The Demoniacs: The True Spirit of Possession and Exorcism

Maricica Irina Cornici and her brother Vasile grew up in an orphanage in Romania after their poverty-stricken father hanged himself. Once they became of age to leave the orphanage, they struggled to find work, relying on meager wages that Maricica managed to earn as a nanny to a series of families. It was a time when the Eastern Orthodox Church was growing in Romania, recruiting inexperienced young men and women to serve as priests and nuns in their monasteries after a long period of the church’s suppression. An old friend from their orphanage days informed them of just such an opportunity in the rural commune of Tanacu in Western Moldavia, so Maricica and Vasile, ready to give themselves over to the church, packed their few belongings and headed into the Romanian countryside, where they met a charismatic young priest with long red hair and beard named Corogeanu. This young priest fancied himself an exorcist and had become popular in the community as a healer, casting out evil from villagers who sought his help before seeking the advice of a physician for a variety of ailments that superstition told them might be the result of a diabolical influence rather than simply an illness or disease. Not long after her arrival at Tanacu, Maricica began to exhibit odd and even unacceptable behavior. It began with giggling during Mass, and eventually, it developed into Maricica mocking and cursing the clergy at the monastery. Her fellow nuns took to tying her up and leaving her in her room so that her behavior would not interrupt the services that villagers attended there, and eventually, the priest, Corogeanu, decided that she was possessed by a demon, or perhaps by the Devil himself. They took her from her room and chained her to a cross, stuffing a towel in her mouth to stifle her cursing and parading her about the church as Corogeanu performed his impromptu rite of exorcism. She endured this for three days, with no food or water beyond the dabbing of holy water on her lips. Unsurprisingly, she later died…after Corogeanu and the nuns gave her into the care of EMTs who took her in an ambulance to the nearest hospital. Yeah, that’s right. This did not take place in the Middle Ages. Rather shockingly, it occurred in 2005. Since these events, Corogeanu and the nuns were arrested and defrocked and the monastery at Tanacu shuttered. Blame has been cast not only on them, but also on the Eastern Orthodox Church for too quickly rushing to ordain uneducated priests in their rush to reestablish their influence following the fall of Communism in Romania. Corogeanu and others actually have had the nerve to blame the EMTs for administering too much adrenaline in their efforts to revive her in the ambulance, but the fact remains that the nuns had previously taken Maricica to the same hospital and had been informed that she displayed all the signs of being schizophrenic. Nevertheless, they rejected the opinion of modern medicine and chose to abuse her physically and psychologically by chaining her up, suffocating her, and starving her until she was unresponsive.

*

In starting this examination of cases of purported demonic possession and the practices of exorcism with a tale originating from the Eastern Orthodox Church, I may elicit objections that not only was Corogeanu practicing an illegitimate homebrewed rite of exorcism but also that the Eastern Orthodox Church generally does not have a strict and codified rite as does Roman Catholicism. People like to hold up Catholics as being a kind of gold standard when it comes to assessing demonic possession and eliminating scientific explanations and physical or psychological illness before resorting to exorcism. There’s currently a very enjoyable television drama that promotes this view called “Evil.” This notion is a result of the church’s own efforts to modernize the practice, as in 1999 Pope John Paul II updated the Church’s guidance on exorcisms to discourage the treatment of “victims of the imagination.” Rather than viewing this as a modernization of the barbaric rite, however, it should instead be considered the opposite. The Latin text in question simply affirmed the notion that some conditions cannot be treated medically or psychologically and encouraged the continued practice of exorcism. In fact, as of 2018, the Church appears to be mustering an army of new exorcists by educating a new generation of priests in the rite, in part as a bulwark, given claims from their priests in Mexico and other Latin American countries that demonic activity is on the rise. While the Catholic Church cautions against too lax a view on possession, they are still sending the message that more exorcists are needed to combat what they see as the growing diabolical influence in the world. However, not all those who answer this call to action are Catholic. There exists a subculture of Evangelical Protestants, Pentecostals and Charismatics, who believe themselves capable of casting out demons or “delivering” members of their congregation from the Devil’s power. Much of this is obvious theater during sermons in which preachers melodramatically touch the foreheads of their ecstatic followers, but behind closed doors, these would-be exorcists have no official strictures governing their historically harmful ceremonies.

