Oswald and the JFK Assassination - Part Three: The Lone Gunman

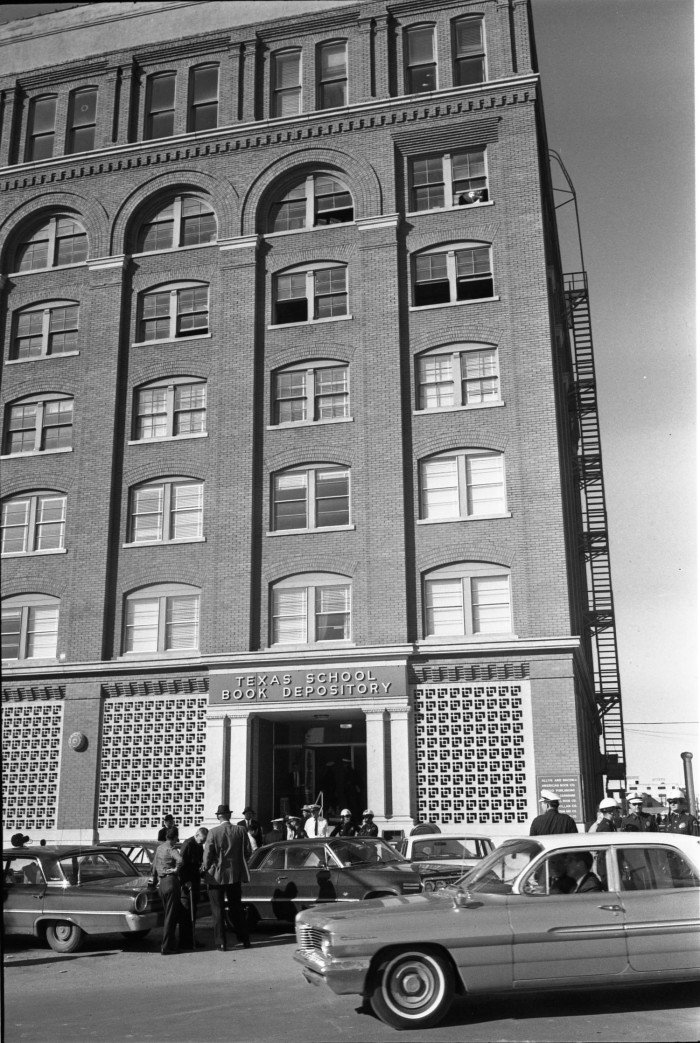

With his wife Marina so near the end of term and ready to deliver their second child, it was determined she should continue to stay with the Paines while Oswald moved into a room at a boarding house closer to Downtown Dallas, where he was searching for work. It worked out well when Oswald, who couldn’t drive and had no vehicle, got the job at the Book Depository, as it was just a 2 mile bus ride from his boarding house. On some weekends, he caught a ride the 27 miles to the Paines’ house to be with Marina. He caught that ride with his new co-worker at the Depository, Buell Frazier, the brother of Ruth Paine’s friend, through whom she had first gotten the lead on the job at the Depository. Marina gave birth to their second daughter in late October, and Oswald saw them at the end of most weeks, otherwise settling into his new job at the Texas School Book Depository, where he was known to sit by himself in the lunchroom and read the day old newspapers. Later the next month, some of those newspapers contained an announcement that President Kennedy’s motorcade would be passing right through Dealey Plaza, smack in front of the Texas School Book Depository. Some conspiracy speculators charge that the motorcade’s route was changed in order to give Oswald his shot at Kennedy, but there is no evidence for this beyond one newspaper misreporting the route, showing a different one that would also have provided a clear shot at Kennedy from the Depository. Regardless of what newspaper Oswald may have read the news in, it’s clear that he did read it and began to hatch a plan, seeing a far more massive opportunity to change history than that which he had attempted to seize in firing his rifle at General Walker. What makes it clear is his behavior during the few days between the news releasing and the day of the assassination. On Thursday, the 21st, the day before Kennedy’s arrival, the notoriously stingy Oswald splurged on a big breakfast, and at work, he asked Buell Frazier to give him a ride to the Paines’ house, an unusual request for a Thursday. He explained it away by saying he needed to fetch some curtain rods from their house for his room at the boarding house, something that his furnished room already had. Sometime before leaving with Frazier, probably using materials present at work, he crafted a long sack by taping together pieces of paper. Marina was surprised to see him that Thursday. He usually called ahead, and he was acting somewhat desperate, trying to kiss her and being more affectionate than usual, saying he missed her and that he “wanted to make peace” with her. Marina brought up the President’s visit, thinking Oswald would relish the opportunity to expound on politics, as he usually did, but Oswald refused to talk about it, claiming he knew nothing about Kennedy’s visit, and remaining quiet through dinner. At some point, Ruth Paine recalled that he had gone out to their garage, where he had stored a bundle that the Paines thought was camping equipment, wrapped up and leaning against a wall, but which Marina knew was his Mannlicher-Carcano rifle. When he left to go back to work the next morning, November 22nd, he left almost his entire savings, $170, on the dresser for Marina, telling her to take as much as she needed and “buy everything.” He also left his wedding ring behind. He walked to Buell Frazier’s house carrying a long, taped up, brown paper parcel, placing it in the back seat of Buell’s car and then simply staring at Buell’s sister in the window to indicate his readiness to leave. It struck her as unusual. When Buell came out and asked what was in the back seat, Oswald said it was the curtain rods he had mentioned previously. Some have tried to claim that Frazier and his sister’s estimation of the length of the package shows that it couldn’t have been Oswald’s rifle, even disassembled. However, curtain rods were never found inside the book Depository, but the Mannlicher-Carcano was, hidden between boxes near a stairwell. Moreover, the package they saw him with that morning, made of brown paper and tape of the kind found in the Depository, and which Buell saw him take into the Depository that day, was the same as an improvised paper bag that would later be found at what appeared to be a sniper’s nest. On the sixth floor of the Depository, which was under