The Erasure of Aspasia

As I’m sure is the case with many of you listeners, my head has been spinning, my faith in humanity plummeting, and my existential dread rising like bile in my throat over the last month or so since Trump took office and started his deplorable shock and awe campaign. I feel compelled to comment on this, even though I was not planning to address current politics directly so soon this year. I like to have a buffer between episodes with explicitly political commentary in the podcast, so that not every episode ends up a political diatribe, since I often get negative feedback when I do get political and it causes me to question whether I should broach such topics at all, even though it has been a focus of my content from the very beginning, and even though my official podcast description makes clear that I use history to gain insight into modern political culture, and even though I have actually officially categorized the podcast under politics. Now, though, I honestly don’t really care if I turn off some listeners. Any listeners that might bristle at my comparison of Trumpism to fascism and then try to rationalize when Elon Musk overtly Sieg Heils at Trump’s inauguration and Steve Bannon follows suit with his own stiff-arm salute at CPAC, are just lost to reason, and I don’t care to take their objections seriously anymore. They truly are obeying the “final, most essential command” of the authoritarian, as given by the Party in Orwell’s 1984, “to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears.” But the theme and purpose of this show is the examination of history that has been distorted, misrepresented and mythologized, and not every political issue relates to a specific historical topic that fits the show’s theme, or at least apt historical analogies do not always come to my mind. Therefore, I often don’t address political issues in a very timely manner. Nor does my timing always work out the way I’d like it to. No one is more disappointed than me in the podcast’s shortcomings in that regard. For example, considering Trump’s current assault on all efforts to address systemic racism through initiatives designed to encourage diversity, equity and inclusion, I thought it would be important to devote some topics to Black American historical figures for Black History Month. I haven’t typically devoted February topics to celebrating Black history, again because strong topics fitting the show’s theme haven’t always occurred to me at the right time, and I wanted to start this year—I even had some topics in mind. It seems especially important since, despite still proclaiming February Black History Month as presidents always do, Trump’s anti-DEI executive orders have had a chilling effect on its celebration, even leading the Department of Defense to forbid the observance of any “identity months.” However, I also wanted to cover my recent topic about Lincoln in February, to coincide with Lincoln’s birthday. So instead, I started my Lincoln topic in January, and the series just ended up ballooning and becoming four parts that took up all of February as well. I still hope to revisit the Black history topics I had in mind in the future, whether in February or not, but now, as we enter March, I think it important to observe Women’s History Month, since women’s rights are under such clear assault by the right. Even between his respective terms in office, Trump’s appointments to the Supreme Court and right-wing judicial activism have resulted in women losing long-settled reproductive rights and body autonomy when Roe v. Wade was overturned, and there are indications that the right are coming for the morning-after pill next, and maybe even birth control access generally. More than that, Trump has revoked protections against sexual misconduct in schools and in the workplace, unsurprising considering the long history of such allegations against the president himself. Following the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 playbook like an instruction manual even though he distanced himself from it during his campaign, Trump has been clear that he won’t work to better ensure equal pay for women or to improve maternity leave and paid family leave laws, and that generally he thinks pregnancy is more of an inconvenience for employers. Some Christian Nationalists associated with his administration have even advocated for rolling back women’s right to vote in favor of a “household vote,” which just means male-only voting. House Republicans actually passed a bill requiring that voters have a birth certificate or passport matching their name, which seems designed to disenfranchise the estimated 69 million married women who took their husband’s name and have no passport. Clearly when he envisions making America great again, he conceives it as a regression to a time when women’s rights and roles were circumscribed, when they were subordinate in the workplace and at home. Even as I am finalizing this episode on March 6th, Trump just signed a proclamation declaring March Women's History Month, something every president has done since 1995. But when Trump signed it, saying "Women, we love you," it drew criticism, because he is clearly only paying lip service to women’s rights in the midst of and despite his ongoing war on women. In fact, even as he signed it, he and those around him managed to take the focus off of women and put it on him. He had one of his female lawyers, Lindsey Halligan, hand him this proclamation, saying it was in honor of the women in America, sure, but more specifically, the women in his administration, and "in honor of everything you've done for women." Trump smugly responded, asserting he's done a lot for women, and framing the accomplishments of women everywhere as valuable insofar they do it "for us." But that is just exactly the issue with the erasure of women, that they have, historically only been seen as relevant inasmuch as they serve men. So for my first episode of March, I want to tell the story of one woman, far back in antiquity, who was also treated as a second-class citizen, who was sexualized and seen as troublesome for her influence in politics, and who was almost erased from history, but whose memory nevertheless persisted, and who today is remembered also as a brilliant rhetorician and teacher—a pillar of Greek philosophy. As feminist historian Rebecca Solnit writes, “Some women get erased a little at a time, some all at once. Some reappear.”

