The Business Plot - Part Two: The Bankers Gold Group

Much like the phrase “fake news,” “fascist” is an adjective that has been diluted through overuse as a political barb. It has become synonymous with “totalitarian” and “authoritarian” in accusations of dictatorial overreach. It is lobbed by those on the right against leftists about as much as it is by those on the left against far-right extremists, such as those who originally coined the term. Fascism as a political ideology sprang up in 1915 Italy when Benito Mussolini, formerly a journalist and politician, abandoned Socialism for nationalism and founded a paramilitary organization to fight in the first world war. Afterward, his fascists, so-called after the fasce or bundle of sticks that is stronger when bound together, turned their violence against what he saw as the remaining threat to Italy, socialists. After strong-arming King Victor Emmanuel III into surrendering the country’s government to his dictatorial control, Mussolini assigned great importance to propaganda. As a former journalist, he knew that he had to exert absolute control over the press in order to maintain his authority. And it was not only Italian journalism he sought to influence with regard to how his regime was portrayed. He felt it important to export propaganda as well. One country in which his propaganda efforts had been quite successful was the United States of America. As the Great Depression worsened, many Americans came to believe that what the country needed was a “strongman” leader like Il Duce, as Mussolini was called. This sentiment was especially strong among the wealthy, who greatly feared a Communist revolution in their troubled times. They lapped up the image of Italian Fascists as patriots fighting a socialist threat and of Mussolini himself as a hero who saved his country from ineffective parliamentary rule and ensured prosperity even in the midst of economic calamity. This portrait of Mussolini, which turned a blind eye to the domestic terror campaigns of his so-called “action squads,” made many a Wall Street financier and conservative politician into self-avowed Fascists back before the world had learned to recoil from the word. In the summer of 1932, in fact, as FDR and Hoover vied for the presidency, Republican U.S. Senator David Aiken Reed stood in the Capitol and unashamedly stated, “I do not often envy other countries and their governments, but I say that if this country ever needed a Mussolini, it needs one now.” The capitalists openly admiring Fascism in those years had been swayed not always by firsthand observation of the goings-on in Italy, but rather by the American press, which had taken part in Mussolini’s propaganda efforts with alacrity, some even accepting payment to do so. Perhaps the most influential of these was William Randolph Hearst, a newspaper mogul and no stranger to using his media empire to influence politics. Starting in the late ‘20s, Hearst actually ran columns written by Benito Mussolini on a regular basis, just as later he would print columns penned by Nazis like Goebbels, Goering, and even Hitler himself! Nor was Hearst alone in his amplification of Fascist propaganda. Richard Washburn Child, editor of The Saturday Evening Post, took money from Mussolini and served as the editor of the dictator’s memoirs, which he also published. And esteemed New York Times foreign correspondent Anne O’Hare McCormick wrote glowing accounts of Mussolini’s charisma and his efficient regime, purposely not reporting on its brutality or corruption. And this is to say nothing of Fascism’s boosters in other industries, such as those on Wall Street, like Thomas Lamont, a partner at J. P. Morgan and frequent economic advisor to the Hoover White House who accepted $100 million from Mussolini and described himself as “a missionary” for Fascism, using all his considerable influence to push America toward a Fascist future. This distinct faction of American high society was on the lookout for the rise of our own potential Fascist leader, whom they called “the man on the white horse,” a savior figure ironically named after one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse associated with war and the end of days. And if Franklin Delano Roosevelt did not turn out to be the dictator they wanted, they thought they just might have to follow the example of Mussolini, who had seized power by marching his paramilitary army on Rome and demanding the king’s resignation.

