"An Idle and Most False Imposition"; The Shakespeare Authorship Question - Part Two: The Baconian Heresy

In 1932, The Times Literary Supplement published evidence that questions about Shakespeare’s authorship had arisen decades earlier than the mid-19th century, when they had previously been thought to have appeared. The paper published was from a small 1805 meeting of the Ipswich Philosophical Society, at which one James Corton Cowell presented the 18th-century findings of a clergyman named James Wilmot, who lived near Stratford-upon-Avon and had conducted some research into Shakespeare. According to this document, the Reverend Wilmot around 1795 had gone in search of books that belonged to Shakespeare and had been surprised to not find any in the private libraries of the area. He had been further unsettled not to find anyone able to offer any clear anecdotes about the playwright. Perhaps this Wilmot should not have thought it so odd, since he was asking for anecdotes nearly 180 years after the man’s death, and more than 130 years after the last of his surviving family had passed away, but regardless, the reverend apparently found this suspicious enough that he decided the Shakespeare of Stratford must not have really been the author of the works attributed to him, and instead, he leapt to the conclusion that it must instead of have been Sir Francis Bacon, who was a true genius and luminary of the same years, and who would certainly have had the knowledge of Court life that it seemed Shakespeare must have had. But Reverend Wilmot was disturbed by his theory, and he burned all of his research, or at least, that is the story that Cowell tells in his paper to the Ipswich Society, claiming that he only knew about Wilmot’s conclusions because the reverend had confided in him. At the time that this document appeared, in the 1930s, this was no revolutionary idea, having been popularized in the middle of the previous century. It certainly was curious, though, that this document came from the collection of a devout Baconian, someone thoroughly convinced that Bacon was the real Shakespeare. Naturally, considering the long history of forgeries related to Shakespeare, this too would need to be authenticated. A biography of Wilmot seemed to confirm that he was who the document said he was, that he did admire Bacon and that he had actually consigned his papers to be burned. However, this biography was written by, it turns out, a forger who would later make false claims of having been born into royalty. Her claims about his burning his papers don’t appear to have been true, and moreover, there was no indication even in this unreliable source that Wilmot had ever conducted research into Shakespeare, nor that he had ever had a meeting with James Cowell. Indeed, no strong evidence for the existence of this James Cowell had even turned up. Curious, the author of my principal source, Contested Will, scholar James Shapiro, examined the document printed in 1932 in The Times Literary Supplement, and based on its use of anachronistic language, its knowledge of details that had not been discovered at the time, and other errors, determined that it was likely a hoax. Indeed, there is a long history to the claims that Sir Francis Bacon was the author of Shakespeare’s works, but not so long a history as this forgery would claim. Just as those who were desperate for some historical evidence to corroborate their conceptions of Shakespeare had resorted to many a forgery over the years, so too have those who are desperate to lend credibility to claims that Bacon authored Shakespeare, because without some earlier proponent of the theory, it is often pointed out that the first person to come up with it had been a mad spinster, also named Bacon.

*

When we hear the term Renaissance, which is a French word simply meaning “rebirth,” we of course think of a time of new ideas in philosophy and new achievements in art, and we typically think of Italy. Indeed, it is often argued that the Renaissance began in Florence, with the writings of Dante and Petrarch and the art of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Donatello, Raphael—all the ninja turtles. But of course, the Renaissance was not a strictly Italian rebirth of culture, and elsewhere these developments were seen as well. In England, William Shakespeare is of course counted among the luminaries of Renaissance artistry, as are some of his fellow dramatists, like Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson, and other major English poets, like John Milton, Edmund Spenser, and John Donne. On the list the philosophers who contributed to this rebirth in thought in England, you may see many recognizable names, like William Tyndale and Thomas More, but always atop this list you’ll find Sir Francis Bacon. A true polymath, Bacon was a prolific writer on many subjects, from legal treatises, to politics, to history, to the philosophy of education and knowledge, and to natural philosophy or science, in which field he is credited as a forefather of the scientific method. He wrote every kind of thing, from tracts and pamphlets to political reports and parliamentary speeches…everything but poems and plays, funny enough. He served as a counselor to Queen Elizabeth, and later in legal positions under King James, proved himself a formidable statesman as Lord High Chancellor of England. With some questionable charges of corruption in 1621, he lost his positions and was even confined for a time in the Tower of London, after which he retired and passed away a few years afterward. But just as Shakespeare’s star would brighten years after his death, so too would Bacon’s. During the Enlightenment, the French philosophes esteemed him as a social reformer and opponent of dogmatism, and in the 19th century, he continued to be admired. Ralph Waldo Emerson heaped praise on him in much the same way he did Shakespeare, calling him “an Archangel to whom the high office was committed of opening the doors and palaces of knowledge to many generations.” And two mysterious undertakings in Bacon’s career would end up, during Emerson’s time, encouraging his identification with the works of Shakespeare: the first being that he had never finished his work, Instauratio Magna, the “great restoration,” the final, lost part of which promised to be his “New Philosophy,” and the second being that he had once developed a cipher, acting as both a substitution and a concealment code, that allowed messages to be hidden within texts. As you might already imagine, this would lead to claims that his lost philosophy was hidden within Shakespeare’s works.

