Blind Spot: The Secret of Rennes-le-Château and Abbé Saunière’s Riches

François-Bérenger Saunière a staunch anti-Republican from a family of monarchists, received his appointment to the parish at Rennes-le-Château on June 1st, 1885, and within a couple years, he had begun to work on renovating the old tumbledown church, starting with its altar, which is said to have rested on Visigothic stone pillars, one of which was hollow and contained the notorious cipher parchments, according to Plantard’s hoax. But it does appear that Saunière had taken to exploring the grounds of his church and that he had indeed discovered at least some artifacts of interest, such as the ancient carved stone depicting a soldier and child on horseback that some have taken as proof for the survival of the Merovingian line, another thread exploited by Plantard in his masterful hoax. By 1897, we begin to see signs of Saunière’s penury having unaccountably abated, as he began to spend money on decorating his church, with statuary and other artwork that many would eventually puzzle over. In 1899, his mysterious influx of money could not be denied, for he bought land surrounding the church—all in his housekeeper’s name, Marie Dénarnaud—and began to build an ostentatious estate, a grand tower, a fine promenade, and even greenhouses for the growing of oranges. He died of a heart attack in 1917, and today, thanks to the bestsellers of Henry Lincoln and Dan Brown, the mystery of his sudden wealth endures, drawing far more visitors to his parish today than it ever received during his own life. But is there a genuine mystery here? Is this a story of hidden treasure or conspiratorial intrigue or revelatory discoveries?

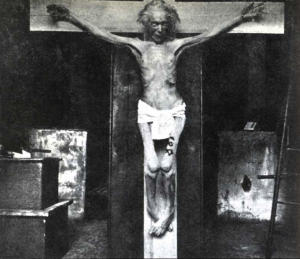

Many in the past and even today scrutinize the chapel’s decorations for clues as to the nature of Saunière’s secret, believing them unusual and therefore suspecting that the parish priest had been sending coded messages through them. Henry Lincoln and those who persist in giving weight to his theories see much in them. The church’s dedication to Mary Magdalene, for example, is seen as evidence of Lincoln’s grail theories, but really the Magdelene is an important figure from the Gospels, a beloved disciple, so is there any real difference here than if the church had been dedicated to any other disciple? As I’ve already talked about extensively, people tend to see what they want to see: with little effort, statues of Joseph and Mary cradling the Christ Child become, in the eye of the credulous beholder, statues of Jesus and the Magdalene holding their child; and the landscape in the back of a painting of Mary Magdalene can be construed, with some imagination, as corresponding to imagery in a painting by Teniers, taking one down that old hoax path once again; and statues of different saints in the church’s nave can be viewed as being placed in such a way that the first letters of their names spell out the word graal, or grail, though you have to go looking for the L elsewhere in the church, among the bas-reliefs rather than statues in niches. And not only do some read into the artworks too deeply, looking for what they want to see, but also they misread them. Many consider the inscription over the chapel’s entrance to be unusual, Terribilis Est Locus, translated as “This place is terrible,” but a better translation may be “This place is awesome,” for it appears to be taken from Genesis, chapter 28, when Jacob, realizing God was in a certain place, declared, “How dreadful is this place!” Therefore, taken in this way, it’s actually quite a natural inscription for a church, where the awe-inspiring presence of God is mean to be felt and feared. One statue in particular at Rennes-le-Château especially troubles and mystifies: a devilish depiction of the demon Asmodeus kneeling beneath a baptismal font greets you as you enter. Some take this as a confirmation of the secrets of the church, for Asmodeus is a guardian of secrets and, more specifically, of the treasure of Solomon’s Temple. But a simpler explanation is that Saunière saw it as representing the Republicanism he detested. In an anti-Republican sermon he gave, his sentiments are clear: “The Republicans, now there’s the devil to be conquered and who needs to bend its knee under the weight of Religion and baptisms.”

The statue of Asmodeus at Rennes-le-Château, via Blogodisea

If the church and its decorations are not the cryptic clues that many take them for—and why would they be? If Saunière had a secret, why would he be coyly broadcasting it with such hints?—then we must turn to logic and reason out how he may have found himself so suddenly in money. The implication of Henry Lincoln’s theories, in the book Holy Blood, Holy Grail, is that, rather than stumbling across a genuine treasure, Saunière discovered a secret that earned him money. By Lincoln’s reckoning, it was a secret about Christ that would shake the church to its foundations, and therefore Saunière must have blackmailed the Vatican for the money he came into. But if one looks at Saunière’s life, there are problems with this theory even above and beyond all the issues I reviewed in the last episode. In 1908, Bishop de Beauséjour, a bureaucrat, took an interest in Saunière and his unaccountable wealth and began to investigate him. By 1915, he had stripped Saunière of his title under accusations of trafficking in masses. This certainly doesn’t sound like a church that had been brought to heel by the dangerous secrets Saunière held.