As mentioned in Part One of this series, many among Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s own patrician class hoped, despite his campaign rhetoric and progressive promises, that FDR might turn out to be the American Mussolini. After all, Mussolini himself had begun as a socialist before turning right. Indeed, William Randolph Hearst, who had not previously supported Roosevelt, later threw the weight of his media machine behind the president elect and even produced a Hollywood feature that was little more than a propaganda piece promoting the idea of a president who would do the country good by turning despotic. The film was entitled Gabriel Over the White House, and it depicted a president who is visited by the Archangel Gabriel and the ghost of Abraham Lincoln after a car accident. Thus divinely inspired, he goes on to seize dictatorial control of the U.S. government in order to accomplish his benevolent agenda. Roosevelt himself encouraged the propaganda, hoping to soften the shock when he sought unprecedented emergency powers after his inauguration. However, as I discussed in part one, regardless of one’s view of the executive and legislative power that FDR wielded during his first hundred days and afterward, what he used it to do, specifically bringing an end to the gold standard and demonizing the rich for gold hoarding, caused the Fascist fanboys on Wall Street as well as in the press to turn on him. And these were not the only reasons they had for giving up hope that FDR was their yearned for “man on the white horse.” Planters in the South and sweatshop operators in the North complained that their mistreated workers were leaving them for jobs created by Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, and industrialists bemoaned the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act in June of 1933, which regulated wages and protected the collective bargaining rights of labor unions. The admirers of Italian Fascism had imagined their strongman leader would likewise favor corporatism over labor interests, and when Roosevelt did not, they thought they smelled socialism, or worse, the dreaded Communism. Later that year, when Roosevelt recognized the Soviet Union diplomatically, exchanging embassies with them, these critics who would have welcomed a Fascist coup declared that FDR was an outright Bolshevik actively transforming America into a Communist nation. Among many of these same critics, the activities of Eleanor Roosevelt also represented an affront to the American way. After her husband had basically invented the modern White House press conference, the First Lady began holding her own and insisting that only female journalists attend. She was an activist for women’s equality, and perhaps even more unforgiveable to the enemies arraying against her husband, she publicly declared that Fascism was a far more pressing danger to the world than Communism.

As I have discussed before, the Bolshevik revolution and the spread of Communism generally has always been associated with the conspiracy delusion and lie about a Jewish world domination plot. This destructive falsehood can most directly be attributed to the plagiarized forgery The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, which alleged that international Jewish financiers led the nonexistent conspiracy to control all nations and people. Thus, even though FDR was making enemies of bankers and financiers, since he had formerly palled around with them, and since he was initiating social reforms that looked a lot like redistribution of wealth, and more specifically because he had begun official relations with Soviet Russia, the critics of FDR folded anti-Semitic conspiracy speculations into their attacks on his administration. Taking America off the gold standard became, in the eyes of the paranoid and hateful, a scheme to give Jews control of all the gold in the world. Anti-Semites scrutinized Roosevelt’s appointees and used math to argue that the President favored Jews. Only 15% of Roosevelt’s appointments were Jewish, but anti-Semites argued that this was out of proportion to America’s Jewish population, which comprised only 3% of its total. One wonders if these individuals would have accepted the logical extrapolation of their own argument, that Roosevelt’s appointments should have matched national demographics in this way, which would have meant some 10% of his appointments should have been Black. But of course, we know they would have been against this, for as Eleanor Roosevelt observed, critics of the New Deal, and especially those anti-Semitic critics who called it the “Jew Deal,” were overwhelmingly against ameliorating the condition of Black Americans. As context, it must be remembered that Hitler and his Nazis were coming into power in Germany at the time, spreading a pernicious racialist political ideology. While many Americans admired and supported Mussolini, fewer knew what to make of Hitler, whose chancellorship was officially ratified the day after FDR’s inauguration. Even as reports of Nazi book burnings and violence against Jews filtered into the U.S., many believed him simply a peculiarity and a European problem, though the First Lady collected newspaper clippings on him, recognizing the global threat he represented. As Nazism metastasized abroad, in America, anti-Semitic conspiracy delusions involving the Roosevelt administration spread as well. In something like the Birther conspiracy claims spread by Trump about Barack Obama, leaflets were printed and circulated depicting the Roosevelt family tree and tracing his lineage back to a Dutch family then called “Rosenvelt” in Holland. This family tree was accompanied by speculation tracing that Dutch family through numerous name changes, Rosenthals, Rosenblums, Rosenbergs, back, allegedly, to a supposedly Jewish family called Rossacampo that had been expelled from Spain in the 17th century. This conspiracy claim relied on the idea that this Jewish family took the Dutch name Van Rosenvelt, which means “of a rose field,” but of course, FDR could just as well have been descended from Dutch Van Rosenvelts. FDR himself traced his family back only as far as Dutch immigrants to America, and was very open, in a letter replying to a Jewish newspaper editor who had inquired about the rumors, that he didn’t really care if he was Jewish, writing, “In the dim distant past they may have been Jews or Catholics or Protestants. What I am more interested in is whether they were good citizens and believers in God.” And of course, whether or not Roosevelt had Jewish ancestry still proves nothing about any involvement in a global conspiracy, let alone that such a conspiracy existed, but since leaflets depicting the Roosevelt family tree were often accompanied by pamphlet reproductions of The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, the anti-Semitic propaganda went a long way toward stirring up populist resentment against the President.