Before I continue to historical cases of supposed possession and the exorcists that claimed to do battle with the demonic entities responsible, it should be said that the phenomenon is not unique to Christianity. German Psychologist Traugott Oesterreich, in his 1921 work Possession: Demoniacal and Other, Among Primitive Races, in Antiquity, the Middle Ages, and Modern Times, has provided the scholarly research showing the historical ubiquity of the notion, going back to Greek daimones, from which word we derive the word “demons.” The term meant something else entirely, signifying a kind of guardian or guiding deity, or even creative inner spirit, but as it was used to translate certain Hebrew terms for other kinds of spirits, it has become part of the Christian lexicon for evil spirits. Christian notions of demonology have passed to us from Assyrian and Persian religious notions, and the other modern monotheistic traditions, Judaism and Islam, all have their forms of demonic possession, whether by dybbuks or djinn, although a more detailed comparison would reveal these concepts to be very different from one another. However, monotheistic traditions do not hold a monopoly on the concept of spirit possession either. Austrian-American anthropologist Erika Bourguignon, in the 1960s through the 1980s, wrote a great deal about what she called “dissociational states” and the “possession trance,” with an emphasis on its cross-cultural nature. She surveyed 488 cultures and recognized some form of belief in spirit possession in 74% of them. Nevertheless, if we are to speak of demon possession in particular, and the practice of exorcising those demons, we are speaking principally of the monotheist traditions that dominate world religion, and among them, it is Christianity that was founded on exorcism. That may seem a strong claim, but it should be remembered that according to the gospels, Jesus Christ was an itinerant exorcist. The Gospel of John, which is so different in many ways from the others, makes no mention of Christ’s exorcisms, but it is a central aspect of Christ’s story as presented in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. And ironically, as we shall see, some of the most outrageous and telling cases of demonic possession in history supposedly affected women of the cloth, nuns who were said to have given themselves over symbolically in marriage to Christ, the first Christian exorcist.

