The Quest for the Truth of the Holy Grail

I have spoken in previous pieces, and recent posts, about British Israelism, the claim that the British are the direct descendants of the Lost Tribes of Israel, a belief that relies a great deal on pseudo-history and pseudo-archaeology and masks a decidedly racist worldview. Among the additional claims by British Israelists is the story that the prophet Jeremiah traveled, in the company of Egyptian royalty, to Ireland in the 6th century BCE, and with him he carried certain holy relics, the Ark of the Covenant and the Stone of Destiny, also known as Jacob’s Pillow. There are numerous competing traditions in Ireland and Britain about this Stone of Destiny, and as I’ve spoken about before, British Israelists desecrated the Hill of Tara, near the Irish contender for the Stone of Destiny, the Lia Fáil, in their efforts to uncover the resting place of the Ark. All of these claims linking Britain to stories from the Bible, featuring ancient visitors from the Near East carrying sacred and powerful relics, are dubious in the extreme, but interestingly, they are not alone. These arguments echo another story, popular in the Middle Ages, which has entered modern myth today and continues to be believed by some who see in it a hidden historical truth, despite the fact that it was introduced through the fanciful legends of the Arthurian literary tradition. There are those, too, who may claim that Arthurian legend was real, but most people accept this body of medieval romances as nothing but fantasy. How strange it is, then, that one motif and thread in the cycle of Arthurian tales, that of the quest for the Holy Grail, is viewed as real by some who even reject the stories in which it appeared. These believers will suggest that the poets who penned Arthurian romances must have incorporated pre-existing traditions about a real Christian relic, or that they were cryptically revealing some hidden truth regarding this artifact, which was far more real than the chivalric adventure stories in which it appeared. These believers, for the most part, contend that what can be trusted in the medieval romances, the kernel of truth at their heart, is that a certain vessel, used by Christ at the Last Supper, was thereafter used to collect his blood when he was crucified, making of Christ’s seemingly metaphorical dinnertime conversation about drinking his blood, the blood of the covenant, into something far more literal, and imbuing the vessel, which would come to be called a “grail,” with some divine power, or at least, significance. Afterward, Joseph of Arimathea, a secret disciple now venerated as a saint, took Christ’s body down from the cross and provided a tomb for his interment. And it is this figure, Joseph of Arimathea, who it is said took this Grail, along with the Holy Lance that pierced Christ’s side on the cross, and traveled with them to ancient Britain, where he became the first Christian Bishop of the British Isles and ensured that these relics would thereafter be protected. Thus it entered Arthurian legend, where the family of Joseph of Arimathea, known as the Grail Family, kept the relics through the ages, their lives supernaturally extended by the taking of the host, or sacrament, from the Grail. Though to many it may seem a silly question to ask, akin to asking what is the historical basis of the Lord of the Rings, the number of later traditions and works of fiction and pseudohistory and conspiracy theory that treat the Holy Grail as if it were real obliges me to determine what, if any, real basis the legend may have in reality.

As you have probably already figured out, if you’ve been reading my blog posts for the last few months, this is yet another of my explorations of the history and the legends that served as the basis of the Indiana Jones films. I’ve been really enjoying digging deeper into these topics and rewatching the films as I look forward to the release of the final, long-awaited film of the series, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. As a MacGuffin for an Indiana Jones film, the Holy Grail seems absolutely perfect. It serves as the Christian counterpart to the Ark of the Covenant, in that it was of divine origin, even containing within it the very power or essence of God, and was capable of performing miracles, by some readings of the source material. In fact, it has even been discussed, in my principal source, The Holy Grail: Imagination and Belief by Richard Barber, as a kind of Christian allegory for the Ark, with Joseph of Arimathea’s wanderings with it representative of the Israelites’ wanderings through the wilderness with the Ark. But more than that, since a MacGuffin is something quested after, the Holy Grail is one of the most famous MacGuffins of all. For Indy to quest after the Grail was for him to take part in a long literary tradition; far more even than the Ark of the Covenant, the idea of undertaking a quest to find or discover the true nature of the Holy Grail has always been a large part of the legend. The nature of what that search meant, however, has evolved with the story through the years. In the later Arthurian romances of Sir Thomas Malory, it became an important part of a solidifying national mythology.