A portrait of Sir Francis Bacon at the height of his career.

With the claims about Reverend Wilmot proving doubtful, it appears that the first person to not only claim Shakespeare did not write the works attributed to him but also to actually name Francis Bacon as their true author was Delia Salter Bacon, a remarkable Puritan woman—with no relation to Francis Bacon—who had been born in a rustic log cabin in Ohio. After their Puritan community failed and her father, who had organized it, passed away, her brother was sent off to Yale, but she, who was far more intellectually gifted and eloquent than he, had to remain in their Connecticut home and support the family as a schoolteacher. Yet she would not be held back. She began to win short story writing contests, even beating out Edgar Allan Poe for one prize, and soon she was a popular lecturer on history in New Haven. She moved to New York City in 1836 and began to acquaint herself with the intelligentsia there, such as Samuel Morse, who was then engaged in developing Morse code and, as Sir Francis Bacon was a figure of interest to her, spoke with her about Sir Francis Bacon’s cipher. She became involved with the New York theater scene, befriending a famous Shakespearian actress, for whom she wrote a play with decidedly Shakespearian themes. After the failure of this play, she withdrew from society, beginning to develop a theory about the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays that would preoccupy her for the rest of her life. During the years that she was developing this theory, she also became involved with a man, whom she seemed to believe had intentions of marrying her, but when her family confronted him about his intentions, he claimed he had none and began reading their love letters to people he knew, mocking her for her unrequited expressions of affection. Since the man was a theology student intending to become a clergyman, Delia Bacon’s brother actually took him to ecclesiastical court over it, claiming “calumny” and “disgraceful conduct.” The result was that Delia had to testify, their love letters were made public, and the rumormongering became far worse than it ever might have otherwise been. Delia began to lose her faith over the whole affair, and she would never again be connected romantically to another man.

So Delia Bacon withdrew into her studies, becoming more and more convinced of her discovery that Sir Francis Bacon had been behind the works of Shakespeare. She took the famous writer Nathaniel Hawthorne into her confidence, since he too had a family background in Puritanism, and Hawthorne thought her theory had such merit that he introduced her to Ralph Waldo Emerson. The great essayist Emerson too was quite impressed with Delia’s writings, though he expressed his doubts about her theory quite eloquently: “you will have need of enchanted instruments, nay alchemy itself, to melt into one identity these two reputations.” Nevertheless, she was convincing, for she insisted that she had found secret evidence in Shakespeare’s very works, hidden by the Baconian cipher. So convincing was she that Emerson introduced her to Thomas Carlyle, the famed historian and essayist from Scotland, and arranged for Delia to visit England to further research her theory. Of course, fleeing to England to escape the humiliation of her recent scandal greatly appealed to Delia, so she went overseas, where Carlyle actually laughed in her face about her theory, encouraging her to make use of the British Library, where the extensive materials in their collection should disabuse her of her misguided notions. But Delia Bacon was confident that there was nothing in the library to help her. Instead, she spent her time in St. Albans and Stratford, not completing archival research but rather lurking around the tombs of Sir Francis Bacon and William Shakespeare, asking about having their crypts opened because she suspected that some secret proofs of her theory, such as the lost manuscripts, had been buried with them. According to her theory, Sir Francis Bacon, along with a coterie of co-conspirators, had chafed under royal authority, and believing that his New Philosophy, which was essentially a call to throw off the yoke of monarchy for freedom and knowledge, must be directed to the people, he conspired with these others to circumvent censors and embed this philosophy within a series of plays to be put on for the public. The plays themselves proved it, she claimed. Their message about the evils of kings was Bacon’s. Her evidence was much what we have heard already, that there is no record indicating the Stratford man capable of composing the works. She relied on invective, calling Shakespeare a “stupid, illiterate, third-rate play-actor,” while Bacon was exactly the sort of person one would expect to have written them—both completely unsupported claims since there is no evidence of Shakespeare’s illiteracy and in fact ample evidence that he was quite literate, and likewise no evidence that Sir Francis Bacon was capable of composing the sorts of poetry and plays she was attributing to him.