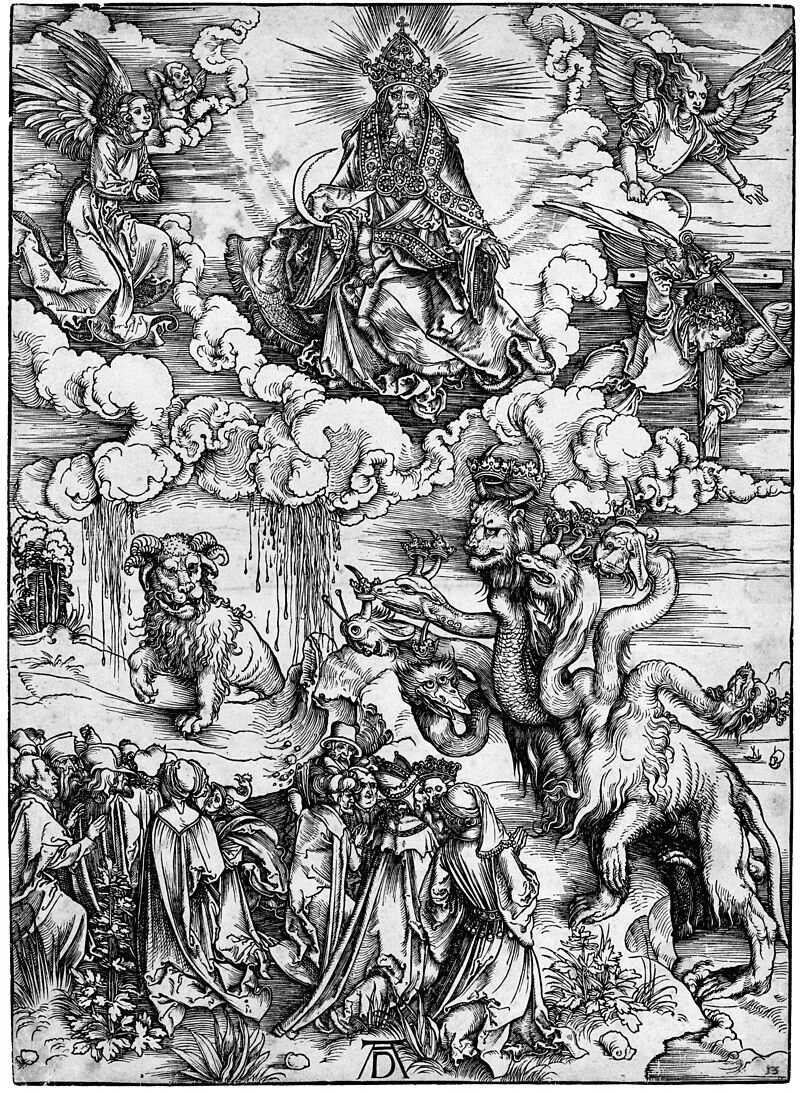

A depiction of Christ exorcising demons. Public domain.

One thing that the Catholic Church has thankfully done away with these days is witchcraft accusations and trials. The history of the Early Modern witch hunts is well known. I discussed it at length in a two-parter last Halloween. Perhaps because witchcraft accusations are today synonymous with ignorance and persecution, the Catholic Church wisely steers clear of such claims. Strange then that they are still willing to indulge, so to speak, in claims of demonic possession, which ever since a series of famous cases of mass possession at convents in 17th-century France have been closely related. It began in Marseille in 1609, when 14-year-old Madeleine de Mandols de la Palud, beginning her novitiate at the local Ursuline convent, told her superior that her confessor, Louis Gaufridy, who had spent a great deal of time with her at her father’s house over the last few years, had seduced her. It started when they had shared a peach one night, and it progressed eventually to fornication. After confiding this, she was transferred to an Ursuline convent at Aix-en-Provence, ostensibly because she had become ill, and it was there that she began to demonstrate symptoms associated with demonic possession. She suffered convulsions, she appeared to be repulsed by sacred objects, and she seemed to have knowledge that some believed could only have been acquired through clairvoyance. During the course of her possession and exorcism, she changed her story about Father Gaufridy, claiming that he had done more than seduce her. He had charmed her, she said, with that magic peach, had taken her to a witches’ sabbat and made her renounce God and sign a pact with the Devil in her own blood. It was because of Gaufridy that she had been possessed. As we have seen with other mass delusions, such as the Dancing Plague and the convulsionism during the following century in France, such experiences are contagious, either through the power of suggestion or due to a desire to receive attention and be a part of a consuming phenomenon. At Aix-en-Provence, numerous other nuns began to claim they too had been bewitched by Gaufridy and were also possessed. This resulted in a sensational mass exorcism, carried out before a huge captivated audience. The exorcist, Sébastien Michaëlis, a Dominican inquisitor who had made a name for himself as a witch hunter and demonologist, addressed the demons supposedly invading these nuns in Latin… but contrary to what was expected at the time, they did not reply in Latin. Michaëlis rationalized this by making up new rules, saying, with no apparent support for his claim, that the Devil did not typically speak in foreign languages when he inhabited the bodies of women. But of course, we can easily ascertain the truth that these women did not reply in Latin because they did not speak the language. Furthermore, it is clear that Madeleine de Mandols de la Palud could have conceived of her witchcraft claims against Gaufridy as a kind of revenge for his seduction, and that she cleverly avoided the stigma of witchcraft herself by claiming possession instead, for while witches were objects of scorn, demoniacs were objects of sympathy. The entire affair, strangely, may have simply been a way for her to rehabilitate her honor. In some ways it worked. After denying everything at first, Louis Gaufridy confessed to everything she alleged under torture and was burned alive. Madeleine de Mandols de la Palud became a penitent and for a time was viewed sympathetically, but eventually the stink of brimstone that clung to her proved too overpowering, and in 1653 she was tried as a witch herself.

