Unfit to Print; or A History of Bad News: the Party Press, Penny Papers, and Yellow Journalism

The epithet “fake news” is a curious thing. In its truest sense, it refers to media hoaxes, false stories formatted to look like they originated from legitimate news sources that are then widely spread online. These media hoaxes can best be compared to the hoaxes of 19th century- newspapers that I have previously spoken about in great detail. Many of these online news hoaxes, like the Great Moon Hoax and the Balloon Hoax and the New York Zoo Hoax, are perpetrated in order to earn the hoaxer money. In the 19th-century press, this was achieved through increased circulation, but online news hoaxes earn money through clicks and ad revenue. They are also comparable to the many fake news stories by Joseph Mulhatton which I have written about in that they may be small in scale and anonymous and could be perpetrated just for a laugh. But the online news hoaxes of today may also be used as disinformation and propaganda by a foreign power or political campaigns. Still, this too may not be so very different from newspaper practices in the past. The thing is that this term, “fake news,” has often been lobbed at reputable, legacy news organizations simply because their news coverage is inconvenient or unflattering. It is a mark of the post-truth era that politicians can have their corruption exposed by investigative journalists but can save face simply by calling the news reports “fake.” Meanwhile, some of the most outrageously false and dangerous news reporting doesn’t typically get called “fake news.” I am thinking here of the various platforms of Rupert Murdoch’s conservative media empire. Murdoch’s sensational publications in the UK are not called “fake news,” but rather tabloids, and here in America, they masquerade as a “fair and balanced” alternative to the “mainstream media” that they try to undermine by calling fake. Their stock in trade is projection and gaslighting. They are pissing on their viewer’s mouths and telling them it’s drinking water, while screaming that they cannot trust what comes out of their tap. As I write this, Fox News host Tucker Carlson has been actively discouraging COVID vaccination with blatantly false claims about widespread deaths being attributed to them. Fox News pundits Jeanine Pirro, Maria Bartiromo, and Lou Dobbs were instrumental in spreading baseless election fraud conspiracy claims that incited insurrection and murder on January 6th. And it’s not limited to the sensational cable news channel. During the election, the Murdoch-owned New York Post was instrumental in promoting the false October Surprise story about Hunter Biden’s laptop, citing only Steve Bannon and Rudy Giuliani as their sources. While conservative personalities decry “biased journalism” as “fake news,” they prop up the most biased and fake journalistic outlets active today. Ironically, though, all complaints about bias and fake news, whether in the mainstream media or in alternative media, seems implicitly nostalgic, looking back mournfully on some vague former time when the press is supposed to have been a paragon of fairness and objectivity. But did that lost golden age of journalistic integrity exist? And can the history of American journalism put the exploits of Murdoch’s News Corp in context?

In order to trace the evolution of the news industry, we must first understand its beginnings. The origins of newspapers can be found in England, in the 17th century, when wealthy country gentlemen who wished to stay informed as to the goings-on at the royal court were obliged to hire correspondents who would write them letters with the latest gossip. These were correspondents in the oldest sense of the term, in that they corresponded with their employers through the Royal Mail service, sending “news-letters.” Here in America, our first news service evolved from this tradition in the very early 18th century, with the Boston News-Letter. These gossip publications were typically published by a postmaster and consumed right there in the post office, the hub of each village’s communication with the world. By the time that newsletters began to be circulated here in the U.S., though, they began to evolve back in England. The news that people wanted was political, coming out of parliament, which convened secretly, so that only certain invited visitors could observe the proceedings in the “Stranger’s Gallery.” Some visitors saw an opportunity and would write reports from memory of what was said and done, or would even furtively try to take down notes while in attendance. Gradually, these political news-letters moved from simply reporting parliamentary gossip and began publishing opinions. Formerly, political opinions were printed and disseminated as broadsides and pamphlets, but that role was taken over by newspaper editors in the early 18th century, and from there, it did not take long for newspapers to become the mouth-pieces of certain political parties. This is the dawn of the “party press” age of journalism, both in England and America, when newspapers reported facts and opinions with a view toward benefiting the image of a certain political party and winning readers to that party’s side. And which party a newspaper supported was not dependent on the editor’s view. Rather, politicians and parties subsidized newspapers, making them official organs. One misconception about news publications today and a principal criticism of the “mainstream media,” is that it is a cardinal sin for a journalist to express an opinion or take a side, but opinion has been a major element journalism going all the way back to its beginnings. In later years, it’s true, ideas of journalistic integrity demanded that editorial opinion be clearly labeled and separated from “news,” but even so, some leaning toward and favoring of a certain viewpoint even in reportage has always been acceptable and even encouraged. It’s what is called “editorial direction,” and it is a major draw for a paper. If one doesn’t like a paper’s views, one can find another paper that better suits them. In fact, when we talk about “freedom of the press,” it is precisely the freedom to express opinions that is protected, not the freedom to report facts.

