The Feat of the Flying Friar: St. Joseph of Cupertino

Today, when one thinks of a human being having the ability of unencumbered flight, being able to fly without the aid of a machine, one almost certainly thinks of it in the context of superhuman powers like those observed in the superhero characters that have dominated blockbuster cinema for the last decade. This is the easiest context into which one can place such notions, as the idea of a man flying has been associated with comic book characters since 1939, when Namor the Submariner first took flight. While Superman first appeared in 1938, it is a little known fact that he wasn’t actually depicted in flight until 1941. It is interesting to note, however, that neither of these iconic first flyers were exactly human: Namor was a mutant half-Atlantean, and Superman, of course, was a Kryptonian extraterrestrial. Soon, flying human superheroes became relatively common, but they seem always to come by their abilities of flight through some technology or magic or because of some chemical or radioactive accident or science-fictional mutation. To find stories of regular human beings who supposedly really could fly, we must look further back, to a time when superhuman abilities were thought to have been conferred on people by some deity. And even then, these powers of flight were possessed by people either considered heroes or villains, for it was thought they had been granted the gift of flight either by a benevolent god or a malevolent devil. The heretic Simon Magus, whose name indicates a Zoroastrian faith but whose legend claims he was the origin of Gnosticism and other heresies, is said in an apocryphal work, the Acts of Peter, to have “amazed the multitudes by flying.” Peter prayed to his god, beseeching him to make Simon Magus fall, which he did, breaking his leg in three places, whereupon the crowd turned on him and cast stones at him. But flight was not only seen as a matter of trickery or a feat performed by heretics who claimed to be god; it was also a feat performed by the most devout and faithful, such as St. Dunstan, St. Dominic, St. Francis of Assisi, Thomas Aquinas, St. Edmund, archbishop of Canterbury, Blessed James of Illyria, Savonarola, St. Ignatius Loyola, St. Philip Neri, and St. Peter of Alcantara, and it was seen to be a sign of saintliness comparable to the stigmata, or the spontaneous appearance of Christ’s wounds, another sign of divine favor said to have been bestowed on St. Francis of Assisi. Another saint, Giuseppe of Copertino, is said to have flown thousands of times and to have been witnessed in flight by thousands who would testify to the authenticity of his flights. What, then, is a modern, rational mind to make of such claims?

According to the apocryphal Acts of Peter, when Saint Peter saw Simon Magus flying in the Roman Forum, he prayed to his god to make him fall and thereby disprove his claims of divinity. However, interestingly, the text calls this an illusion that carried away or amazed those who witnessed it. Likewise, earlier miracles performed by Simon Magus are called “lying wonders,” such as conjuring spirits “which were only an appearance, and not existing in truth.” This causes one to wonder if ancient feats of flight might all have been faked as a kind of parlor trick. Of course, in modern times, we have all seen the levitation trick known as Balducci levitation, or some variation of it, practiced by street magicians like David Blaine and Criss Angel. While we might be astonished by it at first, a cursory search of the Internet reveals tutorials for performing the trick on Youtube and wikiHow, showing it to be a simple matter of perspective manipulation. Is it possible that Simon Magus and Saint Francis of Assisi and other saints, including the subject of this episode, St. Joseph of Cupertino, might have simply been fooling onlookers? There is a long history of levitation tricks among the more modern hucksters of late 19th- and early 20th-century spiritualism. Mediums like Kathleen Goligher, Eusapia Palladino, and Jack Webber appeared to make objects levitate, and Daniel Dunglas Home actually made a show of levitating himself, but their feats were debunked by skeptics and scientists as frauds. Can the same be said of these saints, and more specifically of St. Joseph of Cupertino, whose numerous flights are well-documented by diarists and Inquisition courts and corroborated by eyewitness after eyewitness? If so, how did he accomplish such a trick? And if not, how can such feats be explained?