The mass possessions at Aix-en-Provence were not just the first of their kind, but also they would serve as an example and precedent in the numerous copycat possessions to come. The next couple of times the Devil supposedly ran amok in a convent, it would start, rather creepily, more like a haunting. At the Bridgettine convent in Lille, in the Spanish Netherlands, nuns reported seeing specters and hearing strange noises before several of them began to display the symptoms of possession, receiving exorcisms throughout 1612, the year after the conclusion of the Aix-en-Provence affair. And 20 years later, in a single night in 1632, two nuns, including the prioress of the Ursuline convent in Loudun, Western France, claimed that they had been visited separately in their rooms by the ghost of their former confessor, who implored them for help. Two days later, one of the same nuns, along with a third, saw a black sphere which approached them and knocked them down. What followed were the classic signs of a haunting, or as some modern day exorcists might call it, a demonic infestation. Disembodied voices were heard and several nuns said they had been struck by some unseen force. Then the behavior of the nuns changed. They began to suffer uncontrolled fits of laughter and convulsions. The nuns claimed that a priest named Urbain Grandier, whom they had never actually met, was in fact a sorcerer and was the cause of their possession, much as Gaufridy had been blamed for the Aix-en-Provence possessions. Following the playbook of that earlier affair, the Catholic church turned the exorcism of the Loudun nuns into a spectacle, with thousands gathering to watch, and Urbain Grandier, much like Gaufridy before him, was convicted and burned at the stake. However, the Protestants of the region believed the entire affair to be a charade, claiming that the nuns’ confessor, Father Mignon, had coached them in their impostures with the approval of his Church superiors. Their reasons, it was claimed, were twofold. First, Urbain Grandier was a libertine and an embarrassment. He had had numerous affairs with local women and had even written a book against clerical celibacy. The other purpose the fraud served, besides ridding the church of Grandier, was to demonstrate the power of Catholic rites to defeat the Devil, an explanation that has been put forward for many witch purges and that explains the public exorcisms in France going all the way back to 1566, when a teen girl named Nicole Obry, who was said to be possessed by 30 demonic spirits, underwent exorcism rites in which the power of the Eucharist to harm an evil spirit was supposedly demonstrated on a public stage at a cathedral in Laon every day for two months, simply as a way to refute the Huguenots, who rejected the doctrine of the Real Presence of Chist’s body within the consecrated wafers. An alternative explanation, and something of a conspiracy theory, was that the powerful Cardinal Richelieu ordered the fraud as a pretext to rid himself of the troublesome priest Urbain Grandier, who had written a satire of him. No matter what the case, whether a mass delusion, religious propaganda, or a conspiracy against an unruly priest, or some combination of these, there are too many rational explanations to take the claims of the Loudun possessions seriously today.

A portrait of exorcist Sebastian Michaelis. Public domain.