Photo of the Grail and Grail Diary from the third Indian Jones, as displayed at The Hollywood Museum. Image credit: Courtney "Coco" Mault, licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY 2.0)

In another regard, the Holy Grail again certainly seems to have been a perfect MacGuffin, since Nazis were genuinely interested in the legend of Percival, the Arthurian Knight tasked with Questing after the Grail. Just as Arthurian legend became very important to the construction of national identity in Britain, so too it slowly became embraced by Germans and reinvented as a text foundational to their own Teutonic racial identity. This began in the early 19th century, with German Romantics adapting Arthurian legends featuring the Grail, and reached its apogee with the creation of Richard Wagner’s mid-19th-century opera, Parzival. Adolf Hitler was a great admirer of Wagner’s operas and viewed them as an important touchstone for the heroic nationalist myth that he promoted in Nazi Germany, and as Wagner was himself an anti-Semite and racist, his work and the resurgent myths they focused on, including that of the Holy Grail, became a major element of Nazi identity. But it should be emphasized that the Nazis were never out searching for the Grail as if it were a real artifact. The Ahnenerbe, about whom I spoke a great deal in my series on Nazi occultism, was actually interested in scholarly evidence of an Aryan precursor race, and hunting down a Christian relic would not have served their purpose. The notion in Last Crusade that the Nazis were after the Grail actually derives from the claim that Hitler was obsessed with another relic of the Crucifixion that was featured in the same Arthurian legend as the Holy Grail: the Holy Lance. This item, also called the Lance of Longinus, had already been mythologized as a kind of supernatural MacGuffin that Hitler was seeking in the 1972 occult book The Spear of Destiny by Trevor Ravenscroft, which was undoubtedly an influence on the Indiana Jones films generally in that it portrayed Hitler as being obsessed with acquiring Jewish and Christian relics. Ravenscroft’s book is a work of pseudohistory, and like the Holy Lance, the legend of the Holy Grail too evolved in more modern times, to be embraced not only as a powerful symbol by Jungian psychoanalysts and New Age enthusiasts, but as a literal object or hidden secret by pseudohistorians and conspiracy theorists who see in its legend a kind of coded treasure hunt. I’ve explored this before, in my blog posts The Priory of Sion and the Quest for the Holy Grail and The Secret of Rennes-le-Château and Abbé Saunière’s Riches, but those were early pieces and narrow in focus. I’ll mention the subject matter of those blog posts again later, and it may be worth revisiting them after reading this. But for this post, the question is of the historicity of Grail Legend.

The very name of the third Indy film, the Last Crusade, seems to indicate some genuine historicity to the legend of the Grail, because unlike the Grail quests of Arthurian legend, the Crusades were real historical events. Indeed, some who have viewed the Indiana Jones film but lack further historical knowledge may mistakenly believe that the Crusades were about searching for the Holy Grail. That is not the case at all. The Crusades were a series of religious wars waged between Christendom and the Islamic world, starting in the 11th century, when the Byzantine Emperor asked the Pope for military aid against the Turks, and the Pope in response mustered the Christian nobility of Western Europe to march on the Holy Land and occupy Jerusalem for Christianity. In fact, the launching of the Third Crusade was, in some ways, undertaken to recover a supposed relic of the Crucifixion. The kings of the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem had long held a fragment of wood supposed to be a piece of the True Cross, and their armies carried it with them into battle. When Saladin defeated crusader forces in 1187, that piece of the True Cross fell into Muslim hands, and many European preachers urged the launching of another crusade to recover it. It was exactly during this period, when the idea of the recovery of a relic of the Crucifixion was being used to encourage further crusades, that the first Arthurian romance featuring the Holy Grail was composed, in France, or more specifically Flanders, by a poet named Chrétien de Troyes. Here we find the only further potential connection between the Grail and the Crusades, in that the poet Chrétien de Troyes dedicated his works to his patron, Philip of Alsace, Count of Flanders, who had participated in the failed Second Crusade. Thus it is entirely possible that Chrétien de Troyes introduced the element of a quest for a relic of the crucifixion animating the knights of his chivalric romance as a kind of propaganda for further crusades.