construction and almost entirely empty at the time of Kennedy’s arrival because employees had taken their lunch and gone out to watch the passing motorcade, stacks of books had been moved to create a little hiding place by the south-east corner’s window, obscuring anyone’s view of someone standing in that corner looking down on Dealey Plaza. In that makeshift alcove, crime scene investigators found a palm print and a right index fingerprint on boxes, later identified as matching Oswald’s prints. Inside that improvised paper bag found in the sniper’s nest were fibers that matched the blanket that Oswald had kept his rifle in before taking it from the Paines’ garage, and silver nitrate tests would later reveal Oswald’s palm and fingerprints on that bag as well. Along with this evidence were three rifle shells that would later be conclusively proven to have been fired by the Mannlicher-Carcano abandoned elsewhere in the building. That Mannlicher-Carcano was confirmed to be the same rifle Oswald held in the famous backyard photos, as mentioned in Part One, but more than this, a palm print matching Oswald’s was lifted from the stock by Dallas police, and partial fingerprints found on the trigger guard would eventually, through photo enhancements reveal 18 matching points, convincingly identifying them as having been left by Lee Harvey Oswald’s right ring and middle fingers. This evidence alone, from the testimony of Frazier and his sister, the Paines, and Marina, as well as concrete evidence afterward documented by Dallas police, appears conclusive. But those who believe in a conspiracy to murder Kennedy have been determined, through the years, to make this a far more complicated puzzle than it actually is. As the author of one of my principal sources, Vincent Bugliosi, told the Los Angeles Times: “Because of these conspiracy theorists who split hairs and proceeded to split the split hairs, this case has been transformed into the most complex murder case in world history. But, at its core, it’s a simple case.”

Hearing the evidence laid out like this should be convincing—damning, even—but if you have invested your belief in any of the many longstanding conspiracy theories surrounding this case, perhaps because you read a conspiracist book or two, or because you watched the Oliver Stone film JFK, or simply because you have heard too many friends or family members regale you with their secondhand regurgitations of conspiracist reservations, then I’m sure you are already formulating objections. Fingerprint evidence can’t be trusted, you might protest, or, If it was Oswald’s rifle, then of course it would have his prints on it. Notwithstanding the witness testimony that entirely details his efforts to retrieve the rifle himself and smuggle it into the Depository after the newspaper announcements of Kennedy’s motorcade route, those who want to believe Oswald was a patsy will contend that someone planted the rifle and the shells, even though there is no evidence of anyone else entering the Paines’ home and having the chance to fetch the rifle from their garage. Also, a complete frame job, I suppose, would entail knowing which boxes Oswald had recently touched on the 6th floor, so that when they built the sniper’s nest, they could use boxes that had his palm prints on them. And since no mysterious strangers were witnessed by the many book Depository employees that day, it would mean the conspiracy would have to be composed of other employees there. A more feasible conspiracy claim is that Oswald did fire his Mannlicher-Carcano, but that he was not the only shooter that day, that the supposed conspirators allowed him to take his shots but took shots of their own as well to ensure the job was done. This notion, that there were other shooters present, within the book Depository or on the patch of grass between a parking lot and a fence along Elm Street near the railroad overpass—the so-called “grassy knoll”—or elsewhere, has become the central thesis of nearly every conspiracy claim surrounding the JFK assassination. According to these narratives, Oswald may have been a shooter, but he was not the shooter. It’s these claims that we must examine in order to achieve a clear picture of what happened on that chaotic day. But first, let us take a moment to imagine and remember the historic and tragic moment with something approaching respect and sympathy for a beloved life that was lost.

