Blind Spot: Charles Dellschau and His Extraordinary Sonora Aero Club

In the last edition, I surveyed the history of innovation in ballooning before telling the tale of the mysterious sightings that occurred in 1896 and ’97, but is it possible that there is a further history of aviation pioneering that didn’t make it into the historical record? Could some inventors have made great strides in the design and building of airships? If fleets of flying machines really were seen in 1896 and 1897, then it would seem someone must have. And there does exist a body of work that claims to answer these questions. In all, it comprises some 2000 pages, with watercolor paintings and handmade collages as well as handwritten passages that purport to reveal the existence of an organization of airship inventors who made great advances in aviation in the 1850s, but did so entirely in secret. But is this a work of history or a work of art? Does it impart fact or simply weave an intriguing fiction?

The work began around the turn of the 20th century. The artist was then a man of around 70 years, a Prussian immigrant by the name of Charles Albert August Dellschau who had arrived at Galveston in 1849 at the age of 19. He lived much of his life in Texas, working in Richmond as a butcher, as had been his father’s trade. In 1861, he married a widow with a 5 year old girl. Decades later, after losing his wife and most of the children he had fathered with her, he moved from Richmond to Houston to work as a clerk for his step-daughter’s husband, a saddler maker. In the mid-1890s, his son-in-law also passed away, and Dellschau moved in with his widowed step-daughter and her several children. He retired right around when the airship flaps began. Not long after these incredible sightings of flying ships, Charles Dellschau, who seems to have spent most of his time in his step-daughter’s attic, began to write his illustrated memoirs. This undertaking thereafter turned into a seemingly endless series of drawings, paintings, and collages on butcher paper. It seems he produced one new intricate work of art of this sort about every two days, working by candle light up in his attic studio, until he died in 1923 at the age of 93. He never tried to publish his writings or sell his artwork in life, and after he was gone, his family left it moldering up in that attic until the 1960s, when a house fire prompted a fire inspector to clean out the attic. Thinking all the old papers a fire hazard, he dumped them all on the curb. Somehow, the artwork thereafter came into the possession of the owner of a local store, where for even longer it remained hidden under various other items—tarps and carpets—until its rediscovery and sale to various art galleries and museums, and to a researcher named P. J. Navarro, whose interest lay principally in the mystery airship sightings of the late 1890s. From there, the work of Charles Dellschau entered history and the public consciousness.