1933 German postage featuring the Parsifal and the Holy Grail.

In the Last Crusade, the legends of King Arthur are only mentioned in an offhand way, dismissed as fairytales, yet the Grail is presented as a historical object, which of course has misled many fans of the film who know little else about the legend besides what the film portrays, to believe it was a real object. The question of whether or not it was real, however, may be simply answered. The Holy Grail was a purely literary tradition. And it appears to have been invented by Chrétien de Troyes between 1181 and 1190. In his work, The Story of the Grail, also called Perceval, we are introduced to the young knight of Arthur’s Round Table, Perceval, who encounters a king out fishing on a river, the Fisher King, who invites Perceval to his castle. At the castle, Perceval witnesses a strange procession, which includes a man bearing a bleeding lance and a woman carrying a fine, expensive-looking “grail.” Perceval, who had been taught not to speak out of turn, says nothing, and later is admonished for not having asked about the grail and whom it “served.” Beyond this, as Chrétien de Troye’s work was unfinished, little more is said of the Grail and its history or nature, except that it contained a piece of sacramental bread that kept the Fisher King alive. Interestingly, most elements of the legend are not clearly established in the work. The grail is not identified as being a relic of the crucifixion or even being a sacred relic at all. In fact, by de Troyes’s description it was to be seen more as a “rich grail” than a holy one. The notion of its holiness was not really established until the “continuations” of de Troyes’s work, when a series of poets, some anonymous, attempted to further his work, or complete it, during the following 20 years. In the first of these, the author suddenly uses the full title, calling it the Holy Grail, as if this had already been established. However, scholars analyzing the language of these continuations have determined that they must have been written by French poets of the same region, who may even have served the same patron, raising the possibility that they knew something of de Troyes’s intentions and where he was headed with the story. There are some elements of de Troyes’s original work that do hint at the eventual direction the continuations and later derivative works would take. The grail is said to hold a special host wafer that extends the Fisher King’s life, thus clearly connecting it with the Christian ritual said to have first been established by Christ at the Last Supper. And indeed, the leading question, the secret of whom the Grail served, seems to have clearly been a setup for a later reveal that it had served Christ, in that it was used at the Last Supper. Lastly, de Troyes’s portrayal of the bleeding lance can only be interpreted as a depiction of the Holy Lance, which was typically described as having blood running down it. It seems pretty evident that de Troyes was indeed heading in the direction that later writers eventually took the story. But this has led some to suggest that he wasn’t actually inventing the story, that he was actually retelling an ancient tale. Chrétien de Troyes himself speaks of a source book that his patron gave him, but from the way he refers to it only vaguely, this seems to only be a literary device. Later scholars have suggested that Arthurian legends such as Percival’s were derived from ancient Celtic legends as seen in texts such as the Mabinogion, and the argument is convincing for some other Arthurian legends, but no clear connection can be discerned with the story of the Grail. Still, though, as we will see, there may have been some pre-existing tradition that inspired Chrétien de Troyes as well as those who continued his work.