The President’s motorcade, minutes before shots were fired on Dealey Plaza.

At 12:30pm on November 22, 1963, the presidential motorcade turned from Main Street onto Houston Street, to much fanfare. Crowds lined the street, cheering, as John F. Kennedy and his wife Jackie waved. In the convertible limousine’s fold-down jump seats sat Texas Governor John Connally and his wife, also waving to the crowds. In the front seat, driving and riding shotgun, were two Secret Service agents. Kennedy himself had chosen to do away with the plastic bubble top that might have saved his life that day, preferring to have nothing between himself and the gathered people. As usual, all was not as it may have seemed with the President, who presented a public image of great vigor despite personal health struggles. Under his suit, he wore a back brace strapped against his body with ace bandage. Despite any pain or discomfort, though, he also wore a smile as he passed through Dealey Plaza toward the Texas School Book Depository. He had a nice luncheon to look forward to—roast beef. When the first shot rang out, many thought it was a vehicle backfiring, or maybe a firework. But the following gunshots, and the terrible commotion inside the President’s vehicle, made it very apparent what was happening. Dealey Plaza exploded into panic and pandemonium, screams of terror and anger, shouts of confusion, filling the air, ringing through the plaza’s strange acoustics, and echoing, like the gunshots, even today.

Among the claims made to support the idea that Oswald could not have committed this heinous act alone are the claims that he was not a good enough marksman, or that his rifle was not accurate enough, or that its bolt action could not possibly be operated fast enough. It is odd that conspiracist authors have decided Oswald was a terrible marksman when he actually qualified as a sharpshooter with the Marines. The superior officers in charge of the marksmanship branch and Oswald’s training, who actually have some idea of Oswald’s skill with a rifle, Sgt. James Zahm and Major Eugene Anderson, have gone on record as saying Oswald was a fully capable marksman, and more than that, that the shots taken from the Depository were not especially difficult, that it was, in fact, “an easy shot for a man with the equipment he had and his ability.” A marine who served with Oswald, Nelson Delgado, is sometimes quoted as remembering Oswald not hitting his targets, but Delgado didn’t serve with him at the time when he received his marksmanship training and therefore was not an authority on his abilities, as were the officers who trained him. Another tale has it that Oswald came up empty handed on a rabbit hunting trip in Russia, but of course, hunting rabbit is far different than taking a pot shot at a man in a slow-moving convertible, and Oswald’s brother Robert remembered Oswald complaining about that hunting trip, saying his rifle’s firing pin had broken. Robert himself had been hunting with Lee more than once and has stated, “He was a good shot.” So that leaves his equipment, the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle, which conspiracist authors allege is universally condemned as slow and inaccurate and a terrible choice for sharpshooting. Certainly it may not have been the absolute best choice, but Oswald chose it because it was the right price. He clipped a coupon from the magazine American Rifleman to buy it. As for Oswald’s particular Mannlicher-Carcano, when the FBI conducted shooting tests with it, they found it “very accurate.” It had come with a four power telescopic scope already assembled, easily seen in the backyard photos, and the FBI firearms expert who examined it stated that it required hardly any adjustment within the range of the assassination shots, and that such a scope would allow even an untrained marksman to operate the weapon like a sharpshooter. And it was further determined that the rifle had little kickback, which would aid in maintaining aim after firing and rapidly working the bolt-action to reload. The false claims about Oswald’s rifle seem to have no end. It’s been claimed that it had a “hair trigger” that would have made sharpshooting difficult, but it was determined that its trigger needed 3 pounds of pressure, a full 2 pounds more than anything considered a hair trigger. Some have even claimed that Oswald could not have used it properly because it was set up for a left-handed person, but the $7 scope on Oswald’s rifle would be used exactly the same way by a lefty or a right-handed person. That only leaves the claim that Oswald could not work its bolt-action quickly enough to fire off the shots.

