to disprove the claim, since many mountain peaks on the planet have never even been surveyed. You might want to point out, then, that the claim itself can therefore not be supported, but he’s already on to the next, claiming that the pyramids were power generators. His assertion that water passed under and was pumped into the pyramids is based on no evidence beyond the old statement made by Herodotus, mentioned in the first part of this series, about there being a tomb in the middle of a lake within the pyramid, which seems to have been based only on a misunderstanding of the location of the recently discovered Osiris Shaft. And the idea of the water being used to generate power and turn the pyramid into a kind of particle beam accelerator, which was originated in the 1990s by one Christopher Dunn, who just happened to guest on Rogan about a month before Carson did, just falls apart with no evidence of the water channel needed for any such technology to work. Though you might want to slow down and examine that claim further, he’s already talking about the granite coffer inside the King’s chamber, saying it couldn’t have been made to fit a sarcophagus, because he’s too tall for it, as though pharaohs could not possibly have been short, and taking it further, he asserts that the Ark of the Covenant would fit perfectly in it. Not even addressing the fact that such precise measurements are impossible, since we’re estimating when it comes to the cubit measurements mentioned in the Bible, even rough estimates make the Ark quite a bit smaller than the interior of the coffer, such that there would have been more than a foot of empty space on all sides of it. But Billy wants to make another claim about ancient power generators, and the Ark fits that narrative well. Never mind that he makes absurd claims about ancient Israelites having to wear lead plates and rubber boots when handling it, which isn’t in the Bible, of course. In case it’s not painfully obvious, ancient Israelites didn’t have rubber boots.

The audacity of this guy and his absolute nonsense is enough to make you want to look into who he actually is. If you listen to him talk about his origin story, you hear that he first became interested in the fringe as a child, when he saw a UFO. OK, I can believe that he thought he saw something at that age. But then he describes the journey of discovery he went on, researching aeronautics in his school library and somehow managing to hack the Mars rover camera so that he could turn it, and thereby discovering the ruins of an ancient civilization on Mars? I’m going to go ahead and call BS on that. If we can’t trust Billy’s autobiography, than we may look to what others have found when researching him, such as financial planning YouTuber Jayson Thornton, who does the world a service by exposing scammers in his content, who uncovered some interesting things about Billy Carson’s background. According to Thornton, Carson, who says he was educated at MIT and Harvard, holds no degrees from those institutions, but rather completed some free, 6-week certificate programs they offer. And Thornton also dug up some documents from the Broward County Sheriff’s Office that show Billy Carson has a criminal record, under the name William Karlson, having been arrested for fraud in 2013 and afterward changing his name. Although this certainly does appear to be strong evidence that Billy Carson was a grifter by any definition, Carson threatened to sue him for defamation if he did not take down his videos. So, there we are. I won’t be surprised if I too get a cease and desist from Billy Carson, though I may be too small a fish for him to notice. All I’m doing here is pointing out the inaccuracy of his claims and reporting what others have reported about his background. But this is the world we live in now. Someone may make a career based on spreading falsehoods and myths, and if a skeptic points out that they don’t appear to be genuine, legal action can be taken against them. And in this world, in which Egyptomania is clearly alive and well, judging just by how frequently guests on Joe Rogan, the most popular podcast in the world, with nearly 15 million listeners, bring up the pyramids, it seems interest in ancient and medieval myths and Victorian legends and long-disproven misconceptions and impossible to credit conspiracy theories about Egypt and the pyramids are far more appealing than the real history of these fascinating wonders of the ancient world. And it’s this foolishness that led me to call this series Pyramidiocy.

Further Reading

Brier, Bob. Egyptomania: Our Three Thousand Year Obsession with the Land of the Pharaohs. St. Martin’s Press, 2013.

Colavito, Jason. The Legends of the Pyramids: Myths and Misconceptions about Ancient Egypt. Red Lightning Books, 2021.

El-Daly, Okasha. Egyptology: The Missing Millennium; Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings. Routledge, 2016.

Hornung, Erik. The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West. Translated by David Lorton, Cornell University Press, 2001.

Kasprak, Alex. “Is The Great Pyramid of Giza's Location Related to the Speed of Light?” Snopes, 9 Sep. 2018, www.snopes.com/fact-check/pyramid-location-speed-light/.

Lehner, Mark, and Sahi Hawass. Giza and the Pyramids: The Definitive History. University Chicago Press, 2017.