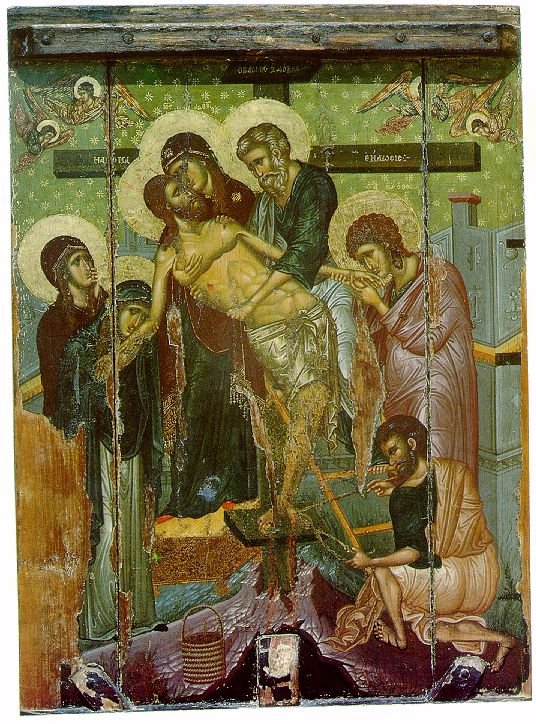

Among the French poets who expanded on the work of Chrétien de Troyes, the man most responsible for the creation of the Holy Grail myth as we know it today was Robert de Boron, writing about a century later. It was de Boron who revealed the nature of the Grail as being a Crucifixion relic, and it was he who developed the supposed history behind it, telling of Joseph of Arimathea’s involvement and thereby giving the entire legend a biblical cast. But the actual biblical basis for this Christian dimension to the story may surprise some. In reality, there is no scriptural basis to the story whatsoever. The extent of the scriptural evidence is only the existence of Joseph of Arimathea. This figure does appear to have existed, based on his presence in multiple gospels as one of the men who takes Christ’s body down and prepares it for burial. The notion that Joseph of Arimathea may have been a member of the Sanhedrin appears to have derived from his association with Nicodemus, a Pharisee who is clearly stated to have been a member of that assembly of rabbis and who in the Gospel of John helps Joseph of Arimathea prepare the body. Interestingly, pretty much everything about Joseph of Arimathea from Robert de Boron’s work appears to have been cribbed not from the canonical scriptures, but from the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, which I have mentioned before in a few episodes. In that work, Joseph of Arimathea is arrested and imprisoned after placing Christ in his tomb, but when they open his cell to kill him, they find he has disappeared. When Joseph is eventually found, he says that Christ visited him in his cell and released him. What de Boron added was that Christ brought with him the chalice from which he drank during the Last Supper, which had earlier been used to collect his blood on the cross, and commanded Joseph to keep it safe, whereupon Joseph took it away to ancient Britain. Such a journey would of course have been extremely arduous and unlikely, and it’s unclear why Joseph would choose Britain of all places. But this may not have occurred to de Boron as being unbelievable in the 12th century. A hundred years after Chrétien de Troyes seems to have invented the Grail, and hinted about its secrets, Robert de Boron incorporated apocrypha to flesh out that secret. And he may also have been weaving in an older tradition that could possibly have inspired de Troyes himself, as in my principal source, The Holy Grail: Imagination and Belief, Richard Barber reveals that there existed an iconographic motif in artwork depicting the crucifixion that shows figures standing beside the cross and catching Christ’s spilled blood in a chalice. Some examples of this iconography predate the work of Chrétien de Troyes by nearly 300 years. This certainly seems to be the origin of Robert de Boron’s conception of the Holy Grail as both the chalice used by Christ at the Last Supper and the cup that caught his blood. There is a problem, however, with the idea that this iconography inspired Chretien de Troyes’ original invention of the Grail, though, as in its original form, it appears this thing called the “grail” was never meant to be a chalice or cup at all.

The Achievement of the Grail, a 19th-century tapestry depicting the end of Perceval’s quest after the Grail.

Many assume that the word “grail” means cup or chalice and always has, but that is not the case. The meaning and etymology of the word “grail,” or graal in the Old French as used by Chrétien de Troyes, is unclear. Some think that it derived from the Latin cratis, for woven basket, and that this evolved to mean other kinds of vessels and receptacles. Most however think that it derives from the Latin gradale, signifying some kind of dish or cup. Those in the cup camp see the Latin word as having derived from an earlier Greek word, krater, for a cup with two handles, but it may have derived from the Latin garalis, which was a dish that Romans used to serve fish. Indeed, all signs in the original Grail text by Chrétien de Troyes point to the word being used to refer to a shallow dish from which meat would be served in a sauce. At one point, when a hermit further teases Perceval with the secret of what the graal contained before revealing that it held the Eucharistic bread, he tells him that it did not have in it “a pike or lamprey or salmon,” which would be absurd things to place in a chalice. Its use in other vernacular texts in the south of France confirm this, and we even have the words of one Cistercian monk of Froidmont who in 1220 explicitly identifies the word grail with the Latin gradale and furthermore states that “[g]radalis or gradale in French means a broad dish, not very deep, in which precious meats in their juice are customarily served to the rich.” Thus, the Grail, if de Troyes originally meant it to be related to the Last Supper at all, can only be viewed as the platter from which Christ and his disciples were served. It appears only later to have been confused with, or combined with, the chalice often depicted in art as having caught Christ’s blood, which may actually be meant to depict a different cup altogether, not one that he drank from at the Last Supper, but one that the Roman soldiers used at Golgotha when offering Jesus a drink of vinegar and gall just before crucifying him.