Historical erasure is a concept that perfectly encapsulates the Historical Blindness theme. In some sense, erasure can be a natural part of the building of cultural identity, the process by which some people and events fade in the collective memory while others are remembered and celebrated or scorned. This is not to say that power structures aren’t involved in this natural winnowing of the past—they are—but sometimes this erasure is even more insidious: the distortion of history to serve one’s ideology, the purposeful misrepresentation of history, the invention of pseudohistory, the outright denial and negation of history. These are all forms of erasure, and it is the ideal goal of the historian to expose such falsehood, to fill in gaps, to recover forgotten history and therefore reclaim that which has been systematically erased from historical memory. And part of that requires us to expose the power structures that result in this erasure, for it is inevitably marginalized and disadvantaged groups that disproportionately suffer erasure, whose historical erasure is actually a principal feature of their marginalization. Thus we see that historical and cultural erasure is a prominent feature of genocide, as can be seen with colonial attempts to expunge indigenous peoples, Nazi attempts to wipe out Jews, not just from existence but even from memory. And the historical erasure of women stands even more prominent, spanning all cultures and all history. The contributions and accomplishments of a great many women in every culture, every region, every time period, have gone unrecorded, have been minimized or ignored, or as is most common, are attributed to men instead. A brief list should illustrate the point: nuclear particles, the double-helix of DNA, dark matter, microbial genetics, nuclear fission, pulsars, brain receptors, and computer algorithms were all momentous scientific discoveries or developments made in modern times by women that were wrongfully attributed to men. But as ubiquitous as this erasure is, it is even more pronounced the further back in time we look, when surviving records are rare because of the rarity of literacy, and women more often left no record of themselves, for those who wrote what records we have were men who thought them less worthy of remembrance. This is an erasure of the history of half of humankind that should be mourned. As we look at antiquity and ancient Greece, the only reason we are able to talk about Aspasia and reclaim her memory to whatever degree may be possible from the 5th century BCE is because more of a biographical tradition exists about her than any other woman, with perhaps the exception of the 6th-century poet Sappho, and no women of the ancient world would again have her life spared such erasure until Cleapatra in the first century BCE. Just three women whose lives were preserved in any substantial way by history over the course of 500 years, and as we will see, even then only sketchily and dubiously, with conflicting reports that make of her either a scheming prostitute or respected philosopher.

A 1920s depiction of Sappho, one of the only other women whose biographical traditions survived ancient Greece. Patrons on Patreon can hear an exclusive episode all about her.