The growing Fascist sympathizers and converts in America, unsurprisingly, looked to what Mussolini had done in Italy, and what Hitler was now also doing, and took notes. One major commonality was the use by these dictators of paramilitary organizations to build power and seize control. Mussolini had his Voluntary Militia for National Security, known as Blackshirts for their customary attire, and Hitler, following suit, had his stormtroopers, known as Brownshirts. The authenticity of the Fascist threat in America can likewise be discerned by the appearance of numerous such paramilitary armies in the U.S. One of them, formed by Ku Klux Klansmen in Georgia, simply called themselves Blackshirts as well, while others differentiated themselves, but only by the colors of their shirts. Tennessee had their Christian extremist White Shirts, bent on taking over local government, and New York had their Gray Shirts, whose focus was removing leftists from teaching positions. Metaphysical writer, Christian nationalist, and Fascist William Dudley Pelley was among those who pushed the conspiracy claim that FDR was secretly Jewish, and he founded the Silver Shirts, a massive militia active in most states that stockpiled weapons and even stole rifles from a California naval airbase. Then there were the Khaki Shirts. Among the Bonus Army had been one fascistic leader, Walter Waters, who after General MacArthur’s destruction of their Hooverville had tried to form his own Fascist army, which he called the Khaki Shirts, but his fellow veterans were mostly uninterested, and his efforts fell apart quickly, such that the Khaki Shirts were not even involved in the next Bonus march on Washington. However, in 1933, one vet, Arthur Smith, reinvigorated the Khaki Shirts as an openly Fascist paramilitary organization with avowed intentions to overthrow Roosevelt, seize control of Washington, and even to “kill all the Jews in the United States.” Smith called himself a general and claimed he commanded 1.5 million men. However, it appears his movement was never that widespread, and during the summer following Roosevelt’s first 100 days, Philadelphia police arrested all of them for alleged plans to storm a National Guard arsenal. The Khaki Shirts collapsed after Smith held a rally in New York attempting to organize another march on Washington and anti-fascists confronted them, leading to one Khaki Shirt murdering a student counter-protester. Smith would eventually do prison time because of this act of violence, and would afterward abandon the group, absconding with twenty-five grand of their funds. The Khaki Shirts would eventually coalesce with Father Charles Coughlin’s militant Christian Front organization. As context for the astounding revelations of the Business Plot, however, suffice it to say that America was no stranger to Fascist movements bent on overthrowing the democratic order and marching on Washington to force Roosevelt’s resignation, and at least some of them were inspired by or grew out of the legitimate and overall peaceful protest of the Bonus Army marchers. And in response to this fascist groundswell, one Democratic representative from New York, Samuel Dickstein, who had witnessed violence erupting against his fellow Jews firsthand, convinced Congress to organize the House Un-American Activities Committee, or McCormack-Dickstein Committee, specifically with a mandate to investigate Nazi propaganda and fascist threats in the U.S.

