The Specter of Devil Worship, Part Two

In this installment, we’ll be discussing a subject that requires an examination of the details of alleged violent crimes against children. Reader be warned.

Welcome to part two and the conclusion of our Halloween edition of Historical Blindness. When we left off, we had just examined the accusations of black sabbaths performed by witches and warlocks and considered the evidence that witchcraft as the worship of the devil was only a mad construction of the Catholic Church and its Inquisition, growing out of previous allegations made to demonize heretics. Our final thought pondered whether any of these accusations had ever been grounded in fact.

Indeed, there appear to have been some accused of witchcraft who genuinely had been practicing sorcery, or at least attempting to do so. However, where there was genuine interest in magic and its practice (insofar as magic can actually be practiced), it was not of a Satanic aspect. At this time, Arabic texts on performing magic, and specifically summoning and controlling spirits, were being translated and found a readership in the West, but far from Satanic, these grimoires originated in pagan traditions and were simply adapted by Christians seeking to try their hand at magic. And even then, rather than being performed in deference to or worship of the devil, these magical ceremonies were usually meant to summon and bind a demon to serve one’s own purposes, usually to further some ambition through the control of others or to increase one’s wealth through some alchemical miracle. Take, for example, the story of Gilles de Rais, a French nobleman and war hero compatriot of Joan of Arc who during the Inquisition’s witch craze was executed for horrific crimes as well as for evoking and having discourse with the Devil.

Born into an established French family, Gilles de Rais inherited his title of Baron of Rais, as well as great wealth and extensive property. He was a brilliant young man, with a classical education in music, science, and Latin. After two betrothals that failed due to his fiancées suddenly dying, he was married by the age of 16, and by 25 he served with distinction as the Marshal of France. He was a Christian hero, serving alongside the Maid of Orleans in bringing aid to that city and marching on both Reims and Paris, though after he died in infamy, some have tried to expunge him from French history. This may be understandable when one considers the charges for which Gilles de Rais was executed.

Portrait of Gille de Rais, via Wikimedia Commons

After the glory days of Gilles de Rais’s military career, he became profligate with his wealth, employing far too many servants, raising his own standing military forces with funds out of his own pocket, and staging expensive dramatic productions. Before long, he had squandered his fortune and sought the help of alchemists to renew it. Along with the promise of transmuting base metals into gold, however, alchemists at the time were recognized as necromancers as well by the Catholic Church, casting spells and summoning demons in order to receive their favors. Gilles de Rais, therefore, began to seek more than just regaining his wealth in his pursuit of the alchemists’ philosopher’s stone. Having seen for himself in the person of Joan of Arc how supernatural power might be wielded by those in whom it is invested, he was led to believe that perhaps the alchemists he employed could endow him with powers of a god. After some failed attempts at summoning demons, it is said that eventually his alchemists succeeded in summoning the Devil himself, and in a contract Gilles de Rais signed in his own blood, he accepted a deal with the fiend. He would receive three rewards: science, power and wealth. In return, he need not surrender his soul. Instead, he needed only to burn five children and give their hearts to Satan.

And it would seem that Gilles de Rais took to his task with relish, or that perhaps he had already indulged in the horrific pastime of child murder. Whether innocent or already guilty of such crimes before his alchemical and diabolical quest, the evidence recorded after his eventual arrest suggests that between 1432 and 1440, he murdered more than 800 children, immolating them, amputating their limbs, severing their heads, scooping out their eyes and digging the hearts out of their chests as offerings to the Devil. These children were kidnapped and delivered to him by hired abductors, who later testified to their involvement. And as his various estates and castles fell into the hands of other family members, he enlisted other hirelings to help him hide his crimes by destroying the remains of children hidden there, a task which they also would testify to completing on his behalf. And finally, Gilles de Rais himself would confess to his crimes, offering from his own mouth the estimation that he murdered and sacrificed approximately 120 little boys every year for seven long and horrifying years.

Here, certainly, it would seem, we have evidence of human sacrifice to the Devil confirmed by the findings of a court. However, let us look more closely and with an open mind. Just as before many hangers-on were only too happy to help him squander his money, as he sought help in replenishing his coffers through alchemy, there was no shortage of confidence men posing as alchemists seeking to further relieve him of the last few coins he had. And if indeed he had not engaged in child murder before his alchemical pursuits, a notion supported by the further alleged detail that he always sought to save his own soul by praying to God for forgiveness both during and after his crimes, then surely the various alchemists who encouraged him to offer these sacrifices and convinced him they were necessary were the ones truly at fault, or at least they should share the blame for these heinous crimes, if they actually occurred.