Very little can be known for certain about Aspasia of Miletus. Most of what is known or assumed to be true about her was written hundreds of years later by philosopher and historian Plutarch in his Parallel Lives, a series of biographies. But more specifically, Plutarch’s comments on the life of Aspasia were contained within his biography of Pericles, the famed Greek general and politician during the Golden Age of Athens, with whom Aspasia was sexually or romantically or matrimonially involved, and whose illegitimate son she is said to have borne. So the most coherent account of her life was written centuries later, by a man who was actually only writing about her insofar as she was associated with another man, a very famous man, in fact, about whom much had already been written, including by his contemporaries, like Thucydides, who called him the “first citizen of Athens.” In fact the period during which he ruled Athens as its Archon, forging an Athenian empire of the confederate states of the Delian League and leading it in multiple wars against Sparta and its Peloponnesian League, has even been called “The Age of Pericles.” Meanwhile, the only contemporary writing about Aspasia came in the form of defamatory comedies, which we will look at shortly. Indeed, it is because of the claims about Aspasia’s power over Pericles, because of the claim that Pericles only took Athens to war on her behalf, that Plutarch even deigns to discuss her, saying, “this may be a fitting place to raise the query what great art or power this woman had, that she managed as she pleased the foremost men of the state, and afforded the philosophers occasion to discuss her in exalted terms and at great length.” Plutarch seems torn between more than one competing tradition regarding Aspasia, presenting her as a political mastermind and revered philosopher and also as a brothel keeper and sex worker. I am not here to suggest that a woman could not have been all these things, but as we will see, these conceptions of her do seem to have been derived from differing views of her and were, at least then, seen as contradictory characteristics. Even Plutarch’s brief discussion of her can’t seem to decide if Pericles was drawn to her intelligence or was attracted for more carnal reasons, saying first that she “was held in high favour by Pericles because of her rare political wisdom,” but then asserting that “the affection which Pericles had for Aspasia seems to have been rather of an amatory sort.” Again, it could have been both, but the original Greek, which has the word translated as “rather” nearer the beginning of the sentence, and in alternative translation seems to suggest an erotic attraction, can be understood as suggesting that rather than an intellectual admiration, Pericles’s love for her could be better described as sexual. However, any such assertion, as we will see, cannot be supported.

According to Plutarch, it “is generally agreed” that Aspasia was a foreigner to Athens, Milesian by birth, and the daughter of one Axiochus. This made her, by Pericles’s own laws on Athenian citizenship, a metic, or resident alien in Athens, denied the benefits and protection of a full citizen, including the ability to marry a citizen. This means that some early accounts of Aspasia that style her as Pericles’s wife are inaccurate, as she could at best have been considered his pallake, or concubine, a fact further attested by the tradition that the son she bore Pericles, called Pericles the Younger, was a nothos, or illegitimate child. Some historians, like Peter Bicknell, and my principal source, Madeleine Henry, in her book Prisoner of History, consider these details about her life at least mostly established by the discovery of a gravestone or stele in Piraeus, an Athenian port city known to have been a place where metic families settled after immigrating to Athens. This stone actually commemorates a man named Aspasios, but its inscription names a forebear called Axiochus, and mentions his children, one of whom was named Aspasia. It also identifies Axiochus as the son of Alcibiades—not the famous Alcibiades, the Athenian statesman of the later fifth century, but his grandfather, an elder Alcibiades who had been ostracized and exiled, probably to Miletus. Since this noble family can be traced to Miletus, where the elder Alcibiades seems to have had children with a Milesian woman, and since the names Axiochus and Aspasia, which would be mentioned by Plutarch centuries later, appear here within the same family even though they were rare names, not known to have been in use at all in the region before the next century, it has been concluded that this proves Aspasia was an aristocratic metic woman from Miletus, born sometime after 470 BCE, who arrived in Athens sometime after Alcibiades’s exile ended, circa 450 BCE. It should be noted that even this is uncertain, though. The Axiochus and Aspasia mentioned on the monument aren’t even thought to be the same ones Plutarch names. Instead, it is thought that Alcibiades married the daughter of a Milesian man named Axiochus, and the Aspasia in question, who would go on to make such waves in Athens, was his wife’s sister. The names Axiochus and Aspasia thereby became family names, as Alcibiades named one of his sons Aspasios, the masculine form of his sister-in-law’s name, and his other son he named Axiochus after his father-in-law, and by him would be given a grand-daughter that would be named Aspasia as well. It’s all very convoluted, and the fact that Aspasia’s parentage and origins can only be pieced together through detective work, based on the funerary monument of a male relative, which doesn’t even mention her by name, just goes to show how nearly entire her erasure was.

Bust of Pericles, circa 430 BCE.