Three shells were found in the sniper’s nest on the sixth floor of the book Depository. According to the Warren Commission, the three shots had been fired in just about 5 to 5 and a half seconds, and during the FBI’s testing of the weapon, they determined that it took 2 and a quarter seconds to work the bolt action and take aim, which meant firing all three shots seemed impossible. However, it has been proven more than once that it is possible. A 1975 CBS documentary recorded the efforts of 11 marksmen to fire three bullets from a similar weapon at a moving target, and some were able to fire all three shots in only 4.1 seconds and still hit their marks. The House Select Committee a couple years later also conducted such tests, and as a result, they lowered the minimum time to fire three good shots from the Mannlicher-Carcano to less than 3 and a half seconds. And it must be kept in mind that, according to Marina, Oswald obsessively practiced the bolt-action on his rifle, such that he must have been expert at working it. Regardless, though, there is good reason to believe that Oswald took well more than 5 seconds to fire his three shots. You see, the entire basis of the 5 second time-frame is based on the Zapruder film, the 8mm home movie filmed by a local dressmaker. The Warren Commission worked under the assumption that the first shot fired must have hit, since Oswald must have had the time to aim carefully with that shot. In the film, Kennedy and the Governor seem fine, then Zapruder’s view of them is obscured by a sign, and afterward, they appear to be reacting to their gunshot wounds. Knowing that Kennedy must have first been struck while he was passing the sign, and further knowing that for a few moments as he approached the sign, until a certain point while passing behind the sign, he must have been obscured from the sniper’s view by a certain oak tree, it was determined that the first shot must have been fired just after emerging from the foliage and while obscured momentarily from Zapruder’s camera—at frame 210 of the Zapruder film. Knowing from the consensus of eyewitness testimony that the head shot, which can clearly be seen on the film, was the final shot, this allowed them to determine that the three shots had been fired in 5 to 5 and a half seconds. One of these bullets struck Kennedy in the back, exiting his neck and further injuring Governor Connally. The bullet believed to have caused these injuries was later discovered intact in Connally’s hospital gurney. The final bullet entered the back of Kennedy’s skull and created a massive exit wound on the right side of his head. The problem with the Warren Commission’s timeline is that they presumed the first bullet hit Kennedy in the back, the second bullet missed, and the third hit his head. However, there is strong evidence to suggest that Oswald’s first shot, the shot many witnesses believed was a backfire, was taken before Kennedy passed behind the oak tree’s foliage, and that this was the shot that missed, making the second and third, taken after he emerged, the only two that hit. This would make sense; one can imagine Oswald aiming and then taking a hurried shot before Kennedy went out of sight behind the foliage. Governor Connally, who survived, always insisted that the first shot, which he had heard, had not been the one that struck him. Multiple witnesses describe hearing the first shot just as their car turned from Houston onto Elm in front of the Depository and passed behind the oak tree there. Oswald’s acquaintance Buell Frazier, on the Depository steps, heard it that way, as did a witness half a block away, and another standing on the corner of Houston and Elm as Kennedy’s limo made its turn. Up on the railroad overpass, another witness described the first shot coming as the corner was taken, and even the President’s own driver and another Secret Service agent remembered it that way. In fact, some witnesses even report having seen sparks as a missed shot struck the pavement. One man even had minor injuries likely from chips of concrete striking his face. Nobel Prize-winning physicist Luis Alvarez (about whom I had occasion to speak when talking about his hypothesis regarding the mass extinction of dinosaurs in my episode on the Chicxulub Crater) suggested that evidence of a first missed shot could be discerned through “jiggle analysis” of the Zapruder film, that is, examining the film for blurs caused by Zapruder jerking when the first shot startled him. Sure enough, a significant jiggle was detected at the moment when Oswald would have been about to lose his shot because of the obscuring foliage as the President’s limo completed its turn. If, as this evidence suggests, this was the first of the three shots, then Oswald would have had something more like 8 whole seconds to fire the three rounds.

Oswald’s Mannlicher-Carcano rifle, Warren Commission exhibit 139.