A depiction of D. D. Home levitating, via Wikimedia Commons

Giuseppe Desa was born in 1603 in the village of Copertino, into a Kingdom of Naples occupied by the Spanish and under the thumb of the Spanish Inquisition. He was born into poverty, his father a debtor who fled the home rather than face the law, and his mother a strict moralist who raised him in the Catholic Church, offering him so little affection that Giuseppe considered her more of a nurse and thought of the Blessed Virgin Mary as his true mother. Physically abused by his mother and unwell for much of his youth, he focused his mind on his faith and on the stories he heard about St. Francis of Assisi, tales that surely included mention of that saint’s propensity to float in the air during prayer, sometimes higher than the treetops! Giuseppe, or as he’s called in English and as I’ll call him from now on, Joseph began to loiter around churches, acting as an ascetic, wearing hair shirts and was falling into reveries. Despite his clear devotion to the faith, he was more than once denied entrance to the priesthood on the grounds he lacked the dignity they required of their brothers. Eventually he was taken in as a lay brother at a Capuchin monastery, but because of his clumsiness, he was stripped of his habit within a year, leaving the monastery in shame and walking the 90 miles back to Copertino barefoot, where he took sanctuary in a nearby convent’s bell tower like some tragic hunchback. As a favor to his mother, the Conventual Franciscans there took Joseph in as a lay brother, and eventually as a novice. In 1628, at 25 years old, after years of quiet obedience among these Franciscan friars, he became ordained, entering the priesthood on a fluke: the bishop tasked with administering the test to the novitiates was unexpectedly called away, and having found the first few candidates he had tested satisfactory, he passed the rest without a test. On the assumption that this was divine intervention, St. Joseph of Cupertino is today considered a patron saint of students and is frequently prayed to by those who are dreading a final exam.

After his ordination, he sequestered himself in prayer for long stretches of time, and thereafter, his reveries became even more frequent, and he began to claim the first of his supernatural abilities, the gift of prophecy and of “scrutinizing the heart,” or peering into people’s souls to discern the quality of their characters and their hidden sins. Joseph often pronounced judgment on those he encountered and made predictions of what lay in store for them if they did not repent, and it got to the point that his brothers demanded he cease his pronouncements and seek to empathize with the sinners he met rather than denounce them. Thereafter, a new power presented itself; when he lapsed into a trancelike state, or an ecstasy as the friars would have called it, strange things began to happen. He was seen leaving the ground in a kind of levitation, and even taking flight “like a bird.” During Mass or on holy days of the liturgical calendar like Christmas, Easter, and Good Friday, he seemed to rise off the floor and float in place or he was observed leaping to some unnatural height where he would perch himself and remain in his trance until awoken, whereupon he would often need help getting back down. Almost always, his “flights” were preceded by a violent scream or shout from Joseph. Some witnesses have him floating up so that his toes just grazed the floor, while others have him shooting up several inches above the ground, or sweeping forward or backward, or high into the air, sometimes only for moments and other times for 15 minutes or a half hour. Once he is said to have flown up to embrace the feet of a statue that stood more than a man’s height above the ground, and another time he was seen to fly above a church’s main altar to its tabernacle, where he sat among the candles there. He often flew and perched like this. Once, while walking through an orchard and admiring the sky, he flew upward to the topmost branch of an olive tree and had to be helped down with a ladder. Another time, seeing tall crosses being carried in a procession, he became overwhelmed by the question of where he would touch Christ if he had been present at the crucifixion, and he suddenly flew more than three meters from the ground to sit on one of the crosses’ cross-beams and stayed there in a daze until sunset, when, being commanded by his superior to descend, he seemed to come out of his reverie and climbed carefully back down. Over the last thirty-five years of his life, these miracles are said to have persisted and even become more and more frequent and fantastical, with Joseph flying sometimes as high as thirty meters, as he is said to have done in order to admire a painting of Mother Mary, and even to have carried others into the air with him, specifically a mentally ill person, who was miraculously healed during the flight.