With some corroboration of the claims that Aspasia was a metic, or resident foreigner in Athens, it is possible to ascertain some truths about her life, the obstacles she had to overcome, and the nature of her relationship with Pericles. Pericles’s law on citizenship, which was passed around 450 BCE, denied full citizenship rights anyone whose parents were not both Athenian. The law was passed in response to an influx of immigrants in the wake of the Persian Wars. The word metic meant, literally, “home-changer.” Denying citizenship to these immigrants meant that they had all the responsibilities of citizenship, including mandatory military service and taxation, with none of the benefits. They could not own property, were not eligible to accept certain state benefits, such as work opportunities and emergency rations, and were barred from serving in juries and the assembly—essentially refused the right to vote. They did not enjoy the same protections under Athenian law: they were subject to additional and more onerous taxes than citizens; they could be tortured; they could be enslaved; and the murder of a metic did not carry consequences as severe as did the murder of a citizen. If Aspasia did indeed arrive in Athens with her family at around the time scholars think she may have, for the reasons already discussed, it means that this law was brand new and the subordinate status that it forced on her and others in her family may not have been expected. However, unlike many other metics, who were former slaves and impoverished artisans, Aspasia seems to have come with a well-off family, so wealth may have shielded her from some struggles. For example, metics coming to Athens had to be sponsored by a citizen, otherwise all their belongings could be taken from them and they could be sold into slavery. If indeed she was the sister-in-law of the elder Alcibiades, who was returning to Athens a citizen after his exile, then this draconian aspect of the law would not have affected her. However, we must also remember that she was a woman, and thus doubly marginalized, made a second-class citizen on both counts. Even if she were not a metic, she would have been unable to participate in politics or own property as a woman. As has been the case in so many cultures throughout history, women in ancient Athens were expected to devote themselves solely to men. Under the kyrieía, or guardianship, of male relatives during their youth, they were the property of men, and once their marriage was arranged, they became the property of their husbands. However, as a metic, Aspasia was also denied the right to marry a citizen, which further limited her opportunities.

As already mentioned, Aspasia’s relationship with Pericles has sometimes been characterized as a marriage, though according to Pericles’s own law, it could only have been a de facto marriage, with Aspasia only his pallake, his mistress or concubine. Pallakia was a common practice and was even institutionalized in a way similar to marriage. Some historians have suggested that pallakia was even quasi-marital for metics, because metic women were also under the guardianship of their male relatives, whose main obligation was to arrange an advantageous marriage for them, and for many, especially those like Aspasia from an aristocratic family, that may have meant arranging concubinage to a wealthy citizen rather than marriage to another metic, especially if it were to Pericles, the most powerful man in Athens. There is some evidence of pallakia being entered into as a contract, with protections for the woman, making it essentially a marriage in all but name. However, since the citizenship law was so new when Aspasia became involved with Pericles, it is less likely that such an arrangement may have been made. Still, it may have been that she chose the role of concubine instead of wife because it granted her the protection of this powerful citizen but allowed her more freedom, since more domestic duties may have been expected of a wife. As one speech attributed to an Athenian politician explains, “Mistresses [sometimes translated as “prostitutes”] we keep for the sake of pleasure, concubines for the daily care of our persons [sometimes translated as “the body’s daily needs”], but wives to bear us legitimate children and to be faithful guardians of our households.” Therefore being Pericles’s pallake may have meant that she was spared the daily duties of a wife and rather given the opportunity to develop her mind, which would accord well with the tradition that she was extremely intelligent and became an influential philosopher. Further supporting this notion that Pericles may have not only offered her protected status as his concubine but also nurtured her, in a sort of evolved and mutually supportive relationship, is the tradition that Pericles loved her “exceedingly,” as Plutarch put it. And there is support for this claim as well. Around the same time he took up with Aspasia, he divorced his wife, the mother of his two legitimate sons, and gave her in marriage to another man. This contributes to the notion that Aspasia was his de facto wife, whether or not his own law allowed a legal marriage with her. Then there is the fact that he remained with Aspasia for the rest of his life, and the further fact that, before his death, he amended his citizenship law so that Pericles the Younger, his illegitimate son with Aspasia, could become his legal heir. Alternative reasons exist for this amendment, such as that his two legitimate sons had died in a plague and many other citizens had likewise lost their legitimate heirs in the plague and the Peloponnesian War. There is also the fact that Aspasia entered a relationship with another politician immediately after Pericles’s death, but the details of this arrangement are unclear, to the point that some historians doubt it happened. The fact is that, the only contemporary sources about their relationship, the sources Plutarch relied on, were political comedies satirizing her and Pericles, many of these details are entirely dubious.