About a decade after the events at Loudun, another nun’s claims about being seduced by a priest evolved into mass possession, public exorcism, and accusations of sorcery. Madeleine Bavent was the accuser, but in this case her allegations emerged years later in a written confession that sounds in many ways like the hoax claims of the Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk. She wrote that she had been seduced at 18 by a philandering Franciscan monk before entering the convent at Louviers, where the chaplain, she said, used to worship God in the nude and demanded his nuns did the same. This pervy chaplain was succeeded by Father Mathurin Picard, who Bavent said would turn Eucharist wafers into love charms and thereby receive sexual favors from his nuns. In this way, she wrote, Father Picard impregnated her. Picard and his assistant conducted black masses, at which the Devil visited them in the form of a black cat, she claimed. All of this in explanation of the convulsions and other possession symptoms that she and her fellow nuns were displaying. They had been bewitched from the grave by Father Picard, who had recently died. Her fellow nuns undergoing exorcism, however, had a different story. They said it was Madeleine Bavent who had caused them to be possessed. So while the Church dug up Father Picard and excommunicated his corpse just to be sure and ended up burning Picard’s assistant chaplain at the stake, Bavent too was tried as a witch. If she had concocted the story as revenge for a real sexual assault or in order to achieve some kind of agency in her patriarchal world, as has been argued before about such accusations, it certainly backfired on her. She was imprisoned in a subterranean dungeon, left to subsist for the next few years on bread and water three times a week, and died there within a few years. A couple years after the beginning of this affair, a treatise was written in Madeleine Bavent’s birthplace of Rouen, in which the specific indications of a genuine demonic possession are listed in an effort to better discern fakers from real demoniacs. The possessed must lead a wicked life (a strange requirement when the most famous purported demoniacs of the day were nuns), must think themselves possessed (which seems to ignore the possibility of delusions), must live outside the rules of society (a criteria that is likewise associated with many who were persecuted as witches), must blaspheme and be uncontrollable and violent (because surely no one could naturally do such things?), and must be tired of living (or in other words be suicidal, which again, is a criteria one need not be demonically possessed to meet). Among the few seemingly supernatural symptoms were signing of a pact with the devil, being troubled by spirits, showing a frightening countenance, making movements like an animal, and vomiting strange objects. This is at least an early indication that some thinkers at the time sought to differentiate “true” possessions from other, more naturally explained illnesses, but all such indications can be naturally explained as being lies, performances, and illusions, and these too go a long way toward explaining anything deemed to be a sign of a genuine possession even today.

The current signs of a genuine possession are all more focused on proving the supernatural: the ability to speak in a language the possessed person does not know, the demonstration of knowledge the possessed person could not know, and the display of supernatural strength. Just think on that a moment. There are exorcists going around believing they have proved the existence of supernatural phenomena. It makes you wonder why they haven’t brought in scholars and scientists to further publicize and study these definitively proven supernatural events. Of course, it’s because any of these might still have rational explanations. Supernatural strength may be subjective, based on what one imagines a particular person normally capable of, and the existence of augmented strength caused by adrenaline could scientifically explain such feats. As for displaying hidden knowledge or speaking a language one does not know, these could be easily faked with coaching or secret studies, especially today, with the Internet. Why would someone possibly want to fake possession, you may ask. Mental illness is an obvious answer, but the historical example of famous demoniac Marthe Brossier gives us alternative explanations. In 1598, Marthe Brossier attacked an older woman named Anne Chevreau in church and declared that the woman had bewitched her into being possessed. Anne Chevreau was arrested by civil rather than ecclesiastical authorities, and not being subjected to torture, she never confessed. This meant that Marthe Brossier had to prove herself possessed. Thus began her career as a demoniac, sent from one church to the next, having exorcism after exorcism, at which she satisfied many that she displayed the supernatural indications I’ve just mentioned. Her supernatural strength was observed in her strange bodily contortions and acrobatic movements like somersaults and backbends, which of course does not seem to have been an accurate test of strength at all but rather a test of how limber she was and perhaps of how committed she was to the performance. Furthermore, she seemed to prove her uncanny knowledge by telling audience members whether their loved ones were in heaven or their enemies bound for hell, which obviously couldn’t be proven accurate one way or another. As for speaking in a language unknown to her, she answered questions in Latin, but sometimes her answers seemed to betray a lack of understanding of the language, and when called on it, she typically dismissed the priests’ objections and threatened to stop talking altogether if they doubted her. What seems to have been happening was that her family was helping her in her charade. They had given her a book about the famous demoniac Nicole Obry, whom I previously mentioned, so that she might better learn how to behave like a woman possessed, and the local curé who had been her first exorcist, a family friend, was coaching her in Latin in order to fool ecclesiastic authorities. As it turns out, she was earning the family a tidy sum in profits from supporters who charitably donated to them.

The alleged diabolical pact of Urbain Grandier. Public domain.