Beyond this misreading of the source, which resulted in the invention of a holy chalice, there have been other misreadings, the most famous of which being that the Old French phrase san graal, or Holy Grail, was actually intended to be parsed with the “g” at the end of the first word, making sang raal, or sang réal, meaning “royal blood.” This was, of course, popularized by Michael Baigent, Henry Lincoln, and Richard Leigh in their bestselling 1982 work of conspiracist pseudohistory, The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, which claimed that the Holy Grail really was a coded tradition referring to the progeny of Christ and Mary Magdelene, who had traveled to the south of France and founded the Merovingian dynasty. This refuted claim was afterward further propagated by Dan Brown in his blockbuster novel and film The Da Vinci Code. Again, check out my post The Priory of Sion and the Quest for the Holy Grail to read more about the flaws with their theories and how they were actually the victims of an elaborate hoax. Here it is more relevant to focus on the fact that they were not the first to misread the source material in this way. In the 15th century, an English contemporary of Thomas Malory, John Hardyng, was the first to misread the Grail texts in this way, and in his work, the secret of the Grail leads Galahad to undertake a crusade and set himself up as a king over the Saracens, to “achieve” royal blood, as it were. Nevertheless, Hardyng’s interpretation of the term, which has been expanded upon ad nauseum, was incorrect from the start. In the original Grail text, Chrétien de Troyes never even called it a “Holy Grail,” thus there was no such phrase to be parsed. The closest he came was when he says tant sainte chose est li graal, or “so holy is the grail,” likely because it held the Eucharistic host that prolonged the Fisher King’s life. But this phrase can in no way be parsed to fit the “royal blood” interpretation, unless de Troyes meant, despite many spelling errors, to nonsensically write, “so bloody is the royal.” And even if you accept the later continuations as canon and believe they were truly finishing the story de Troyes intended to write, the Grail is never associated with blood as the lance is. It holds a communion wafer. In the later extrapolations of Robert de Boron, certainly it is said to have caught Christ’s blood, but we have seen this story was an adaptation of the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, which also contains no mention of any vessel catching Christ’s blood.

Byzantine art depicting Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus taking Christ’s body from the cross.

Beyond these misreadings, however, there were also further reimaginings of the nature of the Grail throughout its numerous literary treatments. For example it was at one point viewed as a book, written in blood by Jesus himself, kind of the ultimate Gospel written by the man himself. This interpretation appears to have been invented as the framing story of a thirteenth century French poem called the “Grand St. Graal,” in which Christ is said to have appeared to a hermit in the 7th century and given him the book, which contained the history of the Holy Grail, and making it clear that holding the book itself conferred the same effect as holding the Grail. Another reinvented version of the Grail comes from 13th-century German knight and epic poet Wolfram von Eschenbach, who in his work Parzival reveals the Grail to be a stone. In fact, when this is revealed, it seems more like a revelation of what the Grail holds, the thing which extends life, not the host here but a stone which can prolong youth and extend life, which is called lapsit exillis. This description of it as a stone that confers long life would, of course, cause alchemists to view von Eschenbach’s work as yet another coded hint regarding the Philosopher’s Stone, and it does make sense for alchemists to equate the Grail with the object of their perennial quest, which may be used to create an elixir of life. Indeed, they read von Eschenbach, and they suggested, much like the san graal/sang real misreading, that he must have written it incorrectly, because lapsit exillis means nothing in Latin. They will say that he must have meant lapis, which means stone, and that perhaps he meant the “stone of elixir,” or maybe lapis exilii, the stone of exile, or lapis ex celis, the stone from heaven, or even lapsavit ex celis, meaning “it fell from heaven.” This last view of von Eschenbach’s Grail stone has even led some to identify it with the Black Stone of the Ka’aba, thought to be a meteorite, about which I spoke in depth in my last patron exclusive minisode. The simple and disappointing truth of the matter, though, is that Wolfram von Eschenbach was, by his own admission, illiterate, his poems taken down by dictation. Likely he just made up a Latin-sounding term with no deeper meaning and most probably got the idea that the Grail contained a precious stone from a misunderstanding of Chrétien de Troyes, who described the Grail as made “of fine, pure gold; and in it were set precious stones of many kinds.” The truth that should be emerging here is that no one, not even the earliest of the poets who wrote about it, had a clear conception of what the Holy Grail should be, and so they just made stuff up.