“A Miracle of Saint Joseph of Cupertino” by Placido Costanzi circa 1750, via Wikimedia Commons

The church seemed to have conflicting feelings about Joseph’s powers of flight. It seems that some of his superiors likely censured him for his levitation, for Joseph claimed that it caused him shame, and he turned more and more to asceticism and mortification of the flesh to punish his body, which he called “the Jackass,” for its stubbornness and seemingly uncontrollable tendency to fly. His church superiors certainly wanted to keep his levitations more quiet, and they encouraged Joseph’s sequestrations. However, one Father Antonio of Mauro, who had authority over some 60 convents in Apulia, seemed to see Joseph more like a show pony and insisted on taking the flying friar with him during his tour through the region, showing off his amazing displays of flight everywhere they went and building Joseph’s fame far and wide. However, along the way, certain figures in the church felt that Joseph was acting like some kind of messiah, and one finally composed a charge against him for displaying “affected sanctity” and “abusing the credulity of the populace.” Soon Joseph was summoned before the Holy Inquisition in Naples. While some in the tribunal insinuated that the flights were contrived or even satanic, for the most part, they took the reports of his levitation as proof that Joseph genuinely flew and focused on other concerns. After discerning that Joseph did not take pleasure from his levitation, was not proud of them, and could not control them, they pronounced him innocent. For the rest of Joseph’s life after the trial, he was shuffled around, moved to out of the way locations by the church and occasionally called back before the authority of the Inquisition for some further questioning before being maintained innocent and moved again to some place even further remote. In this way, the church treated him like a dirty little secret, much as they have treated confirmed child abusers in more modern times. Never did the Inquisition find him guilty of any crimes, and despite the mortal danger that it put him in, he is even said to have levitated or flew in front of the eyes of his Inquisitors! And as he grew old, hidden away by the church he loved so much, it is recorded that he flew more and more, even in the isolation of his room at a remote monastery in Osimo, where a fellow Franciscan claimed to have seen him float in the air thousands of times. And in the end, it’s said that Joseph knew his time was near, announcing that his body, “the Jackass,” had climbed the mountain and was ready to rest. He died smiling, and “Amen” was his final word.

Much of this story, though, reeks of the exaggeration of hagiography, for the lives of saints are immortalized and made larger than life as a matter of course. However, the process of canonization, at least at the time, also included a strict investigation, by a “devil’s advocate,” of the miracles performed by a saint to confirm they were authentic, with the additional requirement that further miracles occur after the beatified individual’s death, such as miraculous healings after prayer to the prospective saint. After three such posthumous miracles, Pope Clement XIII canonized Saint Joseph of Cupertino in 1767, more than a hundred years after his death. If one were to play the devil’s advocate in Saint Joseph’s case, one could find some support for the allegation that sent him before the Inquisition in the first place: that he was acting like a messiah, or, to take it much further, one might even find support for the notion that he truly was the Messiah come again, an idea that, if we allowed ourselves to credit it, would provide ample reason to believe that he truly did fly and prophesize and read the innermost secrets in the hearts of those he met, for it would mean he was God incarnate, or reincarnate, as it were. He came from a background of poverty, as had Christ, and indeed, much as Christ is said to have been born in a stable, there being no room at the inn where Mary stopped, Joseph of Cupertino too was born in a stalla, meaning in Italian either a stable, a shed, or some kind of lowly stall. Joseph’s father having been obliged to flee because of his debt, his mother had been turned out of her house by debt collectors, leaving her homeless when it was time to bear her child. An intriguing parallel, perhaps. Then there is the fact that, when he made his public debut on tour with Father Antonio, he was 33 years old, famously the age at which Christ was crucified. Indeed, the monsignor who first reported Joseph to the Holy Office in Naples had grown suspicious of him because he was performing miraculous feats and was 33 years old, which seemed itself to be a tacit claim of being the messiah. Now, if one is a believer in the faith, then one believes that Christ ascended with the intention of one day returning to mankind. How ironic would it be, then, if he did return in the 17th century and the Catholic Church hid him away, embarrassed of the miracles he performed. But after all, even if one were disposed to believe such a thing, the evidence is weak. So he was born in a stable; one wonders how many other poor, homeless mothers have sought shelter in stables when it was time to bear their children. Perhaps this was common. And the fact that he was 33 years old when one monsignor saw him fly means nothing if he had been flying since the age of 25.