First issue of the Boston News-Letter, regarded as the first continuously published newspaper in British North America. Published April 24, 1704. Public Domain.

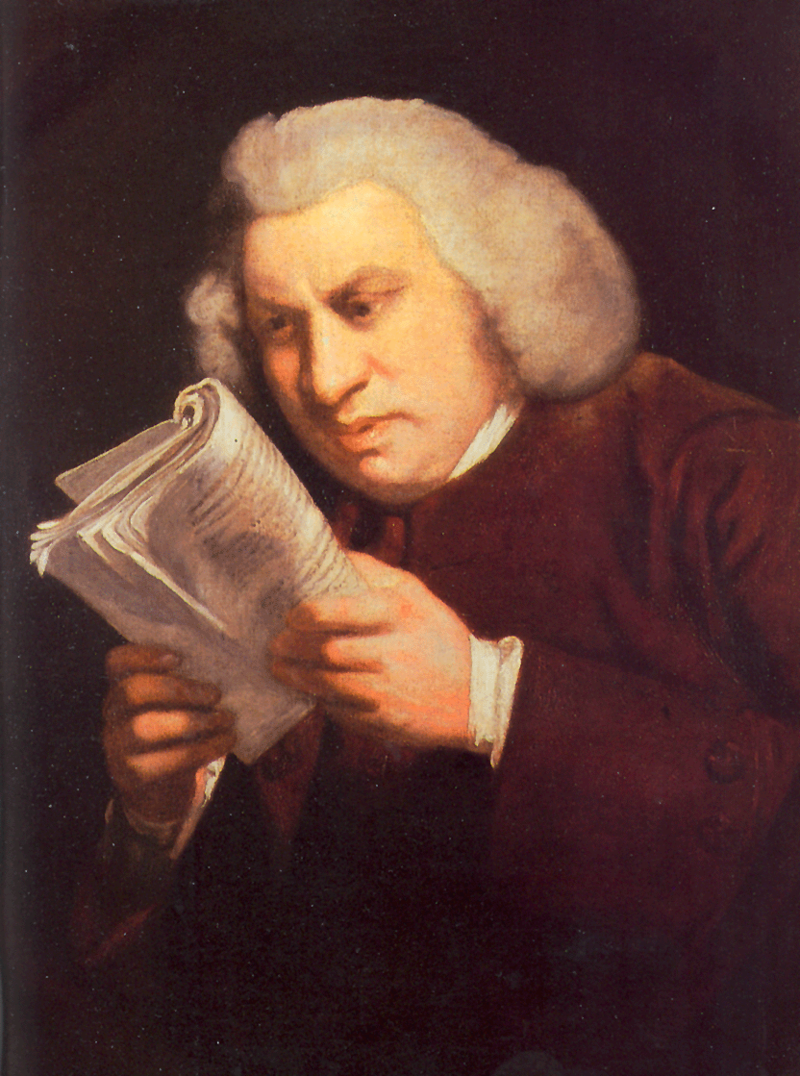

Perhaps Rupert Murdoch and his News Corp represent a return to the age of the party press. Interestingly, his newspaper, The New York Post, started out as an organ of the Federalist Party, founded in 1801 by Alexander Hamilton after the election of Thomas Jefferson, about which I spoke a great deal in more than one episode last autumn. Hamilton wanted a mouth-piece to compete with Thomas Jefferson’s National Intelligencer, which had begun publication the year before. And it should be said that the party press era was not entirely negative. Indeed, partisan journalism has been credited by James Baughman of the Center for Journalism Ethics with greatly increasing democratic participation and voter turnout, and with 2020’s spike in voter participation, we may be seeing the same effect today. But let me qualify. In the party press era, as today, newspapers colored the facts, gave one-sided versions of events, and ignored or chose not to emphasize stories that made political rivals look good. This is certainly something that we observe today, on both sides, even if more so on one side than the other. That kind of bias is one thing, but making up the news, misrepresenting or inventing events, or purposely misreporting in order to make one party look good or another party look bad is something else entirely. One egregious example of such manufacturing of the news during the party press era occurred when Samuel Johnson, reporting on parliamentary proceedings for Cave’s magazine, apparently made up an entire speech that he wasn’t present in the Stranger’s Gallery to hear, basing his remarks on a second-hand description of the speech. This is certainly deceptive, but the fact that Johnson was widely praised for his seeming neutrality, despite Johnson himself confessing that he always did what he could to make the Whigs look bad in his reporting, demonstrates that the kind of brazenly false news leveraged as propaganda that we see today may not have shown up until later. Here in America, in the 19th century, the party press gave us lurid personal scandals, like the competing newspaper coverage of Andrew Jackson’s marriage—some characterizing him as having seduced a wife away from her husband and marrying her before her divorce was final, and others depicting him as an innocent victim of character assassination, asserting her marriage had been abusive and that Jackson did not know the divorce was not yet final—but these are instances of gossip that are hard to characterize as purposeful disinformation. I struggle to find instances of outright deception in the party press era, so let us move on.