A manuscript of Charles Dellschau’s work, via Wikimedia Commons

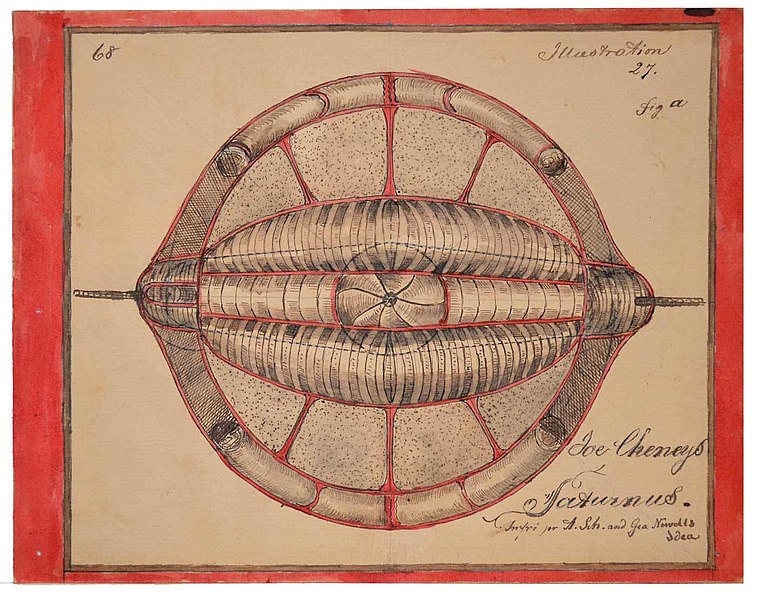

You see, rather than the simple autobiography of a butcher, as one might have expected from him, his writings and his illustrations and collages depicted in vivid detail his involvement with a society of airship makers in California. If Dellschau’s work is to be believed, then sometime in the early to mid-1850s, not long after he first arrived in Texas, he traveled to California, to the gold rush country west of Yosemite, where in a small town called Sonora, he served as the draftsman for a secret society of airship builders. This group, the Sonora Aero Club, was composed of men with Germanic names, likely immigrants to America just like Dellschau, and they met among miners in the saloon at Sonora, talking not of gold but of flight. One man in particular stands out in Dellschau’s works as the leader or principal innovator in the Sonora Aero Club: one Peter Mennis. A German miner and rough sort, he is described as a drunk and a genius, tinkering with airships for the sole purpose of astonishing friends and maybe making enough money to keep himself in drink. It is he who engineers or discovers the miraculous “Lifting Fluid” that eventually allows all the Sonora Aero Club’s ships to float and fly. Mennis calls this material “Supe.” Essentially, it replaced hydrogen in their designs, as drops of it, released onto rotating metal plates called an “Electrande,” resulted in a gas that filled the airships’ envelopes to provide lift. So you might say they were driving around souped-up hot-air balloons. From his memoirs, one gets the impression that the club is a group of jovial aviation enthusiasts, keenly interested in the mechanics of flight, yes, but perhaps even more interested in telling a good tale and having a raucous good time at the local tavern.

Example of Dellschau’s work, via Wikimedia Commons

But there is mystery and intrigue in Dellschau’s club as well, for theirs was a secret society, and their undertakings performed under a strict code of silence. In one margin, among the many tales told in scrawled annotations on his paintings, he tells of an airship pilot that the club suspected was taking payment for transporting cargo, and how the club orchestrated the crash of his vessel in retaliation. There is mention of members being forbidden to build the ships they had designed because they had been sharing too much information with people outside the club, and of a nosy boardinghouse owner who tried to eavesdrop on their meetings and got stranded on a cliff for her snooping. When ships were built, they had to be disguised as wagons so that no one who saw them would think anything of them. Indeed, even a half a century later, Dellschau didn’t seem entirely comfortable writing about the secrets of the Aero Club, so some of his work is written in code, which of course is very odd for a memoir or a history. Some details that we have come from the researcher P. J. Navarro, who claims to have cracked Dellschau’s code after years of studying his work. Acccording to Navarro, one prominent coded phrase, seemingly in Greek characters, ĐM = XØ (delta mu = chi phi) represents the name of a mysterious organization that financed or somehow otherwise supported or made possible the innovations of the Sonora Aero Club. Navarro says this phrase decodes to NYMZA, although no one really knows what that acronym might stand for. Other researchers suggest that these coded portions were only responses to the Great War in Europe that Dellschau introduced after 1914, as though he had to keep things secret in a time of war, and judging from context, they seem to just be a code for the name of the club itself. But that hasn’t stopped the shadowy NYMZA from becoming a dark and looming entity that casts its shadow over the entire legend, a development we will explore shortly.

An example of Dellschau’s work, via Wikimedia Commons

As Dellschau tells it, this was a golden era of aviation in the deep gold country of California. Members of the club held forth about their designs in their secret meetings behind their boardinghouse. They traveled the roads in airships disguised as covered wagons waiting until no one was around so they could take flight and go on extended voyages through the skies, sleeping and eating their meals high up in the clouds. But as with all good things, the club eventually came to an end. Crashes are not uncommon in his stories about the club, a fact which really lends his tales authenticity or verisimilitude. For example, one story tells of an aero being commandeered by a pilot who was not up to the task and drove the ship right into a redwood and broke his neck. For the most part, though, the club easily recovered from such accidents. But when, in the 1860s, Peter Mennis himself died in a fiery crash, the secret of his Lifting Fluid died with him. Apparently the Club floundered for some time, trying to recreate Mennis’s miraculous substance, but in the end, club members went their separate ways, like Dellschau, who ended up back in Texas, if you believe his stories, content to marry and work for 26 years as a butcher after all the profound adventures he had experienced. Now some would argue that this was not the end of the Aero Club, and would suggest that after thirty to forty years of experimentation, former members must have finally perfected the Supe, resulting in the appearance of all those many airships in the 1890s. And these believers will likely point to some recognizable names in Dellschau’s work, suggesting that a Smith that Dellschau mentions must be the same Smith that patented an airship design in 1896, or that a Wilson he refers to is likely the same Wilson mentioned in a series of Texas airship sightings, but these are common names being linked to persons decades and many miles apart. There is only one concrete piece of evidence remaining that the Aero Club existed, and it is the artwork of Charles A. A. Dellschau, which cannot be taken as definitive proof.