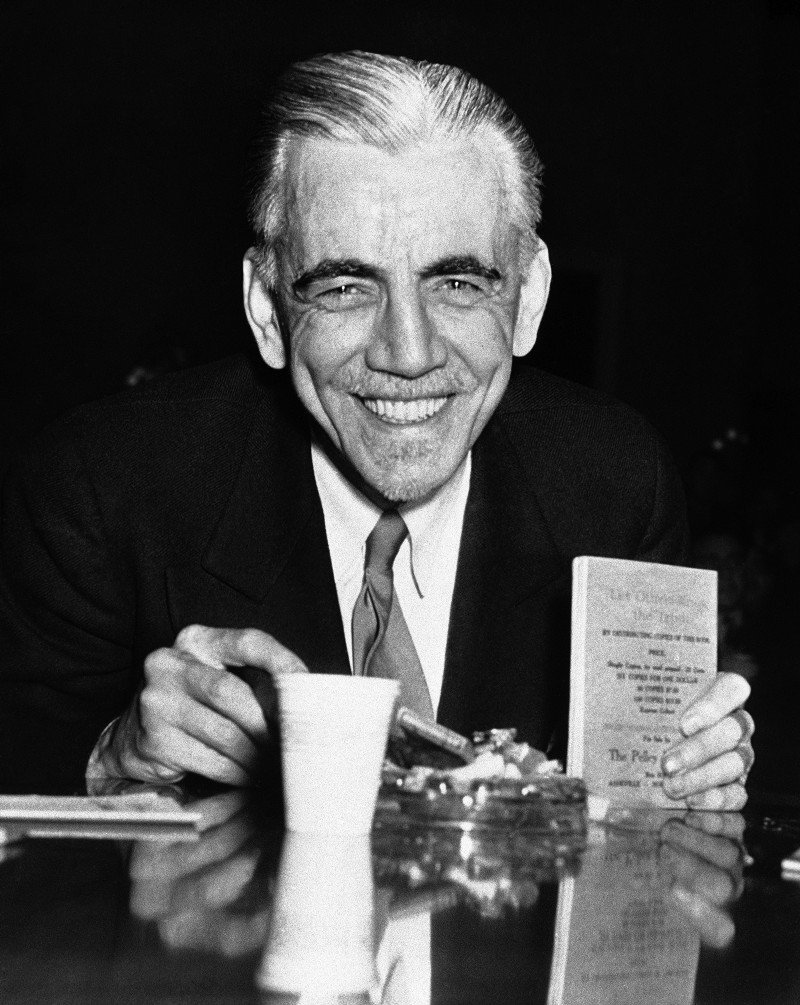

William Dudley Pelley, leader of the fascist Silver Shirts.

This was the state of the country when Smedley Darlington Butler, the retired soldier’s general and veterans affairs activist who had supported Roosevelt and encouraged the Bonus marchers, received an odd visit at his Pennsylvania home from some strange men claiming to be wounded veterans, as he would later testify. One of these callers was William Doyle, and the other a bonds salesman named Gerald MacGuire, or Jerry MacGuire, if you like. Butler was immediately skeptical of the men because they arrived in a limo and sported expensive bespoke suits. They represented American Legion departments in Massachusetts and Connecticut, they told him, and they’d come, purportedly at the behest of numerous Legionnaires who disliked American Legion leadership and were concerned about Roosevelt’s treatment of veterans, to ask for Butler’s help in reforming the veterans’ organization. Butler was by then a popular public speaker and had been vocally critical of the American Legion, so this part of the men’s proposal, to place him in a leadership position in which he could effect change, interested him. However, he disagreed with their assessment of the President’s treatment of veterans, so he remained cautious, and his suspicions were further aroused, according to his later telling of the story, when MacGuire claimed that the White House had barred them from inviting him as a distinguished guest to an upcoming convention. Butler considered Roosevelt a friend and found the claim hard to believe, making him suspect that MacGuire was trying to plant a seed of enmity between him and the President. MacGuire explained that, in order for Butler to attend the American Legion gathering, he had arranged for him to be falsely credentialed as a Hawaiian delegate, and this was all too much for Butler, who refused to entertain the cloak and dagger scheme and sent the visitors away. MacGuire and Doyle returned with a different plan a month later, suggesting that Butler gather a few hundred Legionnaires--something that would be easy for him to do, considering the esteem in which veterans held him—and bring them to the convention, where they could initiate a cheer demanding that Butler be allowed to speak, at which point Butler could deliver a speech they had prepared for him. Butler protested that veterans couldn’t afford the train fare and lodgings they would need to attend the convention, to which MacGuire responded by whipping out his bank depositor’s book, which showed funds of more than a hundred grand that he said could be used to pay these expenses. That is equivalent to about 2.2 million dollars today. Butler’s suspicions only increased with this boast of exorbitant funding, and he thereafter became convinced that MacGuire was a mere front man for some extremely wealthy interests when he read the speech that had been written for him. He was surprised to find that it was essentially a call for Roosevelt to return to the gold standard so that veterans’ bonuses would not be paid in worthless paper currency. Believing that the average veteran understood and cared little about such matters as the gold standard, Butler carefully pushed MacGuire to reveal the backers of the scheme, and MacGuire assured him that the scheme had nine very wealthy financers, but that he could only reveal two of them: a Wall Street bigwig veteran, Grayson M.P. Murphy, whom Mussoliini himself had awarded an honorary Italian military title, and Robert Sterling Clark, heir to the Singer Sewing Maching fortune, with whom Butler had served and of whom he had a low opinion. When Butler craftily expressed doubt that MacGuire’s venture really was so well-funded, MacGuire responded by producing a stack of thousand dollar bills and offering them to Butler. Keep in mind that in 1933, the thousand dollar bill, a denomination that would be discontinued in 1969, was equivalent to more than 20 grand today. Thus proffering a stack of them would be the same as whipping out a billfold of more than a million bucks. Butler was reportedly aghast and reacted like someone being extorted, telling MacGuire, “You are just trying to get me by the neck,” and ending the conversation abruptly, saying, “I am not going to talk to you any more. You are only an agent. I want some of the principals.”