A photograph of Delia Bacon.

Indeed, there are many other problems with the Baconian heresy, as it came to be called, other than these obvious ones. First, Delia Bacon’s entire argument rested on the content of Shakespeare’s plays being secretly subversive political narratives, and as examples she interpreted Julius Caesar, King Lear, and Coriolanus in such a way as to support this view. It is a remarkable work of what would later be called New Historicist literary criticism, but it is too flimsy to support the conspiracy theory she imagines. She ignores dozens of other plays and all of Shakespeare’s poetry, presumably because it would be a Herculean task to try to interpret all of the works according to this perspective. Moreover, even if her close readings of these plays are accurate, that the politically subversive subtext was intended by their author, that does not prove that Shakespeare, the man from Stratford-upon-Avon himself, could not have intended it. Any philosophical notions about freedom or equality or the tyranny of monarchs that Delia imagines must have come from Sir Francis Bacon were also ideas with which the playwright Shakespeare himself could have wrestled. Her presumption that a “play-actor” from a modest background would not be capable of profound thought and could not possibly comprehend royal court life betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of not just Elizabethan culture but also of human nature in her assumption that only people of high breeding could accomplish anything great, a notion that even her own career disproved. Disappointingly, though, the linchpin of her theory, the smoking gun that she always promised her patrons would clinch the argument, that somehow hidden evidence of the conspiracy could be uncovered using Bacon’s cipher as the key, did not appear in her writings when she published. But to be fair, some of her work was lost. She had the first of four essays published in Putnam’s Magazine, but after a Shakespeare scholar called on by the magazine to introduce the essays refused and suggested they not publish any further works of Delia’s—another genuine example of scholars actually working to silence the authorship controversy, which would only fuel the fires of controversy in the future—Putnam’s did back out of their deal, and when they sent the unpublished essays back to her, they were lost. Having no other copies, Delia Bacon was devastated, but she went to work on writing a full-length book on the topic, writing in poverty and anxious to the point of mental disturbance that someone would steal her theory. Indeed, after her initial essay appeared, a man in England printed a pamphlet making essentially the same claim, minus the co-conspirators, and the same year that Delia finally came out with her book, a long and maundering manifesto that again produced no smoking-gun cipher as evidence, this same Englishman came out with his own book. In the end, Delia Bacon’s work was a flop, as she’d feared. She was thereafter institutionalized, having been driven insane by the entire ordeal, and this, in the end, would so invalidate her theory, since it had been dreamed up by a mad woman, that future Baconians have been willing to forge precursor texts just, it seems, to dissociate the theory from its origin.

Despite the initial failure of Delia Bacon’s work, it proved to be something of a cult favorite, surviving not only in her own work but in the references of others, and among the converts to this Baconian cult were, surprisingly, some astonishing luminaries of American letters who would try to validate the Baconian heresy as a legitimate historical view. Already Delia Bacon had major literary figures like Hawthorne and Emerson writing about her in glowing terms, admiring her intellect and insight. After her passing, Hawthorne portrayed her as a tragic figure in “Recollections of a Gifted Woman,” and Emerson called her “America's greatest literary producer of the past ten years.” Even if they did not subscribe to her theory, they certainly were not dismissive of her accomplishments. Soon, though, another major figure in American literature would become impressed by her, and this masterful writer, Mark Twain, would not only subscribe to her theory but also help to promulgate it. Twain had read Delia Bacon’s work, and throughout his career, he found himself drawn to it. Over the course of his own development as an author, he came to believe that all great fiction was by necessity autobiographical, as was his own—Tom Sawyer, for example, drawn from his own childhood experiences in Mississippi. Therefore he was amenable to the notion that Shakespeare must have written his plays from personal experience, and that, since he had no personal experience of court life, the man from Stratford could not have written them. Twain also knew a thing or two about writing personas, as the riverboat pilot Samuel Clemens had not only written under a pseudonym but also cultivated a character to go with the name. So he imagined that he knew something of what Francis Bacon had done in creating the playwright persona of Shakespeare. And there was no shortage of works to encourage Twain in his thinking during these years, as countless anonymous pamphlets and articles in major magazines appeared during the decades after Delia Bacon’s work, picking up where she had left off, crafting clever arguments in an effort to prove her thesis, or some version of it, as well as to challenge it. In 1886, The Francis Bacon Society began to publish their journal, Baconiana, in whose pages the Baconian heresy would be heartily endorsed and fleshed out. Then in 1888, Twain himself published the first major book-length work on the topic since those of Delia Bacon and her plagiarist. This work, The Great Cryptogram: Francis Bacon’s Cipher in the So-Called Shakespeare Plays, was written by Ignatius Donnelly, a Minnesota Congressman who had found fame writing about Atlantis and ancient catastrophes. Today Donnelly is known as a major figure in the history of pseudohistory and pseudoscience. I mentioned him as a precursor to Immanuel Velikovsky in my series on chronological revisionists because of his fringe catastrophist views of ancient history, and certainly I will be discussing him again whenever I get around to tackling the massive myth of Atlantis. It is unsurprising, since Donnelly was obsessed with the idea of hidden truths and historical cover-ups, that he would be drawn to this topic and predictable that he would focus almost entirely on the idea of the works of Shakespeare being secretly encoded. His work would go on to inspire a generation of Baconian cipher seekers who believed they could decrypt secret messages in Shakespeare.