An example of Dellschau’s work, via Wikimedia Commons

Of course, this has not kept conspiracy theorists and fringe thinkers from doing what they do best, and now the Sonora Aero Club is all tied up in a variety of outlandish ideas with little basis in fact. Take the books and articles of Walter Bosley for an example. Bosley claims that, not only was the Aero Club real, but that the reason why their technology never went mainstream, so to speak, and simply disappeared after the airship sightings, was that this represented the beginning of a breakaway civilization. If you are unfamiliar with idea of breakaway civilizations, think about bad sci-fi in which Nazis developed advanced technology and then withdrew from the world to start their own society in Antarctica, or within the hollow earth, or on the moon. It’s wild stuff, and Bosley doesn’t hesitate to draw connections between the Aero Club and its financiers, NYMZA, and the Nazis with their rumored experimental aircraft, the Nazi Bell. In fact, drawing connecting lines is what Bosley does, even when there are no dots to connect. He suggests that in 1903, when the Wright Brothers were struggling to get their plane off the ground, a rumored airship flight to Mars actually did take place using technology from Nicola Tesla, and that this represents the beginning of another breakaway group. What’s more than that, he even manages to bring Donald Trump into the conspiracy, pointing out that one Dellschau painting has the name Homer Trump below a particular ship, suggesting that maybe one of Donald’s Trump’s relatives was part of the Aero Club, and further pointing out that Trump’s uncle, John G. Trump, was one of the FBI agents who went through Tesla’s documents after he died, hinting at some kind of cloak and dagger intrigue between these two rival breakaway civilizations. But even Walter Bosley himself seems to have embraced his critics’ biggest complaint against his theories and freely admits that he engages in “wild ass speculation.”

An example of Dellschau’s work, via Wikimedia Commons

The fact is, though, that elements of Dellschau’s story invite speculation as to its authenticity. It has been observed that the machinery he drew was very precise, and that he used the same mechanisms over and over again, which would likely be the case if inventors were building their designs on previous iterations. Does this just represent a lack of imagination on Dellschau’s part or is it a stroke of realism? It can hardly be said, when looking at his work, that he lacked imagination, and this may actually be a mark against the veracity of his stories, for many of the stories in his early memoirs are ridiculous, featuring a very fictive protagonist-antagonist relationship between Peter Mennis and an obese foil named Christian Axel von Roemeling who crashes his airship and thereafter becomes the butt of various pranks. Indeed, the simple fact that Dellschau purports to remember verbatim the words spoken so many years ago is itself suspect, like when he goes into some of Mennis’s speeches, such as when Mennis tells of a dream he has and it becomes a narrative about rescuing the corpulent Roemeling from the moon. And yet, when one wants to confirm that Dellschau wasn’t in Sonora in the 1850s, one finds a blind spot in his past. No one seems able to confirm his whereabouts between his arrival at Galveston in 1849 and his marriage in Richmond in 1861. But likewise, no one has been able to dig up any historical evidence of any of the principal characters ever having lived around Sonora at the time either. And even if this evidence were ever discovered, wouldn’t it be easier to believe that these were just some pranksters spouting off at a saloon, maybe something akin to the The Ancient and Honorable Order of E Clampus Vitus, that drinking club and parody of a fraternal organization called the Clampers, which was active in Sonora at the time and is known for its pranks and false mythology. And in the same way, isn’t it easier to believe that after the airship sighting hysteria, and during the decades of genuine aviation breakthroughs afterward, this old man undertook an ingenious art project, rather than that at twenty years of age, fresh in the country and with no experience doing anything other than carving meat, this young man was spirited away to California to serve as the draftsman for a secret society of balloonists with near-magical technology? Then again, I suppose, just because something is easier to believe doesn’t always make it true.

Further Reading

Charles A. A. Dellschau (monograph), edited by Stephen Romero, Marquand Books, 2013.