Depiction of de Rais about his murderous sorcery, via Wikimedia Commons

And if these murders actually did occur, were they indeed made as offerings to Satan? If Gilles de Rais were actually a serial murderer, as some have claimed, perhaps driven by some sexual compulsion as indicated by the victimology of always targeting young boys, does this necessarily equate to devil worship? And if, instead, he only murdered these children in order to complete these arcane rituals, were they actually Satanic? As previously established, grimoires disseminating the traditions of alchemy and ceremonies for summoning demonic beings were not inherently Satanic in the sense that they derived from pagan traditions. And even a cursory examination of the ceremonies supposedly performed with Gilles de Rais shows that there was a lack of Satanic trappings. They involved circles drawn on the floor, not black candles and upside down crosses. While some accusations were made against him of performing Black Masses, these have proven unsubstantiated.

And as for the rest of the allegations, these too appear to lack credibility when examined closely. Gilles de Rais was tried by the Inquisition, and it has been pointed out that although he had squandered much of his wealth, he still retained a massive estate in the form of castles and other physical assets that the Church and his accusers were only too happy to seize upon their forfeiture. Indeed, Gilles de Rais confessed to his crimes… but not at first. Rather, he denied them and only admitted them after three days of torture. And while we do have the testimony of his accomplices, it is also possible that they were tortured themselves, as the Inquisitors were known to torture even witnesses! For anything resembling reliable evidence, then, we must look to the physical evidence, which also is lacking here. There is no unassailable record of investigators or other officials finding bodies, but rather only witness testimony of the destruction of said corpses, which testimony may have been coerced in order to explain why there was no evidence of bodies! Even reports of missing children during that period don’t offer any corroboration, as they don’t come near the number of murders alleged and can easily be explained without resorting to blaming a Satan-worshipping nobleman and his kidnapping ring.

Therefore, yet again, accusations of human sacrifice and Devil worship break down before reasonable examination. One begins to doubt, then, that there was ever any truth to these Satanic Panics. There is, however, more to come, and indeed, the next entry in our history of Devil worship should give one pause.

In 1678, French occultism showed its pale and horrible underbelly to the light in a scandal that has been called the Chambre Ardent Affair and the Affair of the Poisons. And here at the heart of what is otherwise a murder scandal, we finally find what appears to have been a verified case of ceremonies involving the offering of children for the conjuring of demonic forces. It all started when a lawyer at a dinner party overheard a high society fortune-teller bragging about providing “inheritance powder” to people in high places, this being a euphemism for poison. As poisoning was suspected of being rampant among noblemen and their wives, the lawyer reported the incident, and police investigated, uncovering a network of fortune-tellers whose real business was selling poison and performing abortions. As the investigation drew on, however, it would uncover more than abortion and the abetment of murder and would indeed touch far too close for the comfort of King Louis XIV. Thus he drew a veil of secrecy over the whole affair, choosing to prosecute the case in a Chambre Ardent, or Burning Chamber, called such because it was entirely closed off to the light of day and lit by torches, and perhaps also because, historically, such courts had been reserved for trying heretics, and their interiors had occasionally been lit by other kinds of burnings.

As the investigation unfolded, witnesses implicated further conspirators in the Affair of the Poisons, who in turn accused other and the layers of this criminal organization were peeled back. Eventually, officials came to the heart of the matter. At the center of this network was Catherine Monvoisin, better known as La Voisin, who was known to burn the fetuses she aborted in a secret furnace beneath her house. Moreover, it came forth that she had raised an unusual pavilion on the grounds of her house as a kind of chapel. In this unhallowed place, she arranged for profane rituals to take place, hiring an old priest named Abbé Guibourg to perform them. These rituals were evocations, conjuring demons and offering sacrifice to them in return for favors. The investigation came reached all the way to the king when his mistress, Madame de Montespan, was implicated as having availed herself of these ceremonies in an effort to keep the king’s affections.

Portrait of La Voisin, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the Burning Chamber, in a reversal of ordinary procedures, the priest Abbé Guibourg gave his confession to a secular authority, and what he revealed struck everyone with horror. Abbé Guibourg said his twisted version of a mass on the belly of a nude woman, treating her as an altar. At the appointed time of the mass, a baby was presented to him, whose blood he shed by cutting its innocent throat. This child’s blood he poured into a chalice, calling to the demonic entities Astaroth and Asmodee to accept this sacrifice in exchange for meeting his demand, which was that Madame Montespan, present there with only a veil over her head and bosom, would continue to enjoy the amity of the king and that he would deny her nothing.