Then there are those conspiracists who claim there were more than three shots. For writers who push the idea that shooters other than Oswald were present on Dealey Plaza, such as on the grassy knoll, it is imperative to suggest more than three shots were heard, or that they were heard from directions other than the book Depository. The 200 or so witness statements that speculate on the origin of shots are sometimes given as a percentage, to the effect that some startlingly high percentage of the witnesses believed the shots came from the grassy knoll rather than the book Depository, but conspiracist authors, such as Josiah Thompson in Six Seconds in Dallas, have been caught falsifying the numbers and misrepresenting the testimony. The fact is that 88 percent of the witnesses heard exactly three shots, and only 5 percent claimed they heard more. Likewise, the largest portion of the witnesses, 44 percent, could not determine where the shots came from, and of those who believed they could, most—28 percent—identified the Book Depository, with only 12 percent suggesting the grassy knoll, and only a measly 2 percent saying they heard gunshots from multiple directions. This last bit is important. Hardly anyone claimed they heard shots from more than one direction. So that means those who heard shots originating from a different direction than the Book Depository, from which we know three shots had been fired, were likely just confused by the acoustics of the plaza, which are known to make pinpointing the location of a sound difficult. Numerous witnesses even specifically mentioned being confused by echo patterns and admitting to uncertainty because of them. These acoustics could easily explain the few witness statements about a fourth or fifth shot as well. But the most confusion regarding number of shots was created by the House Select Committee in 1979, when they obsessed over a recording from Dallas police channels apparently captured from a motorcycle officer’s radio whose microphone was stuck on and capturing constant audio. The thing is, they didn’t know whose mic it was, or if it was even at Dealey Plaza that day. No gunshots were heard on the staticky recording, but they had experts pick it apart for inaudible sounds. A first set of experts said they found “impulses” that may have been gunshots, and after attempting to recreate the impulses by firing two rifles on Dealey Plaza, from the Depository and the grassy knoll, recording it, and then comparing these impulses, they suggested that the recording had been on or near Dealey and recorded four shots. Their certainty was 50 percent, but then just as the Committee had been ready to deliver its conclusions, a second pair of experts they consulted claimed it was as high as 95 percent. Then a Dallas policeman who had been accompanying the motorcade offered the dubious statement that sometimes his mic gets stuck, and that clinched it for them. The House Select Committee on Assassinations, which had been moving inexorably toward a finding that Oswald acted alone, changed their conclusion to declare that JFK was “probably assassinated as a result of a conspiracy,” all based on that mysterious recording. Conspiracy lovers just about did backflips, of course, but they were less excited when the officer afterward listened to the recording and said it couldn’t be his mic, because no sirens were heard when he accompanied the motorcade to Parkland Hospital. And the entire farce of the police channel recording would be revealed within a few years, when National Academy of Sciences experts made out some cross-talk on the police channel recording that was known to have been spoken by a sheriff one minute after the assassination. So the audio evidence of four shots that swayed the committee in favor of conspiracy, on which no gunshots or sirens could actually be heard, and which might not have even been a recording of audio at Dealey Plaza, had actually been recorded after the time in question, making the supposed “impulse patterns” observed by audio experts nothing but further crackling among the static.

Some eyewitnesses claimed they saw multiple shooters in the Depository that day, but their testimony has been discredited. For example, a prisoner in the Dallas County Jail claimed he was able to see two men in the sniper’s nest, but he was considered unreliable, not only because of his multiple arrests for behavior displaying mental instability, but also because the FBI determined one could not actually see the Depository from his cell. Other witnesses claimed to see multiple gunmen in windows other than the one around which the sniper’s nest had been made, or on different floors, but their testimony is invariably inconsistent, not matching established facts or even statements they made themselves in the immediate aftermath, and more than once was contradicted by people they had been with, who didn’t see the same thing and also indicated that the witnesses never mentioned seeing such things at the time. On the other hand, a great deal of consistent eyewitness testimony describes a lone man, fitting Oswald’s description, in the 6th floor window that had been turned into a sniper’s nest, even seeing the stacks of boxes behind him, and seeing the rifle in his hands. A Dallas Times Herald photographer and another cameraman who were both in the same motorcade vehicle witnessed this. A court clerk across the street pinpointed the window as well, said as much to his friend, and then directed a deputy sheriff to search there. A student on the street below looked up after the first shot and saw the barrel extended from that window, and then he saw the muzzle flare when it fired again. A fifteen year old boy who had been lifted onto a high perch across the street for a better view said he saw everything in the sniper’s nest, indicating just one shooter and running to a police officer immediately to report what he’d seen. A construction worker named Howard Brennan who had a perfect view of the sniper’s nest described a man fitting Oswald’s description to a T, and even described his lack of expression before the shooting and his self-satisfied smirk after.