While the making of money must have been a definite reason for the Brossier family’s complicity in her fraud, that was not Marthe’s reason for making the claims in the first place. Marthe had lost all hope for a respectable life. At the time, there were two paths for women of her class. She must either marry or become a nun. As she was one of four daughters and her father had lost his fortune and could therefore offer no dowry, marriage seemed impossible, and even entering a convent required some exchange of money, so neither had she been able to become a nun. She had been so upset by her position that she cut her hair and ran away from home pretending to be a man, which caused her and her family great shame when she was recognized and forced to return to her village of Romorantin. After that, as an unmarried, poor woman with a history of transgressive behavior, she may have actually feared being accused of witchcraft herself. In the last few years, numerous women in her position had been accused of witchcraft and of causing others to be possessed, leading to their execution. As mentioned before, while witches were reviled and murdered, their victims, the supposedly possessed, were typically objects of sympathy. Thus, Marthe Brossier, and maybe even her family, might have believed that claiming to be possessed was the only way to safeguard herself from witchcraft accusations, and it is perhaps no coincidence that she chose Anne Chevreau to accuse, since the Brossiers blamed certain other members of the Chevreau family for the failure of a marriage arrangement undertaken by one of Marthe’s sisters. Thus, with something of a family feud between them, revenge may also have been a motive. Whatever the case, Marthe must have rather enjoyed her role as a demoniac. She went from someone with no prospects and no power to being the principal bread winner of her family, the center of attention, an object of lust to many who watched her contort her body on public stages, and a woman empowered, because of the supposed demon inhabiting her, to speak her mind and even insult the men surrounding her. As her career as a demoniac continued, she found herself before crowds in Paris, having learned that she could further please her Catholic interrogators and exorcists if she had her demon tell the crowds that Protestants were followers of the Devil. But this was her undoing. Her anti-Huguenot propaganda may have put the Church on her side, but not the Crown. King Henri IV feared that she was upsetting the peace he had achieved between Catholics and Protestants with his recent Edict of Nantes, which pronounced tolerance for Huguenots. While the Church declared her possessed, medical doctors declared there was “nothing supernatural” about her condition, instead finding that she was faking it, and perhaps a bit mentally unwell, declaring there was “a large element of fraud, a small element of disease.” The king sided with the doctors and had her arrested on charges of fraud. In the end, the Paris court settled the matter by calling her an imposter and sending her back to her village, completely chastened and humiliated.

History is chock full of such cases of alleged possessions that either demonstrate the falseness of the phenomenon or can be debunked with just a little critical thought. In fact, I probably could have produced an entire series on this subject had I not feared that it would end up being a bit repetitive. Among the Puritans in Massachusetts Bay Colony, prior to the Salem Witch Trials, there was Elizabeth Knapp, a servant in the household of a preacher, whom the preacher claimed had become possessed, citing as evidence her convulsions and contortions, her claims to see beings who were not there, and her speaking in a strange voice without opening her mouth. Though a doctor could not explain it then, medicine today may identify epilepsy or Huntington’s chorea as a cause of her physical symptoms, both of which can lead to depression, mania, hallucination, and even schizophrenia, which may further explain her behavior. Living as she did with a fire and brimstone preacher who would later be involved in witchcraft trials, it is perhaps no surprise that she eventually confessed to having made a pact with the Devil, and there may have been some further motivation for actually feigning possession, using a kind of ventriloquism to affect a voice in the back of her throat, in that it allowed her to get out of work and verbally abuse her employer with impunity. The same medical conditions may explain many a case of supposed demonic possession, but sometimes, when an exorcism appears to cure said condition, as it did in the case of George Lukins, the Yatton Demoniac of 18th-century England, it would seem some further explanation may be needed. Lukins seemed compelled to scream, and bark, and sing backwards hymns in a voice that sounded inhuman to those who heard it. These violent fits began during a Christmas pageant, when he claims to have felt some phantom blow. He eventually told any who would listen that he was possessed by seven demons, and that they must be exorcised by seven clergymen. Perhaps Lukins was an impostor, faking possession for attention or in order to promote the wonderful works of God—for though his exorcists claimed they wanted to keep the ceremony secret, through some error, they said, many townsfolk discovered what they were doing, eavesdropping on the exorcism and, to their supposed chagrin, afterward publishing reports about the miracle they had performed. Or perhaps Lukins did genuinely suffer the fits described and only believed they were diabolical because of his religious worldview, a belief system so strong that he was cured simply by the placebo effect, demonstrating the power of suggestion, if indeed he was entirely healed at all and never again suffered any of his fits.