After the baby, thus drained of its blood, was taken away, its viscera and heart were carried back to the dark priest, who then ground them up for Montespan to consume as well as to slip secretly to the king. Her demand were written as follows:

…I demand the love of the King…and that the Queen shall be sterile, and the King shall leave her bed and her table for me, that I shall obtain all that I ask for me and my parents…that I shall be called to the counsels of the King, and to know what happens there…and that the Queen shall be repudiated, that I shall be able to marry the King.

The King’s mistress was never tried for her participation in these terrible rituals, but Abbé Guibourg was imprisoned for the rest of his life, along with a great many others who were involved in the Affair of the Poisons, while others were put to death, including La Voison, the woman at the head of this Satanic network, who was burned at the stake. source:

Although torture was, again, a factor in the proceedings of this Burning Chamber, the fact that the awful details of these terrible rituals were corroborated by multiple witnesses tends to lend Guibourg’s testimony credence. However, it should be noted that the babies described as being sacrificed were already dead. Providing illegal abortion services to women across Paris, La Voisin had a plentiful supply of fetuses at her disposal, so it appears that, rather than live sacrifices to dark powers, these were something more like grisly props in a disgusting theatrical production. Perhaps this is cold comfort, but again we see the specter of true devil worship becoming more and more ethereal with closer examination.

For example, the story appears at first glance to be a confirmed and proven instance of devil worship, or at least of diabolical deal-making, but consider the demons to which the priest appealed: Asmodee and Astaroth. They appear to be appropriate entities for the occasion, the former being thought to inspire lust and lechery in men and the latter known to grant friendships with great lords, but follow their history farther back and we find these figures do not even originate from Christian or even Hebrew traditions but rather from other religions, such as Zoroastrianism, and both appear to be derived from Astarte or Ishtar, a fertility goddess of Phoenician and Persian mythology. The idea that some unscrupulous priest would pretend to hold such a ceremony, drawing from centuries of lore made available in grimoire literature and thereafter promulgated by the Catholic Church and its Inquisitors, who spread everywhere the idea of such rituals existing, certainly doesn’t stretch the imagination, especially when one remembers that Abbé Guibourg was accepting payment for performing these rituals, which despite the horrendous element of using aborted fetuses as props, seem rather ridiculous in this light.

La Voison and Abbé Guibourg's Black Mass performed on Madame de Montespan, via Wikimedia Commons

Guibourg’s rituals would themselves help to mold the legend, thus perpetuating the cycle, with myth inspiring real practice that went on to fuel the myth, as thereafter reports of Black Masses, rituals parodying and profaning the Catholic Mass, most of them reflecting elements of Guibourg’s rituals with nude women as altars and the sacrifice and consumption of babies, proliferated in 18th and 19th century Europe.

One group accused of engaging in such ceremonies were the Hell-Fire Clubs of 18th century London, who have been said to hold full-fledged Satanic rituals, with black candles and inverted crucifixes, orgies in which forbidden sex of all kinds—even incest—was indulged, and, familiarly, the conjuration of the devil himself in the form of a goat or a cat. History shows, however, that the Hell-Fire Club was little more than a drinking club and themed society like the Freemasons originally formed to liven up otherwise boring and prudish Sundays with some carousing. The group took its inspiration from Rabelais’s satirical work Gargantua and the fictional monks at Thelème, whose motto was “Do what thou wilt,” a philosophy that would later influence occultists in the 20th century, who in their own turn would be called Satanists and even embrace the label, foremost of these being Aleister Crowley, but we may leave that colorful figure for another episode. It is enough here to say that The Hell-Fire Club has been rather inaccurately remembered and unfairly maligned. In reality, nothing more nefarious went on there than might be expected to occur inside the windowless rooms of your local Masonic temple.

But indeed, what might go on within those secretive enclaves? Much has been made of a nebulous and secret connection between the Masonic fraternity and the Knights Templar, suggesting that the latter actually survived their extermination by hiding among the ranks of the former and incorporating their traditions and rituals into those of the Freemasons. So then, of course, if the Templars were secretly Satanists, might not the Masons who received them and protected them be devil worshippers as well? In the 19th century, an era that saw much anti-Masonic sentiment, there arose evidence that, indeed, the Satanic Masonic conspiracy was real and more widespread than any might have imagined.