Depiction of St. Joseph in flight, from the nave of Church San Lorenzo in Vicenza, photo by Didier Descouens, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

If one were to take the job title of devil’s advocate more literally, one might advocate for the extreme opposite view: that Joseph was not the Messiah but rather the Devil, or at least an agent of the devil. The latter seems far more supportable, that he took his power of flight not from a divine source but rather from Satan. Some of his inquisitors suggested as much, and it was certainly a widely held belief at the time that the Devil granted the ability to fly to witches who served him. One reading of his life and career could even be taken to support this story. This version would begin when Joseph was kicked out of the Capuchin Monastery at Martina Franca. Leaving on foot with no shoes or stockings, he later claimed to have been followed by dogs and bandits before meeting a stranger on the road that he believed was Malatasca, a nickname he had for the Devil that meant “Evil Pocket.” This account is extremely vague, but if we unpack it, it seems like the archetypal meeting of the Devil at the crossroads, an opportunity to sell one’s soul in exchange for rewards or good fortune, if you believe such things. One certainly doesn’t need to look far to see what kind of rewards Joseph might have reaped from such a Faustian bargain; after all, he survived the dogs and bandits on the road and soon managed to be accepted at the convent, where through some suspiciously fortuitous circumstances he was ordained a priest without even having to take the test. More than this, Joseph was known to receive gifts supposedly from wealthy relatives and even from mysterious patrons who showed up at his door, giving him new habits and luxury items like fine clothing, art, and watches. Beyond these gifts, there is the obvious gift of flight, and it is said that when he used his gift of “scrutinizing hearts” and of prophecy, that he did so rather more like a sorcerer than a holy man, predicting that sinners or people who had crossed him would suffer pains or afflictions, making it seem like he was cursing them using some kind of black magic. This perspective of Joseph and his abilities also breaks down under examination, though, for Joseph was ever an obedient priest, casting aside the luxuries he enjoyed and denying himself worldly comforts to make up for his sinful indulgence in them. Moreover, he seems only ever to have used his powers to encourage faith in the Catholic god, rather than to lead any of his flock astray. There are even stories of him confronting and condemning those who practiced sorcery. If he was an agent of the devil, he concealed it very well and seems to have never accomplished much for his diabolical patron.

Today the notion of a devil’s advocate is more of a rhetorical device, to entertain a critical viewpoint for argument’s sake. Therefore, let us return from our sojourn into religious views of this figure to the realm of science, skepticism, and critical thought to determine whether, as even some of his Inquisitors suspected, Joseph was perhaps a fraud. The loudest voice advocating a skeptical view of the saint comes, as is frequently the case, from noted skeptic Joe Nickell, who does a close reading of philosophy scholar and critic of the materialist worldview Michael Grosso’s book, The Man Who Could Fly: St. Joseph of Copertino and the Mystery of Levitation. Grosso’s book is also my principal source, as he did the important work of having old Italian works about the saint translated into English and therefore offers the most information on St. Joseph’s life. Nickell looks at the material Grosso presents and points out a few key passages as evidence that Joseph was conning everyone. First, he looks at descriptions of his levitation and suggests that when the priest was floating just above the floor in his robes or gliding forward or backward, he was likely creating an illusion by rolling back from resting on his knees to resting his buttocks on his heels, which would look like he was rising off the ground while kneeling. Furthermore, his higher flights can all be explained, according to Nickell, as leaps or bounds made by a clearly very athletic man, pointing out that every time he “flew” to a great height, he did not hover in the air but rather was obliged to grab onto and perch on something. He suggests that the fact Joseph cried out every time he supposedly flew was evidence that they were acts of athletic prowess, requiring great physical effort and eliciting a cry like that of a martial artist striking boards. And he even looks at some of the accounts of Joseph’s life that Grosso has included to suggest some acquaintances knew him for a fraud, such as a companion who had traveled with him for years eventually requesting to be sent away, or Father Antonio, the prelate who had taken Joseph on tour, saying nothing about his ability to fly when asked about Joseph years later. Altogether, it is a very convincing argument, but as with many skeptical arguments, it has serious flaws that a sincere skeptic probably should have acknowledged.