In 1833, a new age of journalism commenced with the so-called Penny Press era, when Benjamin Day founded the New York Sun. What made the Sun and other penny papers different was its price, first of all—one cent compared to the 6 cents that most other papers cost—but also its intended audience. Using the steam press, they were able to mass produce the paper cheaply, which meant, in order to make money, they needed the masses to take up reading the news, many of whom were not interested in the politics peddled by partisan papers. So they changed their approach, writing shorter, more easily digestible pieces using simpler language, and focusing on practical and relevant news over politics, as well as on more human stories. In this way, penny papers appealed to the common folk and immigrants, or as Day put it, “mechanics and the masses generally.” With this wider readership also came better advertising revenue, and thus the business model of newspapers would be changed forever, relying more on wide circulation than on political subsidization for profit. And of course, the Penny Press era gave us the first dramatic examples of really fake news, the Great Moon Hoax and the Balloon-Hoax, which I have previously discussed in some detail. It is tempting to suggest, then, that whenever there is a sea change in the accessibility of news and the medium by which it is delivered, fake news flourishes. It began with the Penny Press, and continued with the advent of radio broadcast and Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds, and then reached its height with the Internet, the ultimate democratization of information access.

Samuel Johnson, an early manufacturer of partisan news. Public Domain.

But that would be an oversimplification. First of all, as I recently discussed, the fake news related to the War of the Worlds broadcast was not on the radio but rather in the papers, which exaggerated the panic it had caused. And furthermore, the era of the penny press also led us to the highest ideals of journalistic integrity. This was the era in which the independent press emerged. Benjamin Day’s rival, James Gordon Bennett, expressed these ideals clearly when he founded his competing penny paper, the New York Herald: “We shall support no party—be the agent of no faction or coterie, and we care nothing for any election, or any candidate from president down to constable.” It was a declaration of the press as an autonomous and objective force that could act as a check on political power. The Herald itself may not have lived up to the ideals Bennett espoused. It would go on to engage in the very kind of hoaxing it criticized the Sun for perpetrating, like their New York Zoo hoax about escaped animals, and it would by no means remain carefully neutral in politics, in fact favoring the nativist, anti-Catholic Know-Nothing Party. And as a penny paper, their coverage tended to the sensational, especially in the scandalous Robinson-Jewett case, a notorious sex and murder scandal, during which Bennett was the first to issue extra editions. But Bennett pioneered journalistic practices like reportage based on the observations of correspondents and interviews. His paper was one of the first to uncover local corruption, as well, a practice of investigative journalism that would go on to inspire some of the greatest work of the independent press in the 19th century, when the New York Times’ coverage of Boss Tweed became instrumental in taking down the Tammany Hall political machine in the 1870s. The development of the penny press is therefore clearly related to the development of both news hoaxes and to our highest journalistic standards. Still, the kind of hoaxes and sensationalism that came out of the penny press was not the kind of disinformation and propaganda we see from partisan news outlets today. Perhaps, then, we can find a forerunner of this kind of fake news in the so-called “yellow press.”