In 1885, a writer best known by the pen name Léo Taxil, who had previously been a major critic of the Catholic Church, gave up his secular crusade against them and converted to the faith very publicly. Now firmly on the Church’s side, he began to aim his pen and his sharp words at the enemies of the Pope, foremost of which was the Masonic fraternity, which Pope Leo XIII had condemned for its religious tolerance. During the course of Taxil’s crusade against Freemasonry, he claimed to have uncovered a secret Gnostic tradition, suggesting that the Masons worshiped the devil, Lucifer, as the true and misunderstood god of light, and despised Adonai, the god of the bible, as a false and cruel deity. He revealed in his writings that for many years, the original Baphomet idol of the Knights Templar had resided at the Masonic Temple in Charleston, South Carolina, the seat of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, where the Grand Master of its Supreme Council, Albert Pike—a military figure of the Mexican-American War as well as the Civil War on the side of the Confederacy, whose statue stands today in Washington, D.C.—was inspired to establish a secret Luciferian branch of Masonry there call the Reformed Palladium. The Palladists, unknown to much of the rank and file of everyday Masons, performed grotesque Luciferian rituals, which included sexual debauchery, for unlike most of Freemasonry, the Palladian Rite secretly initiated women into its ranks.

Masonic devil worship, as alleged by Léo Taxil, complete with Templar costumes and Baphomet idol, via Freemason Information

Soon it was not Taxil alone alleging these things, as in an 1891 pamphlet, one Adolphe Ricoux published what he claimed were the theological writings of Albert Pike himself , explicating the notion that there were two gods, Adonai and Lucifer, and the Palladist Freemasons were rightly to be called Luciferians, as Satanists accepted the theology of Christianity but chose to worship evil instead of good while Luciferians rejected the entire paradigm, claiming it to be lies spread by Adonai, god of evil and darkness.

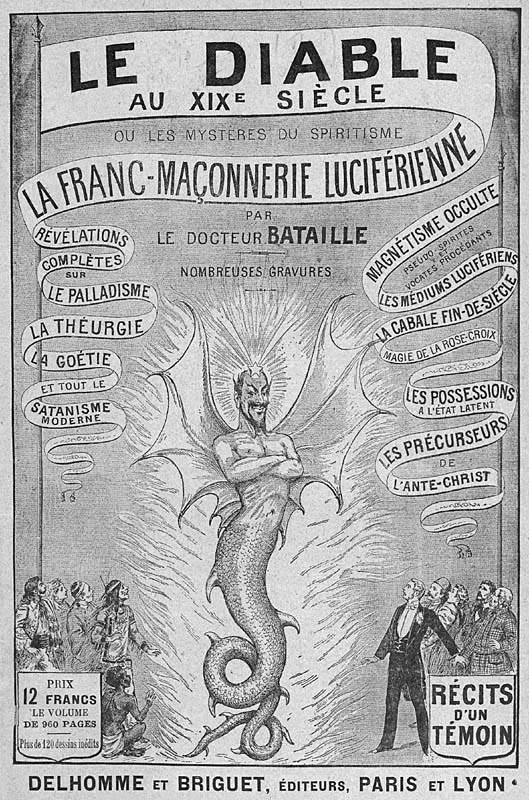

Perhaps the most frightening exposé of Palladian Freemasonry’s devil worship came the next year, when a huge serial publication called The Devil in the 19th Century was printed and disseminated. In it, one Dr. Bataille told the extraordinary story of his infiltration of the evil Palladists.

Serving as a ship’s surgeon aboard the steamboat Anadyr in 1880, Dr. Bataille had occasion to befired an Italian silk merchant named Gaëtano Carbuccia healthy and ribald atheist who during the course of his journeys appeared to transform before Bataille’s eyes into a forlorn and feeble old man. Investigating, Bataille coaxed from Carbuccia his story of becoming involved in the Palladian Rite of Freemasonry, where during one ceremony, he witnessed a séance at the altar of Baphomet over the skulls of fallen missionaries at which the shining figure of Lucifer appeared in corporeal form. Believing himself damned for his participation, he had lost all hope in redemption.