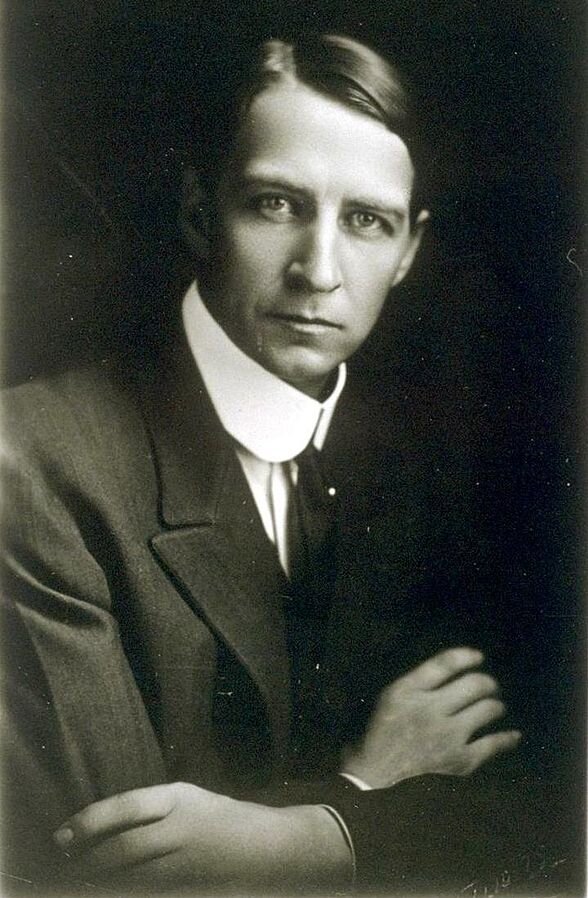

Saint Joseph of Cupertino (Copertino). Engraving by G.A. Lorenzini. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Among the biggest problems with Nickell’s reading of the facts is that so very many people witnessed and gave clear testimony about Joseph’s ability to fly. Thousands saw his feats, and the written records in court depositions, biographies, letters, and diaries are numerous. Perhaps some of these could be dismissed as poor observers taken in by an illusionist, but could all of them? None record any detail to cast doubt on his flights, and in fact, many describe him not as seeming to float or leaping high, but rather soaring like a bird. Indeed, it is the skeptic Joe Nickell who appears to be dismissing great swathes of the testimony on the assumption that they were fooled or moved by faith and the power of suggestion to give the reports they gave. Moreover, if Joseph were the skilled illusionist that Nickell suggests he was, that would have made him an ingenious and extremely deceptive charlatan, and that just simply isn’t the character we see in what survives of his life story. He appears to have been meek and dutiful with his superiors, and to have preferred isolation. Rather than reveling in his displays, they seem to have caused him great distress. Moreover, he seems to have been far too weak of intellect to have maintained such a deceit for so long. Growing up, he was certainly believed to be stupid, even having earned the nickname “gaping mouth” for the way he always went about with his mouth hanging open. As previously discussed, he became the patron saint of students only because he was so terrible in his studies and only lucked through exams. Could such a dullard have possibly made fools of everyone he encountered? And if he was truly so secretly clever, why on earth would he have persisted in pretending to fly even in front of his Inquisitors when he would have known that it put his very life in danger?