Nevertheless, these disparate notions of the Holy Grail did eventually cohere, and the myth became so widespread and such a part of the medieval zeitgeist that real physical chalices began to crop up and be claimed as the genuine article. One is the Sacro Catino, or Sacred Basin, held at Genoa Cathedral. Another is the Holy Chalice of Valencia, an agate bowl mounted in such a way as it can be used as a chalice, which is kept at Valencia Cathedral. It is worth noting that the provenance of both of these relics cannot be confirmed to precede the grail romances, thus making it quite apparent that they were claimed to be the Holy Grail only after the literary tradition had become popular. This has not kept them from receiving some official recognition by popes, though, they have refrained from officially recognizing the relics as the actual cup of Christ. And there is even a contender in New York City, at the Met! The very fact that there are competing relics that only appeared after the birth of the legend goes to show that they are all most likely cases of pious fraud. The term pious fraud is used to refer to deception, such as the counterfeiting of miracles, meant to increase faith, with the idea that the ends justify the means, but in this context, we refer to the phenomenon of churches claiming to have sacred relics in order to bolster attendance and encourage pilgrimage for the principal purpose of boosting their earnings. Indeed, it appears that a chalice said to have been used by Christ at the Last Supper, along with a lance said to be the Holy Lance, was being displayed and drawing pilgrims from the British Isles to Palestine as far back as the 7th century, another possible origin for the legends, but likely also another case of pious fraud. I’ve spoken about this phenomenon before, most recently when I pointed out the any church that had possession of the actual Ark of the Covenant likely would not have kept it a secret, and more specifically when exploring objects such as the Veil of Veronica, the Guadalupe Tilma, and the Turin Shroud.

The Holy Chalice of Valencia

The legend or myth of the Holy Grail survives today not only in Italian and Spanish Cathedrals, but in fiction, in novels and films and television, and it has maintained the interest of readers and viewers because of the inventions of conspiracy speculators who have further mythologized the Holy Grail as a secret kept hidden by shadowy secret societies, and especially the Knights Templar. As we saw with the Ark of the Covenant, the Knights Templar, or the Order of Solomon’s Temple, were a Catholic military order organized to protect pilgrims to the Holy Land during the Crusades, and they became a wealthy financial institution as well, forming a kind of proto-multinational banking system. In 1307, the order was suppressed by King Philip IV of France, who was indebted to them and leveraged rumors that they worshipped the devil in order to wipe them out and seize their wealth. The Knights Templar certainly kept a hoard of valuable items in their treasury, all of which was seized by the French crown, and the notion that they had acquired some religiously significant relics from the Holy Land seems believable enough, but history tells us that the treasure seized by King Philip was in part composed of coin, but was predominately in the form of land. Any valuable items that they held were being stored for clients, who deposited them with the order for safekeeping, since the knights could better protect them. Again, they were essentially a banking organization. There is no evidence that they dug up the Temple Mount and carried the Ark of the Covenant to France, and there is even less reason to believe that they had a real Holy Grail in their possession. First of all, we have no reason to believe that the Holy Grail actually existed, and if we think of it only as the cup used at the Last Supper, or the cup of vinegar and gall served to Christ on Golgotha, or simply as whatever early pious fraud was being displayed in Palestine as such a cup back in the 7th century, we have no reason to think it was kept at the Temple Mount by Muslims before Crusaders sacked it, or that it had been buried there centuries earlier, as is the legend of the Ark. But more than this, the timeline simply does not make sense. The very beginning of the idea of the Holy Grail began in the 1180s, when Chretien de Troyes wrote his poem, and the first concrete sense of the Grail as holy relic would not arrive until the First Continuation of his poem years later. Whereas the Templars were founded around 1120. If the Templars were indeed founded in order to protect the Holy Grail, as the legend would eventually claim, why was there no sense of this in the original lore? In the first Grail romances, it is protected by the Grail Family of the Fisher King, and when Robert de Boron fleshed out the myth in his 13th century adaptation, he has Joseph of Arimathea taking it out of the Holy Land long before the Templars ever existed. Thus, if we are to believe the Templars discovered it in Palestine, then we cannot believe the rest of the background about its relevance to the crucifixion story.