Obsessed with this story, Dr. Bataille embarked on a journey of his own that would lead him around the world and into the very heart of a palpable darkness. In Naples, he bought his way into the Masonic brotherhood, and he began his infiltration in what today is called Sri Lanka, where having insinuated himself among the Palladists there, he was taken to a hut to give his medical opinion on a bedridden woman, whom he assured them was wasted away to near death, if she was not dead already. Promptly, then, the woman suddenly rose, crawled to an altar beneath the figure of Baphomet, and allowed herself to be burned alive by the chanting devil worshipers.

Thereafter, having still not learned enough of these Palladists and their horrors, Bataille went to India, to a French colonial settlement, where once again penetrating the inner circle of Luciferian activity there, he visited a temple where worshipers surrounding Baphomet’s statue had allowed themselves to waste away until they were rotting, like living corpses supplicating themselves before the idol, their flesh ulcerating and gangrenous, faces eaten by rats. One of them tried to call out to Beelzebub, but each time he tried to speak, his eye, which hung out of its socket, fell into his mouth. When no devil was conjured, a woman was brought out and cheerfully burned her arm in hot coals. This also not successfully evoking Lucifer, they moved on to a gruesome sacrifice of a goat, and then to cutting the throat of one of the putrefying supplicants as a human sacrifice. All of the rituals failed in their object of conjuring the devil, but they succeeded in leaving Dr. Bataille sick for days.

Cover illustration of "The Devil in the XIX Century," via Wikimedia Commons

Eventually, the doctor arrived at Calcutta, where he was conducted to a mountain atop which seven temples had been built. In each of these temples, he saw countless horrors, such as baptism into a pit of writhing venomous snakes, the sacrifice of numerous animals, the spontaneous levitation and disappearance of devil worshipers, and a final ceremony in a charnel house where participants made their incantations while lying in the cold embrace of decomposing corpses.

The good doctor continued on his dark journey of initiation into Palladism, going next to Singapore, then China, and finally to the Great City of Lucifer, the Rome of Satan, Charleston, South Carolina. During the course of his infiltration, Dr. Bataille came to learn of two women who represented a struggle for the heart of Palladism. One was Sophia Walder, chief of the female order, and the other was a newcomer, Diana Vaughan. Sophia was said to keep a serpent familiar and to wield great supernatural power, having the ability of substitution, to be able to transform herself at will into other, often well-known figures. Diana also was known to levitate and bilocate, or be in more than one place at a time, and on some occasions when the demon Asmodeus was successfully conjured, he made it clear that he favored Diana and would eventually take her as his wife. The rift between these two women split the Reformed Palladium, until, like Leo Taxil himself, Diana Vaughan saw the error of her ways and converted to Catholicism. In an effort to make amends for her Satanic activity, she began to publish a serialized exposé of her own entitled Memoirs of an Ex-Palladist.

The wealth of testimony being published by Léo Taxil and others caused a resurgent Satanic Panic and Anti-Masonic movement at the end of the 19th century, such that Taxil even had an audience with and support from Pope Leo XIII. After Diana Vaughan’s conversion and the publication of her memoirs had begun, many in the press demanded to interview her, and in 1897, Léo Taxil arranged a press conference at the Geographical Society, promising that Diana Vaughan would finally present herself to the public. At the appointed time, Taxil spoke to the gathered crowd… and explained that he had perpetrated one of the greatest hoaxes in modern history. Not only was Diana Vaughan an invention of his, but so was Dr. Bataille and Adolphe Ricoux and all of the awful details about the Reformed Palladium, which he had fabricated. Even his conversion to Catholicism had been part of the hoax, which was all calculated to make a fool of the Pope and the Catholic Church. Calling it a “joyous obfuscation,” he predicted that it would be met with “a universal roar of laughter.” “Palladism,” he said, “my most beautiful creation, never existed except on paper and in thousands of minds! It will never return!”

Léo Taxil, looking rather pleased with himself, via MasonicDictionary.com

But of course it did, though perhaps not under the same name. Not even a hundred year later, the Satanic Panic in America had people believing again in secret cemetery conclaves and far-reaching diabolical conspiracies. This is the nature of historical blindness. When blind spots persist in our past, and when we turn a blind eye to the lessons to be learned there, we fall into the most foolish of patterns and repeat some of the most shameful passages in history. To quote a writer who himself was considered a Satanist, “The Devil’s best trick is to convince us that he does not exist.” On the contrary, considering the death and suffering that resulted from accusations of witchcraft and devil worship throughout history, it would seem his greatest victory was in convincing the world that he did exist.