In many ways, the era of Yellow Journalism also evolved from the practices of the Penny Press and independent journalism. What Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, the two eventual magnates of the yellow press, had learned from their predecessors was that news was best told as a “story.” They took to heart what James Gordon Bennett once asserted, that the purpose of news “is not to instruct but to startle and amuse.” For Pulitzer, in his St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and later in his New York paper, the World, this meant investigative watchdog journalism such as what the independent press had pioneered in the 19th century. Pulitzer likewise crusaded against corruption, but often as a way of courting poor immigrant readers, for example focusing on exposing conditions in the tenements where these prospective readers lived. Since his crusading was in some cases a matter of business, Pulitzer has been credited with inventing muckraking, the kind of journalism that seeks to cause outrage and scandal even when it may not be warranted. On the other hand, William Randolph Hearst, who got his start in San Francisco with his paper the Examiner, courted female readers with human interest stories and a certain brand of muckraking story that came to be known as a “sob story.” It began with rumors of a poorly managed hospital. The paper chose a female cub reporter to investigate, which she did by pretending to faint on the street in order to be admitted. This reporter, Winifred Black, wrote a story about women’s treatment in the hospital that was said to have made women sob with every line, earning her the nickname “sob sister,” and launching her career as a muckraker with a dedicated audience of women readers. Other newspapers even tried to recreate this success, building whole teams, or “sob squads,” to churn out similar stories. These two newspaper empires, that of Pulitzer and that of Hearst, with their comparable approaches to muckraking and sensational reporting may have come closest to the kind of political engineering that we see from Rupert Murdoch and News Corp today, for they are widely credited with having led the U.S. into war with Spain. But how accurate is that characterization?

Hearst’s self-congratulatory newspaper coverage of his own jailbreak exploit in Cuba. Public Domain.

Since the mid-19th century, there had been more than one armed rebellion in Cuba against their Spanish colonial rulers. In 1895, rumblings of revolution began again, organized by Cuban exiles in the U.S. and Latin America and commenced as a series of simultaneous uprisings against colonial authority. In the U.S., Pulitzer’s and Hearst’s newspapers favored the cause of the rebels and vilified the Spanish. Hearst especially seems to have put the entire weight of his editorial influence into convincing the American public that they should cheer on the rebels, and eventually, that the U.S. must itself become involved. Hearst’s motivations are a matter of some dispute. Humanitarian concern and democratic ideals may indeed have played a substantial role, making the yellow press’s focus on the rebellion less selfish and unsavory than it is typically portrayed. But it is clear that Hearst, even then, had political ambitions, and to be seen as bolstering the cause of democracy would certainly burnish his reputation. Then there is the distinct possibility that he believed war with Spain would be good for business. Indeed, it would turn out to be a massive boon to his newspapers’ circulation, so perhaps, as has been his usual characterization, Hearst did after all have his eye on the bottom line, though it was more likely a combination of these motivations. But Hearst’s desire for the U.S. to go to war with Spain and his willingness to foment it by manipulating public opinion has certainly been exaggerated, to the point that it has become a myth. The favorite anecdote of those who promote this view is that Hearst sent an illustrator to Cuba in January 1897, and when the illustrator wrote him saying, “There is no trouble here. There will be no war,” Hearst replied, “You furnish the pictures. I’ll furnish the war.” However, media historian W. Joseph Campbell has proven through meticulous research that this exchange never took place. First of all, there is no evidence for the existence of these telegrams, and the anecdote first appeared in a memoir by a correspondent of Hearst’s who was not involved at all and was actually in Europe at the time, who used the anecdote not to disparage the yellow press, but to praise their foresight. Second, in 1897, there was already war in Cuba, and that was Hearst’s whole reason for sending the illustrator there. Moreover, Hearst’s editorial position in January of 1897 was that the rebels would succeed in throwing off the colonial yoke; his campaign for U.S. military intervention would not begin for some time. While this exchange is certainly a myth, though, it should not be thought that Hearst did not overstep in his newspaper coverage of the situation in Cuba.