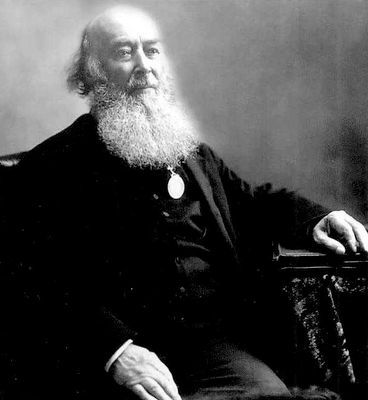

Frontispiece to a 1656 printing of Lives of the Noble Grecians & Romans by Plutarch.

It appears that the bulk of Plutarch’s account of Aspasia is derived from fifth century comedies, the only contemporary sources that speak of her, of which only a handful make mention of her. As an exception, Plutarch makes special mention of a supposed trial, in which one Hermippus prosecuted Aspasia for “impiety,” a trial in which Pericles himself was said to have “shed copious tears” in her defense. Certainly, if true, this would be further evidence of Pericles’s great love for her, but scholars now believe that this trial was a fiction. Hermippus was a comic poet, and it is well-established that comic plays sometimes adopted the language of courts and were even thought of as a kind of trial in which the audience acts as a jury, such that talking about a comic poet “prosecuting” major public figures more than likely meant that Hermippus simply put the two of them on blast in one of his plays. The specific allegations of this supposed trial, that Aspasia was acquiring prostitutes for Pericles’s pleasure, also wouldn’t appear to have been an actual crime, since prostitution was legal. Moreover, the accusations of politicians being pimps and whoremongers, or of being profligate and licentious, were common allegations in political satires of the era, and sometimes may not even have been literal. Just as today, when likening politicians to prostitutes may not mean that they literally are prostitutes, in the comedies of fifth-century Athens, just as we cannot presume that a “prosecution” was a literal court trial, we cannot presume that accusations of prostitution were about literal sex work. And this is the sole evidence of Aspasia’s alleged sex work. The comic playwright Aristophanes would be the one to really emphasize Aspasia as a prostitute, and he was known for using prostitutes as symbols of corruption and of death and destruction. Think of the biblical Whore of Babylon for an example of how sex workers have always been used as metaphors for the criticism of corrupted nations and leaders. As a more pertinent example, the poet Cratinus, in calling Aspasia a “dog-eyed concubine,” is thought to have been likening her to Pandora, the first woman, thought to have been a curse upon mankind, who had been given the power of speech only to deceive, and who it was said had the mind of a disloyal dog. Clearly such comparisons make it plain that her depiction in plays were slanderous and not to be taken literally. And there are logical reasons to doubt any claims that she was a prostitute. While it is true that many prostitutes were metic women, since they often had few other options to pursue in life, and while it is also true that prostitutes sometimes became the concubines of their former patrons, making it possible that Aspasia had been a prostitute before taking up with Pericles, it is hard to reconcile with the fact that she seems to have come from a wealthy family. Moreover, the fact that her son was recognized legally as the son of Pericles makes it impossible that she was a prostitute during their relationship, since the paternity of any prostitute’s child could not be proven. So any and all claims of Aspasia’s being a prostitute must be viewed skeptically, as potentially just another way that the real Aspasia was systematically erased from public memory.