A photograph of Ignatius Donnelly.

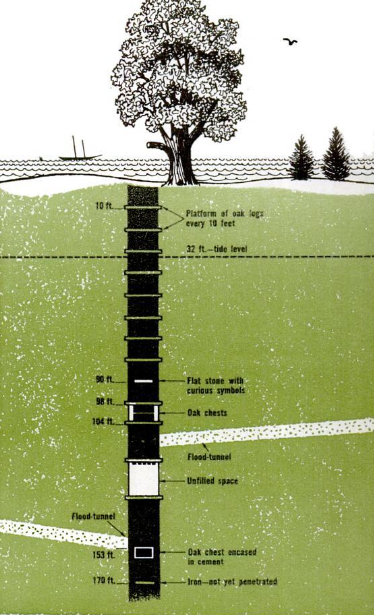

Donnelly was no cryptologist, and he went about his work rather backward, imagining what Bacon’s secret message might be and then searching for it in acrostics. The notion that a work might be misattributed and that the true author’s signature might be discerned in an acrostic, taking the first letters of certain words, was not actually a fringe idea. Indeed, within a decade of the appearance of Donnelly’s book, a work long attributed to Chaucer would be discovered to have been authored by one Thomas Usk because of just such an acrostic signature hidden within it. But Donnelly was forced to choose rather arbitrary key words, separated each time by a rather arbitrary number of characters, for his acrostics to work, and he often miscounted purposely in order to make the text fit his preconceived secret message. Donnelly also imagined how Bacon would have had to lay out his pages in such a fashion as to make sure that each keyword was in the right position, but in doing so he betrayed a clear ignorance of how Elizabethan printing worked. These problems would continue to plague all the theories of later cipher seekers, as would Donnelly’s eventual obsession with finding the original manuscripts of Shakespeare’s works. Authorship theorists regularly point to the absence of manuscripts as some indication that the man from Stratford had not written the works attributed to him, despite the fact that manuscripts of plays written for the stage were often not preserved, since plays could be viewed as a performance art rather than a literary art. Remember that Shakespeare’s collected plays would not be published in the First Folio until years after his death. But to cipher seekers, the absence of manuscripts was somehow proof that they contained evidence of the code written into them, and they imagined that Sir Francis Bacon had hidden them away like buried treasure. This is the origin of the absurd notion that Shakespearian manuscripts are buried on Oak Island. Donnelly believed the manuscripts to be buried on Bacon’s estate but could never convince Bacon’s descendants to let him dig up the grounds.

A photograph of Orville Owen.