After his last strange encounter with MacGuire, Butler realized that he should try to collect evidence of whatever was being plotted by MacGuire and his backers, so he began to play along. He wrote to MacGuire, creating a paper trail, pretending to have come around, and requesting a meeting with the Singer heir that MacGuire had named as a backer, Robert Sterling Clark. During that subsequent meeting, Butler expressed his confusion about the contents of the speech the group wanted him to give, and Clark revealed that it had been written by the chief counsel of J. P. Morgan and Company at the behest of Morgan himself. Very quickly, Clark transitioned from talking about how a return to the gold standard would benefit veterans when they receive their bonuses to talking about how it would benefit the wealthy, like himself, outright admitting that he was spending so much of his money to back this scheme because “I have got 30 million dollars and I don’t want to lose it. I am willing to spend half of the 30 million to save the other half.” Finding this attempt to force public policy changes by manipulating veterans entirely distasteful and doubting that Roosevelt would even prove as compliant as the plotters believed, Butler refused to attend the American Legion convention. When it was convened, however, Butler read in the papers that its delegates were swayed by an inundation of telegrams to pass a resolution endorsing a return to the gold standard. Thinking the matter concluded, Butler was surprised when Macguire kept bothering him. For the rest of the year, he repeatedly invited Butler to veterans’ gatherings and offered to pay him to speak about returning to the gold standard, and in 1934, every time Butler arranged a speaking appearance, MacGuire would show up and offer him three times his speaking fee to include some remarks about the gold standard in his speeches. Finally, in the spring of 1934, MacGuire met again with Butler and revealed to him that he had recently been overseas, visiting foreign nations to better learn how Fascist movements used veterans’ organizations to seize control of governments. He explained how he had visited Mussolini’s Italy, Hitler’s Germany, and Stalin’s Russia and discovered that veterans organizations or citizen armies proved to be the “real backbone” of each dictatorship. He didn’t think that Americans would accept such coups as Mussolini and Hitler had conducted with their private armies, but he said he saw in France a perfect model for what he and his backers hoped to achieve in America. On February 6th, 1932, a demonstration of far right nationalist groups turned violent, and due to the involvement of veterans’ organizations, like the anti-Semitic Croix-de-feu, or Cross of Fire, it was dubbed the Veterans’ Riot and viewed as a fascist coup that did not result in a dictatorship but did successfully topple the left-wing government. MacGuire insisted to Butler that the same could be accomplished here in the U.S. if Butler, who had the ear of every soldier, would encourage them to band together and march peacefully on Washington demanding change—a bloodless coup. Moreover, their coup would be entirely constitutional, he assured the increasingly alarmed general. “We have got the newspapers,” he declared, presumably referring to Fascist sympathizer William Randolph Hearst’s papers, “We will start a campaign that the President’s health is failing.” With pressure from the veterans’ armies like that which was previously exerted by the Bonus Expeditionary Forces, MacGuire said that Roosevelt, to ease the burdens of his office, would appoint someone to a new cabinet position, Secretary of General Affairs, who would in effect act as the chief executive, making FDR a mere figurehead. The entire scheme was clearly an imitation of Mussolini’s March on Rome and handling of the King of Italy. If Roosevelt didn’t agree to the arrangement, MacGuire explained, he would be compelled to resign, and one by one each person in the line of succession would decline the office for reasons MacGuire explained with eerie confidence, as if it had already been arranged, until by the laws of the time, the office would pass to their new man in the cabinet, the Secretary of General Affairs, regardless.