The exorcism of Madeleine Bavent. Public domain.

Very religious, also, was the 19th-century French demoniac Antoine Gay, a carpenter of Lyon who had once been accepted as a lay brother at an abbey but had to leave because of some nervous disorder that surely represented the early onset of whatever condition would later be mistaken for demonic possession. A priest who would later sign a certificate affirming the authenticity of Gay’s possession cited as “grounds” for his belief in Gay’s possession that he displayed a preternatural understanding of a language he did not know because he seemed to contort more violently when they spoke prayers over him in Latin, which of course proves nothing except that he could discern the appropriate time to writhe, and that he replied to questions posed in Latin, though he concedes that Gay only ever responded in French. As one who had previously sought to enter the mendicant life, it is possible he had studied the exorcism ritual enough to know the nature of the questions that would be posed to him, even if he could not speak Latin in any passable way. Later, when Gay was placed in an asylum for the mentally ill, another priest marveled at how Gay and a female patient who was also believed to be possessed would hold long arguments in an unknown language, which Antoine Gay later translated for the priest. It sounds like little more than a folie à deux, two mentally disturbed individuals feeding off each other’s delusions and shouting gibberish at each other. It’s absurd to think that the priest believed the mental patient’s subsequent explanation of the content of their exchange. Much as the seeming mastery of unknown languages convinced many of Antoine Gay’s possession, the mysterious indecipherable Devil’s Letter, purportedly written by a possessed Italian nun in 1676, captured a lot of imaginations recently when in 2017 researchers at the Ludum Science Center used a decryption algorithm to finally translate it. Legend had it that the possessed Sister Maria Crocifissa della Concezione woke up one morning covered in ink with a letter of jumbled characters from different archaic alphabets. The Ludum Center’s algorithm was able to decipher from it a message in Latin, Greek, Arabic and Runic letters that sounds like the Devil’s very voice, sowing doubt that God can save mortals. The problem is that, even after its algorithmic translation, the message doesn’t much sense, and some parts remain undeciphered, suggesting it may not have even been translated correctly. Additionally, it seems Sister Maria Crocifissa della Concezione may have been studying ancient languages during the more than 15 years she had been in the Benedictine convent, and that she may have suffered from bipolar disorder or perhaps even schizophrenia. Such a confluence of knowledge and interests and manic behavior or delusions could quite logically lead to her concocting a mishmash alphabet and writing out the words she believed the Devil was whispering to her.