Conspiracist writers relentlessly attempt to discredit Brennan because he didn’t express absolute certainty while later picking Oswald out of a lineup, but he did pick him, and later he explained his hesitance to express certainty as a product of fear, since he was having second thoughts about becoming a principal witness against the President’s assassin, thinking it could put a target on him if there really were some conspiracy, as some were already saying. Conspiracist authors like Jim Marrs, and Mark Lane, one of the earliest and most vociferous conspiracy peddlers, bring up Brennan’s poor eyesight to discredit him, saying he was nearsighted and thus could not have seen all the details he claimed. In fact, though, Brennan was farsighted. After the assassination, his eyesight was damaged in a sandblasting injury, but at the time of the assassination, he was actually peculiarly suited to discern the specific details he described from a distance. Regardless of all this testimony from outside the Depository, though, the statements of other Book Depository employees clear everything up. His fellow workers saw him on the sixth floor, lurking near the windows that looked out on the plaza. At about 11:45am, everyone took their lunch, intending to go down and watch the passing motorcade, and several remembered Oswald staying behind. One coworker even came back to get some cigarettes he had left on that floor, saw Oswald near the sniper’s nest window, and asked him if he was coming down for lunch. Oswald said he was not. Another employee came to the sixth floor to see where others were gathering and found it empty, but he did notice the high stacks of books in front of the south-east corner window. He ate his lunch quickly at a different window and then left to find others who were watching the motorcade, joining two friends at a fifth-floor window just below the sniper’s nest. All three, Harold Norman, Junior Jarman, and Bonnie Ray Williams, are critical witnesses, for they heard exactly three rifle shots coming from directly overhead, and they were even seen by some witnesses on the street leaning out their window and straining to see the window above them.

Commission Exhibits 1301-2, revealing Oswald’s sniper’s nest, courtesy the National Archives.

Much has been made of the supposed goings on at the grassy knoll further down the motorcade route from the Depository, but if we look closely at the reasons for suspecting a shooter was there, it starts to look entirely like a red herring. Remember that all the physical evidence and the preponderance of witness testimony indicate just three shots were fired, and all from the Depository. We’ve also established that echo patterns in Dealey Plaza confused the origin of sounds. Therefore, it is unsurprising that a couple police officers—not fifty, as some unreliable witness testimony claimed—went first to the grassy knoll to search for a gunman, and that they very quickly discerned there was nothing there. Being urged by most witnesses to search the Depository, that building quickly became the focus of their search. As with much conspiracy speculation, claims involving the grassy knoll often rely on mistaken witness statements, like that of a woman, Julia Ann Mercer, who was stuck in her car during the motorcade’s passage and said she saw men taking a gun case from a pickup truck and taking it to the grassy knoll. It turned out that the truck was stalled, and the men were getting tools from the back in order to fix it. The Dallas police had been monitoring the vehicle as they tried to maintain security on the plaza. Much of the speculation about the grassy knoll derives from witness statements that a puff of smoke was seen there during the shooting, but any modern ammunition a second shooter would have been using would be mostly smokeless, and the strong northerly wind that day would not have allowed smoke from a firearm to simply linger in the air. If something smoke-like were momentarily seen above the grassy knoll, it’s more likely that it came from the exhaust of an abandoned police motorcycle, as one witness described, or from the nearby steam pipe which would shortly thereafter scald the hands of a Dallas police officer searching the area. Other than these mistaken reports, there are the unreliable accounts of people seeking attention, like Jean Hill, who was swept into the drama because she took a Polaroid picture of the back of Kennedy’s limo at about the time of the third shot. Her early reports show a lack of reliability, getting all kinds of things wrong, like not being clear on the number of people in the car with the President, saying she saw a dog in the car, and claiming things happened that did not, for example, attributing exclamations to the First Lady that no one in the vehicle heard her make. Hill’s story became more and more lurid as she had further chances to tell it. First she added that she heard five or six shots, the later ones from an automatic weapon. Then she said police fired back on the shooters, which clearly never happened. Then she said she gave chase to a suspicious man, even though photos taken in the wake of the assassination picture her not having moved from her original spot on the south side of Elm. Her statement was afterward taken by a Times Herald reporter, but in later retellings, she claimed it was some mystery men impersonating Secret Service agents who questioned her. In that initial interview, she emphatically asserted that nothing had drawn her attention during the shooting, but more than 20 years later, she was enthusiastically providing conspiracist author Jim Marrs with details about gunmen firing from behind the fence on the grassy knoll. To explain why her later claims don’t line up with testimony she gave to the Warren Commission, she claims that she was coerced to alter her story, even though a stenographer was present and recorded none of the threats and manipulation she describes.