Symbol of the fascist Croix-de-Feu veterans organization that MacGuire believed could be emulated to affect a coup in America. Image Credit: Fauntleroy (CC BY-SA 4.0)

As soon as their group, which Butler would thereafter refer to as the Bankers Gold Group, had the reins of government, they would bring back the gold standard, and MacGuire insisted they had all the capital they would need to accomplish their objective, with three million dollars currently available and a total budget of $300 million. According to the worth of today’s dollar, that’s an astonishing $6.7 billion in financing, according to the American Institute for Economic Research’s Cost of Living calculator. Butler played it cool, saying he would need to think further on it, and MacGuire told him that if he read the news, he would soon get a sense of who his powerful backers were, as their superorganization was about to be publicly announced, and “[t]here will be big fellows in it.” Two weeks after those foreboding words, Butler read about the formation of the American Liberty League, an organization founded to protect property rights and bolster free enterprise, which came out the gate swinging at Roosevelt for “fomenting class hatred.” Among the financial supporters of the organization were the two names MacGuire had already given Butler, Grayson M.P. Murphy and Robert Sterling Clark. The rest of the names included conservative Democratic rivals of Roosevelt, Republican opponents, Wall Street royalty, and titans of numerous industries. Some of the more recognizable names present were financier E. F. Hutton, two du Pont brothers who had served as Presidents of the multinational chemical company, and Samuel Colgate, president of the soap company that bore his family name. Executives active in the mining, automotive, oil, and retail industries were listed alongside them, as were more than one of the builders of the Empire State Building. It was a veritable Who’s Who of American business and politics, and according to Butler, it caused him great worry about how he should proceed. Eventually, he decided to contact the press before going to the J. Edgar Hoover or to the President. The editor of the Philadelphia Record assigned investigative journalist Paul French to look into it, and Butler, who misrepresented the reporter as a newspaperman sympathetic to their cause, managed to get MacGuire to agree to speak with him. Astonishingly, MacGuire went ahead and confirmed the entire story to the journalist, including the information about his trip to observe Fascist armies abroad, adding the further tidbit that the du Ponts had arranged to arm their army of veterans with Remington rifles. The reporter quoted MacGuire as saying, unironically, “We need a Fascist government in this country to save the Nation from the communists who want to tear it down.” To cap it off, MacGuire actually told French that the country could easily resolve their unemployment problems by doing what Hitler had done and placing the poor into forced labor camps. Thus armed with journalistic evidence of the plot, Butler finally told MacGuire what he really thought of the plan being enacted by the Bankers Gold Group, or the American Liberty League, as they chose to style themselves, stating, “If you get 500,000 soldiers advocating anything smelling of fascism, I am going to get 500,000 more and lick the hell out of you, and we will have a real war right at home.” He then went, in the fall of 1934, to J. Edgar Hoover with the story. Disappointingly, Hoover claimed there was little his Division of Investigation could do, since there was no federal offense, even though there was clearly a case for sedition, inciting a rebellion or insurrection, and treason, and he had been tasked by Roosevelt himself to look into domestic Fascist threats. Instead, true to form, Hoover used this threat to further seize control of domestic intelligence, leading to the formation of the FBI. He did, however, spread word of the alleged plot around Washington, and soon the House Un-American Activities Committee contacted Butler and his reporter, French, to appear before them and answer some questions.