In fact, the first explicit connection of the Templars to the Grail legend seems not to have arisen until a hundred years or so after they were stamped out in France, in John Hardyng’s Chronicle, as he claimed that, when the fictitious Galahad learned the Grail secret and set out on Crusade to “achieve royal blood” and set himself up as a King in the Holy Land, he founded an order of knights, the order of the royal blood, based on Arthur’s Round Table, and the Templars, he said, were thereafter founded and modeled after them, and the Hospitallers after them in the same fashion. It was a clear attempt to draw some parallel between Catholic military orders and Arthur’s knights, and it probably doesn’t need to be said that Galahad and his order of the Holy Grail never really existed. This first explicit link between the Templars and the Grail is tenuous at best. Most conspiracists who are looking for a stronger link go back to the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach, he who imagined the Grail to be a magical stone, for in his work Parzival, he mentions that, while the Grail was entrusted to a certain dynasty, it was kept at a certain temple, rather than in a castle as the previous romances had depicted, and he uses a certain word, templeise or templeisen, for the keepers of the Grail. It has been argued that Eschenbach actually meant Templar, but there is little reason to believe this. The Templars were not well-known in Germany at the time von Eschenbach was writing, and according to his description, there were women among these templeisen who took care of the Grail, which seems to make it quite clear that it wasn’t a fraternal order of knights he was describing. And it must be remembered that Wolfram von Eschenbach was illiterate, or at least said himself that he could neither read nor write. So like his faux-Latin term for the Grail, lapsit exillis, it seems likely that his templeise was just another nonce word, a fictional name for a fictional group, and Templar conspiracists have since read into it, seeing what they want to see. And that is an apt explanation of all the Grail lore, from the authors of the Continuations who imagined a more sacred nature of the Grail, to Robert de Boron who connected it to the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, to Thomas Malory and John Hardyng who used Arthurian legend to reflect 15th-century English politics, and on from there, with, as we’ve discussed, ideas of German nationalism inspired by Wolfram von Eschenbach’s work and themes of spiritual and psychological significance found by New Agers and Jungian writers and conspiracy speculators assembling elaborate pseudohistories based on questionable readings of medieval poetry. In this way, the Quest for the Grail, as a quest for knowledge or understanding, is quite real, even if the secrets revealed at its conclusion may be, like the sources of the myth, more fantasy than fact.

*

Until next time, remember, it may seem silly that some have treated works of fiction like The Da Vinci Code as if they are reliable sources of accurate history, but we see that ancient works of fiction like the Grail romances have long been mistakenly treated like historical records, resulting today supposed non-fiction works of pseudohistory like The Spear of Destiny and The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, which inspire movies like the Indiana Jones films and novels like The Da Vinci Code. It’s all simply part of the mythologizing of our past, and you have to look past the adventure stories and deeper into history to see through it.

Further Reading

Barber, Richard. The Holy Grail: Imagination and Belief. Harvard University Press, 2005.

Callahan, Tim. “Holy Relics, Holy Places, Wholly Fiction.” Skeptic, 13 Sep. 2022, https://www.skeptic.com/reading_room/holy-relics-holy-places-wholly-fiction/

Goodrich, Norma Lorre. The Holy Grail. HarperCollins, 1992. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780060922047/mode/2up

Nickell, Joe. Relics of the Christ. University of Kentucky Press, 2007.