Aspasia seems to have been so lampooned in political comedy because of her perceived influence over Pericles and his decisions, and it would seem that this fact supports the tradition that she was highly intelligent and that Pericles did respect her intellect. Much of the political comedy that defamed her and resorted to the potentially metaphorical accusation of her being a prostitute portrayed her power as being purely sexual. They did this by comparing her to mythological female figures who were known for manipulating and sexually dominating men. The playwrights Cratinus and Eupolis explicitly compare Aspasia to Omphale, the mistress of mythical hero Heracles, sometimes better known by the Romanized name Hercules. According to the story, Heracles was forced to be the slave of Omphale for a year, so the implication here was that Pericles was the slave of Aspasia, and perhaps that he had lost his manhood to her, as later depictions of this myth have Heracles dressed in women’s clothing and forced by Omphale to do “women’s work.” Another common comparison was to Helen of Troy, with the implication that, because of Aspasia’s great beauty and Pericles’s obsession with her, he had, like Paris before him, started a war. The war in question was either the Samian War, an Athenian military intervention in a conflict between Samos and Aspasia’s birthplace, Miletus, or the Peloponnesian War, more specifically, that the Megarian decree that imposed economic sanctions on the Spartan ally Megara and led to the war was because of her. Aristophanes is very explicit in blaming this on Aspasia’s influence, claiming that some Athenians abducted a prostitute from Megara, and in retaliation some Megarians kidnapped two of Aspasia’s own prostitutes. This is actually the origin of claims that Aspasia was not only a prostitute but also a brothel-keeper or madame. Scholars are divided over whether the Megarian Decree had purely economic motivations, whether it was in response to the Megarians cultivating some sacred land on Athenian borders, or whether Pericles meant it as a deliberate provocation of Sparta, but none take seriously this passage in Aristophanes’s play, which is thought most likely to be a joke. Nevertheless, this idea that Aspasia had enough power over Pericles to force him to declare war led to the further claim, repeated by Plutarch, that Pericles went to war against Samos on her behalf, even though the most obvious reasons were that Athens had forced Miletus to disarm itself after it had risen in rebellion against them, so it would look bad if they then let Samos move in and capture the city. But whatever the practical reasons, it seems to have been simpler and more popular to blame these geopolitical affairs on the woman behind the man. By Plutarch’s time, he was making still more comparisons, claiming without any clear reference to sources, that Aspasia had modeled herself on an Ionian courtesan named Thargelia who was said to have dominated Persian politics through her beauty, grace, and wits, and also by providing consorts for the Persian king. It is clear that Plutarch, writing more than 500 years after the fact, had accepted the claims made in Greek comedy, perhaps jokingly and metaphorically, of Aspasia’s prostitution, brothel-keeping, and sexual domination and manipulation of Pericles. But there was another tradition about Aspasia, one Plutarch mentions but does not emphasize.

A 19th century painting depicting Aspasia teaching Socrates rhetoric.