Since the “sob story” had served him so well, Hearst cast about searching for the story of a mistreated woman. Such a story would appeal emotionally to both female readers who imagined what they would do if they ever found themselves in such distress and to male readers who fancied themselves chivalrous. He found just the story he needed in Evangelina Cosío Y Cisneros. This 18-year-old woman had visited the Isle of Pines in Cuba with some companions in 1896, intending to visit with her father, a rebel who was confined to the island. According to later accounts, a Spanish colonel one night came to her room and made unwanted sexual advances on her, but her companions came to her aid upon hearing her cries. Pulling the rapist off of her, they tied him to a chair, but a patrol of other Spanish officers happened upon the scene and arrested them. Evangelina Cisneros was charged with luring the colonel into a trap and thrown into a jail for prostitutes. Hearst’s flagship paper, the New York Journal-American, turned Cisneros into a paragon of feminine purity who was being brutalized, kept among fallen women, and regularly subjected to abuse. She became in his newspaper columns a symbol of all the innocent Cuban women that the Spanish were ravishing and debasing, making of the rebels who fought to protect these damsels in distress heroes firmly planted on the moral high ground. In fact, there is evidence that Cisneros was more of a pants-wearing, cigar-chomping rebel herself, and that she may in fact have been enacting some rebel plan at the time of her arrest, but otherwise, much of Hearst’s portrayal of her situation seems accurate. This “Flower of Cuba,” as the Hearst papers called her, was to be shipped overseas to a Spanish penal colony in North Africa. But Hearst had other plans. In one of the most astonishing instances of manufacturing the news in American history, he sent a rough-and-tumble correspondent, Karl Decker, to Havana to break her out of jail, and they succeeded. Exactly how this daring escape was effected remains unclear—there are stories of a file being smuggled in to her, or drugged bonbons that she used to put her cellmates to sleep. Regardless of how it was accomplished, we know that she was successfully sprung from the jail, hidden, and then put secretly aboard a ship back to America, where Hearst had her paraded around the country to tell Americans about the cruelties of the Spanish in Cuba. Rather than causing a scandal over the legality of such an unsanctioned action overseas or the role of the press in making news, Hearst’s exploit was widely praised, of course in Hearst’s papers but in others as well. Pulitzer, though, was quick to suggest that the jailbreak was a hoax, insisting that the Spanish authorities must have allowed it to happen, and this has been an enduring characterization of the affair. However, W. Joseph Campbell has uncovered through an examination of contemporary diplomatic correspondence that certain U.S. diplomats were involved with the jailbreak, and that they faced considerable risks in being involved. Moreover, the Spanish authorities ordered a search for Cisneros after her disappearance, showing that they had not winked at her escape. So while some myths certainly surround the level of involvement of the yellow press in Cuba in 1897, this was not one of them. William Randolph Hearst did indeed orchestrate the liberation of a Cuban prisoner of war.

While the “Cisneros Affair” certainly galvanized the American public to espouse the cause of the Cuban rebels, it was another dramatic event that is usually identified as the tipping point for American military intervention in the Cuban War of Independence. This event is not disputed as a myth, but it has turned out to be an enduring mystery. In January of 1898, U.S. President William McKinley had the battleship USS Maine anchored in Havana Harbor as a demonstration of US power and determination to protect U.S. citizens in the war-torn country. On February 15th, while the crew slept in their quarters on the forward end of the vessel, an explosion occurred. There had been 354 men aboard the ship, and 266 of them perished in the explosion and the resulting fires as the ship sank into the harbor. Hearst’s Journal and Pulitzer’s World both put this tragedy on the front page every day afterward, of course, asserting that the explosion had been an attack, an act of war. Hearst even offered a $50,000 reward for evidence of who was responsible. The U.S. Navy wasted no time in launching an inquiry, which determined within a month that an underwater mine had detonated, in turn igniting the ship’s forward magazine. However, some of the experts consulted in the inquiry came to a different conclusion, suggesting instead that coal in the bunker adjacent to the magazine had spontaneously combusted. This scenario would have been more consistent with the findings of a Spanish inquiry, which argued that it is unusual for a ship’s munitions to explode when it is sunk by an underwater mine. Moreover, a spout of water would typically be seen when a mine detonates, and dead fish would afterward be found, neither of which was the case in Havana Harbor that evening. Numerous investigations have failed to resolve this mystery. Perhaps the Spanish inquiry’s conclusions are less than trustworthy because they surely were seeking to absolve themselves. And there is just as little evidence for an internal explosion as there is for an external one. In fact, the spontaneous combustion of coal appears to be just as uncommon as a ship’s magazine detonating after being struck by a mine. But none of this mattered to the yellow press, which ignored the Spanish inquiry and the dissenting expert opinions and declared to the world that the Spanish had murdered U.S. navy men in a brazen act of war. In less than a month, Congress declared war, and many an American sailor was heard to repeat the headlines of the yellow press in their war cries: “Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!”

Hearst’s inflammatory newspaper coverage of the USS Maine explosion. Public Domain.