On and on it goes with the witness claims about the grassy knoll. A tiny portion of another woman’s faded Polaroid is blown up and said to show a mysterious badged man with a rifle, though in fact it just appears to be foliage. A man in a nearby railroad signal tower, who had a view behind the fence on the grassy knoll, said he saw two men behind the fence, standing apart as if they did not know each other, but then after speaking with conspiracist author Mark Lane, as happened with more than one witness, he changed his story to say he saw a flash of light as though one of the men had fired a gun. In fact, though, he has admitted that he was busy at the time of the assassination, having to work the control panel in his tower, which required him to have his back turned to the entire scene. Fifteen years after the fact, yet more grassy knoll shooter witnesses came forward, one claiming to have seen men with CIA IDs there, and asserting that he heard bullets flying past his ear. Another says he saw a man in a suit enter the railyard behind the grassy knoll and pass a rifle to another man, who disassembled it. But the problem with these latecomers’ claims is that others who were present in those areas did not see them there, casting doubt on whether they were there at all, or at least on whether they were where they claim to have been. This is the same credibility problem that all the grassy knoll claims suffer: there are other witnesses who were present and saw nothing of the sort. There are numerous witnesses confirmed to have been within view of the grassy knoll who saw no shooters peeking over the fence, and three who were standing just in front of the fence who certainly would have been aware if a rifle had been fired just behind their heads. And there were police stationed on the railroad overpass for security purposes who would have been able to spot any gunmen firing from that fence in broad daylight. Yet claims about the grassy knoll never cease. One writer, David Lifton, determined to make the grassy knoll idea work despite its problems, fell so deep into his scrutiny of faded photos that he began to see all sorts of strange things, convincing himself that conspirators had somehow managed to build fake trees on the knoll as a kind of hunting blind. He claims they must have built this artificial foliage without anyone on the busy plaza having noticed, and then afterward removed it in the days following the assassination, when the entire plaza was an active crime scene, again without anyone seeing them. And more than that, in the shapes and shadows of photo enhancements he made himself, he believed he could make out men in those fake trees wearing headsets and spiked imperial Prussian helmets, using periscopes and manning machine gun emplacements. In fact, he was pretty sure that he recognized General Douglas MacArthur somewhere among those black-and-white blotches. To illustrate the absurdity of the notion that General MacArthur was hiding in fake trees on the grassy knoll to oversee Kennedy’s assassination that day, it’s helpful to know that there was much mutual respect and admiration between the two, who had both served in the Pacific Theatre during World War II. At the time, MacArthur was 82 and frail, ailing from cirrhosis, which would take his life in less than a year. Kennedy had actually already made plans for MacArthur’s state funeral. Upon hearing the news about the assassination later that day, MacArthur sent Jackie Kennedy a powerful telegram, which reads, “I realize the utter futility of words at such a time, but the world of civilization shares the poignancy of this monumental tragedy. As a former comrade in arms, his death kills something within me.” Unfortunately, it’s quite typical of conspiracy speculators to not consider the human side of their claims, to toss out connections and spew ill-considered allegations, just hoping something sticks, never really considering that the names they throw out belong to actual people with rich lives and relationships and feelings.

A Polaroid photo taken the moment after the fatal head shot, in which can be seen a few people standing on the grassy knoll and, if we may judge by their postures and the direction of their gazes, clearly not hearing shots being fired from behind them.