In the modern era, possession and exorcisms have taken on an even darker quality, and I don’t mean a diabolical darkness. I refer to the consistent occurrence of mental illness being mischaracterized or misdiagnosed as demonic possession by clergyman and lay consultants, resulting in exorcism ceremonies that cause real psychological and physical harm, and even death, as in the Tanacu exorcism. Roland Doe, the 14-year-old boy whose widely embellished story inspired the book and film The Exorcist and whose psychiatrists all agreed he was a deeply disturbed child that should not have been exposed to such a ceremony, thankfully survived, but many another victim of this outmoded belief and practice have not been so lucky. Perhaps the most famous and egregious case of death by exorcism is that of Annaliese Michel, a young German epileptic who suffered from psychosis as a result of her seizures. Tragically, as she succumbed to mental illness and depression and a belief she was possessed, her family went along with her desire to stop seeing medical professionals and instead focus on exorcism, enabling Michel’s intention to die as a kind of atonement. Her family, her exorcist, and the Church that approved the ceremonies are complicit in Annaliese Michel’s suicide by exorcism. After 67 grueling exorcism sessions, she died of dehydration and malnutrition, her knees shattered from her ceaseless kneeling. The Church may like to hide behind the fact that subjects must request an exorcism these days, as though this represents a kind of release of liability, but the fact is that the mentally ill don’t always have the presence of mind or rational judgement to know what is in their best interests, and if they are rejecting modern medicine for faith healing like this, then neither do their families. I didn’t really believe that this episode would connect clearly to my last episode about religious arguments against vaccination, but as it turns out, they are closely connected. We see religious creeds and specifically Christian beliefs encouraging their faithful to reject science and modern medicine, and as a result, people are dying. Just to emphasize how evil and ongoing this threat is, as recently as January, 2020, news reports appeared revealing that exorcists are responsible for massacres. In an indigenous community in Panama, a religious group that called themselves the New Light of God kidnapped people from their homes, brandishing machetes and beating them. They held them captive, performing an exorcism ceremony that demanded they renounce their evil ways or be killed. Before authorities stopped them, they murdered seven innocents, including a pregnant woman and her five children. Doubtless these murderers rationalized their heinous acts in much the same way as did the Romanian priest Corogeanu, who rather than accept responsibility for the death of Maricica Irina Cornici, asserted that her death was God’s Will, saying horribly, "Only God knows why he took her … I think that's how God wanted her to be saved."

Further Reading

Bourguignon, Erika. “Introduction: A Framework for the Comparative Study of Altered States of Consciousness.” Religion, altered states of consciousness, and social change, The Ohio State University Press, 1973, pp. 3-35. The Ohio State University, kb.osu.edu/handle/1811/6294.

Kington, Tom. “Nun’s letters from Lucifer decoded via the dark web.” The Times, 7 Sep. 2017, www.thetimes.co.uk/article/nun-sister-maria-crocifissa-della-concezione-letters-from-lucifer-decoded-via-the-dar-web-d5jwx5mwk.

A narrative of the extraordinary case of George Lukins (of Yatton, Somersetshire) who was possessed of evil spirits, for near eighteen years: also an account of his remarkable deliverance, in the vestry-room of Temple Church, in the City of Bristol, extracted from the manuscripts of several persons who attended: to which is prefixed . a letter from the Rev. W. R. W. Thomas T. Stiles, 1805. U.S. National Library of Medicine, collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-0244605-bk.

Oesterreich, T.K. Possession: Demoniacal and Other among Primitive Races, in Antiquity, the Middle Ages, and Modern Times. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner And Company, 1930. Internet Archive, archive.org/stream/possessiondemoni031669mbp/possessiondemoni031669mbp_djvu.txt

Sluhovsky, Moshe. “The Devil in the Convent.” American Historical Review, vol. 107, no. 5, Dec. 2002, pp. 1379–1411. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1086/532851.

Smith, Craig S. “A Casualty on Romania's Road Back From Atheism.” The New York Times, 3 July 2005, www.nytimes.com/2005/07/03/world/europe/a-casualty-on-romanias-road-back-from-atheism.html.

Stephenson, Craig E. “The Possessions at Loudun: Tracking the Discourse of Dissociation.” Journal of Analytical Psychology, vol. 62, no. 4, Sept. 2017, pp. 544–566. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1111/1468-5922.12336.

Walker, Anita M., and Edmund H. Dickerman. “A Notorious Woman: Possession, Witchcraft and Sexuality in Seventeenth-Century Provence.” Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques, vol. 27, no. 1, Berghahn Books, 2001, pp. 1–26, www.jstor.org/stable/41299192.

---. “‘A Woman under the Influence’: A Case of Alleged Possession in Sixteenth-Century France.” The Sixteenth Century Journal, vol. 22, no. 3, The Sixteenth Century Journal, 1991, pp. 535–54, doi.org/10.2307/2541474.

Willard, Samuel. “A briefe account of a strange & unusuall Providence of God befallen to Elizabeth Knap of Groton.” Groton In The Witchcraft Times, edited by Samuel A. Green, 1883. Hanover College, history.hanover.edu/texts/Willard-Knap.html.