The only thing Plutarch says of Aspasia’s reputation as a philosopher is that Plato mentioned Aspasia “had the reputation of associating with many Athenians as a teacher of rhetoric,” though he is quick to suggest that this may have been “written in a sportive vein,” a caveat he failed to provide when sharing the obviously defamatory and probably metaphorical claims of satirists who called her a whore. This is, however, entirely true. The work of Plato’s that depicts Aspasia as a master rhetorician does so with ironic and satirical purpose, and this is because some 4th century Socratic dialogues were still defaming some of the same historical figures as fifth century comedy, still making them the butts of their jokes and the focal points of their criticism. This genre of philosophical prose writing centered on the wisdom of Socrates, as depicted in conversations he had with various individuals, which displayed his Socratic method of asking rhetorical questions in order to lead his interlocutors to conclusions. Aspasia herself was never a character in them, that we know of, but more than one was named after her. To illustrate her continued negative portrayal in Socratica, Antisthenes, himself an illegitimate son and contemporary of Aspasia’s son, Pericles the Younger, wrote a dialogue named after her. It is lost now, but it appears to be the origin of the story that Pericles wept copiously in her defense, and also of the story that Pericles was always publicly embracing Aspasia, and that this was the origin of her name, which meant “Miss Embrace.” Certainly these were meant to be criticisms of Aspasia’s sexual dominance of Pericles, as Antisthenes was known to be always attacking Pericles and his family. Unlike Antisthenes, who seemed rather stuck in the past when it came to defaming Aspasia, Plato did so with far more nuance. Like others, he had Socrates talk about Aspasia like an honored rhetorician who teaches rhetoric to others, and portrays her skill and intellect as well known, for it is presented as well-established that she taught rhetoric to Pericles, who was the most influential man in politics. The dialogue in question is called Menexenus, in which the title character approaches Socrates because he desperately needs an epitaphios, or funeral lamentation, to honor the Athenian war dead on short notice, and Socrates says he has just the speech for him, given to him recently by Aspasia. By the date in which the scene is set, both Aspasia and Socrates would likely have been dead, so like the comedies of the previous century, it cannot and should not be taken as historically accurate, and it is abundantly apparent that Plato’s purpose is not to honor Aspasia. It is with great irony that, when asked for a speech to honor male Athenian citizens, Socrates gives Menexenus the words of a woman who was denied citizenship. The dialogue is considered a parody of the genre of the epitaphio, which often sought to define what it meant to be Athenian based on autochthony, or the fact of being indigenous, a nativist idea that was mocked by Antisthenes by saying snails and locusts too must have been citizens, since many had been born on Attic soil. The fact that Plato attributes a speech about birthright citizenship and manly courage to a female non-citizen, would seem to undermine its message. But there is more going on here. Socrates suggests that speakers are interchangeable, that what matters is the words, and he suggests that it was Aspasia, the writer of these words that so impress Menexenus, who taught the great Pericles to speak, as well as many others. Add to that the fact that Plato seems to include a great deal of sexual innuendo in the language, the known fact that she was sexually involved with Pericles, and the insinuation, as some scholars interpret the dialogue, is that Aspasia must have been sexually involved with all the men she taught, and that through the influence of her sexuality, she was putting words in the mouths of many great speakers and politicians. Taken this way, even Plato’s work partakes of the same tradition of depicting Aspasia as a Machiavellian sex worker. But there are some aspects of Plato’s dialogue that highlight the alternative biographical tradition then emerging: he very clearly presents Aspasia as a masterful orator and rhetorician, as a teacher of many prominent Athenians, and as a mentor to Socrates himself, one of the greatest philosophers of all time. Moreover, the fact that Menexenus responds knowingly to Socrates’s statements about Aspasia make it clear that these aspects of her life were actually well-known and widely accepted.

It seems that the first philosopher to portray Aspasia in an entirely positive light was Aeschines, a contemporary of Plato. In his Socratic dialogue, also called Aspasia and perhaps meant as a direct response to Antisthenes’s negative dialogue of the same name, Socrates is approached by an affluent man named Callias and is asked to recommend a teacher who can instruct his son. Socrates recommends Aspasia and then goes on to give reasons why Aspasia is an excellent teacher. The dialogue is now lost, except for fragments, but through references to it, it has been credibly reconstructed. It seems that Socrates started by giving historical examples of women who were brilliant and made excellent teachers of men: one being Rhodogune, the Amazonian queen of Persia, and the other was Thargelia, the Ionian courtesan previously mentioned. This reference may be the source for Plutarch’s claim that Aspasia modeled herself after Thargelia, but that is not what Aeschines seems to have claimed, and in fact he may have been suggesting that Aspasia made for a happy medium between the two, one a warrior queen and the other, who wielded influence over kings through sex. Some have tried to interpret this dialogue as further depicting Aspasia as a prostitute, suggesting that in asking for a teacher for his son, Callias was actually asking for a woman to teach him sexual techniques, but this interpretation doesn’t conform to the rest of the dialogue as we know it. First, it is set during a time when Aspasia would have been an old woman, making it seem far less likely that she would be recommended as a sex tutor for a young man. And Aeschines does not seem to have represented Aspasia as leveraging her beauty and sexual appeal at all. Rather, she was presented by Socrates not as the consort of Pericles, but as his educator, and he her best student. Moreover, it is revealed that Aspasia was a teacher of many Athenian women as well, and respectable Athenian women at that, making it very unlikely that she would have been engaged in prostitution or brothel-keeping at all. Rather, the dialogue makes it sound as if Aspasia ran a sort of academy for women, educating them in politics, rhetoric, and philosophy, something that was frowned on if not outright prohibited. Some scholars have suggested that this may have been the origin of the defamatory claims that she ran a brothel, for it was easier to dismiss educated women as whores and discredit the place of their learning as a whorehouse than it was to acknowledge that they were just as capable of thinking as men.