So if the money did not come from a mysterious secret with which Saunière blackmailed the church… must it have come from treasure? Henry Lincoln and others have been led to believe that it was a Templar treasure. The Templars, of course, had amassed great fortune and perhaps many priceless relics, whether it be during their mysterious years excavating the tunnels beneath the Temple Mount, throughout their many conquests during the Crusades, or simply as the guardians of the wealth of others. This was, after all, the likeliest reason for their suppression: the seizure and redistribution of their wealth. The connection to Rennes-le-Château appeared to be through the family of Bertrand de Blanchefort, onetime Grandmaster of the order. There is a Château de Blanchefort in the area, and there had been some nobility with the title of Blanchefort that featured in the region’s history: for example, the tombstone of a Marchioness of Blanchefort took center stage in the Plantard hoax, a forged etching of it being used as the key to solve the apocryphal Saunière ciphers. And this with the fact that some of the names on the list of Priory of Sion leaders had been associated with the Templars and the notion that nearby Château de Bezu had been a Templar stronghold after their suppression led Henry Lincoln to believe Saunière had found a Templar treasure. However, more legitimate scholarship tells us that Lincoln yet again made an unsupported leap in linking Bertrand de Blanchefort to Château de Blanchefort and the Marchioness of Blanchefort supposedly buried at Rennes-le-Château, as it appears the only genuine connection between them is the name. And furthermore, his assertion that Château de Bezu was a Templar stronghold appears to be just as unfounded.

But even dismissing the Templar connection, there are still likely narratives supporting the presence of a treasure. When Catholic Crusaders came through the region in the 13th century to stamp out the gnostic Cathar heretics, it was said that some escaped with the so-called “treasures of their faith,” whatever those were. Of course, that theory resembles the Templar theory in its reliance on speculation, so let us turn to a theory that requires fewer suppositions. We know that Saunière explored the grounds of his church extensively, digging beneath and even disturbing some of the tombs in the cemetery. Could he have found gold, as the legend so often says? Or if not gold, perhaps some precious relic that he sold to the church through some intermediary? In excavating beneath his church, he lifted a flagstone that was in reality a valuable artifact—the carving of the soldier with the child on horseback that Lincoln and others have made much of, which some historians suggest is only a depiction of a Carolingian boar hunt—and it is frequently said that beneath this, he found some old coins and a chalice that he gave to his friend, another priest in a nearby parish, Amélie-les-Bains. The chalice remains there today… but it appears to be a 19th century item that merely mimics the medieval style, so perhaps it was just something Saunière picked up for him in a gift shop. Still, could it be that this was the moment of his discovery? He is said to have told the workers helping him that the coins were medallions of little value and to have sent them home. Perhaps seeing this small bit of treasure, he immediately dispatched them so he could investigate himself, and perhaps he went on to discover more than one cache of coins. As previously discussed, the region had been a stronghold of the Visigoths, who had sacked Rome. Whether or not they carried off the treasures of King Solomon that Romans had earlier taken from the Holy Land, surely they carried off some treasure. This remains, at least it seems to me, a distinct possibility.

The Knights Stone artifact, via Rennes-le-Château Research and Resource

But there is one last treasure theory that we should consider, and this one may indeed lead us to a better understanding of the entire legend. This was the original treasure legend, offered when in 1956 one Noël Corbu first shared the mystery of Abbé Saunière’s wealth to a wider audience in an interview with the newspaper, La Dépêche du Midi (Putnam and Wood 19). Corbu had heard the story of Saunière’s mysterious wealth from Marie Dénarnaud, Saunière’s housekeeper and sole heir. According to Corbu, Dénarnaud had confided to him that Saunière had discovered the treasure of Louis VIII’s wife, Blanche de Castile, an amount of about 18 million francs that was still hidden away somewhere in Rennes-le-Château. The problem is that there is no evidence that any such treasure ever belonged to this this historical figure, let alone that it would have been secreted away in this little mountain village. In truth, Noël Corbu, a businessman, had purchased the lavish estate that Saunière had left behind, Villa Bethania, and sought to make of it a hotel. But Rennes-le-Château was such an isolated place, he didn’t know how he could drum up enough guests to turn a profit. To him, then, the local legend about the priest and his mysterious wealth was a godsend. He cooked up a completely fabricated hidden treasure story, disseminated it through the newspapers, and watched with satisfaction as reservations began to pour in.

Thus even at its very beginnings, the legend of treasure at Rennes-le-Château is steeped in hoax and false history. While the notion that Saunière found some Visigothic artifacts of value beneath his church is certainly plausible, the absolute swamp of fabrication and fantasy that surrounds every part of this mystery makes it difficult to give any theory much credence. So perhaps, then, we should apply the rule of Occam’s Razor to cut through the baloney. What is the simplest and least complicated explanation for his wealth? Well, Saunière was a charming man and does appear to have accepted gifts from wealthy women. Moreover, during the last decade of his life, as Bishop de Beauséjour investigated him, charges of trafficking in masses led to the loss of his title. It appears that Saunière was collecting payment for prayers on a large scale. Bishop de Beauséjour found advertisements that Saunière had placed in Catholic magazines all over France and concluded that he could not possibly have said all the masses for which he had accepted payment. So there you have it; evidence of the source of his wealth, and ill-gotten at that. But could he have possibly amassed great riches this way? In truth, Saunière might not have been so rich as he seemed. Judging from the money he spent does not necessarily give an accurate representation of the money he had, for at the time of his death, as his ecclesiastical trial continued, Saunière was deeply in debt (Putnam and Wood 18).

In the end, like many true historical mysteries, it really depends on what you want to believe. If you have the heart of an adventurer, you may ignore the evidence that suggests the priest was just a charlatan in favor of the idea that there is gold in those hills. And if you’re of a skeptical mind, you dismiss it as fanciful garbage. As we have seen so many times, it is in these intersections of fact and myth, in these areas where faith conflicts with reason, that historical blind spots endure.

Works Cited

Putnam, Bill and John Edwin Wood. "Unravelling the Da Vinci Code." History Today, vol. 55, no. 1, Jan. 2005, pp. 18-20. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=15581603&site=ehost-live.