Paul French published his exposé of the Bankers Gold Group and their Wall Street Putsch two days before the two of them spoke to the committee in a secret executive session, with the headline “$3,000,000 bid for fascist army bared.” The story was picked up by major papers all over the nation, so the proceedings commenced with intense press scrutiny, such that the committee was obliged to assure the papers that they would go public when the revelations of the committee warranted it. In the meanwhile, those implicated by French’s exposé were widely quoted in the press categorically denying the allegations. Grayson M.P. Murphy suggested it was libel, and Robert Sterling Clark only admitted to urging Butler to endorse “sound currency,” which at the time was just another way of saying a return to the gold standard. Meanwhile the committee seemed to have lost steam, calling fewer witnesses than expected, and the “Public Statement on Preliminary Findings” they eventually published was lackluster. It started with a statement that it “has had no evidence before it that would in the slightest degree warrant calling before it” several of the more prominent politicians, military officers, and corporate executives implicated in the testimony. The intention, it seems, was not to give in to sensationalism and to avoid the Inquisition-like practice of acting on hearsay, but the result was that the committee appeared to be saying there was little to the accusations, and to some it seemed a cover-up was underway. However, the rest of their statement, as well as the public hearing that followed, and the official report published months later showed that in fact they had ample evidence of the plot. Not only was Smedley Butler’s testimony corroborated by the reporter Paul French, but they managed to acquire correspondence between MacGuire and his superior, Murphy, showing that he had indeed been studying Fascist military organizations abroad, and they further acquired bank records indicating that MacGuire had been given access to large sums of money for which he could not account. All of this disproved the common defense that it was just idle talk, a “cocktail putsch,” and the fact that MacGuire actually offered the money to Butler further disproves the alternative explanation that MacGuire was actually conning his Wall Street backers, since approaching Butler shows he was earnestly attempting to arrange the coup. However, despite the McCormack-Dickstein committee’s final conclusion that Butler had been truthful and there had been an unsuccessful attempt by wealthy and powerful men to stage a Fascist coup, the committee’s report purposely omitted mention of the American Liberty League and the names of the major plotters, and though they stated their intention to get to the bottom of the matter, their investigation petered out and their House Un-American Activities committee was dissolved until 1938, when under a new chair it turned its attention to Communist Party infiltration. To Smedley Butler, it seemed the committee had shrunk from doing their duty, but as a rumor suggested that President Roosevelt himself had met with the committee and quashed their investigation, and since the plot itself seemed at least to have been thwarted, Butler came away appeased. What proved to be more aggravating than the committee proceedings, however, was the fact that while the Fascist plotters did not have their names dragged through the mud, General Smedley Butler did.

Almost all contemporaneous press coverage of the Business Plot treated the allegations as something laughable, lacking any evidence and manifestly untrue. Time magazine called it a “plot without plotters,” and likened Butler to George Custer for “publicly floundering in so much hot water.” The New York Times asked, “What can we believe? Apparently anything, to judge by the number of people who lend a credulous ear to the story of General Butler’s 500,000 Fascists in buckram marching on Washington to seize the government.” And if a news outlet didn’t play down the story like this, they often as not simply chose not to write about it at all. Perhaps, knowing what we know about the aforementioned Fascist leanings of the American press at the time, it is not surprising that the press treated Butler’s accusations as a farce. If we do not want to view national newspapers as being in on a conspiracy, however, since as I have argued time and again, massive conspiracies simply cannot be credited, we might find other reasons for their doubt. For example, it certainly does seem at first blush that Smedley Butler would have been the worst possible candidate to recruit for such a scheme. I spoke previously about his disillusionment with America’s foreign capitalist adventures and wars of empire, which of course are hallmarks of fascism. And he was a prominent supporter of FDR, even considering himself a friend of the president. More than that, he had recently been in the news for making anti-Mussolini, and thus anti-Fascist, remarks. In 1931, he stated in a speech that a friend of his had been riding with Benito Mussolini in his Fiat when the dictator struck and killed a child, and without stopping, belittled the importance of a single life. To give a sense of how strong the sympathy for Fascism and admiration for Mussolini was at the time, Butler had actually been arrested and almost court-martialed for the remark, something that had not happened to a general since the Civil War. Some contemporaries and historians have suggested that Butler might have lied about this hit-and-run incident to smear Mussolini, since it appeared to be an unsubstantiated rumor, and that this shows he may have also been lying about the Business Plot. However, the friend whose story he had been repeating, Cornelius Vanderbilt IV, eventually corroborated the story in his memoirs, though by his telling Mussolini had not explicitly denigrated the value of a single life, but rather simply told him to “never look back.” After all is said and done, Butler looks like an honest man whose claims were corroborated again and again. For example, another person identified as in on the plot, a national commander of the VFW, likewise denied involvement but confirmed the plot by revealing he had also been approached by “agents of Wall Street” regarding a plan to stage a coup. In fact, rather unbelievably, the very next year, Smedley Butler claimed that Father Charles Coughlin telephoned him, trying to recruit him to lead a paramilitary force in an illegal attempt to overthrow the Mexican government and further suggested that an armed insurrection was being planned in the U.S. as well. It beggars the imagination that, after Butler’s revelation of the Business Plot, Father Coughlin would try to recruit him for another such conspiracy, and some have suggested that it was a hoax on Butler, but Butler also claimed to have evidence that Coughlin’s men in New Jersey had stolen firearms from a U.S. arsenal. Furthermore, Butler himself recognized that his claims would never be believed again and still felt so strongly about it that he chose once more to inform J. Edgar Hoover about the matter, though privately this time, not taking it to the press at all. Whether or not this supposed plot of Coughlin’s was genuine, the allegations were certainly prescient, as we know Father Coughlin did build a paramilitary organization, the Christian Front, and in 1939, numerous New Jersey members were arrested and charged with stealing munitions and conspiring to overthrow the U.S. government.