Marie Bouliard's 1794 portrait of Aspasia, incorporating more than one view of her.

As the dialogue went on, Aspasia is described as giving specific marital advice to one Xenophon and his wife, and the format that this advice takes is the Socratic method, asking the couple rhetorical questions intended to lead them to a realization about their expectations in the relationship. This explicit example of Aspasia’s intellect and discernment is proof that Callias wasn’t seeking erotic tutelage for his son, for why would Socrates recommend Aspasia for that purpose on the basis of her ability to give sound advice and demonstrate sound reasoning? Since Socrates acknowledges her as his own teacher, it also suggests that the Socratic method should be named after her instead: the Aspasian method. And the very fact that the person in the example, Xenophon, was himself a real person and a philosopher who would go on in numerous works to espouse the great wisdom of Aspasia, especially in giving advice about relationships and household management, seems to lend credence to the idea that Aeschines was indeed portraying her in an accurate light. Nevertheless, by the time Plutarch wrote about her, hundreds of years later, it is apparent that of these two competing traditions, of Aspasia as a sage or a whore, the latter had won out. And over the centuries since, the two traditions would continue to vie for dominance. In the Middle Ages and early modern periods, she was portrayed variously as Pericles’s sexpot concubine or as a teacher and philosopher, furthering this false dichotomy. And rarely were the two views of her reconciled, rarely was it ever suggested that she might have been both a genius and sexually empowered. Only one eighteenth-century portrait of her illustrates these typically conflicting conceptions of Aspasia united, portraying as a great beauty, one breast bared, but rather than looking out at the viewer of the portrait, she is gazing into a hand-held mirror. This may be taken to represent vanity, but it can alternatively be viewed as showing her focus on self-actualization. And in the same painting, in her other hand, she holds a scroll, clearly symbolic of learning. Of all the portrayals of her, this may be the most balanced, even if it may still be entirely inaccurate. During the same century as this portrait was painted, in 1777, a marble herm was discovered, a sculpted head and torso on a pillar, that is believed to be a Roman copy of Aspasia’s funeral stele. This monument now stands in the Vatican, and because it is believed to be a copy of a sculpture made of her during her lifetime, it lays claim to being the most accurate portrayal of Aspasia. She appears expressionless, serene, and solemn, clearly beautiful but noble of bearing and not sexualized. Of course, we don’t know for certain if it is an accurate representation of her, since her original fifth-century funerary stele is lost. So the sculpture stands, like all the depictions of Aspasia in her contradictory biographical traditions, as a construct, a symbol or placeholder for a woman whose real character we cannot truly know, since she has been erased from history, leaving only these exaggerated echoes and reflections.

Marble portrait herm identified by an inscription as Aspasia, possibly copied from her grave.

Until next time, remember, there is a difference between being unknown or forgotten by history and being purposely marginalized and erased. For most women throughout history, including for Aspasia, their memory was never preserved unless it was in relation to a man. So consider this. We know Aspasia had a son with Pericles, but she may have had numerous daughters we simply don’t know of, and would never know of, unless a man decided to inscribe their names on his own gravestone.

Further Reading

Bicknell, Peter J. “AXIOCHOS ALKIBIADOU, ASPASIA AND ASPASIOS.” L’Antiquité Classique, vol. 51, 1982, pp. 240–50. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41652643.

Henry, Madeleine. Prisoner of History: Aspasia of Miletus and Her Biographical Tradition. Oxford University Press, 1995.

MacDonald, Brian R. “The Megarian Decree.” Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte, vol. 32, no. 4, 1983, pp. 385–410. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4435862.

Wohl, Victoria. “Comedy and Athenian Law.” The Cambridge Companion to Greek Comedy, edited by Martin Revermann, Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp. 322–335. Cambridge Core, www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/cambridge-companion-to-greek-comedy/comedy-and-athenian-law/40DE6B891BECD393E3DBE361010CB331.

Wolkow, B. M. “The Mind of a Bitch: Pandora’s Motive and Intent in the Erga.” Hermes, vol. 135, no. 3, 2007, pp. 247–62. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40379125.