The skeptic Joe Nickell would further have us believe that Joseph accomplished his illusions by sheer physical prowess, exerting the bodily control of a yogi in balancing just so beneath his robes, or by displaying the strength and grace of an acrobat in leaping to great heights and balancing on precarious places. In truth, it seems that Joseph of Cupertino was not so physically gifted as this. As a child, he was bedridden by a growth the size of a melon on his behind. After it was eventually removed by surgery, he had a difficult time walking, let alone bounding and leaping, and because of this, he grew into a remarkably clumsy young man. In fact, it was this oafishness that led to his being stripped of his habit by the Capuchins: on kitchen duty, he knocked over boiling water when he put wood on the fire, and he broke many dishes. As if this weren’t enough, he even punished his body with his ascetic practices. A hair shirt wasn’t enough for penance, he thought, so he put the broken pieces of the dishes he dropped inside his shirt to cut his skin. Such behavior would continue throughout his life, as he devised unique ways to rend his own flesh, building his own scourge with needles and pins and sharp pieces of steel, and he wore a chain with spurs tight over his shirt throughout the day. He distressed his superiors by covering his body with lacerations in this way. Once he even knelt praying for so many hours that his knees became infected, and Joseph decided to cut the infection from his own flesh with a common knife, which of course led to another lengthy convalescence like in his youth. This simply does not sound like a man with the physical strength to accomplish the feats of acrobatics that Nickell suggests he pulled off, like leaping some six feet into the air to grasp the feet of a statue and through massive upper body strength hold the rest of his body out parallel to the ground. But some may be inclined to disagree, suggesting his illnesses only made him stronger and asserting that his mortification of the flesh bespeaks a great strength of mind. In that case, consider this: his levitations and flights are said to have continued to the end of his life, when he was a 60-year-old man sequestered in a remote monastery with only a few fellow priests there to impress. Even if a 60-year-old could pull off these tricks, what would have been the point?

Yet another 18th century depiction of San Giuseppe da Copertino, via Wikimedia Commons

In the end, as devil’s advocate, I find it hard to advocate for any argument thus far. I cannot accept that he was a black magic sorcerer or that he was imbued with some godly power, yet neither do I find the rationalist skeptic’s explanation convincing. And what are the alternatives? One could claim that his legendarium is a result of a massive conspiracy by the church to produce a saint who would be used to propagandize, but this is untenable—as are all massive conspiracy claims—and easily disproven by the facts of how the church actually treated him. Or is it possible that all of this is a huge misunderstanding due to mistranslation and historical distance preventing our understanding of the idiom of the time? Many of the reports of Joseph’s flights don’t use the word for flying or flight, using instead the word ecstasy, which as I mentioned before is meant to indicate the reveries during which Joseph was said to have flown. The word ecstasy refers to being outside of oneself, displaced from the body in a trance of exaltation. It derives from Ancient Greek ἐκ, or “out,” and ἵστημι (hístēmi), “to stand,” so literally being beside oneself, and use of the word may explain another supposed superhuman ability of saints, bilocation, or being in two places at once. It is tempting to suggest that the use of this word, which only referred to being in a rapturous stupor, has led to the misunderstanding that Joseph was flying around. His Inquisitors, after all, questioned him about his moti, the movements of his body, which seems like it could just as well refer to any movement he made during a trance. But this explanation too would be a weak refutation only capable of convincing someone who wanted to believe the saint to be a fraud. It is a simple thing to cast doubt on the work of experts, like the translators of historical documents who have provided us so much clear first-hand testimony of Joseph’s supernatural abilities of flight. That is the practice of a denialist. I cannot double check their translations, and others who know better have done so. Thus I find myself scratching my head, actually wondering if it’s possible that a man could fly. After all, we have examples of seemingly superhuman feats from people in other monastic traditions, like Tibetan monks who raise their body temperature in order to withstand great cold. If science can accept the mind’s ability to influence the body, then will it someday accept that this influence could go so far as to enable the body to break the laws of physics? As Sherlock Holmes said, “[W]hen you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth”… but what happens, I wonder, when the impossible can no longer be eliminated?

Further Reading

Nickell, Joe. “Secrets of ‘The Flying Friar’: Did St. Joseph of Copertino Really Levitate?” Skeptical Enquirer, vol. 42, no. 4, July/Aug. 2018. Skeptical Enquirer, skepticalinquirer.org/2018/07/secrets-of-the-flying-friar-did-st-_joseph-of-copertino-really-levitate/.

Grosso, Michael. “Evidence of St. Joseph of Copertino’s Levitations.” Esalen, www.esalen.org/sites/default/files/resource_attachments/Ch-1-Supp-Joseph.pdf.

Grosso, Michael. The Man Who Could Fly: St. Joseph of Copertino and the Mystery of Levitation. Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.