The last and, to some, most important element to consider in this forensic mess, so relentlessly obfuscated by conspiracy speculation over the years, is that of the single bullet, dubbed the “magic bullet” by doubters, that was determined to have entered Kennedy’s back, exited his neck, and then caused multiple wounds in Governor Connally, thereafter remaining intact and ending up in the governor’s hospital gurney. There is, of course, much to be said about the actions and statements of the doctors who treated Kennedy at Parkland, the taking of his body out of Dallas on Air Force One, and the results of his autopsy at Bethesda, and the conspiracy narratives that have been spun around these events. In fact, there is so much that I will be releasing a patron exclusive on the topic. To conclude this episode, let us only look at the so-called “magic bullet” trajectory. Using the visible reactions of Kennedy and Connally on the Zapruder film to determine when they were struck, the Warren Commission and the House Select Committee encountered a timing problem. It appeared to them, looking at Kennedy’s arm movement and a later change in Connally’s facial expression, when he opens his mouth widely—a moment in the Zapruder film that Connally himself identifies as when he was shot—that there was too long between their reactions. They both tried to explain this away by saying Connally simply had a delayed reaction, but Connally himself said he instantly felt the bullet’s impact. This discrepancy, which conspiracy speculators take as proof they had been struck by different bullets, has since been resolved by expert modern enhancements of the Zapruder film in the 1990s. It can now clearly be seen that between frames 224 and 227, Kennedy assumed “Thorburn’s Position,” a neurological reaction to spinal injury as the bullet passed near his sixth vertebra, and Connally, nearly simultaneously changes his posture. His lapel can even be seen to flip up in the same spot where there was later seen a bullet hole in his shirt. The moment he picked as when he was hit, when he opens his mouth widely, was more likely a reaction to his first attempt to take a breath after being shot, when his lung collapsed. With the timing problem resolved, there is the further question of the bullet’s path through Connally’s chest and his right wrist and then into his thigh.

With the timing problem resolved, there is the further question of the bullet’s path through Connally’s chest and his right wrist and then into his thigh. The famous claim of those who mockingly call it a “magic bullet” is that it would have had to make impossible turns in midair to make all of Connally’s injuries. There is no surprising refutation here. That’s just simply untrue. Computer recreations of the Zapruder film have demonstrated that Connally was in a perfect position for the bullet to take its path, turned in his seat to search for the source of the first gunshot he had heard. Fired downward from the Depository’s sixth floor, as recreations proved it must have been, the bullet passed through Kennedy and entered Connally’s back, changed course slightly within his body when it struck his rib, exited below his right nipple, then passed through his wrist, which was in front of him holding his hat, and entered his thigh only a short way. The path of the bullet can even be discerned in the Zapruder film when one sees the movement of his hat at the moment his wrist is struck. Some have claimed the bullet later found in his gurney was too “pristine” and must have been planted, but it was a full metal jacket round, designed to pass through its targets as it did, and it was slightly damaged. The doctor treating Connally at Parkland immediately suspected the bullet must have survived intact when he saw how shallow the wound in his thigh was, and he even suggested Connally’s belongings be searched to find it. Lastly, anyone who watched the film JFK knows that much has been made of the motion of Kennedy’s head when he was struck by the last shot. “Back and to the left” echoes in our minds, having even become a darkly humorous meme, parodied in Seinfeld. Conspiracists claim the head’s backward movement demonstrates that he was not shot from behind but from in front, from the grassy knoll. However, again, conspiracy proponents are just talking out of their asses here, pretending to be experts on the human body’s reaction to gunshot wounds. Actually, doctors with expertise in gunshot wounds say that every person reacts differently depending on numerous factors. Some of the factors identified by experts for Kennedy’s backward movement include a neuromuscular spasm, triggered by the destruction of his cortex, causing his back and neck to stiffen, a reflex heightened by his tightly strapped on back brace, which prevented him from falling forward. Another factor is the so-called “jet effect” cited by Nobel prize-winner Luis Alvarez, who observed that the explosive force of his massive exit wound on the front right side of his head may have actually thrust him back in the opposite direction. Regardless, though, if conspiracists will only believe the shot came from behind if there is a forward motion, they should be satisfied by the fact that enhancements of the Zapruder film indeed show him jerking a couple inches forward before his motion back and to the left.

A diagram of the single bullet’s remarkably unmagical path, included in Posner’s Case Closed.

Further Reading

Bugliosi, Vincent. Reclaiming History : the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. First edition., W.W. Norton & Company, 2007.

McAdams, John. JFK Assassination Logic: How to Think about Claims of Conspiracy. Potomac Books, 2014.

Posner, Gerald. Case Closed: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK. Anchor Books, 1994.