From another view, the choice of the Bankers Gold Group to bring in Smedley Butler makes perfect sense. Robert Sterling Clark apparently told Butler that he was not their first choice, that in fact, many of the financial backers wanted to approach General Douglas MacArthur with their proposition instead. The fact that they ended up contacting Butler shows that they were following the playbook of other Fascist movements. Clearly Butler, the soldier’s general who was universally admired by veterans, who spoke regularly at veterans’ events, and who had already been critical of the existing leadership of the American Legion, was the perfect person to take control of the organization and lead their army. Vets would remember that Butler had been for their cause when the Bonus Army was in Washington, whereas MacArthur had driven tanks over them. Clearly what was most important, in their mind, was Butler’s ability to muster and inspire and lead the rank-and-file vets, as that was what had brought Mussolini and Hitler into power, as MacGuire had reported from his fact-finding mission in Europe. The downfall of their plan was that they presumed everyone, including Butler, had come to hate Roosevelt as much as they did, and if not, that they could always buy a change of heart and allegiance with stacks of thousand-dollar bills. And just as they misjudged Butler, they also misread public sentiment, much like the January 6th insurrectionists, likewise deluded by propaganda in the news they consumed, misjudged what the nation’s reaction to their storming of the Capitol would be. Just as MacGuire and the Bankers Gold Group modeled their proposed coup on their Fascist and Nazi predecessors, so too the similarities with January 6th are striking. The paramilitary organizations involved this time around, the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys, whom all of America saw Donald Trump personally commanding on national television when he directed them to “stand back, stand by” during the debates, are largely comprised of military veterans. The majority of the Proud Boys indicted on seditious conspiracy are vets, and the trial of Oath Keepers founder Stewart Rhodes revealed how he manipulated veterans into joining their cause. The lesson of the Business Plot remains as important today as it might have been before January 6th, 2021, as chapters of the Proud Boys have surged all over the country since then. And now, in Brazil, we find that Bolsonaro, a Trump admirer and purveyor of similar false claims about voter fraud in Brazil, has encouraged another coup attempt modeled on those that have come before it. The old sentiment that “it can’t happen here” is now so thoroughly refuted that its alternative, “it can happen here,” has become trite. What we must remember is that it has happened here, and we must be prepared for it to happen again.

Until next time, remember, there is a difference between conspiracy speculation, which typically lacks irrefutable evidence and relies on fallacious logic, and actual conspiracies, which do occur. The difference, usually, is that the latter, inevitably, are publicly uncovered and proven to exist. The story of Smedley Butler goes to prove that someone always talks.

Further Reading

Archer, Jules. The Plot to Seize the White House: The Shocking TRUE Story of the Conspiracy to Overthrow FDR. Skyhorse Publishing, 2015.

Denton, Sally. The Plots Against the President: FDR, a Nation in Crisis, and the Rise of the American Right. Bloomsbury Press, 2012.

Galka, Bradley M. The Business Plot in the American Press. 2017. Kansas State University, Master’s Thesis, https://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2097/38255/BradleyGalka2017.pdf.

Katz, Jonathan M. Gangsters of Capitalism. St. Martin’s Press, 2021.