In considering the yellow press as a possible precursor of today’s disinformation outlets, we must reconsider what we presume to be true about yellow journalism. Historians have shown the “I’ll furnish the war” quote to have been a myth, so the truth about the complex myriad of factors that led to U.S. involvement in the Cuban War of Independence has likely been obscured by this appealing fiction. It is not as though the American public would not have learned of the events without the yellow press or would not otherwise have come to favor U.S. involvement. There were other, more respectable newspapers also reporting on the Cuban rebellion then, just as today there are many more scrupulous news outlets that consumers of Rupert Murdoch’s brand of news could seek out instead. And yellow journalism and public opinion alone did not sway President McKinley to pursue war. There had been jingoists in Congress pushing the same war agenda every step of the way. In the same way, today, Fox News and conservative media generally may not be inventing the talking points and leading this disinformation war so much as following the lead of the GOP, recognizing their niche market and continually pursuing their audience down whatever fringe path they’ve been led. Notwithstanding these parallels, though, I still find no examples from the history of American journalism that match the brazen manipulation, the invention of false narratives, the shameless promotion of disinformation regardless of potential public harms that we see in the media produced by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp, especially Fox News Channel. They seem to represent the worst of every era, seemingly beholden to a political party as in the party press era, trading in oversimplified sensationalism in order to appeal to the everyman as in the penny paper era, and willing to manufacture news as in the age of yellow journalism. But Hearst and his empire were not really anything like Murdoch and News Corp. First of all, Hearst was driven by political ambitions, trying to parlay his newspaper platform into a Democratic presidential nomination. Murdoch appears to be motivated by the pursuit of wealth and a sinister ideology. Hearst envisioned a kind of “journalism of action” that would engage in democratic and humanitarian activism, certainly for the purposes of self-promotion but never seeking to do harm. But just this year, Fox News has been promoting conspiracy theories that encouraged the overturning of a free and fair election and engaging in anti-vaxxer science denial that will result in lost lives; they are attacking democracy and public health. To me, this seems like a new and unprecedented form of flawed journalism. We find ourselves in the era of the propaganda press. And what’s truly scary is that Fox News and the other outlets within Murdoch’s News Corp are no longer even the worst offenders, having shown clear signs of tempering their rhetoric in at least some of their programs—typically the ones that they would have a hard time claiming are for entertainment purposes only. Disinformation purveyors have grown in the last couple decades, with NewsMax, Breitbart, and One America News Network becoming the worst offenders. But credible news reporting and reliable outlets remain, the most impartial and conscientious being Associated Press and Reuters reportage. As for major legacy newspapers and other big cable news channels, yes, bias and the favoring of viewpoints is present, as it always has been. American consumers of news need to stop expecting anything different, learn to read laterally across platforms for a wider variety of editorial slants, and concentrate, most importantly, on rooting out barefaced propaganda.

Further Reading

Borch, Fred L., and Robert F. Dorr. "Maine's sinking still a mystery, 110 years later." Navy Times, sec. Transitions, 21 Jan. 2008, p. 36. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current, infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=news/11E7C6BBE345B960.

Campbell, W. Joseph. “‘I’ll Furnish the War: The Making of a Media Myth.” Getting It Wrong: Ten of the Greatest Misreported Stories in American Journalism, University of California Press, 2010, pp. 9-25.

———. “Not a Hoax: New Evidence in the New York Journal’s Rescue of Evangelina Cisneros.” American Journalism, vol. 19, no. 4, 2002, pp. 67-94. W. Joseph Campbell, PhD, fs2.american.edu/wjc/www/nothoax.htm.

———. “Not Likely Sent: the Remington-Hearst ‘Telegrams.’” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, vol. 77, no. 2, 2000, pp. 405-422. W. Joseph Campbell, PhD, fs2.american.edu/wjc/www/documents/Article_NotLikelySent.pdf.

———. “William Randolph Hearst: Mythical Media Bogeyman.” BBC News, 14 Aug. 2011, www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-14512411

Lowry, Elizabeth. “The Flower of Cuba: Rhetoric, Representation, and Circulation at the Outbreak of the Spanish-American War.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 32, no. 2, 2013, pp. 174–190. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42003444.

Park, Robert E. “The Natural History of the Newspaper.” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 29, no. 3, 1923, pp. 273–289. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2764232.

Pérez, Louis A. “The Meaning of the Maine: Causation and the Historiography of the Spanish-American War.” Pacific Historical Review, vol. 58, no. 3, 1989, pp. 293–322. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3640268.

Taylor, WIlliam. “USS Maine Explosion.” Disasters and Tragic Events: An Encyclopedia of Catastrophes in American History [2 Volumes], vol. 1, 2014, pp. 164-166. ABC-CLIO, 2014. EBSCOhost, search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.deltacollege.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=781660&site=ehost-live&scope=site.