After Donnelly came Orville Owen, a Detroit doctor, who claimed that he had found some sort of encrypted manual for decoding Bacon’s code, which he had decoded. So he decoded the key to the code he needed to decode, which, as one skeptic pointed out, seemed “like picking the lock of a safe, only to find inside the key to the lock you have already picked.” Owen claimed that the decoded message instructed him to build a device with wheels on which he would lay out Shakespeare’s plays and spin the text past his eyes in such a way that keywords would jump out. As with Donnelly’s arbitrary selection of keywords, though, Owen baked into his conception of the code much laxity, in that when he found a keyword, it would be possible to find the actual encoded terms or phrases several lines away, giving him great swathes of text in which to find whatever he wanted to find. His assistant in this work, Elizabeth Gallup, would eventually become a rival, believing that Bacon had also woven in a biliteral code through his use of two distinct fonts. Owen’s and especially Gallup’s theories both suffered from the same problem as Donnelly’s in that they depended on the notion that the plays’ author had been closely involved with the actual printing work performed by compositors, but Gallup’s theory specifically would later be entirely disproven when it was pointed out that Elizabethan compositors typically worked with trays full of lots of different typefaces, explaining the variation in font that she suspected was a code. The codes that Owen and Gallup believed they were uncovering led them to pretty outrageous conclusions; according to them, the plays’ cipher revealed that Sir Francis Bacon was really Queen Elizabeth’s son and thus heir to the throne! And Gallup’s nonexistent biliteral code took it a step further, revealing that within the plays were encoded other lost plays of Shakespeare that told the history of Elizabethan England, including tragedies about Mary Queen of Scots and Anne Boleyn, both of which I’d have loved to read. Unfortunately, Gallup only provided summaries of these plays she had supposedly found buried within other plays—taking the idea of a play within a play to absurd heights. Eventually, their decipherment led both Owen and Gallup to the location of the hidden Shakespeare manuscripts: Gallup’s code sent her to North London and Canonbury Tower, while Owen’s took him to the bottom of the Severn River. Unsurprisingly, neither of them found a single page.

Throughout the twilight of Twain’s career and lifetime, a number of other books were released on the topic—Francis Bacon Our Shake-speare by Edwin Reed in 1902, The Shakespeare Problem Restated by George Greenwood in 1908, and in 1909, the year before Twain’s passing, he had the opportunity to read the prepublication galleys of a new book making further claims about Baconian codes in Shakespeare, called Some Acrostic Signatures of Francis Bacon, by William Stone Booth. By the end of his life, Twain had become thoroughly convinced that Shakespeare could not have written the works attributed to him, his conclusions leaning heavily on the fact of the sparse biographical records of the man, saying, “He is a Brontosaur: nine bones and six hundred barrels of plaster of Paris.” Nor was Twain alone among his literary contemporaries in succumbing to the Baconian authorship theory. Walt Whitman, who loved the idea of the mundane world being infused with some mystical secret, wrote the poem “Shakespear Bacon’s Cipher,” which begins with the words “I doubt it not.” And Twain’s close friend, Helen Keller, who had once written “my Shakespeare was so strongly entrenched against Baconian arguments that he could never be dislodged,” would eventually propose to write a book of her own in support of those same Baconian arguments—something she thankfully never did. As for Twain, so preoccupied was he with conspiracy claims about Shakespeare that he tried to come up with a few similar such theories himself, arguing at one point that The Pilgrim’s Progress could not have been written by the preacher John Bunyan and must instead have been authored by John Milton. At one point he even tried to argue that Queen Elizabeth was really a man, because no woman could have accomplished what she did. At the end, the Shakespeare authorship question had become such an obsession that he made it the subject of his final work, which he called Is Shakespeare Dead? In it, he plagiarized an entire chapter from another writer, lifting a whole section about Shakespeare’s apparent knowledge of the law from another book that he failed to credit. So at the end of his illustrious career, the Shakespeare authorship controversy led him to folly and scandal. As James Shapiro points out in my principal source, Contested Will, Twain seems to have plagiarized that section because it makes a convincing case that Shakespeare could not have had the legal knowledge that the author of the plays displays. As Shapiro puts it, Twain borrowed the material “to challenge Shakespeare’s claims to authorship, on the grounds that you had to know something about law to speak with authority about it. Yet in doing so, Twain does what Shakespear himself had done: appropriate what others said or wrote, using their words to lend authority to his own—something that Twain had argued wasn’t possible.” Shapiro goes on to note the further irony that Twain believed Shakespeare to be illiterate because he left no books behind, yet after his own death, Twain’s own book collection was immediately sold off by executors looking to make a quick profit, much as might have been the case with Shakespeare’s library. In the end, with no convincing evidence of a cipher, no lost manuscripts, nor any compelling evidence to show that Bacon wrote any plays, let alone that the language of Shakespeare’s plays could be likened to his known work, the Baconian heresy faded, only to reappear far later with the advent of History Channel nonsense that the conspiracy-addled Internet. But the authorship controversy would not fade. It merely needed a new candidate, and it turned out there was no shortage of them.

Further Reading

McCrea, Scott. The Case for Shakespeare: The End of the Authorship Question. Praeger, 2005.

Shapiro, James. Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? Simon & Schuster, 2010.